All the wars I saw

It is no secret that the history of photography has been told, above all, by men. Perhaps that is why, in places like Colombia, the story of women photojournalists has yet to be said. Zoraida Diaz was one of them: in the early nineties, she was the official Reuters photographer in her country, and when she had to leave because of the violence, she was chief photographer, section editor for the Southern Cone, and photo editor for Latin America at the same agency. Díaz opened the way for other photojournalists to build with her photos the memory of a country that still bleeds.

By Marcela Vallejo

-I managed and practically ran away from home. My parents were shocked, but that’s how I arrived in Colombia in 1987. They thought photography was just a hobby.

In reality, that’s how Zoraida Diaz returned to Colombia. She was born in Bogota to a middle-class family. When she was eight years old, her parents decided to emigrate to the United States, following in the footsteps of her paternal aunts, who had already settled there. In that foreign country, the first thing Zoraida missed was the mountains.

Today Zoraida lives in Maryland, United States. She returned after a long career working for the press, first for Reuters, where she worked as a photojournalist, chief photographer, section editor in Argentina, and then photo editor for Latin America in Washington. Then, searching for change, she returned to Central America, where her passion for photography had been born years earlier. She lived in the province of Guanacaste, Costa Rica, where she took up documentary photography again and created a local newspaper with her partner. A couple of years ago, she took a master’s degree in creative writing, which gave birth to her memoir The Altering Eye.

Zoraida says in that book that she returned to Colombia when she was 22. She returned to live in her childhood home, across the street from the Escuela Militar de Cadetes, searching for roots she felt she had lost.

Youth, she says, made her move with curiosity and energy. She wanted to see what she had read during her university education in literature, to know what appeared in the novels of the Boom authors, and to do it through her camera.

By then, she had already worked at the Reuters Latin American editing desk in Washington, translating the captions that accompanied the images. There she became friends with several of the agency’s photojournalists working in the field, especially Bob Strong. He proposed she work as a stringer to collaborate with the agency.

When she decided to travel, the “big stories” that interested the international press had already happened in Colombia. In 1985, the country went through a huge natural disaster and an unprecedented event: the Armero avalanche and the seizure of the Palace of Justice by the M-19 guerrillas.

-In the beginning, I worked as a freelance for the agency and did other, more personal things. I didn’t understand what was happening in Colombia, but little by little, I established contacts.

After ten months, she managed to establish relationships for one of the trips that would change her way of seeing and understanding her country. In her memoirs, she recounts that the instructions she was given before traveling were few: to pack what she could carry, some non-perishable food, some marsh boots, clothes for the cold and the heat, and a raincoat. In addition, she took a package of roasted culonas ants and a bottle of brandy.

Her father, who had come to visit from the United States, was surprised by the combination and asked her where she was going. She quickly said that she was going to the eastern Llanos Basin of Colombia and that the ants and brandy were a gift. When she packed her suitcase, her dad returned, handed her a bottle of cognac, and said, “If you’re going to Casa Verde, you can’t go wrong.” Of course, he knew who those ants were for: Jacobo Arenas, one of the founders of the FARC, was from Santander. Someone who could enjoy that curious gift.

Her father did not try to dissuade her; he knew how stubborn she could be. He just told her he hoped she would take advantage of it and do more than take pictures. “The present is built on the past,” he told her and reminded her that, years ago, he, his family, and many other peasants had had to abandon their land to survive the violence (with a capital “Violencia”). It had also touched him very closely, as his brother died in the Bogotazo, in 1948 during the riots over the assassination of Liberal candidate Jorge Eliecer Gaitán.

“My father wanted his eldest daughter to assume that to be Colombian was to carry those weighty stories, like Atlas,” she recounts in her book. “Even though I had returned to my birthplace and insisted on photographing the worst impulses of my countrymen, I was still judged free of past sorrows, too indifferent, too oblivious, too United States.”

The journey to Casa Verde

In the country where stories of international interest were scarce, that year, 1988, everything was beginning to stir. Peace talks with various guerrillas united under the name of the Simón Bolívar Guerrilla Coordinating Committee were in full swing. The FARC guerrillas were in Casa Verde in an increasingly threatened truce. The genocide of the Patriotic Union (UP) militants, a political party, associated with the FARC that was born with the peace talks in 1984, was already undeniable. “Todo pasó frente a nuestros ojos,” the report of the Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica, records for the period 1984 to 1988, the point at which violence reached a critical moment, 1680 victims, of which 1280 were killed or disappeared.

