Ipx Khüçx: World’s Disharmonies and Diseases for the Nasa people

Ipx Khüçx: Earth Burns is a project made with the support of the National Geographic Covid-19 Emergency Fund.

“We sat around the fire and talked about why we were going to the territory,” writes Jorge Panchoaga in one of his travel accounts. “We wanted to understand the Covid disease from the Nasa spiritual perspective. In this indigenous culture, spiritual imbalance with nature is one of the reasons for viruses like Covid to emerge. It is not the first time that indigenous peoples have faced viruses. With the arrival of the Spanish, the spread of various viruses was of such magnitude that it substantially reduced the native population. The Nasa have fought viruses on different occasions with their plants. Life itself is a system in equilibrium that moves between heat and cold. At either extreme is sucio, disease and death with its cold that creeps in between the bones.”

In late 2020, Jorge Panchoaga and Yaid Bolaños applied to National Geographic’s Covid-19 Emergency Fund. Yaid is a Nasa anthropologist, documentary filmmaker, researcher, and community member of the Tumbichucue Resguardo. He is a leader in his territory and has represented it in Bogotá. Jorge, an anthropologist and photographer, is a descendant of Nasa indigenous people through his mother’s lineage. Both knew about the Nasa people’s initiatives to address and prevent the spread of Covid-19. Together they planned a project to document how traditional medicine and the Nasa spiritual world comprehend a disease like covid and how they faced it.

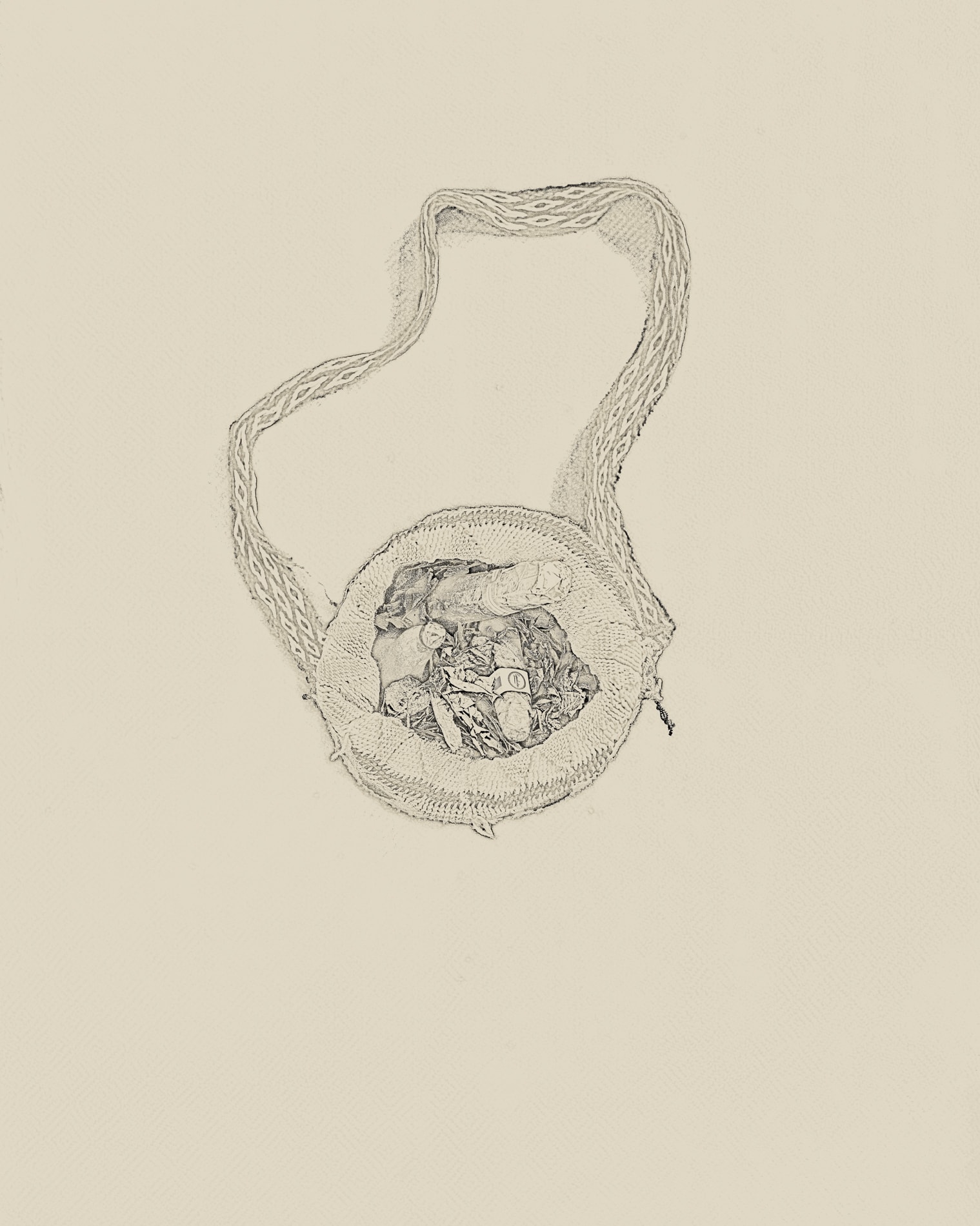

They worked in collaboration with two spiritual authorities (traditional doctors), the Thë’ Walas María Matilde Díaz Iquira and Marco Tulio Gutiérrez, and the photographer Xochilán Rojas. With the guidance of the two elders they have participated in refreshing rituals in search of harmonization. They saw Ipx khüçx, the black firefly, trapped and covered with plants of healing power. The group also searched for secret plants, toured sacred places and portrayed the dreams of the Covid fever. Together they were able to appreciate “the most indescribable beauty”, and experience the encounter with the grandparents’ time. Together, respecting the secrets of the sacred places, they developed the project Ipx khüçx – Earth burns, understanding that Nasa people don’t understand the illness of the body individually, but as a general imbalance with the Earth and nature.

What is Earth burns about?

Jorge Panchoaga: The project talks about how the Nasa community has dealt with the Covid-19 crisis through prevention and the ancestral and medical knowledge of the traditional authorities. Thanks to an investigation carried out in different areas of Cauca, Colombia, they created medical treatments to prevent contagion. One of the premises is that this is not the first pandemic that indigenous communities have faced throughout their history. The knowledge of past experiences lets the communities face the disease and the imbalance.

In the project, we entered into this knowledge of the traditional authorities, seeking to understand the dynamics of the disease as Nasa people see it. We try to portray this universe that is very complex to represent with a camera. The idea is to be able to show the other facets of human knowledge that make it resistant to viruses like Covid-19.

