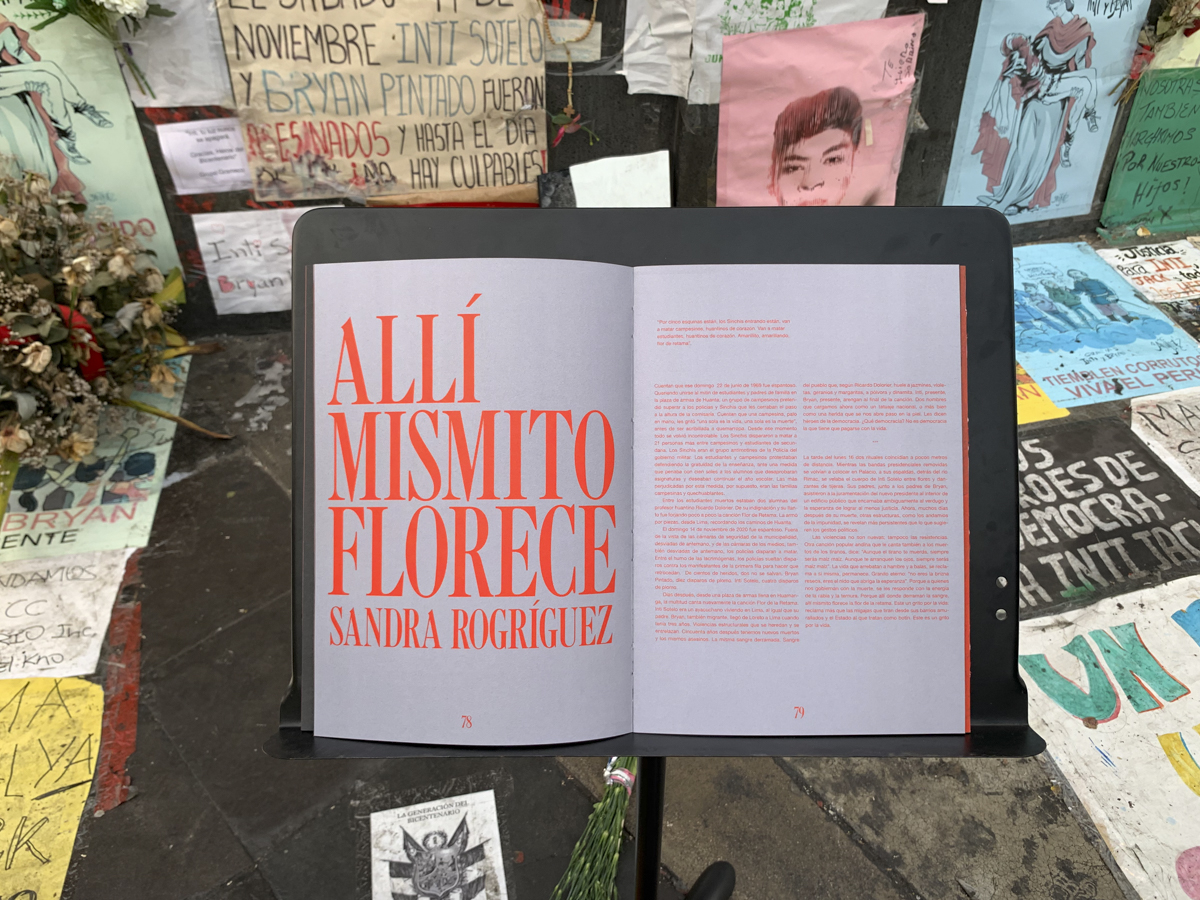

“On the afternoon of Monday, November 9, a coup d’état was consummated in Peru in the midst of the economic and health crisis”: this is how 11/20 begins, an urgent book. The prologue is written by the anthropologist Sandra Rodriguez who, together with the photographer Musuk Nolte devised a hot collective publication, to gather images and stories that tell of the repression and the crisis that crosses the South American country. The book can be viewed online here.

