The juanes are balls of rice, chicken and hard-boiled egg, seasoned with turmeric and wrapped in a tamale. The tacachos con cecina looks like fried plantains and have salted pork. The suri is a yellow worm that is grilled. Eight years ago, when the Peruvian chronicler Joseph Zárate began traveling through the Amazon rainforest looking for stories about environmental leaders, social conflicts, and extractive industries, he realized that in the house where he had grown up, he was eating lunch it was food from the jungle.

Why, then, did his grandmother not talk about her origins, her birth in the indigenous Kukama Kukamiria community? Why did she say she was ashamed? Why did she didn’t tell him about her childhood in Pucallpa? Moved by these intrigues, as he progressed through chronicles that won him awards, in parallel Joseph interviewed his grandmother.

“I understood that to survive in the city, she had to acquire the behaviors of the women of Lima. Peruvians and Latin Americans in general, have constructed our identity in such a way that we place the Western in front of the indigenous in a position of superiority, and, in order to achieve that status, many times we have to give up who we are,” he reflects.

And it is that, when he is not producing a note, Joseph travels almost infinite roads inside his head. He flip the ideas one way and then the other. He is never sure what “the truth” is and he turns it into a virtue. “I am like that, what wins is the permanent question”, he says. So, when he writes, he manages not to escape complexity, the tensions, the contradictions that the world around him is made of.

Besides the inward questions, Joseph seeks to tell stories that disturb and provoke a reflection around the impact human decisions have on nature and on the lives of others. That’s what he did, for example, in “A child stained in oil ” a chronicle that won the 2018 Gabo prize. There he tells how after a spill of 500 thousand liters of petroleum in the Amazon, the Petroperú company paid to the members of the Awajún community to manually clean the fuel from the river, risking their health and their future.