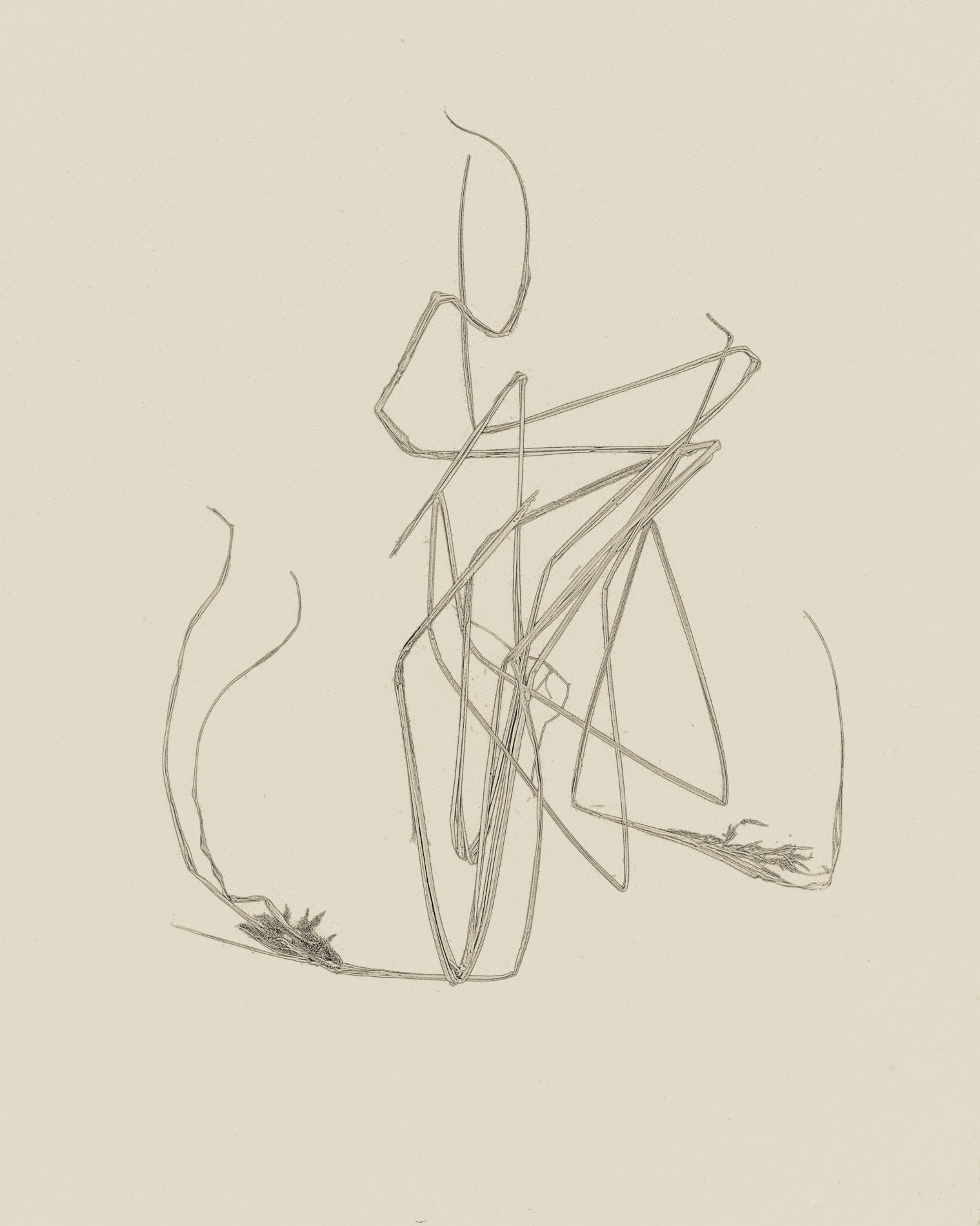

The project title, Ipx khüçx – Earth Bruns, discusses the spiritual imbalance between humans and nature. That is the work’s symbolic basis, but also the basis of the disease in the indigenous Nasa universe. Taking pictures of the spiritual world is complicated. In our case, to begin with, we did some refreshing rituals, and we investigated what people dreamt about during the covid fever. We tried to use these stories and experiences to make photos, but these images were also related to other situations. In Tierradentro (Cauca), where we were working, there are currently FARC dissidents and other armed actors that disharmonize indigenous and peasant life. For Nasa people, bodily illnesses, armed conflict, and violence are consequences of an imbalance.

Currently, we live in almost twelve departments of the country. The displacement of people has been caused by different factors such as armed conflict or natural disasters. We think of it as the existence of disharmony and imbalances. In the community, it is known as the sucio, the dirty. It is a disease that is both in the territory and in the lives of the people.

These insects appear very early in the morning. When we were doing the ritual, one of these insects arrived flying. The elders captured and enclosed it with medicinal plants and placed it strategically to appease its evil and deadly energy. We could take pictures in some moments, not during the ritual, but walking with the elders afterward. The images show the environment, characters, spaces, plants, and territory at night and during the day.

The Thë’ Wala treats Covid as that external sucio that has come to the indigenous and peasant communities to affect the forms of social relations. But also the relations with the supernatural powers, which ultimately regulate and protect the lives of indigenous peoples, especially the Nasa people.

For this project, it was essential to start by talking with the elders, with the Thë’ Walas with whom we were able to work and take into account the darkness. The ritual work of harmonization is always done at night because it is precisely when the sucio appears in the form of ipx khūçx or black firefly. It is an insect that has a bright light, it’s like a spark of fire. The firefly is the representation of illness, imbalance, and disharmony. It also represents the future, both in positive and negative terms, of the person or the community.

