And You, Why Are You Black?

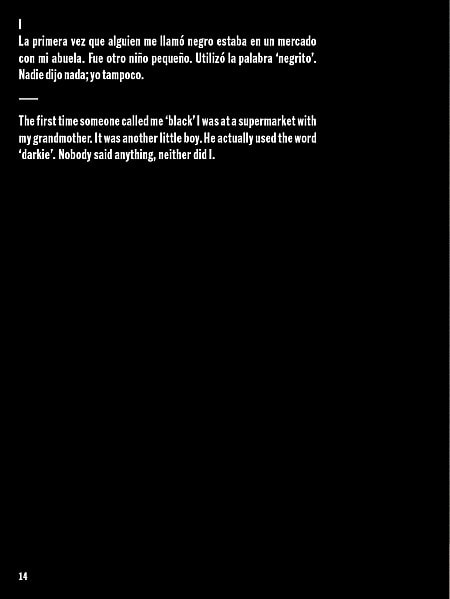

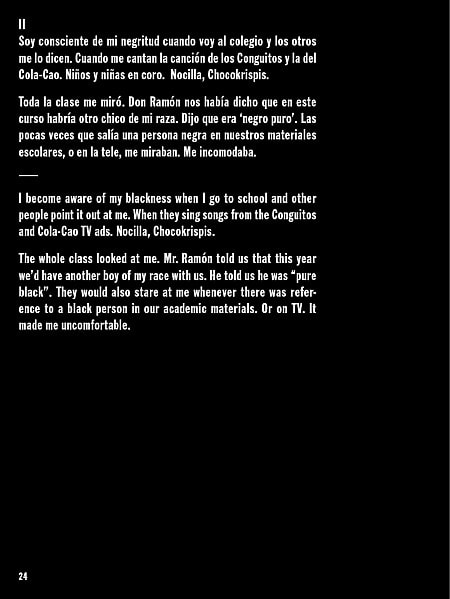

Spanish photographer Rubén Bermúdez is fan of Atlético de Madrid. One day he went to the field to see a crucial game, which could make him champion of the League. However, the team lost and he walked home. On the way he met a black person and they began to talk, they shared a few blocks. At some point, Rubén said that he was Spanish and that his parents were too. Then the man said: “And why are you black?”

It was not the first time he had been asked that question. In fact, it was asked quite often and he never knew what to answer. But tonight the comment came from a black person, like him. He went home and started a blog that he called, of course, y-tú-por-qué-eres-negro.