Casa Verde has also been called the sanctuary of the FARC. At first, it referred exclusively to the headquarters of the FARC’s historical leaders, such as Manuel Marulanda ‘Tirofijo.’ That changed with time and security needs, but the name was kept to refer to the area in the canyon of the Duda River. Later, the headquarters for command meetings were located in El Rincón de los Viejitos. There was a telephone in direct communication with the Consejería de Paz (Peace Council). The combatants’ camp, known as El Pueblito, was a few minutes from the now-extinct village of Ucrania in the municipality of Uribe (Meta) on the canyon of the Duda River.

Pedro Antonio Marín Marín, better known as Manuel Marulanda or Tirofijo, was a peasant belonging to the Peasant Self-Defense Forces of southern Tolima in Marquetalia. A group that, together with the Marquetalianos, survivors of Operation Soberanía, would form what would later become known as the FARC guerrilla group.

By 1988, this guerrilla group had almost 6,000 combatants. It had been in an unstable truce for six years during fragile peace talks that began with the government of Belisario Betancur and, with difficulty, were maintained with the government of Virgilio Barco. The constant vigilance of the military forces diluted the idea of Casa Verde as a sanctuary and refuge. In this context, Zoraida arrived on a trip that took several days and was an unforgettable experience.

-It was when I understood everything. Perhaps not living in Colombia made me see the situation from a distance. I saw the problem, but I didn’t understand it very well. I didn’t understand the deep social unrest that existed at those levels. Arriving there was an experience that taught me that, in reality, ours was a divided country. It was like traveling to another reality.

She took the luggage instructions to the letter. They left through Usme with other journalists, and the guides made them cross the Sumapaz moor. Two days into the trip, she could not take it anymore. What she had brought to protect herself from the cold was not enough. The guides got them some horses on the third day. When they arrived at the camp, Zoraida was surprised by what she found:

-It looked like a tiny wooden town. It even had houses with gardens. It had a school, a saddlery, a bakery, and a tailor shop where they made uniforms. It was open, and Arenas walked around with his “red telephone.”

It was El Pueblito. Darío Villamizar in his book ¡Atención cae Centella! La operación Colombia o el mito de Casa Verde, tells that the routines in El Pueblito were the same as in a guerrilla camp. The schedules were established with a whistle, and a different activity began with each call.

When Zoraida arrived, ‘Jacobo Arenas’ received her and told her that she had to have a name like everyone else in the camp. He named her ‘Dalia.’ On that trip, she learned many things. She felt she was entering another country without strong ties to urban Colombia. A world where the guerrillas built the roads and bridges, where they represented authority.

On that trip, she learned many things. She felt she was entering another country without strong ties to urban Colombia. A world where the guerrillas were the ones who built the roads and bridges, where they represented authority.

