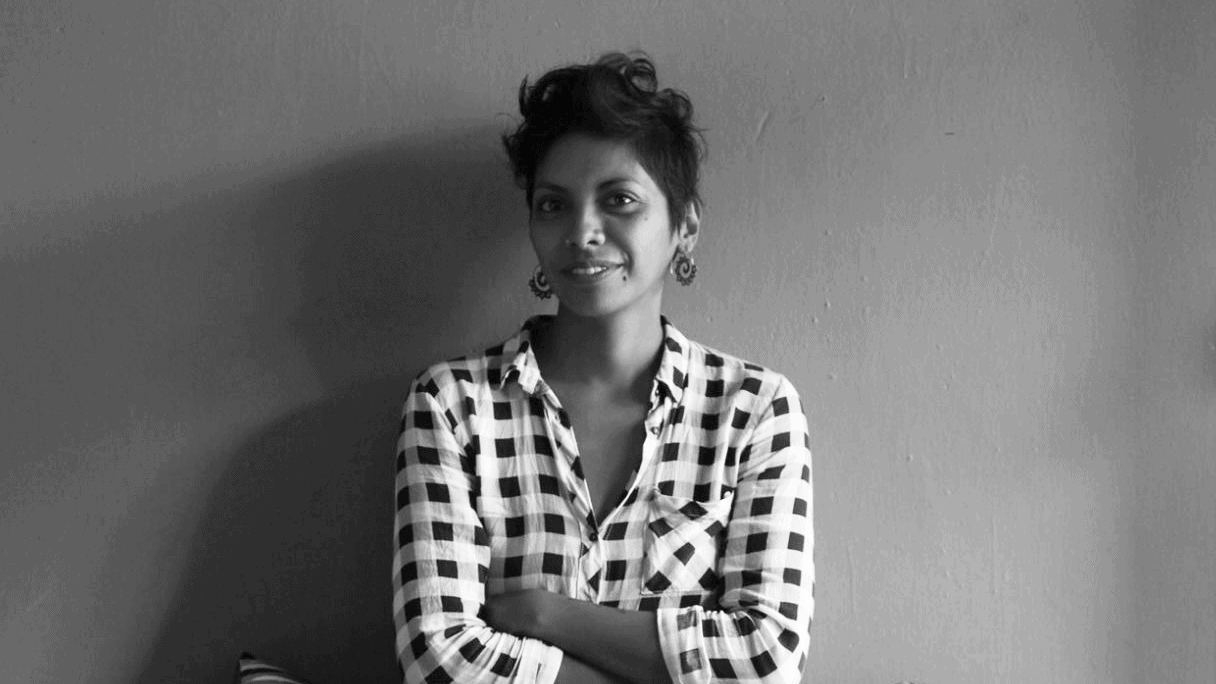

Kucha Suto

In 1713 the town known today as San Basilio de Palenque was founded in the mountainous area near Cartagena. A group of maroons led by Benkos Biohó founded the first free town in South America. Palenque, as it is commonly named, is an Afro-descendant town that preserves many cultural traditions of African origin. Its people developed a language known as Palenquero, the only Creole language in the Americas that combines a Spanish lexical base with the grammar of the Bantu languages.

In 1999, a group of teachers, concerned about the situation of weakness in which the Palenquero language was entering and interested in strengthening feelings of belonging, started Kucha Suto, which means “listen to us”. The initiative consisted of creating spaces within the school for students to speak in Palenquero and tell stories. They started with a radio, the students had the task of talking with their elders to tell stories on the broadcasts.

Soon after, they decided to take the station out of the school and put it on the main street of the town. At that time, says Rodolfo Palomino, one of the members of the process, “the station worked with the lungs”, as it consisted of a microphone and a speaker. People would come by and send greetings, leave messages, or dedicate songs.

In 2003, a group of displaced people from the village of La Bonga arrived near Palenque. They had received a pamphlet giving them 48 hours to leave the village. The members of Kucha Suto decided to move to where the newcomers were, knowing that they had a lot to tell. Rodolfo had barely entered to be part of the process when that happened. They collected stories that were recorded and written and that told not only what had happened in the displacement, but everything they had left behind.

Shortly after, and with the support of the Línea 21 collective that worked mainly in Los Montes de María, they got the necessary equipment to broadcast on air, they could record and have longer and continuous programmes. The group also supported the efforts to build the town’s cultural house, where they moved and where they currently have a space. From there, many of its members were able to train in audiovisual techniques, and not only did they tell stories on the radio, but they began to record videos and take photographs

The arrival of La Bonga people showed that the armed actors were closer than previously thought. The palenqueros were afraid, before dark the families locked themselves in their houses in fear of what could happen at night. Rodolfo says that this was very strange, and that then they decided to create a space for people to come together and meet again: traveling cinema.

On a screen they began to project images of what they were doing, “people like to see each other,” says Rodolfo. The exercise not only managed to reunite the inhabitants, but also began to function as a memory exercise.