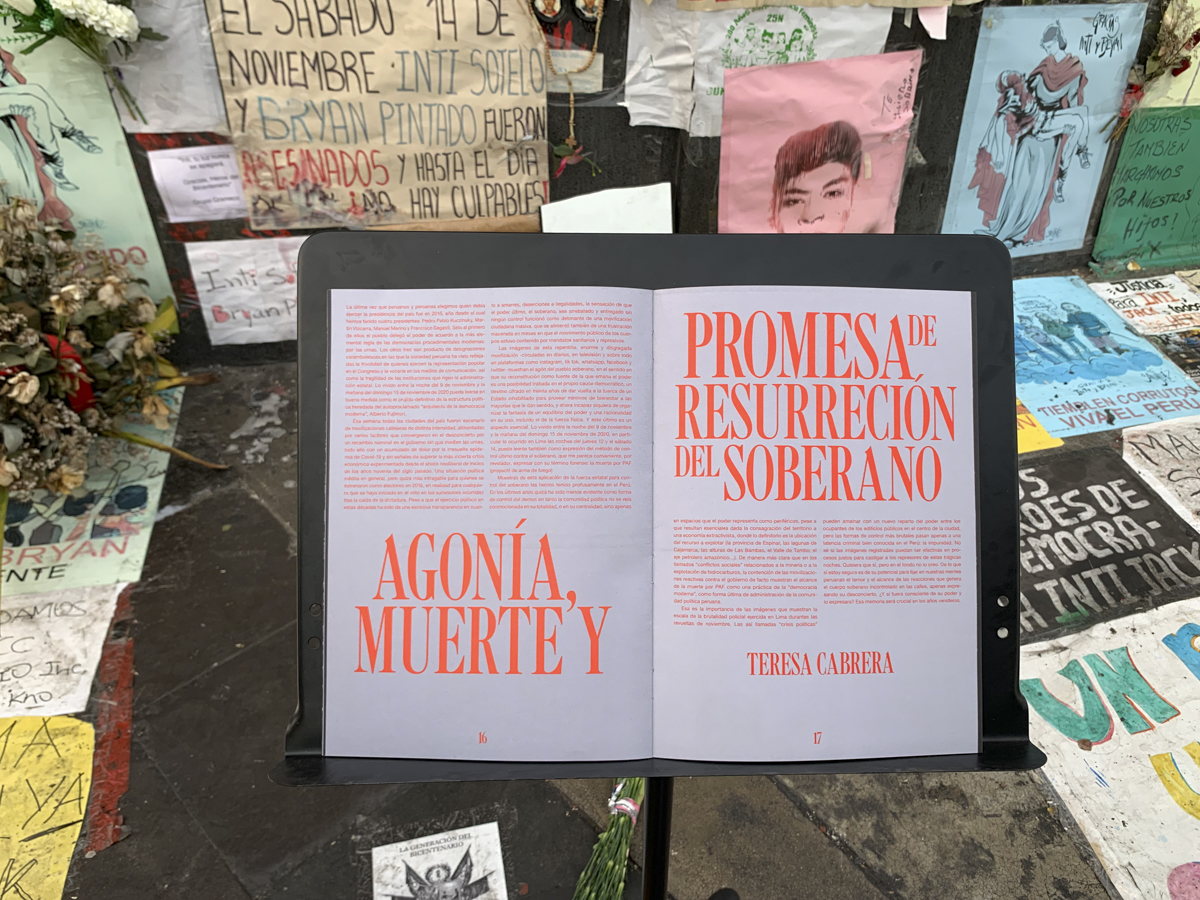

The mission, Sandra says, was to publish the book “when outrage was active, when we could capture that emotionality”. She insists that it is not a job to represent the past but to continue to intervene in the present. “It is an effort born out of mass outrage. It’s the idea of making space for those emotions that arise, rather than starting to make a diagnosis and turn the page,” she says.

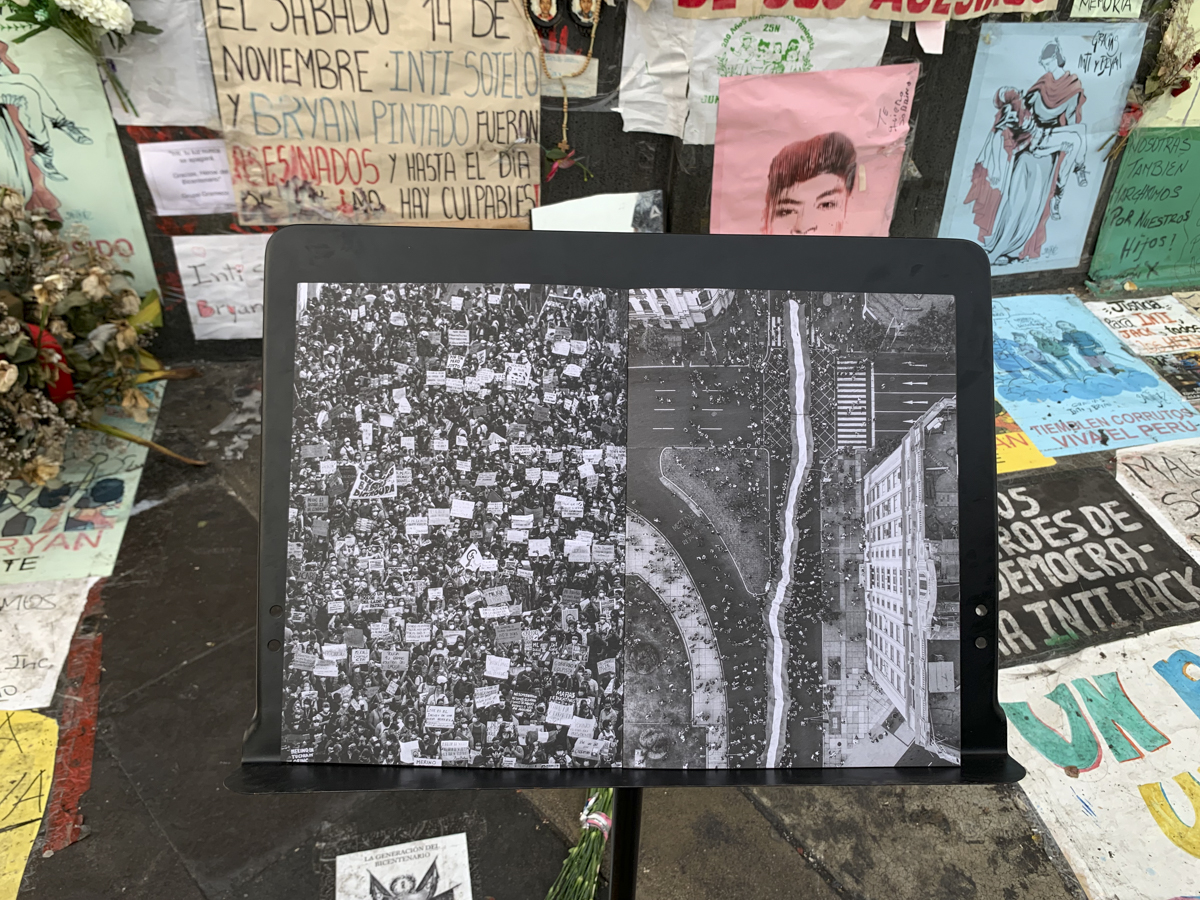

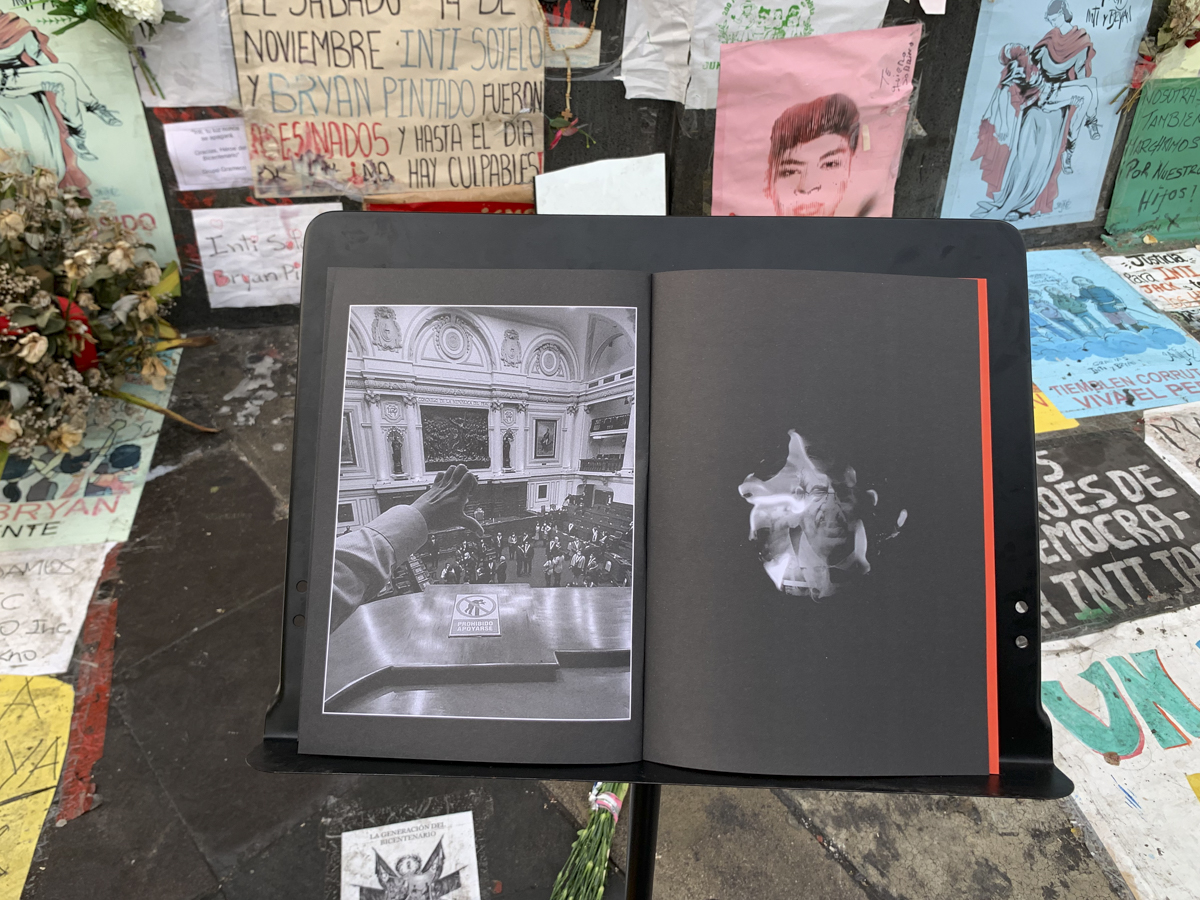

The mobilizations throughout the country as a result of the dismissal for “moral incapacity” of Martín Vizcarra and the subsequent assumption of him as interim president of Manuel Merino marked a milestone in Peruvian history. It is estimated that almost 40 percent of the population participated, in one way or another, in the protests. Sandra explains that it is a complex manifestation, in which various discourses, interests and social classes converge. Right now, there are many meanings in dispute on the Peruvian streets.

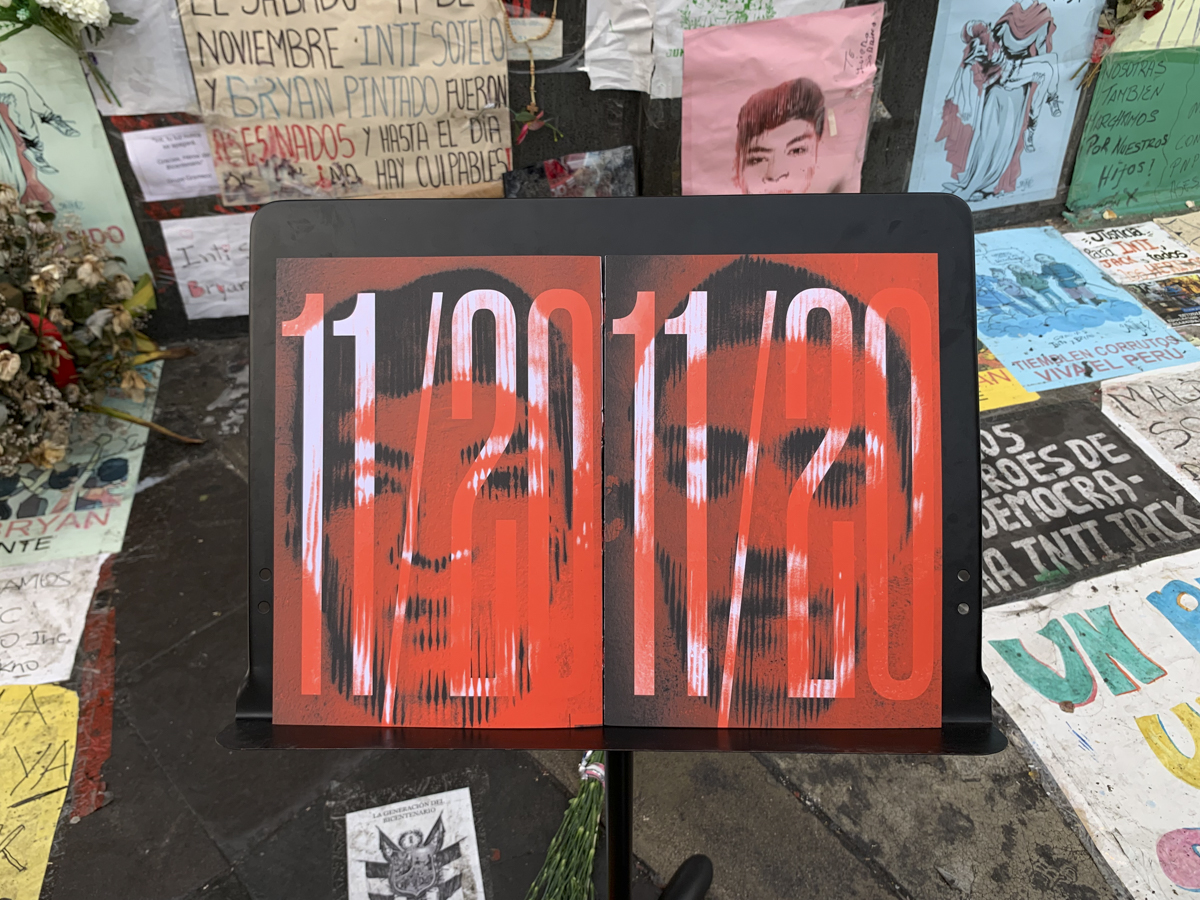

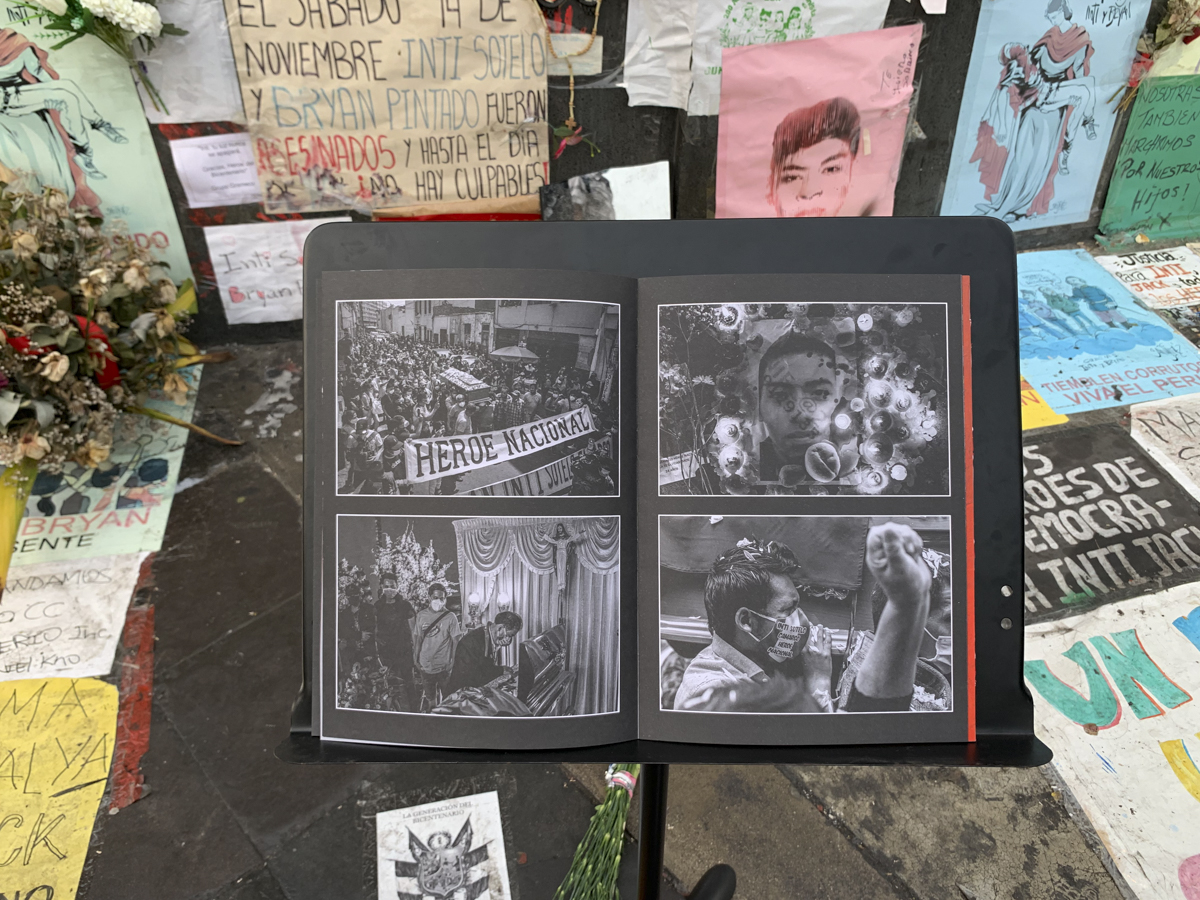

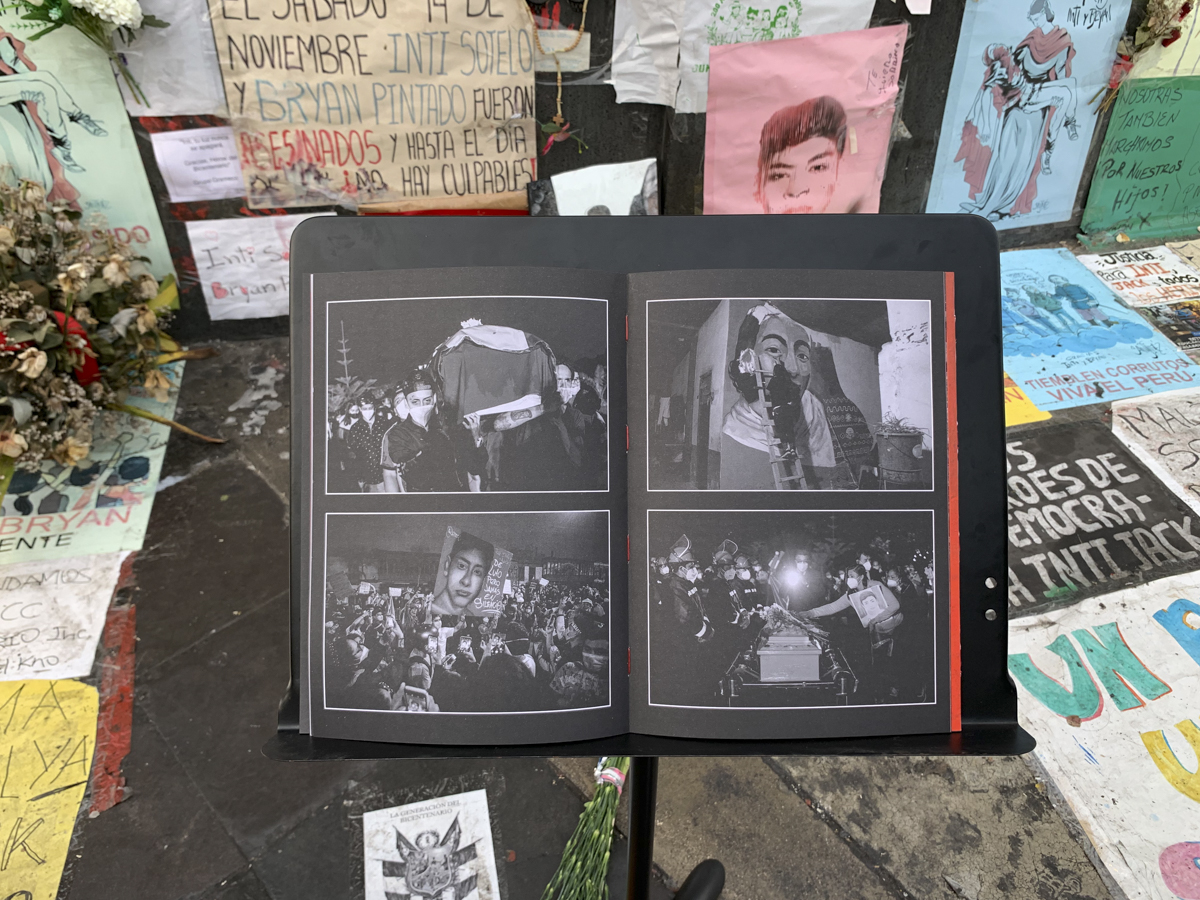

Merino resigned a few days later, Francisco Sagasti took office. Although the crisis was contained with that fact, many of the issues it brought to light are still alive: the “bicentennial generation” and its significance, a broken party system and several murders still unpunished. Like that of Brian Pintado Sánchez, who was 22 years old or Inti Sotelo Camargo, who was 24 years old. Both were fatally injured by multiple shots of lead pellets.