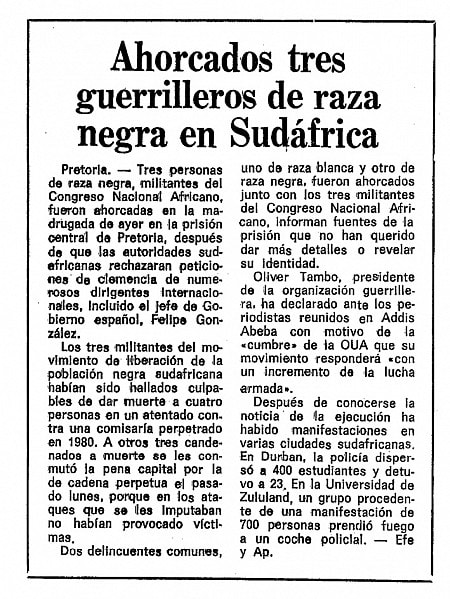

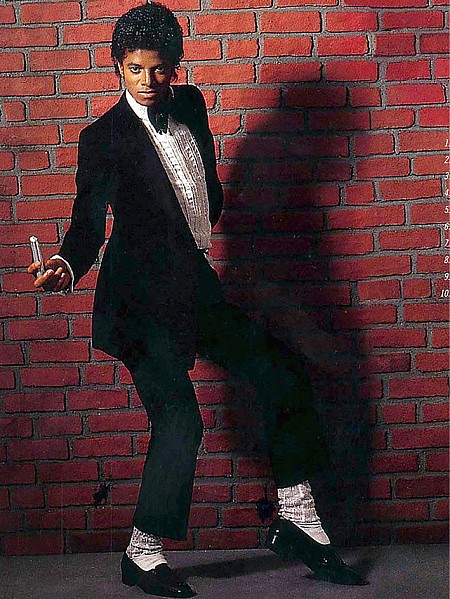

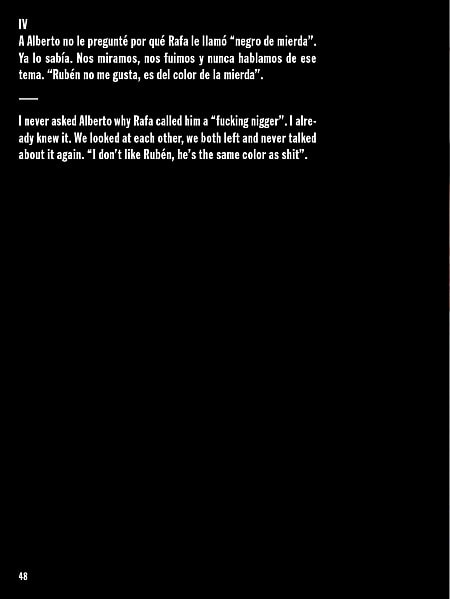

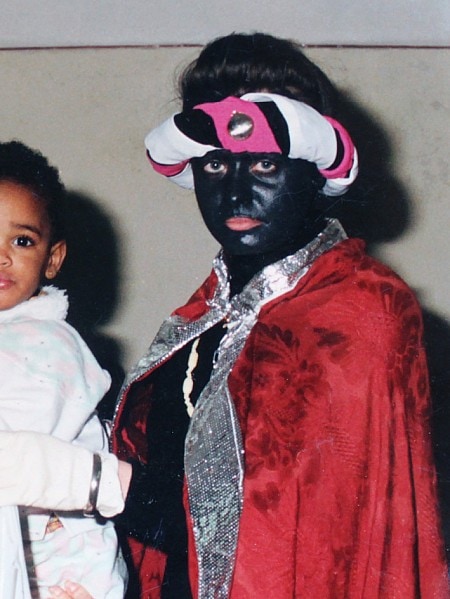

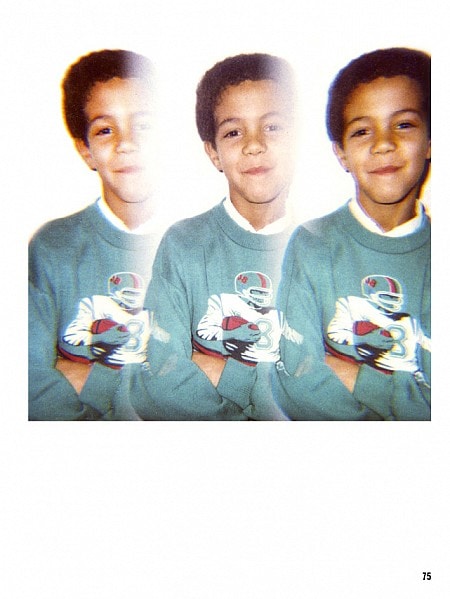

In 2017, that idea became a book. In these pages with a black background, the photographer reflects on the origins of black slavery using the images and symbols of his daily life and history. He also wondered about the photograph because, as he studied it, he noticed that all the references were from white people explaining what the world was like. “The camera itself, the politics of the apparatus, is racist,” he interprets.

The visual stories made him connect with many people, they contact him to give him material and tell him that they felt identified. “Many Afro people who live in countries with a white majority have similar experiences,” Rubén says. His book and other works by him are putting diverse stories on the agenda.

Photo book And you, why are you black?– Rubén H Bermúdez

You chose a question as your title. Why?

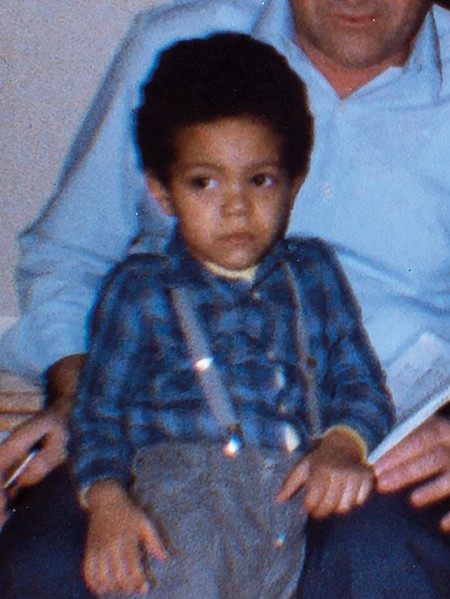

The title is a question that has accompanied me since I can remember. People have asked me where I am from, and I have answered that I am Spanish, from Móstoles. Then they ask me “Where are your parents from?”, “Spanish, too”. And then: “And you, why are you black?” It is a question for which I have not had an answer. At 30, approximately, I decided to face it through photography.

One day a black man stopped me on the street and greeted me. It is an intimate gesture that sometimes we have. He came up to me and started asking me questions and talking about everything a bit. He also asked me where I was from, and where my father was from, and why was I black. He shook me.

That same weekend I had participated in a photobook workshop and had several colleagues who had some kind of personal photographic project they were working on. I guess this was all in my head and that night I started a blog that I only knew the title of.

Photo book And you, why are you black?– Rubén H Bermúdez

Many times, the approach to the subject is in a way full of commonplaces. Your start from the commonplace that they imposed on you. Is it to take it apart or to rebuild your history?