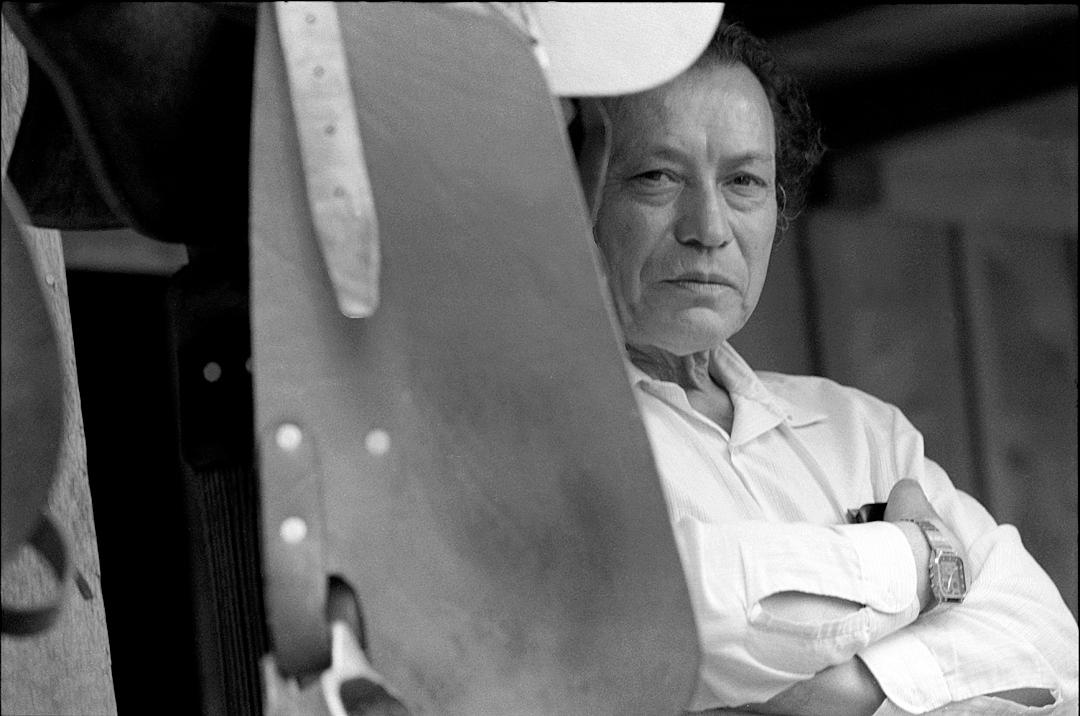

The atmosphere in the camp was increasingly tense, and the overflights of the military forces were more frequent. Despite this situation, Diaz gained a lot of trust from the people and made many portraits of different combatants, some very young and of the leaders. During this visit, Manuel Marulanda summoned her and the other journalists to interview him.

When she arrived, she felt uncomfortable. She could not find the right angle or light for the photos. Tirofijo would not get up from his chair, and the only thing the photographer could do there would look like any other press conference photo. The interview was short, and he dismissed them. Then she jumped in and suggested moving to another place where the light was better. The commander looked at her in surprise.

-Please,” I said, “look, the shots from this one don’t hurt,” pointing to my camera. I think he was amused, laughed, and agreed.

She found it interesting that many horse mounts were hanging from the ceiling. She asked him to stand over and take the picture in two seconds. On the left side, you can see one of the mounts covering part of his body. Marulanda has a light shirt, a watch on his right wrist, messy hair, and crossed arms; he looks at the camera without smiling. His gaze is calm, and his face already bears several age marks.

That calmness and confidence, in part, Diaz says, has to do with the fact that she is a woman. Asked what her experience was like as a woman and a photojournalist at a time when very few of them, she says she was fortunate to be young, but she also says it was difficult to place her. Zoraida is thin and tall, taller than the average Colombian, with angular features and small eyes. At the time, she wore her hair short, something uncommon for local women, and no one knew for sure if she was Colombian or not.

-Being a woman in certain instances helped because a woman did not inspire the same suspicion and distrust as a man. The camera and the reporter tend to be invasive, and although being an agency photographer is a highly competitive profession, mine was always measured and slow. Not only did I not want to take photos that looked like those of my colleagues, but I also wanted to delve into the non-verbal communication essential to documentary work.

In the midst of the cartel war

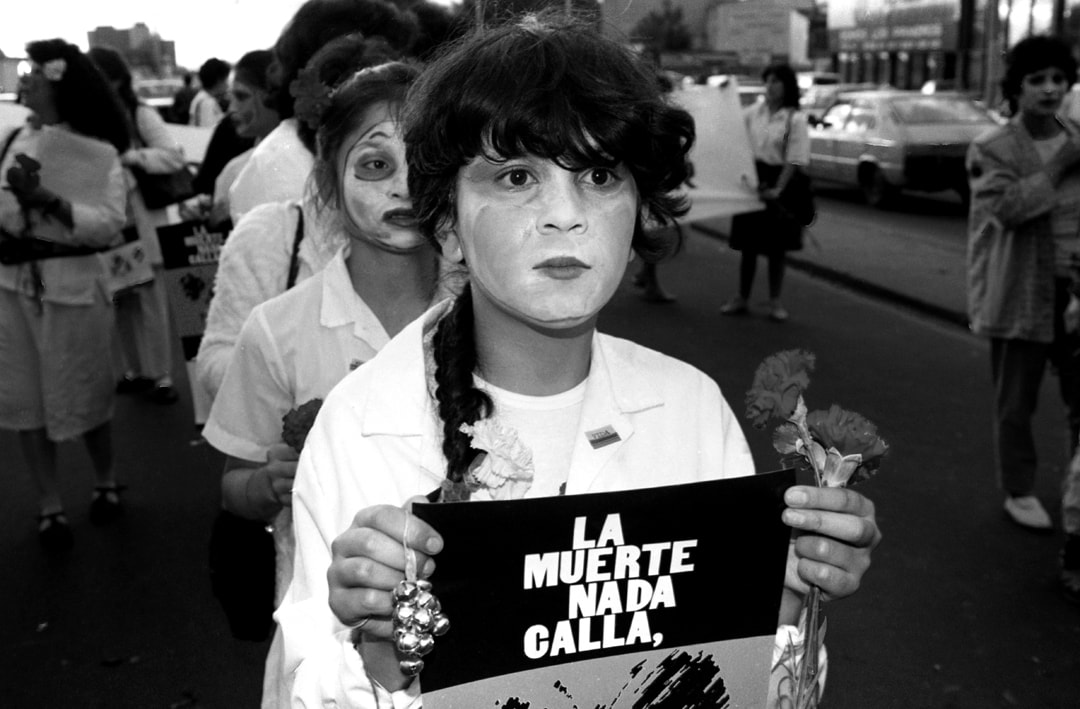

After Zoraida’s trips to Casa Verde, things began to happen that made Colombia once again a focus of interest for the international press: the fight against the drug cartels was gaining strength, the peace negotiation with the guerrilla Coordinator, the bombing of Casa Verde, the massacres and an assassination. In 1988 alone, more than 600 deaths were recorded in various massacres, in which the most affected were the militants of the Patriotic Union in the so-called dirty war. Everything was finally unleashed the following year.

Experts such as Hernando Zuleta say that 1989 was when the Colombian State lost control. The Medellín cartel had so much power that it could declare war on the government. If in 1984, they had crossed many limits with the assassination of the Minister of Justice, Rodrigo Lara Bonilla, an event marked as the beginning of the War on Drugs in Colombia. In 1989 they proved that there were no more limits; journalist María Elvira Samper, in her book 1989, calls it the most violent year in recent history. On August 19 of that year, Luis Carlos Galán, presidential candidate for the New Liberalism party, was assassinated.

-I think that the bloody struggle between the State and drug trafficking began with the death of Galán. On August 20 was the funeral, and there were crowds at the burial. By that time, I had accompanied the Police and the army in some operations against drug trafficking at the beginning of 1989. I have many photos of burning laboratories, the destruction of tons of cocaine, and mock confrontations.

When Galán was assassinated, the president at the time, Virgilio Barco, made a declaration of war. According to him, the results obtained up to that moment were “great and concrete.” That month, the president declared a state of siege because not only Galán had been assassinated but also the commander of the Antioquia police, Colonel Valdemar Franklin Quintero. And with that decree, Barco also reestablished extradition.

-At that moment, I called all the contacts I had built up in the Military Forces and the Police during two years of work. I proposed to them to show what they were doing to combat drug trafficking.