There are five authors in this project, in addition to the two of you: María Matilde Díaz Iquira, Marco Tulio Gutiérrez, and Xochilan Rojas. How was the teamwork? How did you think about the images? How did you distribute the work?

Yaid: First, we consulted with the political and administrative authorities of the Cabildo of Tumbichucue. With their authorization, we began to talk to the two elders with whom we worked. At first, they did not want to participate. But finally, they have understood the importance of sharing what they know with the new generations. What they have shared is part of the memory, not only of them but also of other spiritual authorities who continue to do their work in the moors, lagoons, hills, and mountains.

With the arrival of Jorge and Xochilan, I believe that the energies allowed us to have a confident relationship. It is a collective work in which we all contributed: the elders with their wisdom, systematizing the information they offered us and translating a good part of what we discussed. They were very emphatic in saying that not all the images captured could be shown, so together, we chose which ones could be.

Jorge: The two eldest who worked with us are Yaid’s uncles. From the beginning, we were all told to call them uncles, especially if we met an armed person. There was a dense atmosphere. We all knew that things were happening.

Each of us took on tasks very organic in a particular fieldwork. I got sick, I had just seen my grandmother a little sick, Yaid had work to attend to at the Cabildo. Two people were killed on the road a few hours after we arrived. The pace was slow. We always waited for authorization from the elders and could only take one photo of the ritual. So we looked for ways to extend the project, taking into account that photography has limitations and that at that time and in that context, the camera was suspicious.

When you talk about disharmonies or imbalances, you put on the same level the emergency caused by Covid-19 and the armed conflict and its effects.

Yaid: A series of signs appeared when we were doing the ritual. A cloud took the shape of a coffin, and the Thë’ Wala interpreted that this was a symbol of death, that someone was possibly going to die. Then other signs appeared: a motorcycle crossing the road late at night. We thought that maybe the cloud was announcing the murder of a community member.

The next day, while we were working on the project, Jorge’s grandmother died in Popayán, and cases of forced recruitment were seen in the territory. The elders explained to us days later that the signs also indicate various adverse situations experienced in the community. We understand these situations as social disharmony, and illnesses. The elders also call them sucio.

Jorge: the sucio is, as Yaid points out, a reading of nature. It communicates through spiritual energies and signs that the Thë’ Wala interprets. And this is not only the disease as a bodily symptom but also the daily events of the community.

The balance has to do with the individual and his body, but that body is part of a context, territory, community, and humanity. In this sense, harmony, illness, and balance go beyond the individual being.

And now let’s talk about the project title that you are also turning into a book. In english, it is Earth Burns. In Nasa Yuwe it is Ipx khūçx.

Jorge: When we were in Tumbichucue Yaid told me that when the Earth is out of balance, it spews black ash because it is burning. I wrote that down, and days later I asked him and he gave me a name that is Ipx khūçx, I related it to the Earth. That idea caught my attention because it is the symptom. When there is an imbalance, the Earth expresses itself in that way. To take care of that situation, the Thë’ Walas do the rituals of refreshing.

Yaid: Ipx khūçx is the insect that carries the sucio, the dirt. When it appears, it can make people sick and even cause the territory ill, so the Earth enters a state of imbalance. It gets super hot and needs to be harmonized. To do this the Thë’ Wala must spray it with medicinal plants.

When the Earth is like this with a lot of burning, diseases such as Covid can appear, and different community diseases such as social conflicts. It has deep roots that we do not fully explain in the book.

Jorge: Also because photography cannot explain it, it has some limitations. That is why we have included some texts.