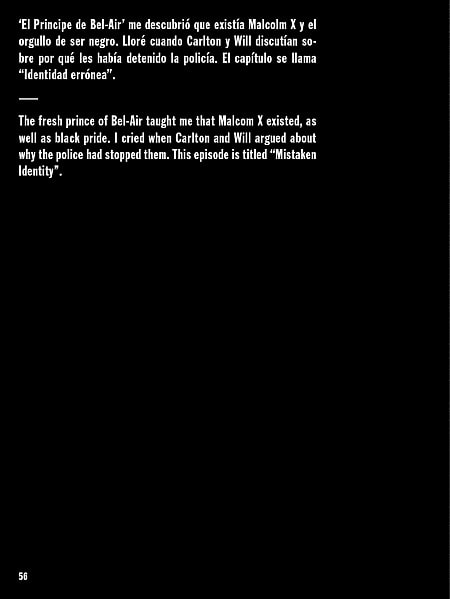

I think that, at first, I had a kind of need to tell white Spaniards “hey, Spain is very racist, why don’t you realize it?” I pointed out things or situations that seemed violent to me all the time, towards me or black people in general. As time went by, the project changed, and I tried to listen to it. I no longer wanted to speak to the white Spanish population, but Afro people like me.

I was telling my racial biography, so to speak, and I was hoping that someone would be challenged, excited, or recognized in it.

At first, I thought that I was not going to have a long journey, it was simply a relief or a personal investigation. But to my surprise, it has connected with many people. They write to me from different parts of the world and tell me “you are telling my life.” It is unbelievably pretty.

What role does photography play in the construction of racism?

As a photographer, without being aware of it, I found that all my references were from white people who explained what the world was like. The camera itself, the device, is racist. At school, they didn’t tell me about all this.

With this project, I try to turn it around. If Spike Lee, for example, thinks of cinema as a black man, what am I going to do from photography?

For example, I went to Equatorial Guinea in those years and took portraits. When I returned to Madrid, I told a Senegalese colleague about it, and he said: “very good, very interesting, but when you put those portraits on a wall, in a room, white Spaniards are going to see a poor little black man. They have, we have, 500 years of culture in the neck, and it is impossible to see it otherwise.” This still answers something of your question.

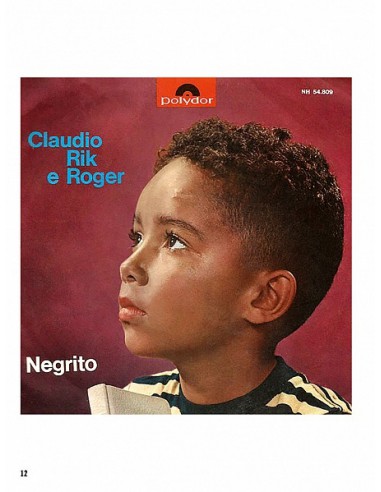

At first, I got a little angry, but I think he was right. I started working with my archive and with appropriate images, I felt much more comfortable. Let’s say that I appropriated images that were related to my biography and my blackness. And I was telling my story from my point of view.

After that, did you take pictures again?

Yes, I spent the day taking photos with my mobile. And the following year, I got a scholarship to make a movie. I liked the idea of sharing authorship: what we did was that the film’s protagonists would record themselves with their mobiles and try to build something in common.

There are many emerging artists claiming their blackness, their roots. Do you feel that it is part of a movement?

I started the project alone, with my computer and my blog. I have met other people who had organizations, associations, people who helped me, who sent me things. “Your project seems interesting to me. Look at a photo of me when I was little on the day I don’t know what” and so on. One day I received an email from Silvia Albert Sopale asking me to watch her play “No country for blacks.” I saw it, it moved me and I understood that she was talking about the same thing I was talking about, with her nuances. Now there are many more stories, it is 2021, it is time.

With mobile phones and the internet, the ability to produce and disseminate images is easier and cheaper.

Did your life change after the book?

I think I am more or less the same, but now I am older, and I teach. I also traveled a lot and, let’s say, I have recognition in the cultural context. The project has opened doors for me, and I enjoy more the things I like to do.

At what point did having an impact that is not normal for an initial project impressed you?

I felt a lot of emotion. The last year with the scholarship was harsh, I arrived with my tongue out. A kind of audience had been generated. People who felt part of the project because they were helping me. There was a group of people waiting for the book. I gave it to a couple of friends, and they liked it. We cried together. It was comforting, “at least they don’t feel upset, and they seem to like it,” I thought.

The first edition was 500 copies, it is necessary to relativize the repercussions. It does have a cultural impact and there are people for whom my book is memorable. That makes me happy. Sometimes they stop me on the street and say: “Are you Ruben?” and they remove a copy of the book from their bag.

Photo book And you, why are you black?– Rubén H Bermúdez

How do you see the future of your career?

I’m quite an amateur, I don’t feel the weight of a career either. Now we made a movie and I am looking forward to making a book about how to make a book or the creative process. I don’t have a plan about what I want to do, but things are happening and I try to enjoy it.

Narrativas Limítrofes is a project carried out with the support for the promotion and dissemination of Spanish art from: