The hands that cultivate that forbidden plant

They say it’s a sensitive crop that needs a lot of care. For those who have grown up surrounded by mountains and marijuana plants – like the farmers of Cauca, Colombia – it is a habit to see them grow disorderly, experiment with them, “create” new varieties and quickly identify any insect or fungus that damages the entire harvest. Many learned to cultivate in the illegal market, but today, organized, they fight to formalize their work and demand laws that finally take the plant out of the hole of prohibition.

By Julia Lledín and Juan Páez

1. Don Ventu’s greenhouse is located behind his house, in the mountains of Toribío, in Nasa indigenous territory. Next to it, he has the seedlings he is preparing to plant when the current harvest is finished; on the other side, the flowers are drying to sell. Chickens and ducks pass by, and his two small grandchildren play among the marijuana plants. “I’m a marijuana grower. That’s what they call me at school,” one of them tells us, barely six years old. They don’t know. They don’t have to understand that these plants are a reason for stigmatization, violence, and persecution. Don Ventu tells us that he could not enter the legal market of medicinal cannabis. Of course, he aspires to do so when cannabis use for adults is legalized in Colombia. In the meantime, he will continue producing for the illegal market. His reason is simple: the crop allows thousands of families in northern Cauca to survive.

- Jairo Aguirre is an agronomist, an expert in biodynamics, and the founder, along with his son Julian, of Tierra Viva, an NGO that advises different types of crops, such as medicinal cannabis in Cauca. For him, it is essential to adapt these crops to the tropics and abandon lime. That is his main recommendation during his visit to Gold Land Cannabis, a small cooperative in Santander de Quilichao. But in Colombia, European agronomic principles are still followed, so crops are more susceptible to pests and less productive. They try to comply with legal requirements and consult experts like Jairo, to get some return from the more than four years of effort put into the process.proceso.

- The cannabis flower symbolizes a historical claim to remove this plant from the hole of prohibition. The slow path of legalization began punishing the flower: since 2016, the law allowed the sale and export of cannabis extractions (such as oils), but not the flower for its use as such. “We have become raw material producers again,” says Diana Valenzuela, legal director of Anandamida Gardens, a small company born in Cauca, in southwest Colombia. She had to move close to Medellin to survive. They have produced the perfect flower for the market: one loaded with aromas and beauty for those who defend it.

- “I left them there,” says Don Ventu’s grandson, as he accompanies, curious, the visit to his grandfather’s cultivation. Scissors, which also evoke censorship and stigma, are the everyday tool of those who “hairstyle” marijuana flowers to remove the leaves and leave them ready for sale. In municipalities such as Corinto or Toribío in northern Cauca, dozens of well-paid workers obtain the resources to support their families in a region where opportunities are scarce.