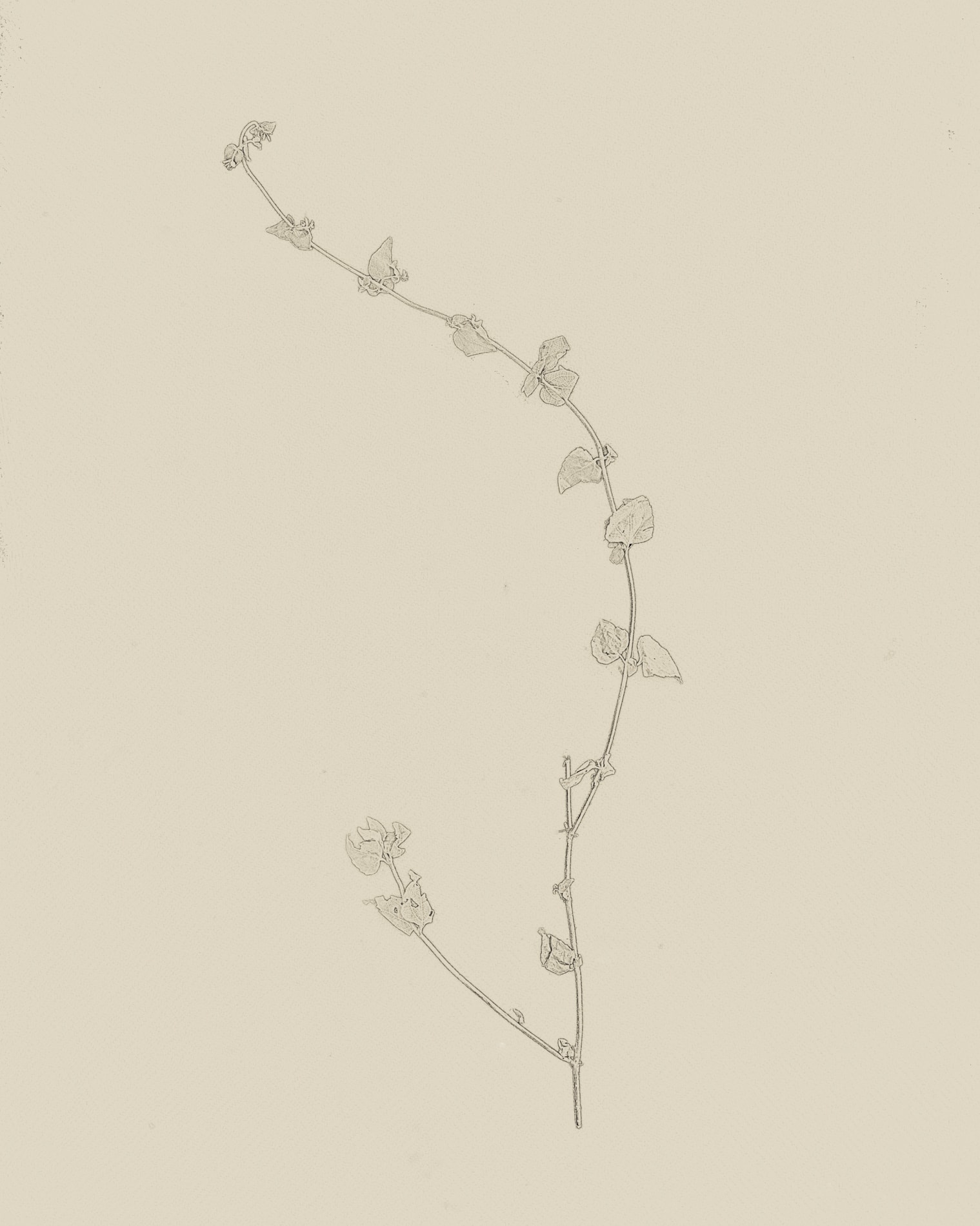

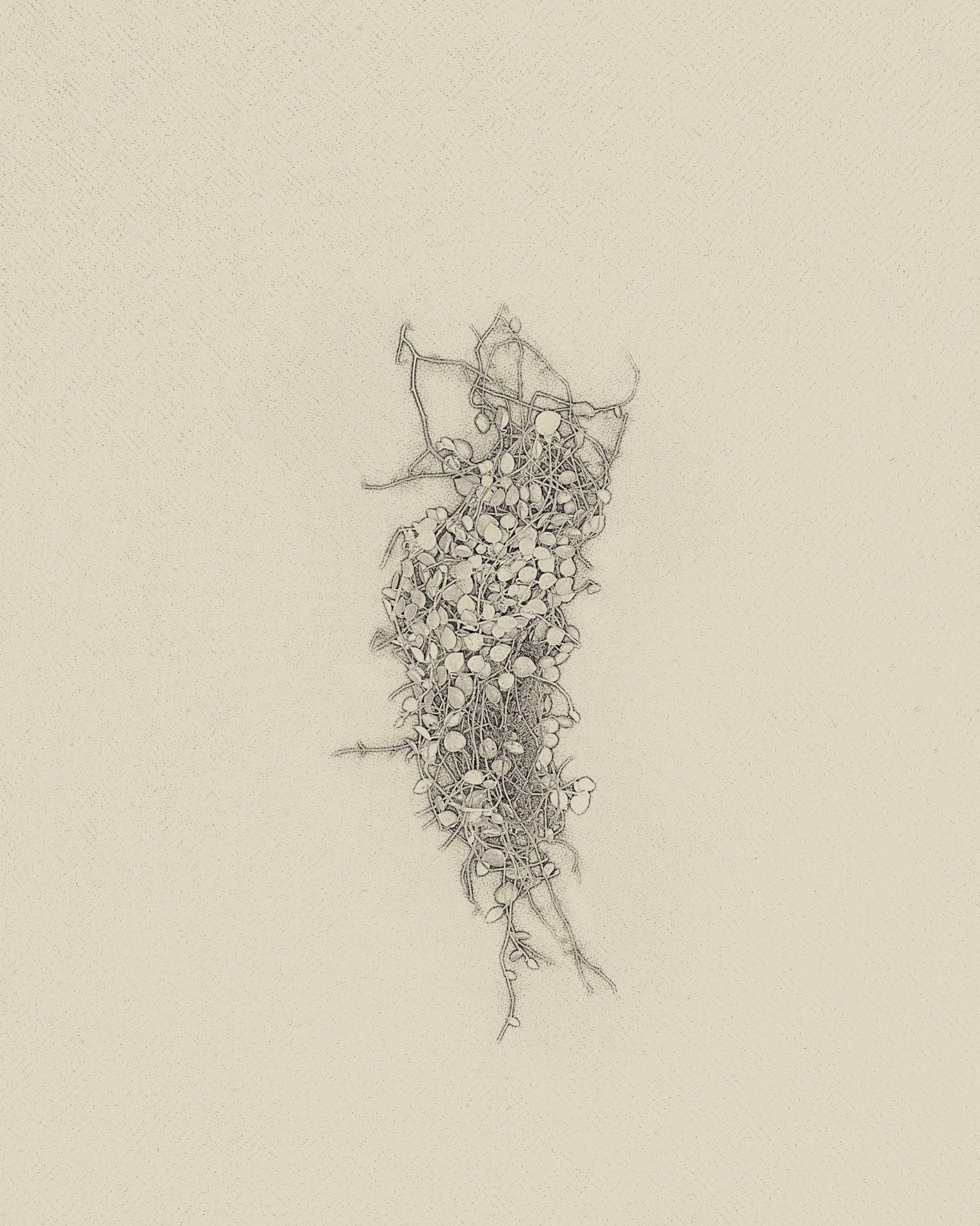

Two of the book’s texts caught my attention, and they are related to plants. One of them says that plants are the bridge to the time of the Earth and the ancestors and the other states that plants are the most indescribable beauty that human eyes can see. How is the relationship between beauty and the time of the ancestors?

Yaid: The encounter with the plants is of such incredible clarity and beauty that not even they, the Thë’ Wala, can describe it. For them, the beauty lies in the fact that some plants can cure illnesses or ailments. It has to do with the power and strength of the plant.

The Thë’ Wala said that we are always in contact with the elders through dreams. They carry and preserve the knowledge of the Nasa people. The encounter with the ancestors has to do with the ksxa’wesx, that is, the visions that indicate what to do, how to walk, how to heal, how to collect the plants, and how to prepare them. We cannot see them, but the wise ones can.