The elders remembered people who had been in their territory photographing, interviewing or recording, but did not remember having seen the material they produced. The members of Kucha Suto decided to investigate, and as they found all the material produced, they began a process of “repatriation”. With all they found, they created an audiovisual archive, the cataloging of which goes through the members of the community who, when they see the pieces, remember what happened outside the frame.

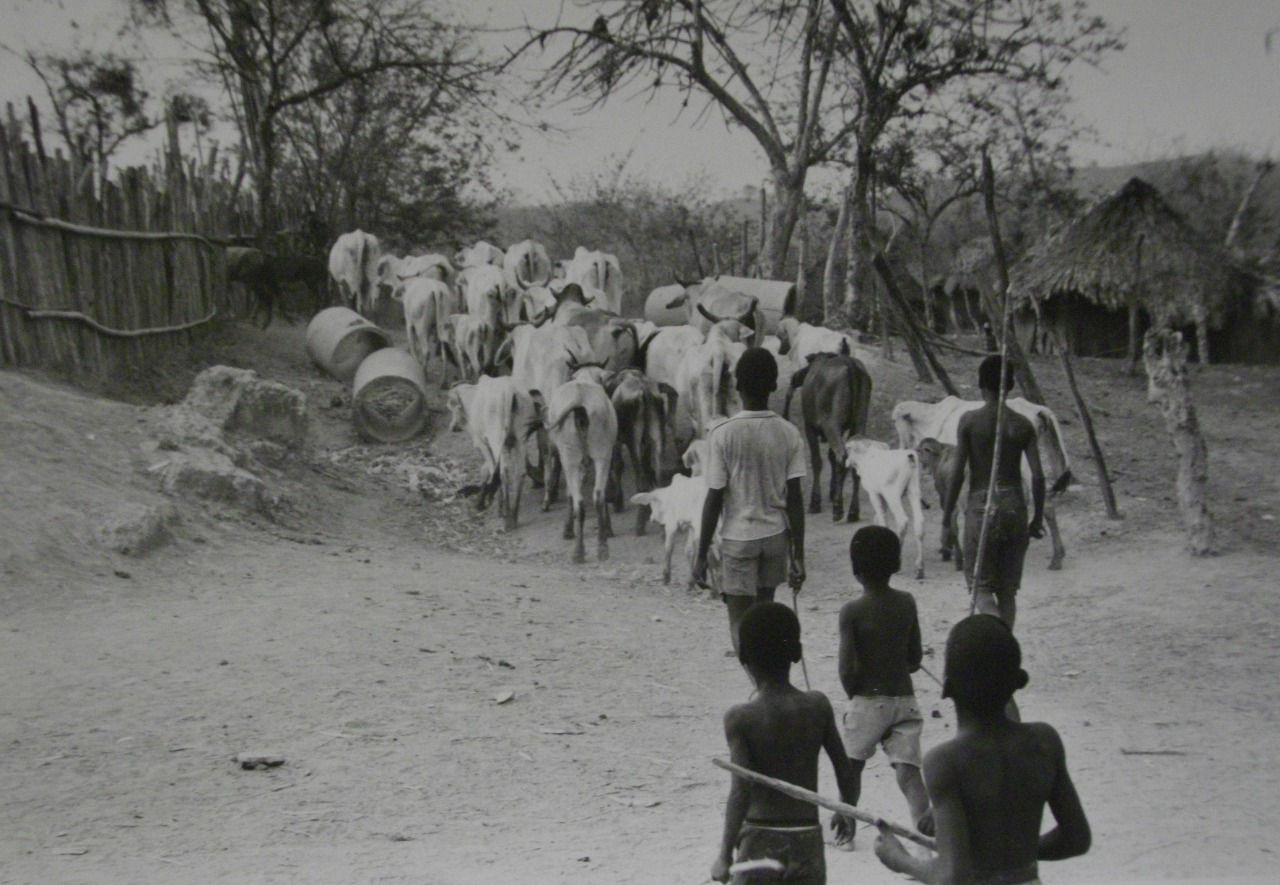

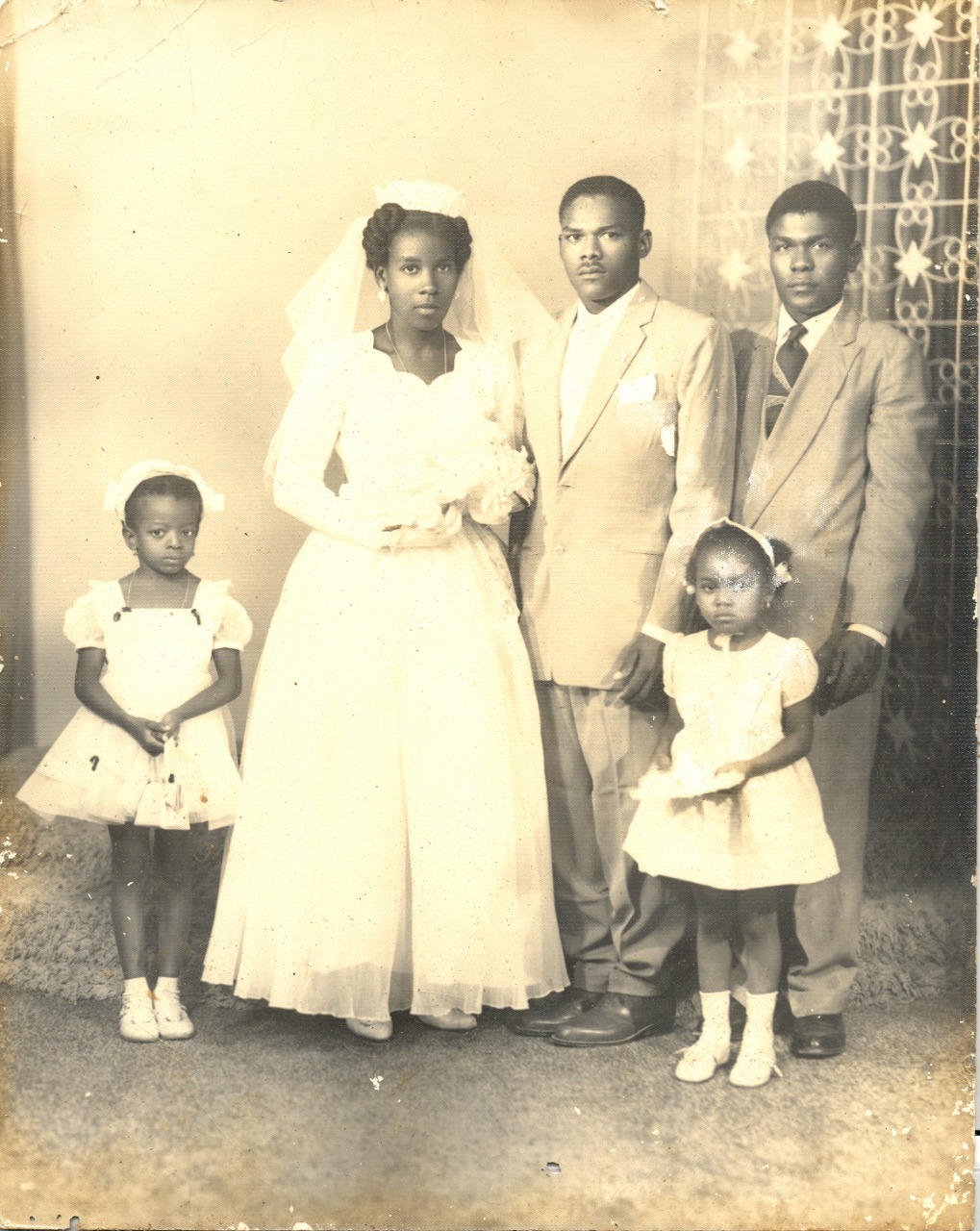

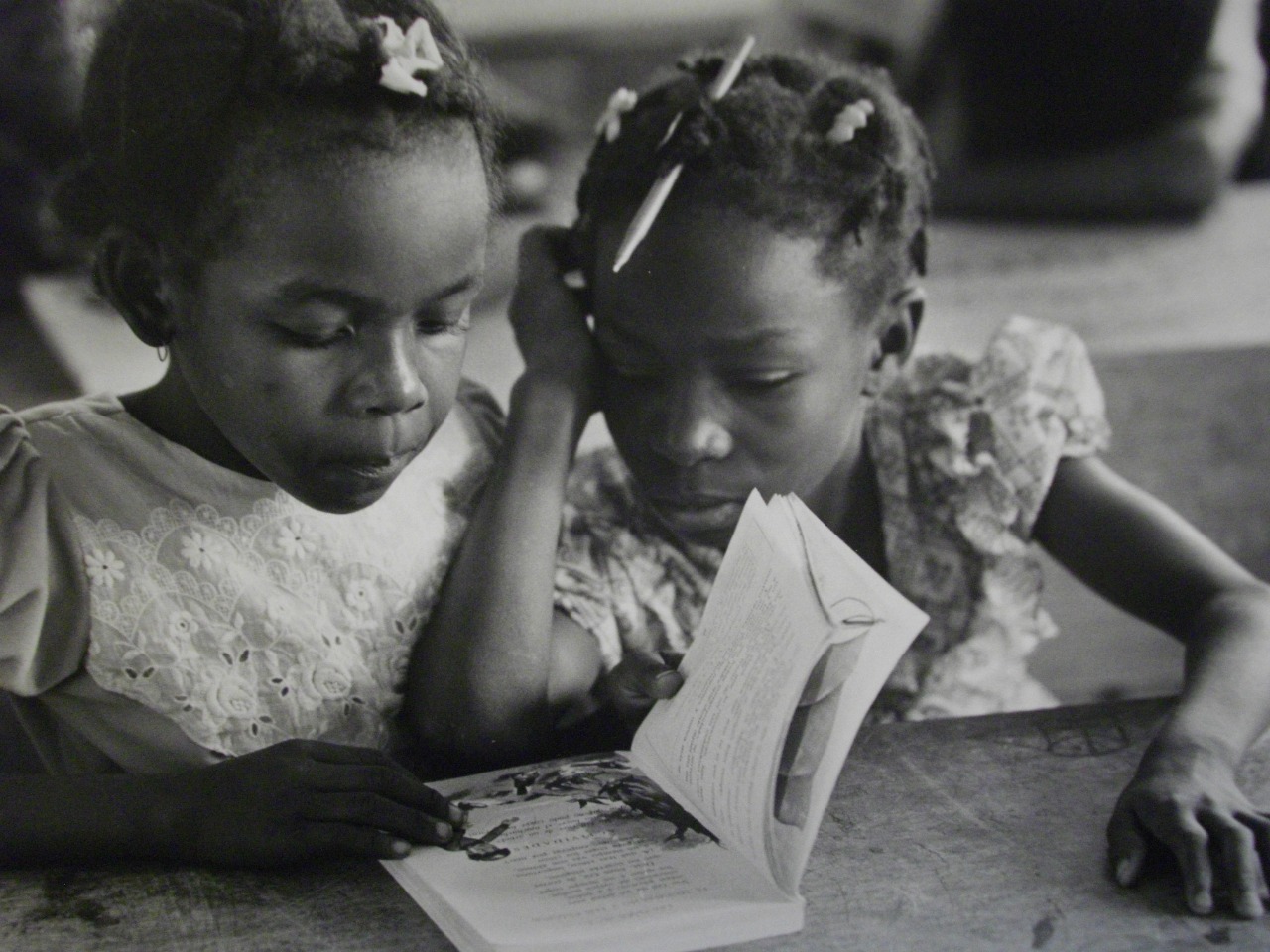

Nina S. de Friedeman documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto rights to use.

In 2013, Kucha Suto won an India Catalina award at the Cartagena de Indias International Film Festival, and from that moment on they feel that their practice is increasingly demanding and important. Currently, they have a recording studio where they have produced several albums of both traditional and other musical groups. They continue making audiovisual