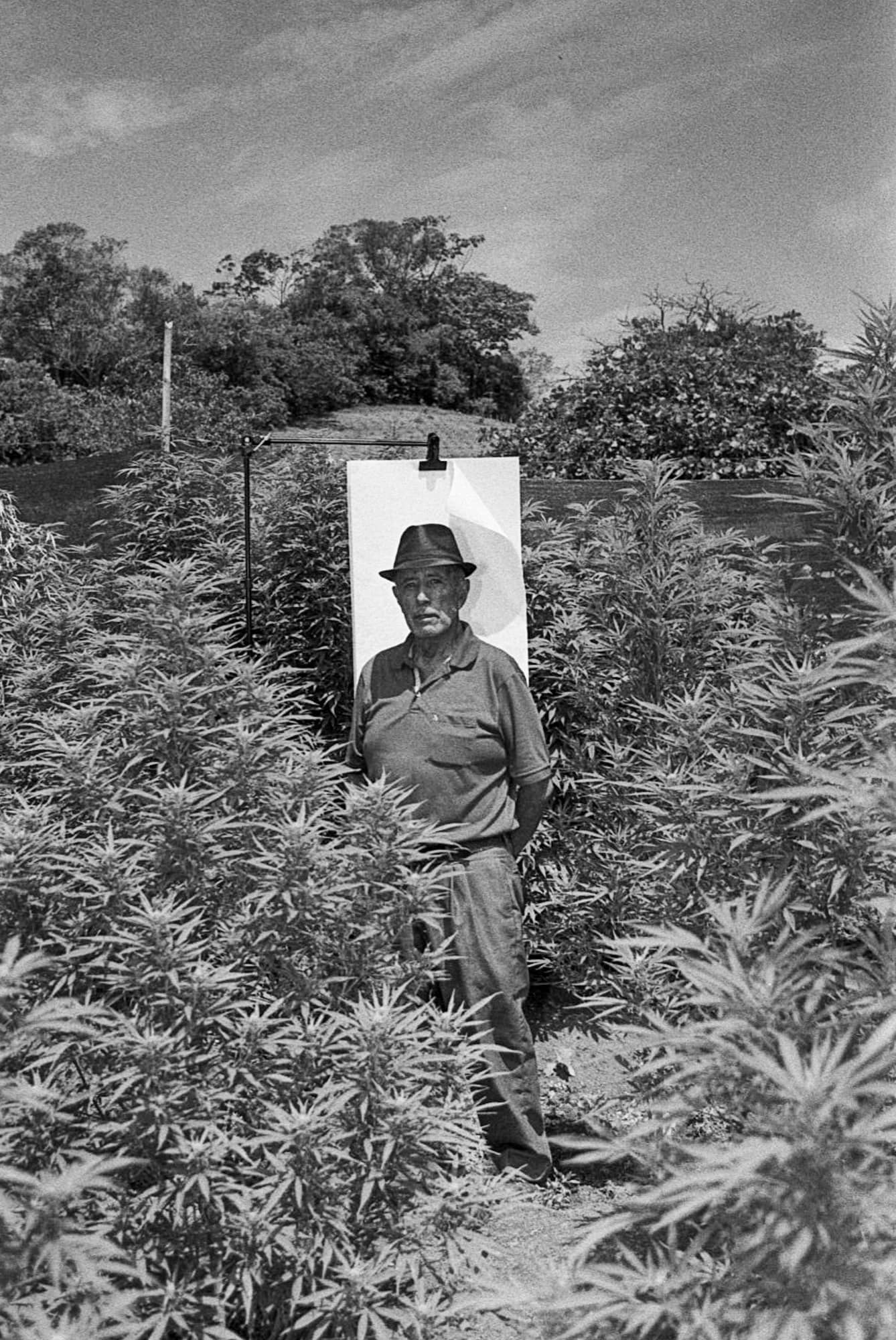

Days have passed since the holes were opened in the ground and whitewashed. They are waiting for the cannabis cuttings, prepared in a small greenhouse further up on a hilly farm, on which three greenhouses have already been built. It is the land that a small and medium-sized producers association of medicinal cannabis, based in Cajibío, Cauca, found, of which Don Artemio Salazar is a part, one of the promoters of this legal cultivation in the region. Since 2016, when he began to get involved in the sector, until today, he has faced multiple legal and bureaucratic obstacles to putting his project into operation.