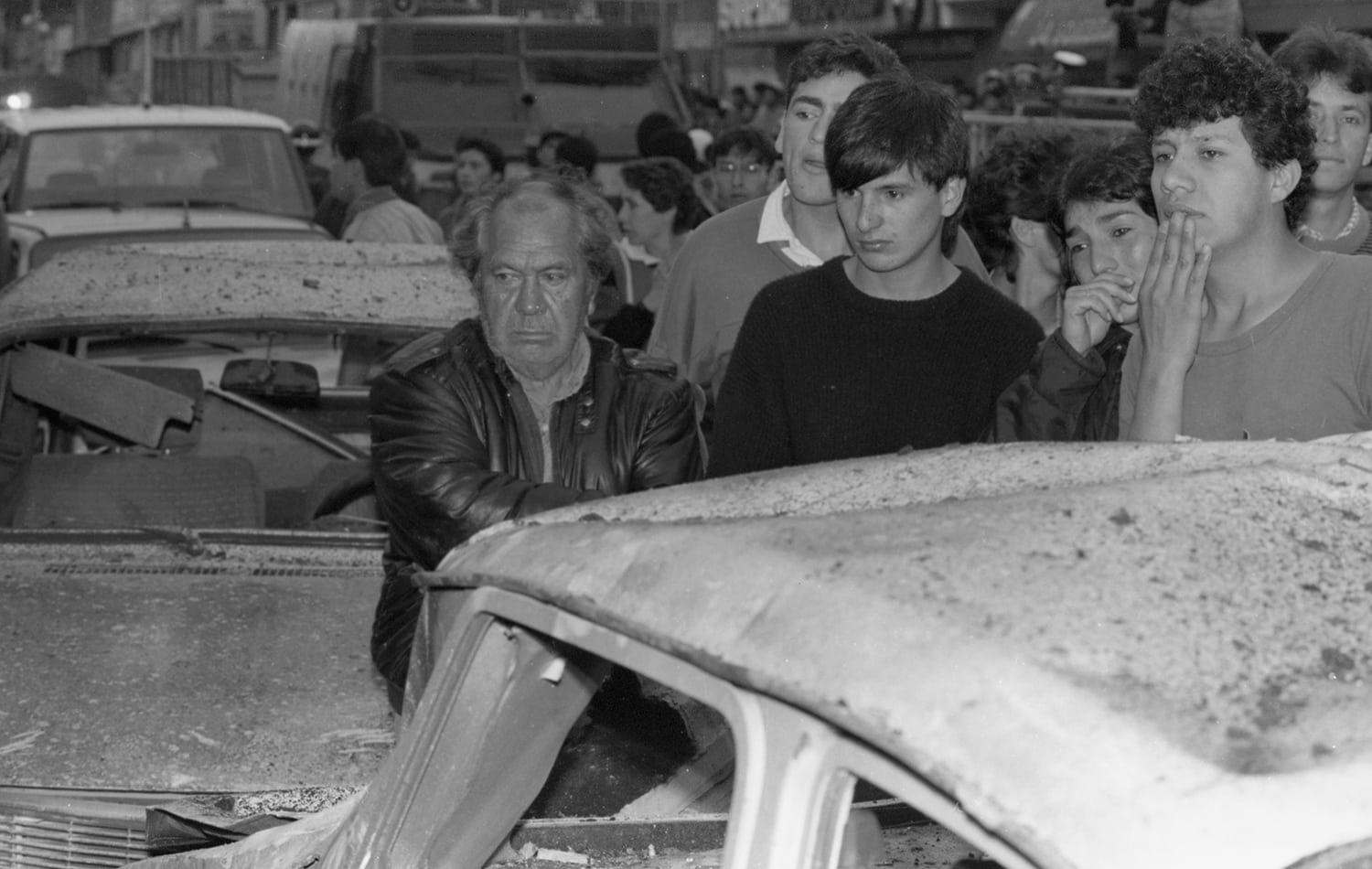

Of course, it wasn’t all successful operations against drug traffickers. Diaz has a massive archive of the terrible effects of the “big” and “little” bombs that the Medellin Cartel regularly planted.

-For example,” she said, showing a photo of the ones she sent to the agency. This is a caption of one of the photos I sent at that time: “a car bomb explodes on November 3, 1989, and kills four people under a bridge.” We called those bombs little bombs.

Among the “big bombs” was the attack against the building of the now-defunct Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad (DAS). The explosion of the car bomb loaded with 500 kilos of dynamite resulted in 63 dead and 600 wounded. The images are horrifying: the structures of the building are collapsed, only rubble and people watching what is happening. That was one of the responses to the “extraditable.”

The risk was not only for the politicians in office. Between 1986, starting with the assassination of the director of the newspaper El Espectador Guillermo Cano by hitmen hired by Pablo Escobar, and 1995, 62 journalists were murdered. Most of the alleged perpetrators were drug traffickers. Zoraida felt the tension and knew that, although she had certain privileges, she had to be careful.