and communicative pieces and training to educate others in this process. All done “with identity”, respecting traditions, speaking in Palenquero and strengthening their culture.

Kucha Suto accompanied and supported the first of a series of workshops that VIST, in alliance with AECID, will be developing in Afro-descendant communities in different Latin American countries. The objective is to generate processes of training, creation and dialogues about oral memories using tools for the creation of images such as: storyboard, audio recording, photography and visual narratives. All this with the intention of keeping the collective memory alive.

Storyboard workshops – Vist Projects

Storyboard workshops – Vist Projects

How did Kucha Suto start?

Kucha Suto is a process that began at the Benkos Biohó educational institution in 1999 and began doing radio and to preserve and appropriate our own language, the Palenquero. The process began led by professors such as Sebastián Salgado Reyes from the area of the native language and Mari Dicimarro Espino, professor of Spanish language and art. The professor Zoila and around four teachers more began to speak the Palenque language.

At that time, the communication group Línea 21 de Montes de María appeared, and promoted the process led by the teachers and began to implement an accompaniment from the radio production itself. Radio content was produced in Palenquero language and it was heard through loudspeakers around the school and in all classrooms. Later, it became a community radio station, a station for the whole town, where everyone who passed by could stop and say something.

Since then, some colleagues who are now part of Kucha Suto were 8 or 9 years old. I joined Kucha Suto in 2003 after the population displaced by the armed conflict arrived about 15 kilometers from the town. At that moment, they decided to take the process out of school, to see how, through communication with alternative media, the memory of the displaced population could also be supported and told.

Nina S. de Friedeman documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto rights to use.