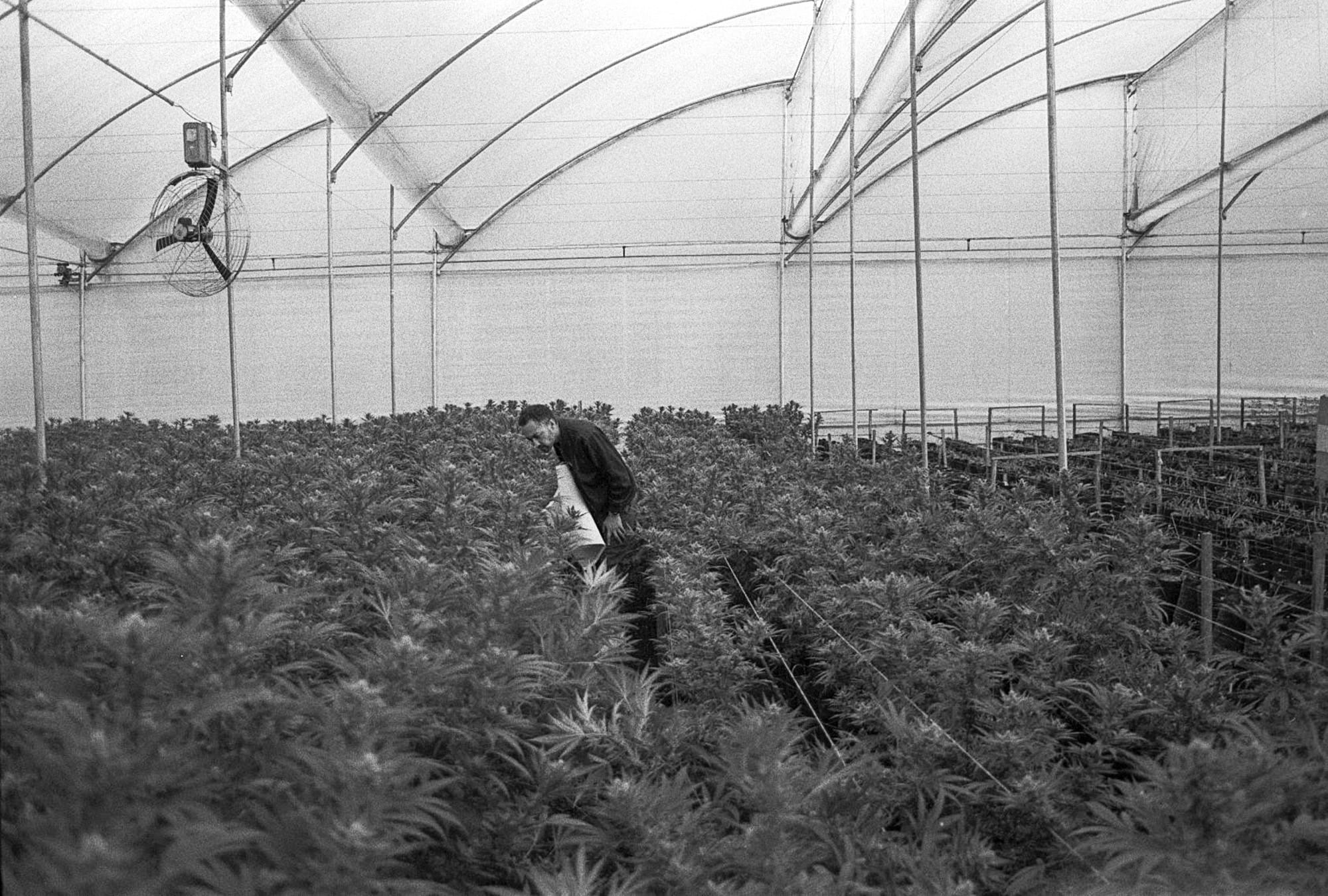

- APROCOR is a collective project of more than one hundred inhabitants of Corinto, Cauca. Associating with others allowed them to articulate with the big players and finally achieve a production contract that will bring in an income of approximately 1,000 million pesos (more than 200 thousand dollars) for the beginning of next year. Everything here is unstable. After months of inactivity due to the lack of buyers, they need to organize everything to ensure compliance with the commercial agreement. The cultivation is filled with people, and every corner of the 20-hectare farm they have rented is full of activity. Women take care, among complicit conversations, of preparing the cuttings with care and the security that collective knowledge provides.

7.Corinto is divided between the mountainous and the lowland areas.Geography establishes a natural border between illegality and legality. Up above, there have been prohibited marijuana crops and also illegal armed groups for more than four decades; in the lower part, legal crops, mainly sugarcane and coffee. The legalization of medicinal cannabis six years ago brought the expectation of reversing the stigma that weighs on the region and turning it into an opportunity for development and differential positioning in the market, as one of the best marijuana in the world is produced here. However, peace did not take hold. The medicinal cannabis projects also did not bring the first benefits. The stigmatization continues, and the border persists in the geography and people’s minds.