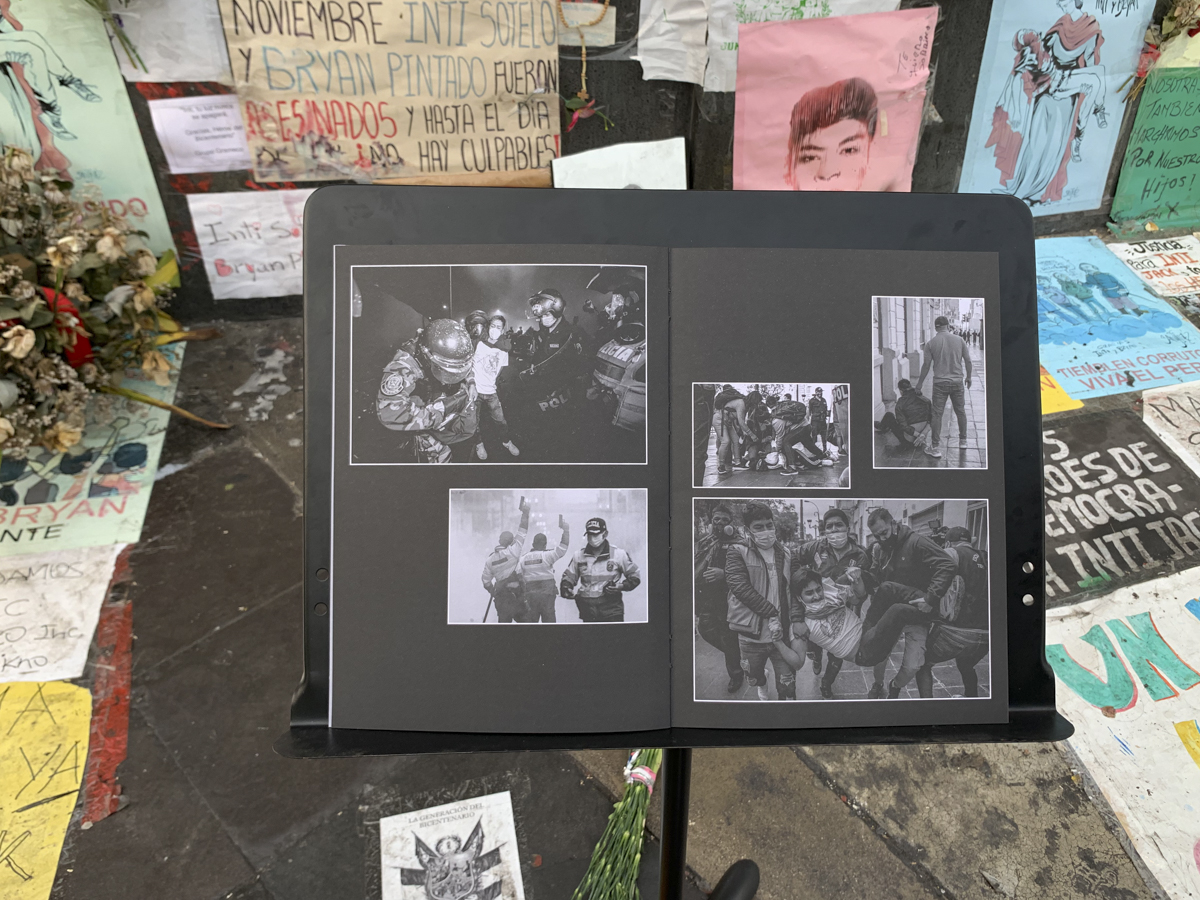

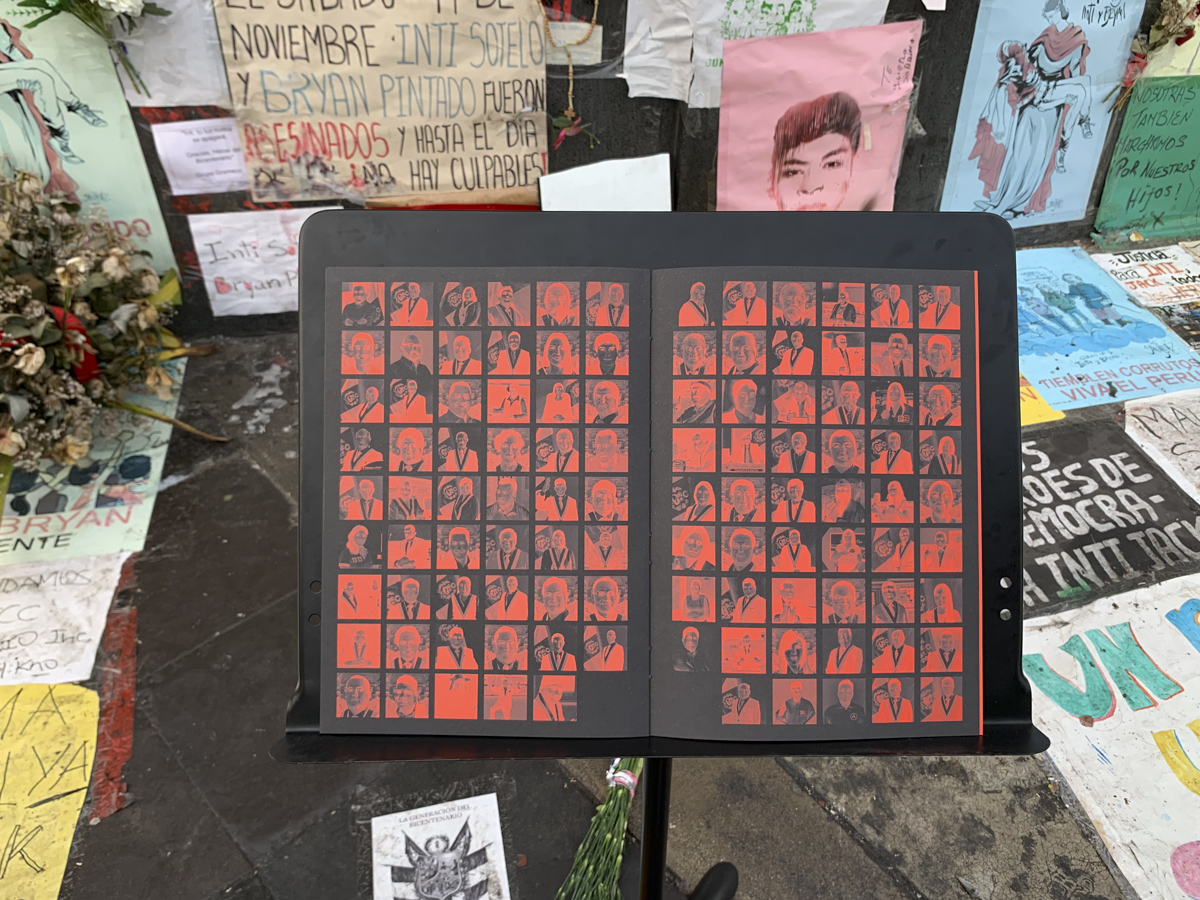

For Sandra, the deaths of Inti and Brian precipitated the absolute collapse of the legitimacy of the de facto government. In the book, she highlights “the level of police brutality captured and shared by independent photographers and ordinary citizens.”

How do you put together a collective book?

Musuk’s role and mine has been to devise and coordinate, fundamentally. We think of authorship blurred in the idea of the collective. There is a fundamental week, from November 9 to 15. On the 15th, [Manuel] Merino resigned and the uncertainty of who was going to take over remains. Until the 16th there are quite a few protests. In that week, Musuk came up with the idea of starting to organize this kind of collective archive, since it was very clear what role the images that were being produced by independent photographers were playing.

There was a lot of production and circulation of images and that not only made them share, but also created a particular emotionality when seeing images of police violence: they were essential for people to feel more indignation. All of this makes it very clear that Merino could not continue in power.