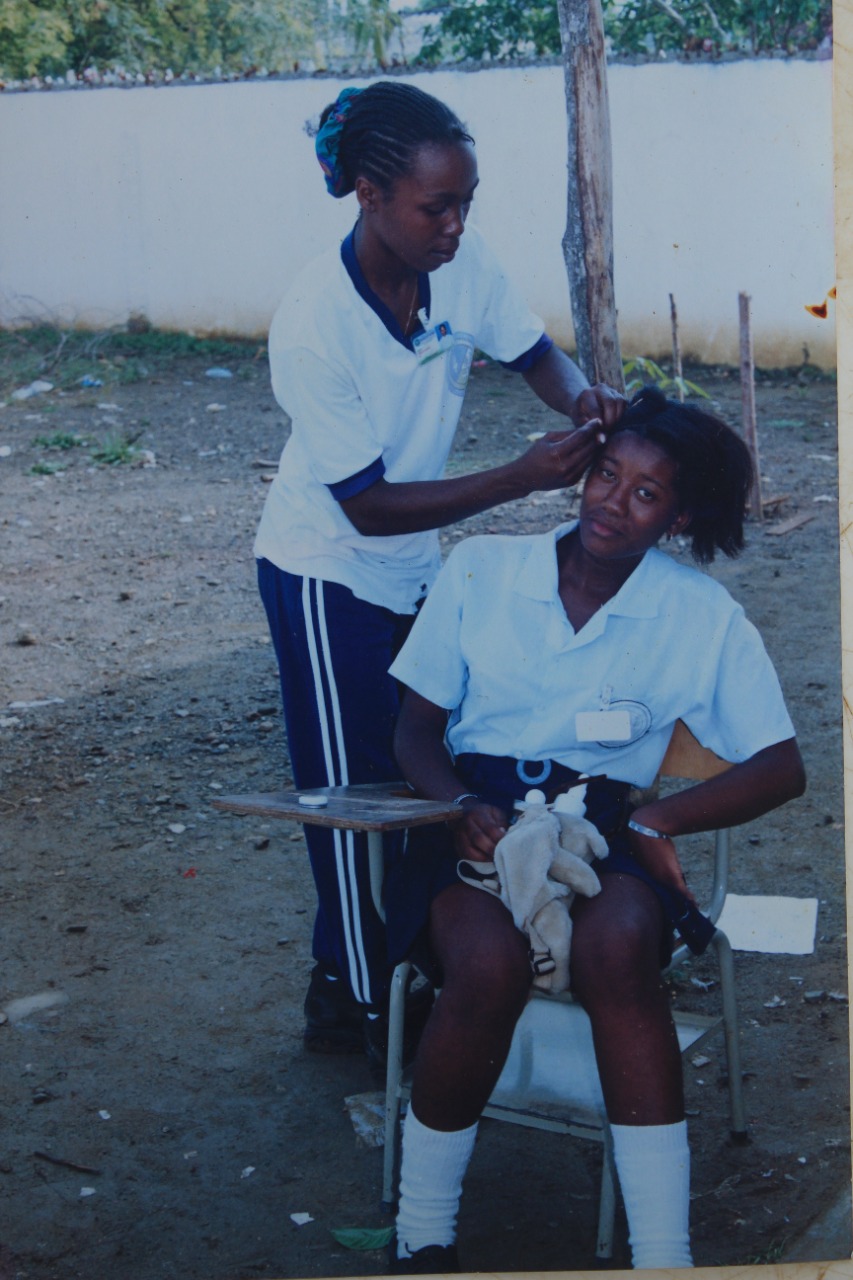

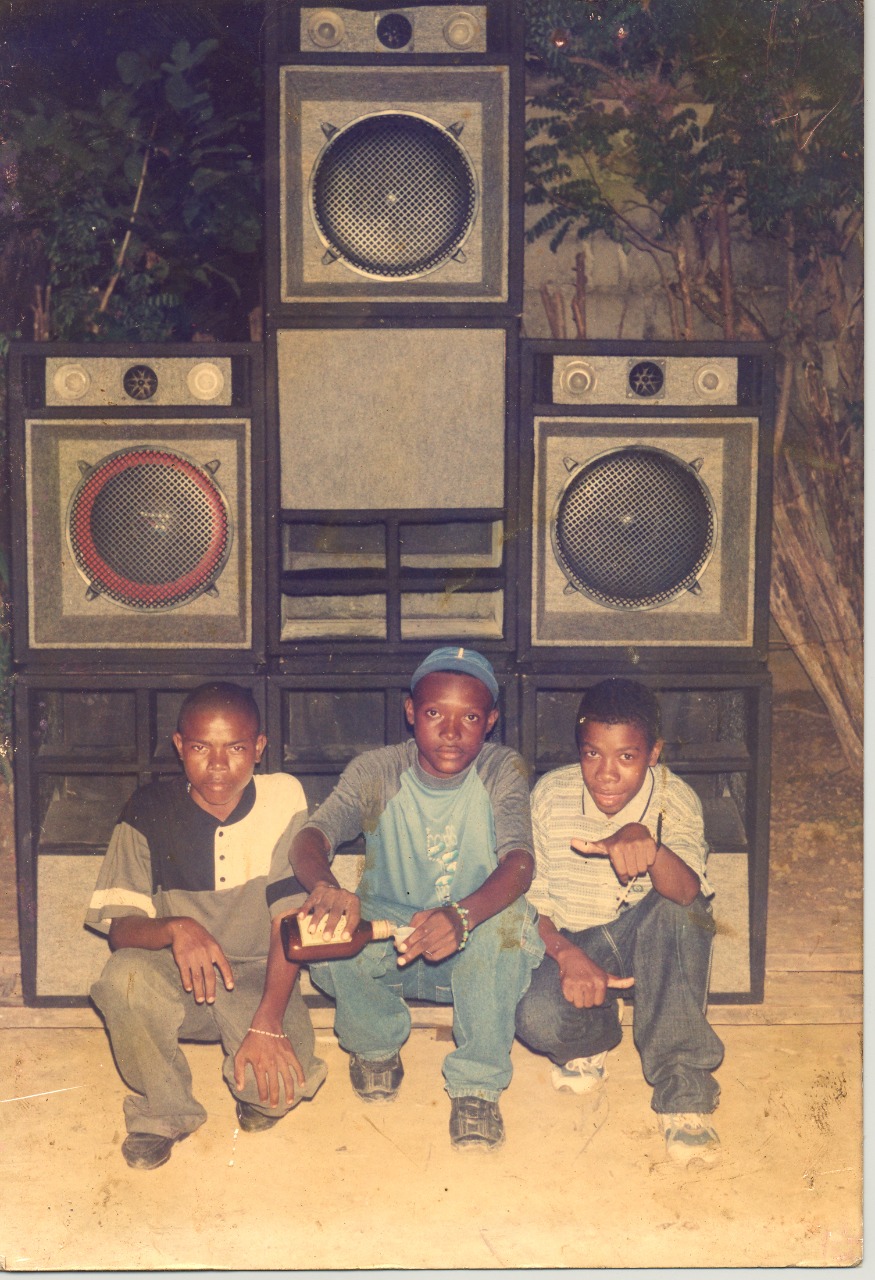

Communitary documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto

Were all the programs always done in Palenquero?

Yes, most of the programs were made in Palenquero and programming was also made with traditional music. When the radio comes out so that the community has more access, it was done taking advantage of the fact that the school was located throughout the main street and most people had to cross it, is a very strategic point, and the microphone was left open. Everyone passed by and said something: “I greet I don’t know who” and put on a song, or gave a message or information.

Why do you think they chose radio and not another medium?

Because it was thought that technology would never come here, in fact, there was a community telephone for the entire population. And the speaker was the most affordable. With a microphone and speakers it was initially done at school. Those speakers were located in different places of the institution and the people with the microphone spoke. It was a station that only worked with the lungs. And then Línea 21 said well, we can bring an antenna and they got a transmitter and a console, and that one already worked connected to an electrical device.

Communitary documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto

One of the important moments of the process was when the displaced population arrived and you went out to meet them. Why did you decide to go?

When loudspeakers were used inside the school, the stories of the students were told or stories had to be found in the street with the population. It was a student assignment. When the people from La Bonga arrived, we thought they had a lot to tell about what happened to them and there the school process was definitively removed and we moved there. In fact, I was entering the group and immediately we moved to the town and there it was possible to create another youth process that works with children.

We went out looking for stories to tell. In fact, there are still some texts from them. People did not write, but they took us as students, they told the story and we wrote it. We still have that bank of stories there, I remember one called La vida de un desplazado, another Mil noches de oscuridad.