Jorge: this also has to do with some reflections that have caught my attention since I was working on Dulce y Salada. I am interested in the relationship of the human being with the Earth, with geological time, and it has to do with the fact that there are many times and time scales in the universe that run in parallel. If we think about it, the geological or universal time scale is almost incomprehensible for human beings and the short time we live in.

We as a species have generated hundreds of ways to understand, manage and relate to these scales: physics, numbers, literature, and so on (on the Western side). However, all peoples have sought how to connect with those other times. The rituals of each culture are bridges to connect with other times, different knowledge and other dimensions. Rituals are a way to comprehend how we relate to what is more significant than us as a species. Plants, in many of these places, have been the vehicle –coca leafs, yagé, and peyote are ones of them. The communities create a link with the spirit and energy of the plant. One learns to travel to other times with it, and together with them one learns. It is in the time of the Earth where the Nasa elders live, where the foundations of the universe and the Nasa people, the grandparents are the rocks, the mountains, and one speaks with them through the plants and the Nasa yuwe, their language. They inhabit another time, and they communicate with ours which is much shorter and more volatile, for that there are channels.

One of the ideas of the project was to take photos based on the dreams that some people had during the Covid fever. How did that happen?

Jorge: It was something that came up during the fieldwork. The projects take on their rhythm, their own life, and they dialogue with you. Sometimes you have to force them, but sometimes not. We didn’t plan this dream thing. It came up there and was an exercise of asking and listening. Without realizing it, there were images related to that at the end, but it was not something planned.

Yaid: the dreams always indicated that something was happening. Animals were always appearing. In our cosmovision, these animals came from the origin. They announced that if not treated properly, this could lead to death. Other beings also appeared, such as birds, which, according to the Nasa people’s beliefs and oral tradition, are the messengers of life. They would go through dreams indicating what to do, what to drink, and even what to eat.

Interestingly, there is a woman Thë’ Wala. I understand that it is not so common.

Yaid: People commonly recognized them as midwives but also as great pulse takers, that is to say, people who take the pulse, especially of children, to identify possible ailments. They are also sobanderas. In these three trades, they use medicinal plants.

Mainly, in the case of Tumbichucue they have always existed, but the women have been more reserved. They almost do not manifest all the powers, and knowledge they have. It happens mainly because this is a macho society. However, breaking those paradigms, they have begun appearing in the public space. Investigations of the communities shows that women’s knowledge is much more potent in terms of the use of medicinal plants. The Thë’ wala formerly transformed themselves into animals to trance into the space where the first wise men of the Earth dwell on asking for advice that allowed the healing of the different disharmonies on the Earth. They lost this power, but they are here, and we must value it because they are the root, the origin of life, and of all the processes and ties with nature and humanity.

Yaid, you have talked about the importance of sharing knowledge. In that sense, what is the role of this project?

Yaid: This project is an exciting bet to show the richness in the indigenous territories related to the encounter with nature and the wisdom of our elders. This type of project is necessary to present research’s importance to educational institutions. Getting together with the elders to write and preserve all their knowledge is essential.

In addition, this project has made it possible to sensitize the elders’ hearts, so they also understand that sharing is vital and must return knowledge to the community. It is also an excellent example of getting out of the talking and starting doing things. It is an essential gateway to knowing the wisdom of the Thë’ Wala and the wisdom offered by medicinal plants.

Finally, Edilma Pumba, an indigenous woman from Çxhab Wala (ancestral territory of Vitoncó), participated in doing the translations from Spanish to Nasa Yuwe in the texts of the book. Ipx khüçx – Earth Burns vindicates the knowledge and wisdom of our Thë’ Walas but also promotes the strengthening of the rituality and practice of the mother tongue as the source for the preservation of the oral tradition. The book shows a sum of vital elements that, perhaps, we have been leaving aside for believing that other cultures are better than ours.

Why did you decide to make a book?

Jorge: For us, it is a way of returning some of the work to the community. Whenever I make books, I try to bring them back to where the work has taken place. We will invest part of the surplus from the book’s sale, buying equipment such as a camera, a computer, and a recorder machine for the school of the Resguardo. We want also to do photography and oral memory workshop so that they learn to tell stories with images and audio.