Musuk comes up with the idea, launches the open call from his KWY publishing house for photography. The deadline was November 30. A few days later he invited me to participate to put together the texts. There we thought about some issues that we did or did believe should be addressed in this publication: among them were police brutality and the bicentennial generation.

It was suggested that these mobilizations made the emergence of this new actor visible, the so-called “bicentennial generation”. What does it mean?

The label arises from people who protest but also ends up being co-opted by more official speeches. Not right now, but at that time it was highly disputed. It was very strong: Peru celebrates its bicentennial of independence the other year, so for two years they have created a body that is in charge of organizing certain celebrations and emblematic works to inaugurate at that time. Let’s say that, up to that point, the subject had been addressed only from the official speech.

The denomination arises, then, in an effort to question this celebratory but half-empty official narrative. We are celebrating a “half republic”. The bicentennial is not what the official discourse tells us but the citizenship in the streets.

Soon, due to the situation, the mobilization had a lot of popular support according to the polls. More than 70 percent of the population was against the coup. The media begin to use it as a slogan. When Francisco Sagasti took office he changed the name of the scholarship “President of the Republic”, he made the symbolic gesture of changing it to “generation of the bicentennial.” Some conservative right-wing newspapers begin to speak of the “bicentennial generation”, they begin to make the commercial profile. It was very well taken, José Carlos Agüero tells it in the book: the idea of the bicentennial generation has an anchor in the old.

It is quickly used in the most condescending speech, which celebrates the youth: “oh, the young people, who teach us,” they say. Although the bicentennial generation creates the idea of an interlocutor and gives a face to the people who are protesting, at the same time it dilutes that it is a complex demonstration in which there are many speeches, several social classes with different interests and that not all they came out to defend democracy with a civic ideal. There are also those who came out with a more visceral indignation, against everything that power represents, even the very idea of democracy. There is this whole dispute of meaning.

It is interesting to think that the mobilizations were not only in Lima, the capital. Did the dissemination of the images play a role in this process?

There are many images that, in reality, are photographs of the messages that circulated on the banners. Matheus Calderón tries to analyze how the messages circulate, how it circulate in the protest. How it has the double life of inhabiting the street and also inhabiting the internet.

It seemed important to us to include stories from regions. It was a huge mobilization at the national level: some three million people have been on the streets simultaneously in various parts of the country, even in very small provinces. While we were talking, the peculiarities of each place came out. I was struck by the text about the Loreto department by Norma Rivas. When Inti and Bryan died, on the 14th, national vigils began to be organized in their honor. In Loreto, a tribute was paid to them and to the victims of the Covid. That speaks of how equivalence is created between the victims of the conjuncture and the victims of a much more structural violence, which affected during the pandemic due to the absence of health services. There are very terrible images of May, June: the corpses piled up in the hospital. It seemed very particular to me that both types of victims were honored in a single space. In the department of La Libertad the protest was also massive. The boys say: “I have never seen so many people protesting in my city.”

I believe that the idea of including texts of analysis and more testimonial texts is fulfilled. I feel like the post is a bit liminal. It is something that takes place in the middle of the protest and we wanted to get this out of hand, when the outrage was active, when we could capture that emotionality of what we are experiencing. The publication inhabits this liminal space between active indignation and this look at what has happened, inhabits both spaces. In that sense, I think, it also fulfills its function.

I emphasize that this is not a text to represent the past but to continue intervening in the present. We don’tt mean “this happened”, it is not an academic effort. It is an effort born out of mass outrage. It is the idea of making space for those affections or emotions that arise, making space for that to expand before starting to make a diagnosis and turn the page.

At what point is Peru now?

Definitely, we are no longer in the hyper optimistic look that was filling the common senses. When Francisco Sagasti took office, speeches such as: “we have recovered democracy” or “these young people no longer remain silent”, “this generation is going to change the country” are created. I believe that, weeks later, several simultaneous social outbreaks, protests by unions, mining companies, breweries, multiple protests throughout the country began. The most important was the agrarian strike in protest of the workers of agro-exporters. What they were paid was a pittance.

The specter of terrorism was quickly raised to delegitimize the protest. The repression has been very strong, they killed a boy in the north named Jorge Muñoz, we also mentioned him in the text. We were in perplexity to see how everything returned to normal.

However, I think that November has been an event that marks something strong in the political culture of Peru. I have friends who have taken to the streets for the first time, and that can change how other protests think in other parts of the country. I think the key is this awareness of what citizen power means.

Beyond that, I feel that Peru has a very solid scaffold of impunity for crimes committed by the police. More than a month has passed and there is no person responsible for the deaths of Inti and Bryan, which is one of the main demands that remained from the demonstrations. The State has been able to create a fund to support the victims of the mobilizations. But we are at the moment when you realize that violence and impunity have a history and are deeply rooted in the structures of the State. It is a moment of realism, after that first wave of optimism.