Communitary documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto

Afterwards, the traveling cinema club also begins.

The cinema began as a strategy to mitigate the fear of the presence of armed groups. The community was very fearful and locked up very early, they went to bed at 6 in the afternoon and that was very rare. Because traditionally, people here are unionized, gathered. We thought that cinema could bring people together again. And we understood that the community liked to see themselves on the screen, in the image. Because above all, images that the Línea 21 collective already had of the territory were shown. People saw and then made a micro-story of what was in the photo, what was in the video, who they were when it was made.

And we understood that the community liked to see themselves on the screen, in the image.

You said that when you have training sessions, you achieved the space and there the group grew up …

We participated in the call for training of the Ministry of Culture, and a diploma that I did on behalf of the group, then people believed the story more. That was for eight months and we received a lot of support from the Ministry to provide equipment and support in the constant training of the group for almost three years in different areas: audiovisual, radio, media.

We began to lead to other processes: radio, community cinema and we began the process of the Audiovisual Archive of San Basilio de Palenque, which is a space where we begin to look for all that has been done, that exists on the territory of Palenque, identify where that material was and then we took that to the screen.

Communitary documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto

Then we did a very big job inside the community of appropriation of all that: what is Kucha Suto? What is the collective? What is it for? And above all to publicize the collection. That lasted almost three years. Sometimes we would go out to publicize the experience and many people said “ah, but that is not known, we do not know that and where did you do that, how long ago”.

What we did was to appropriate the community about that memory that we were finding. The work that we were developing was not disseminated by any network or anything like that, but it was more local and of appropriation.