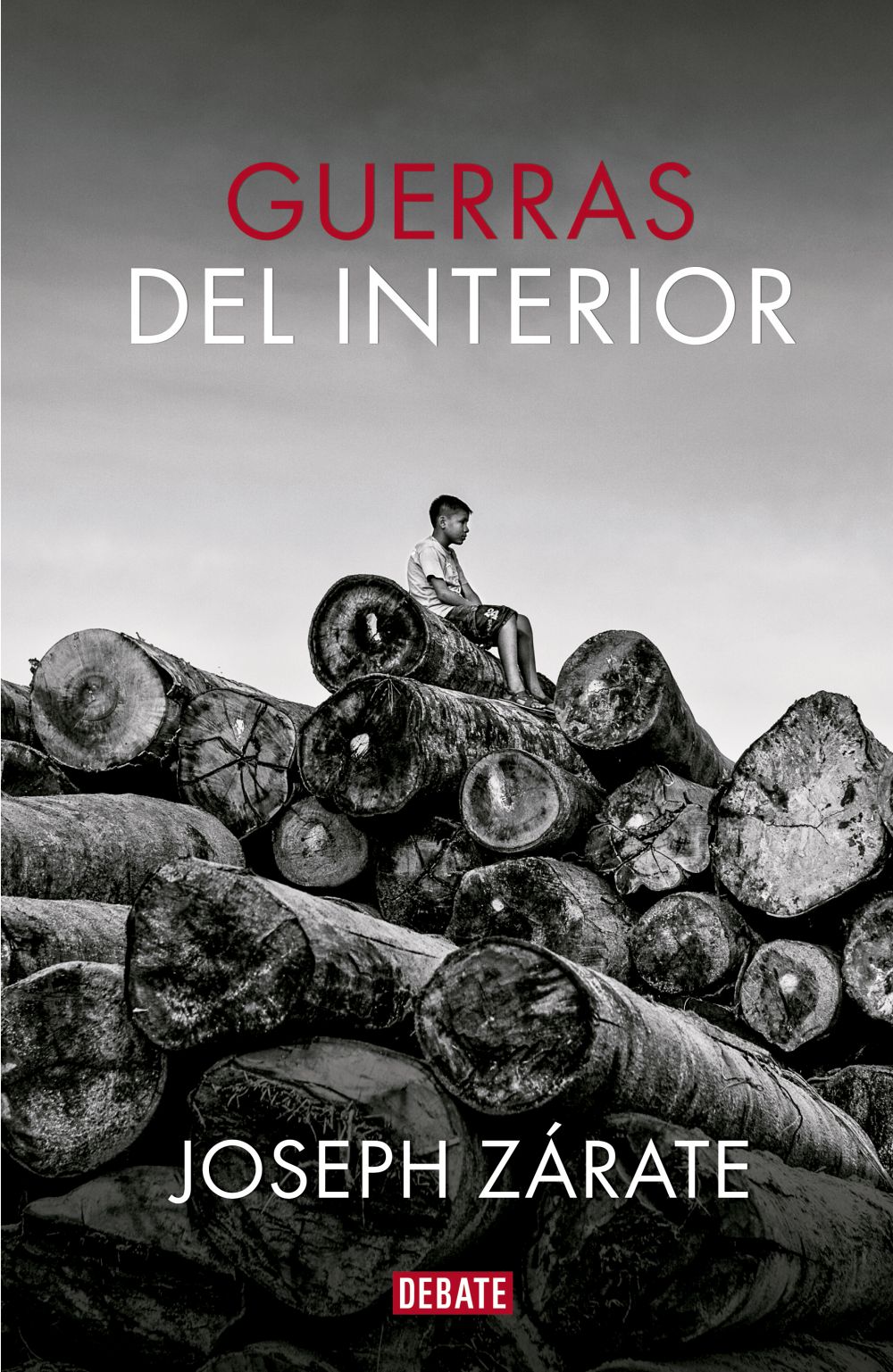

A similar alchemy, between his own, the collective and the identity, achieves in his book Guerras del interior. It was published by Debate and won the 2016 Ortega y Gasset prize and the 2018 Gabriel Garcia Márquez prize. “I feel that it has been a journey from a geographic outside to a more emotional inside . That is why the book is called like this: there are conflicts inside the country, for resources that are taken from the inside of the earth, and that challenge my own self” he says. Joseph is a journalist who wants for the stories he tells, the same as for the planet: not to make a use it and throw it away.

Some of his texts are part of the Atravesar Amazonia project, a platform that seeks to communicate with diverse resources what happens in the Peruvian jungle, home to 33 millions of people and the habitat of thousands of species. One of Joseph’s stories on the site, portrays the ecosystem degradation by the overexploitation of resources.

“When their women begatn turning their backs on them in bed and left them without sex for not bringing enough food to home, the Kichwas from Tigre river discovered the climate change. It wasn’t that they had become less skilled with the shotgun. What happened was that the jungle around them, the same one they thought they understood, had become incomprehensible”, the chronicle begins.

Why did you choose that start?

The story is about some Kichwa hunters who live on the border between Perú and Ecuador. What happened in their community was that, because they didn’t have a control over how many animals they hunted, they had been preying on the fauna. Forest loggers had deforested and global warming and droughts were exacerbating the situation. There were fewer and fewer animals to eat. As a chronicler I’m always looking for the beginning of the text. And I realize that I have it when a scene makes me feel something: laughter, sadness, anger. That, the reader probably feels too. We are animals that run under emotions.

How can the questions that arise from particular stories be universalized?

For me, writing over socio-environmental issues is not writing about the ecological, but reflecting about some aspects of the human condition. Telling about our relationship with nature is the vehicle to discuss our idea of progress, what it means for us to live better, who we are, how we relate to nature and to other people. How far can our inclination to vanity, to power go ? I try that this local stories can make a Russian, a German, a Spanish, a Mexican, an Argentinian reflect about it.

How do you choose what to tell?

What I feel is that I write about matters that have some emotional connection with me. One of the reasons I started to explore the jungle has to do with the urgency I have to know my own country and my personal history. The beauty of journalism is that, beyond offering me a way to show reality and to denounce injustices, it can be a journey of self-knowledge. It makes me value my family’s origin, and there is something of introspection: there are no journalistic questions, there are existential questions.

How do you run away from the common place, the cliche?

When you find out about a petroleum oil spill in the jungle where families and children are becoming contaminated, the first thing that appears is something that revolts you. The force of reality, the historical neglect by the State on indigenous peoples is so brutal that you cannot help but be outraged. But after that rage, that anger, an attempt to understand why, appears in me. Also, I wonder what this means for me as a citizen, as a Peruvian, as well as for the people who have suffered it. The chronicle allows you to ask yourself those unknowns without being a prisoner of the deadline.

What does spending time in the territory contribute?

To answer all those questions about why what happens, requires an arduous fieldwork. I decided to invest months, travel three times, and interview more than 60 people. When I try to go to those areas of the country I stay for a while, I stay with them to reflect. I seek to understand why they do things, what impact their decisions have on their emotional life.

Why tell stories?

I think we become journalists because we have a sense of duty, that society can be more just. I recently worked in a funeral home for a chronicle on deaths from Covid-19. It was a very painful experience, to carry corpses, go to the crematorium, distribute ashes. I tried to tell all that I experienced and asked myself again: why write about this? Why add more pain to the pain? It is a question that you can apply to all journalism: why tell more terrible stories? I feel that, to the extent that we tell journalistic stories with commitment, respect and empathy, I retain the hope that something can be changed.