-Being from an international agency, my work was not seen in the country, and when it was seen, the newspapers usually did not put the name of the photographer but only the agency’s name. That helped my work and what I did to be anonymous. My photos were much more recognized outside Colombia.

Her departure from the country occurred after Pablo Escobar’s death and a couple of strange situations. One day in 1991, she was on her way to her office in the old El Tiempo newspaper building in front of Santander Square in Bogota. There were also the offices of the emerald miners. Diaz was waiting to cross the street when suddenly a woman stood next to her.

-She looked at me and said, “Dalia.” I was startled, but I greeted her back. She said, “I was just saying hello,” and kept walking. I was super tense because I imagined that meant they were looking at me from both sides.

After that, between 1993 and 1994, in an extraordinary way, two stray bullets entered her apartment in downtown Bogota. By then, she had already had a newborn baby. And although she had not received any direct threats, that incident with the bullets precipitated her departure from the country.

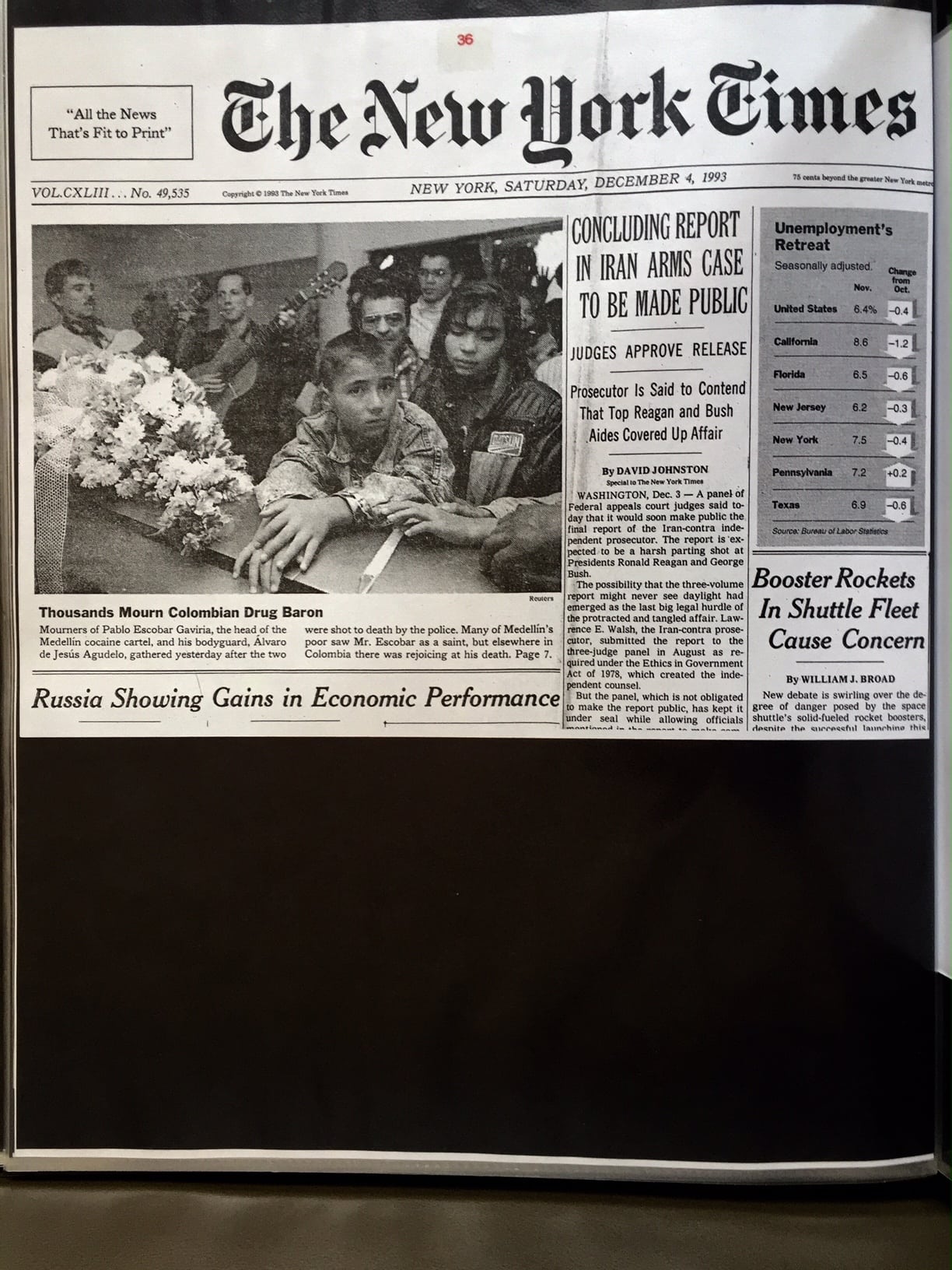

Then Pablo Escobar died. The day he was killed, Zoraida was in Bogotá. She arrived in Medellín at night. Henry Agudelo, from the newspaper El Mundo, who collaborated with Reuters, was covering the event.

-I knew that the next day things were going to happen. So at four in the morning, I went to the cemetery, and there were already many people.

The line at dawn was huge. At wakes and funerals, it is common for many people to go to ask favors of the souls of the dead. Escobar was very popular in the slums of Medellín. When she entered, the coffin was open, and she could see the body with wounds and bruises. She went through her camera, and it had already been closed when she managed to get back in. In any case, she was not interested in taking that picture. In the room, there were two coffins: Escobar’s and that of Limón, his bodyguard. When she returned to the room, she was shocked that no one surrounded Escobar’s coffin. Limón’s coffin, on the other hand, was surrounded by his family, and on top of it was a little boy crying, trying to hug him.