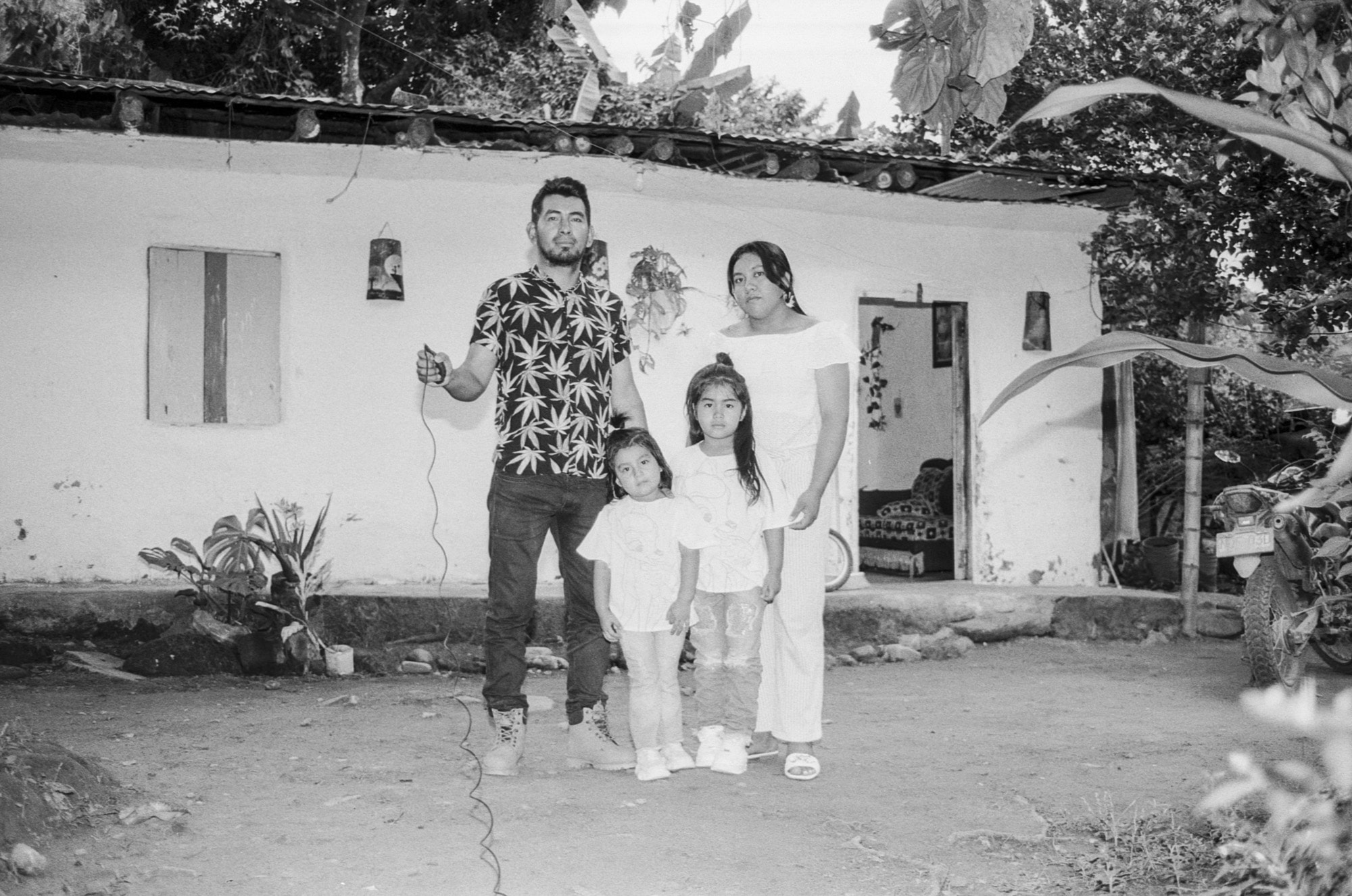

- The stigma comes from outside because it does not exist here. The cultivation of cannabis in northern Cauca is just like any other. Its knowledge is passed down from generation to generation without distinguishing between ideologies or creeds because it is the economy that supports hundreds of families in the region. Jefferson Chiquito’s family is Christian; they are photographed in front of their house, in the rural area of Corinto, on their way to mass, the woman in white, he with his elegant shirt decorated with the marijuana leaf. He dresses this way to claim, that obscures from a distance, that everyone deserves the opportunity to live.

- Alexandra Torres is an administrator and leads the Corinto Producers Association, APROCOR, created in 2017. She learned to move like a fish in water between politics and the cannabis business sector because both sides need patrons. She has just achieved success: signing a contract with a large company, Biominerales Pharma, which will finally give her association, made up of 150 families, its first income. APROCOR was created with the expectation of becoming an option to improve lives in the municipality of Corinto. Alexandra knows that these incomes will not only benefit her members: they will also help to build public infrastructure and social programs for the community.

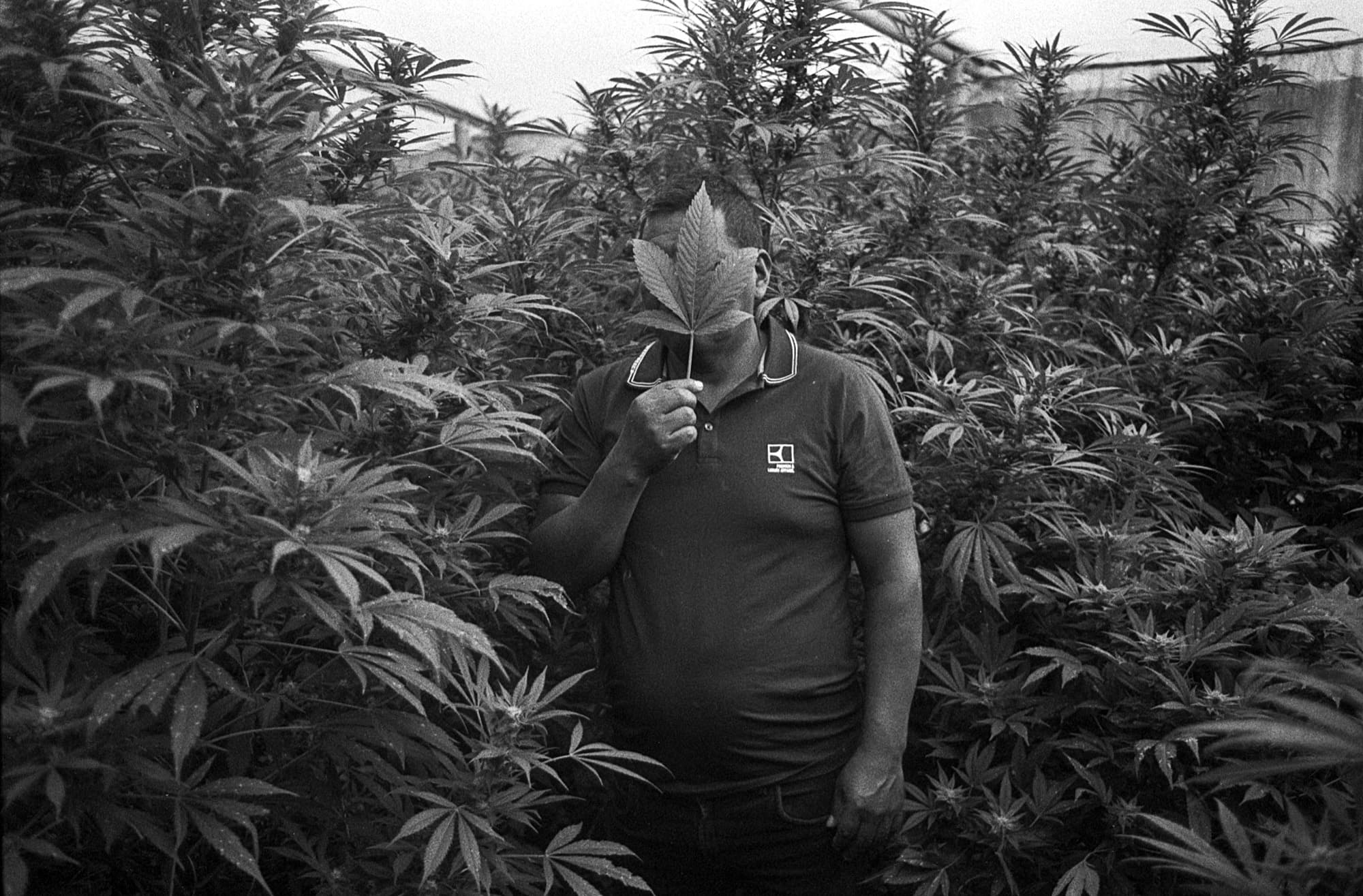

- Julián Caicedo is passionate about cannabis. He enjoys smelling the aroma of the plants that fill the greenhouse that he and Anandamida Gardens have built-in Rionegro, near Medellín, Antioquia. It is the perfect crop. The technical improvement allows for the concentration of terpenes, highly volatile compounds that give smell and flavor to cannabis and whose quality provides value to the flower in the medicinal market. His project is more than a business opportunity; it is about changing the perception of the plant, protecting it, and positioning it as a crop with enormous healing potential, both physically and emotionally., física y emocionalmente.

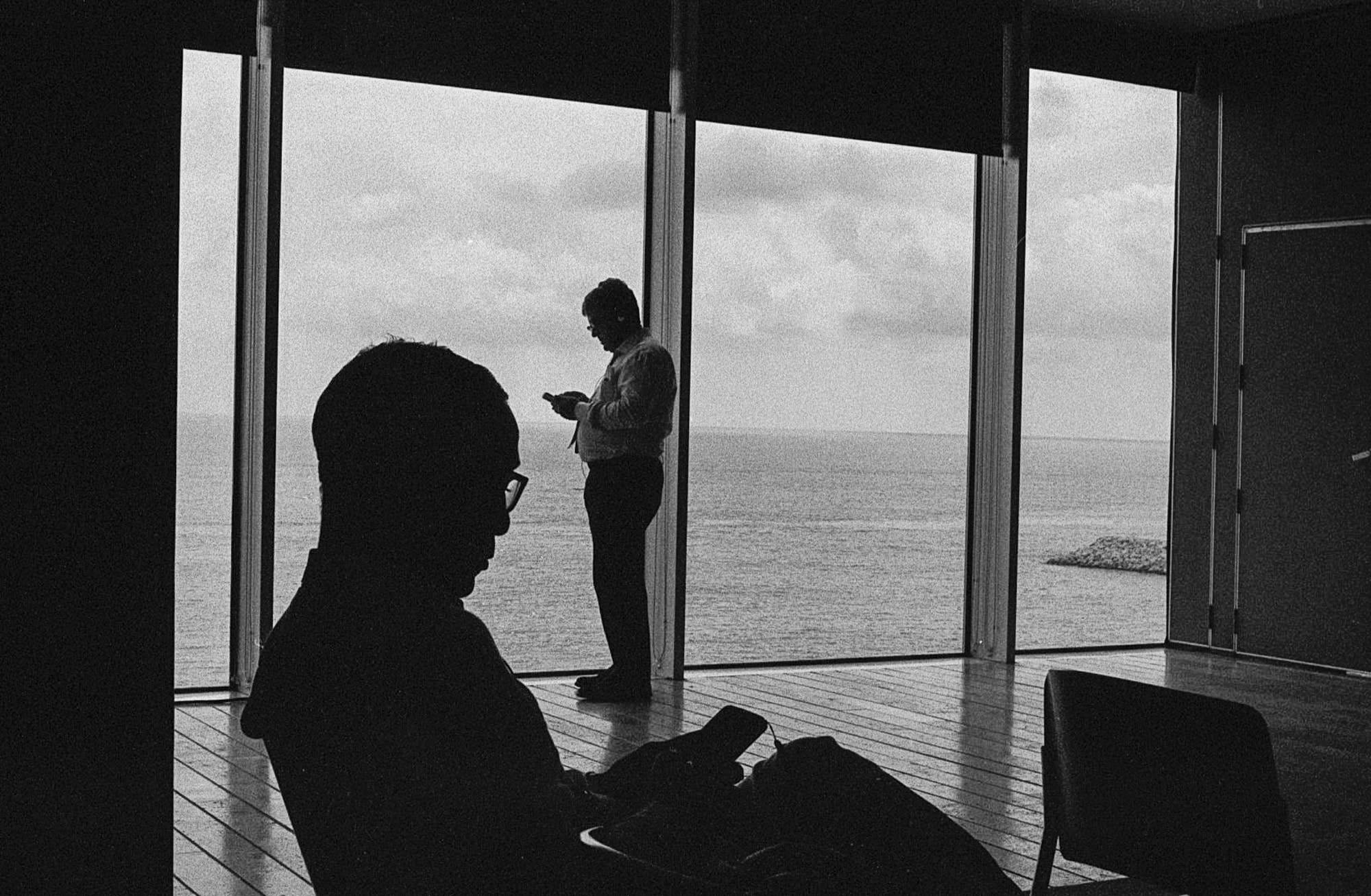

11.Expocannabis Cartagena is one of the privileged stages for speculation and the sale of future expectations, which occurs between the sea’s mildness and the anonymous sobriety of global markets. The congress began by bringing together most entrepreneurs interested in the sector. One of those places where national and transnational networks are woven that have sold medicinal cannabis as the new “green gold.” Expectation or reality? These networks are also the origin of legislative changes opening the way to take cannabis out of the hole of prohibition.