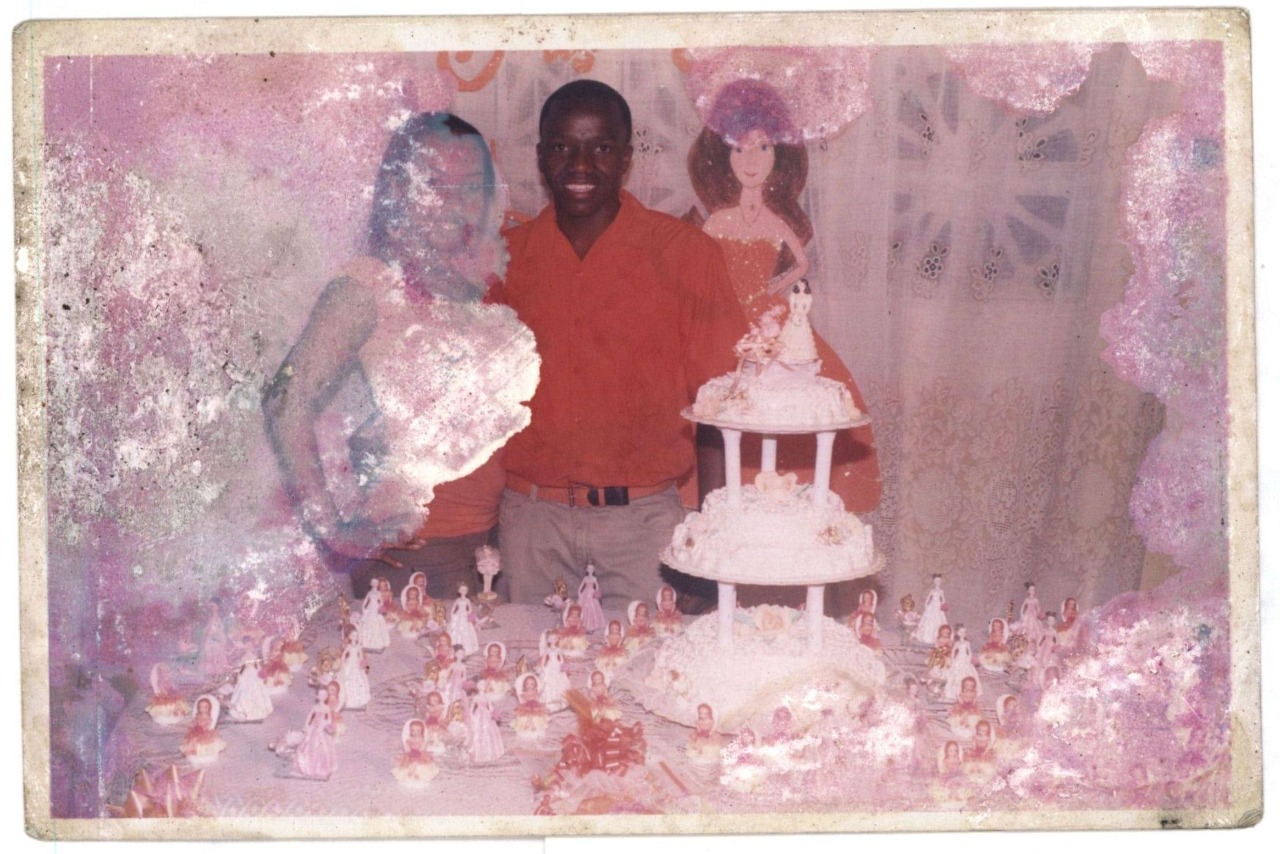

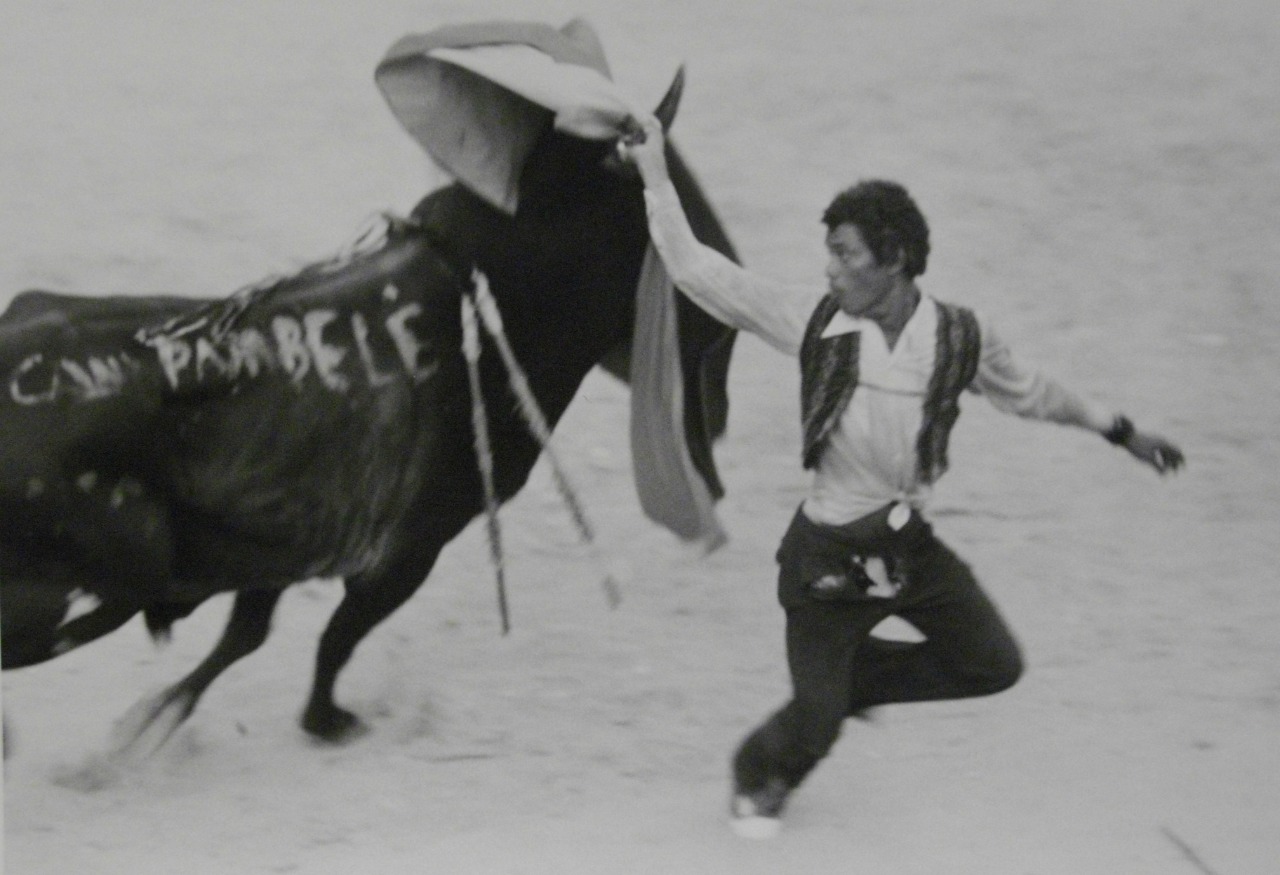

Manuel Pérez Cambiao collection

Later we saw that the group was already growing, the boys and girls already had another idea, others had to study or work. We began to think about how to sustain this process in that space, and we began the procedures to obtain legal status. Because when we asked for help, we thought it was just sayin Mr. Mayor and gentlemen, here we have a process, we are doing a very nice job and we need resources. We thought it was so. They said yes, we want to support you, but you must have this. All the institutions always told us that way and we thought it was a pretext for not supporting us. But we understood that we had to organize ourselves and start managing and participating in calls.

We returned to the La Bonga community again. Today we have a constant training process. We have a communication hotbed there two years ago and we also started making films in other sectors of the municipality, with other Afro, indigenous communities. We no longer just do the cinema club, we hold festivals where we organize processes like ours, with content made by communities, for four days.

Communitary documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto

Tell us more about the archive.

The interest started because the community said that many photographers, anthropologists, foreigners with cameras come here, they record us and we don’t know what happens with that. In addition, Kucha Suto also began to walk with a camera in hand and they began to ask us where that material was going.

We began to make lists with the information they gave. We spent almost two years searching, we made an identification and we created a database of many people, from universities or independent. Some of that material has returned.

That was then shown in the movies on the street. We took photographs elders. Everyone began to point and do that memory exercise. Then we received training on archiving and cataloging issues with the ministry.

Nina S. de Friedeman documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto rights.

Nina S. de Friedeman documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto rights

Nina S. de Friedeman documentary collection – Colectivo Kucha Suto rights

You won an India Catalina award at the Cartagena de Indias International Film Festival (FICCI).