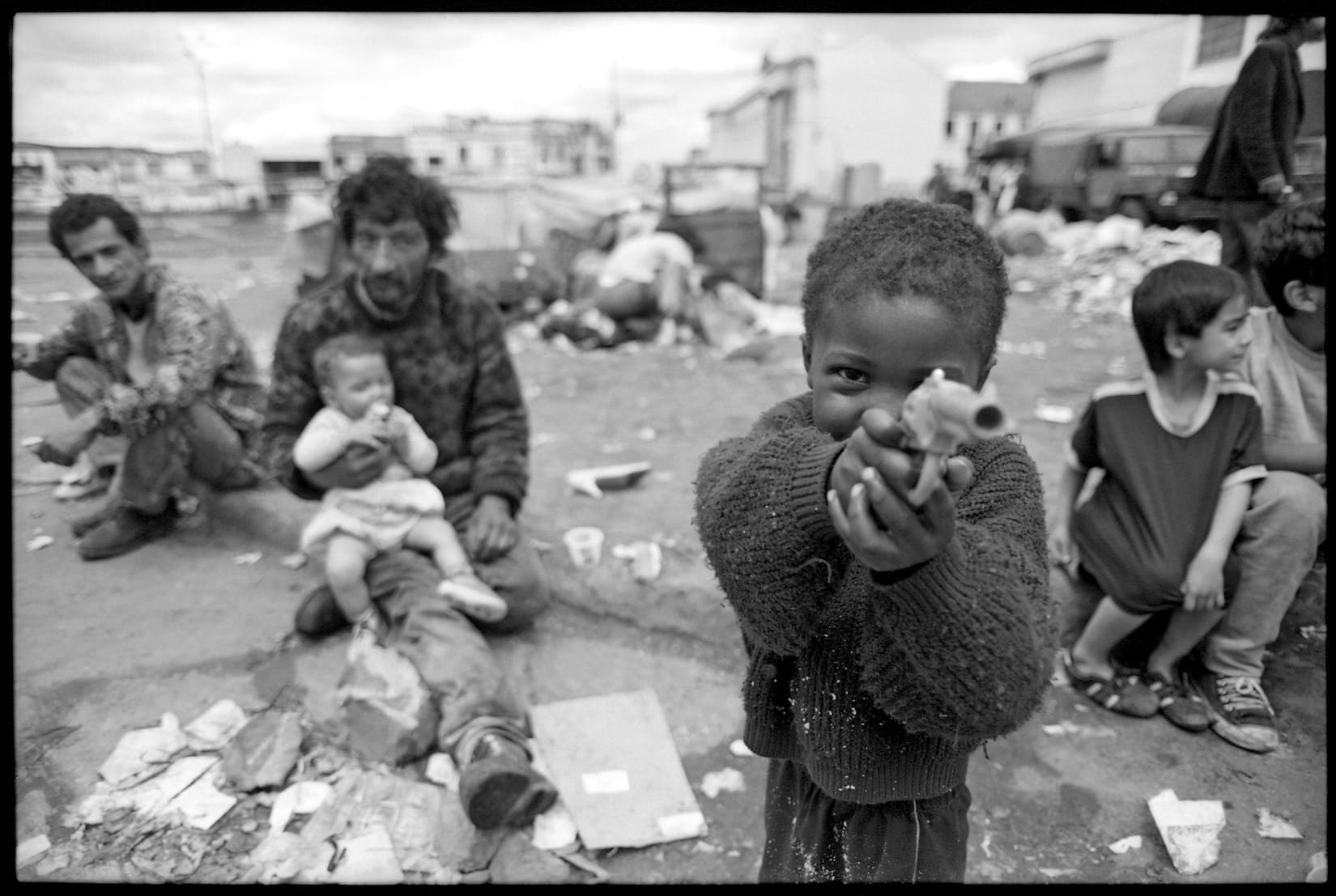

-It made me so sad. So I thought that Escobar’s photo didn’t matter. The picture that I worked on the most and that interested me the most was to capture the look of that child, which creates that chain of violence that doesn’t end. For me, that was the end.

Then she took some photos of Escobar’s family when they were being held at the Tequendama Hotel. “There, too, the image that struck me was when I saw the daughter, a girl of about nine years old, self-absorbed and sad.” In the photo, she is looking out the window on a high floor of the hotel. “I was always struck by how all this affected children in particular.”

Out of the commonplace

In Colombia’s history of photojournalism, there is a record of few women photographers. Sometimes the lack of knowledge has made them invisible, but they have been part of and have contributed to the development of photography and journalism as in other countries. In the 1980s, the work of several women photojournalists was recognized: Vicky Ospina, Patricia Rincón, Luz Elena Castro, and Liliana Toro. Zoraida was characterized because soon after, in 1990, she became the official Reuters photographer in Colombia and because, from the beginning, she was on the scene of the events.

After leaving Colombia, Zoraida went to Buenos Aires, and at Reuters she was assigned the position of Chief of the southern zone; that is to say, she coordinated the photographers of Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, Paraguay, and Uruguay. In 1996, the story she edited on the seizure of the Japanese embassy by the MRTA in Peru received an award at that year’s Worldpress photo. A year later, she was promoted to general editor for Latin America and returned to the United States.