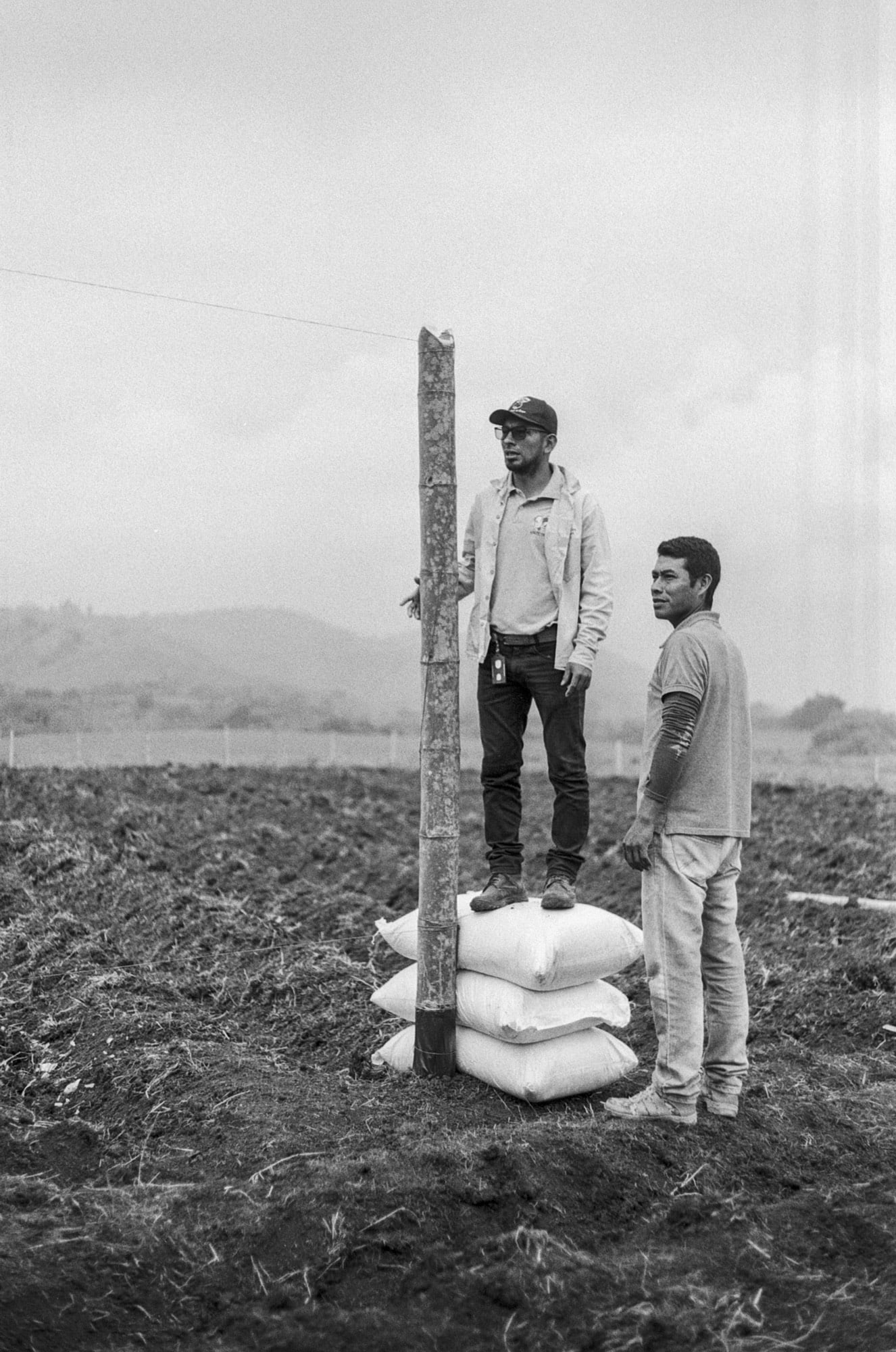

- Jefferson Chiquito and Omar Largo are cousins, Nasa indigenous people from Corinto. They work carefully, taking care of APROCOR’s cannabis plants. Among bags of fertilizers and fertilizers, increasingly expensive in the market, they work to make the land productive. They try to reach the summit of success in an economic sector where only some will manage to get and stay. They look to the future, trying to anticipate if they will be among the lucky ones.

13.That is the paradox of surveillance in a place where the state does not rule. Each psychoactive cannabis crop with a license must have a surveillance system to prevent legal production from feeding the illegal market. The fiction of control, established by law in Colombia, clashes with the green landscapes of northern Cauca, unpaved roads, mountains without telephone signal, the frequent noise of the armed conflict, multiple realities that intersect to allow, day by day, the resistance of dignity.