That was in 2013. In fact, we have already started to make ourselves known. It was done with the Línea 21 collective, they have a project called El Mochuelo, which is like a kind of museum, for that project we proposed to take into account the stories of the region and the diaspora. Among these stories was that of stories and games and we made this documentary about the games and rounds of Palenquero represented by children. The piece participated in the Montes de María Regional Festival and was the winner. Hence the first three winners were registered in the FICCI and we won the best community television production for the content it showed.

Receiving that award made us understand that it was a serious process and we required much more science to continue maintaining it.

In your speech at the Visualidades Seminar you spoke of you doing things with identity. What does that mean?

When we began to support traditional music processes, young people also came saying they want to make music, but rap or champeta. The production and recording studio was just beginning, we were just putting together how the community could appropriate these spaces. In different dialogues and meetings young people said they wanted to rap, for example, and old people said no, that ends traditional music and it is not good to do it that way.

So we did a piece where they began to make fusion with identity and the young people began to make fusions of traditional music and champeta or rap, and everything in the Palenquero language. The basis of rap, for example, is not synthesized but with our own instruments.

Also in other cases, to develop a piece, a content we always create that space between our makers and the experts. If we are going to make a documentary about the typical candy of Palenque, we summon three, four men or women to make that candy and to tell us how it is made. From there you start to write and have an audiovisual or photographic proposal to give it content.

How did you find the experience of the workshop on oral memory?

I don’t do any assistance work very much, usually I’m doing the main camera or working on editing. So in this case there was a very interesting exchange with Jorge. We take care of the record, but we learned several things that we want to replicate, for example that if we work by constantly asking open questions we can generate certain conversations.