Despite such a trajectory, Zoraida is not a recognized photographer in Colombia. That is partly because her name did not commonly appear next to her photos. Only the agency’s name appeared. Although, at the time, that meant her some protection in an increasingly hostile environment, the truth is that it increased invisibility that is increased to the fact that she is a woman. However, she portrayed a time of many events and changes. And her work is relevant not only because of that but also because she was the witness who took many of those images to the international press.

Why is she not better known? It’s no secret that men have told the history of photography. For that reason, the story of women photographers has yet to be said in places like Colombia. Although more and more people are becoming interested in doing so: experts like Juanita Roa say that what has been written about women photographers is still in its infancy, especially in photojournalism.

Knowing the story of women like Zoraida is essential because they opened the way for many others. But also because it is necessary to stop imagining that this has been a profession for men, an idea that limits women and gender dissidents who want to embark on this professional path and erases the possibilities of telling what happens from other points of view.

Knowing the story of women like Zoraida is essential because they opened the way for many others. But also because it is necessary to stop imagining that this has been a profession for men, an idea that limits women and gender dissidents who want to embark on this professional path and erases the possibilities of telling what happens from other points of view.

According to a survey conducted by World Press Photo, today, only 15% of professional photojournalists are women. Whether the photo made by women is different is not so easy to answer, but we do not have enough references to say it with certainty. One of the things that Zoraida identified in her work was that the fact of being a woman allowed her more closeness. She relates it to “not producing a sense of fear or danger.” Perhaps it is a way of approaching and seeking other ways to engage with the stories.