Steal audio and animate it: that character will tell you the truth

In the project Animaciones Salvajes, Martín Ameconi borrows audio from rock stars such as Lou Reed, David Bowie, or el Flaco Spinetta, and creates small animated prints that explore the meaning of life. His creations test the possibilities of animation in the context of a popular culture dominated by archive fever.

By Alonso Almenara

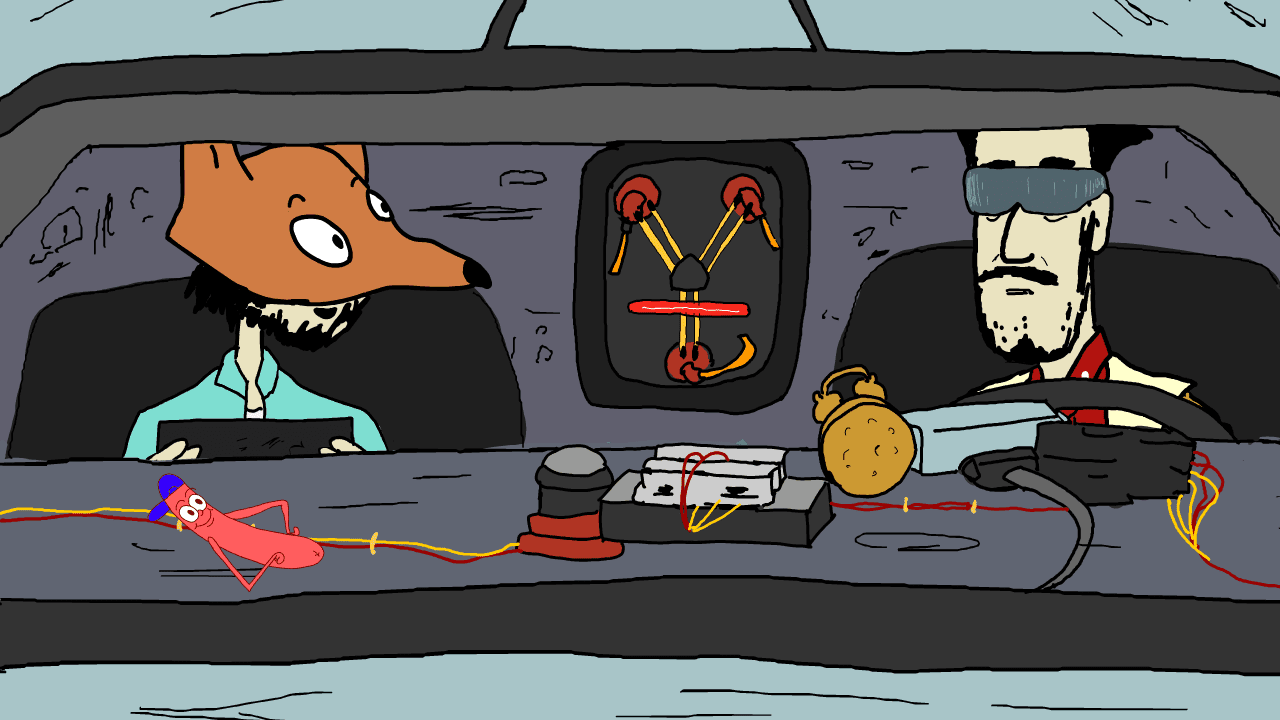

That’s what Animaciones Salvajes is about: it’s a series of animated shorts that imagines what would happen if you got all these wonderful people together in one place and made it up. And the more mundane the situation, the better.

The project was created by Martín Ameconi, a 36-year-old Argentine musician and illustrator born in the city of Marcos Paz, in the west of Buenos Aires province. You can follow him on Instagram y YouTube, where his profile picture shows him mysteriously decked out in a fox mask.

His first animations came in the classroom: at that time, he made them in his notebook. Later, as an adult, he made them with his cell phone, as if he were playing. Little by little, his experiments found a defined aesthetic. In the videos he posts on social networks, Ameconi uses audio of interviews with rock stars and combines them with a visual style made of recycled elements of pop culture: soccer, the Friends bar, and the Simpsons characters.

Between melancholic and surreal, his short films are followed by nearly 40,000 people on Instagram. This fan base includes musicians who are portrayed in his clips: this is the case of Fito Páez, who collaborated with Ameconi to record the voice for a special episode of Animaciones Salvajes, or Andrés Calamaro, who commissioned him to make a video clip for the song “Pero Igual”, included in the re-release of the album Honestidad Brutal.

The clips are delirious. Some are made in jest. But most have a humanistic tone that seems genuine. It’s hard, for example, not to feel something in your stomach when an animated version of Charly García expounds on the intricacies of creation.

How was the Animaciones Salvajes project born?

The project started in 2020, in the middle of the pandemic. In Argentina, we were confined, so I had much free time. And one day, out of boredom, I started looking for apps to make animations. I used to do it when I was a kid. I used to draw and liked to animate characters with my notebook, turning the pages quickly. I did it more or less well. Until I met music, and I dedicated myself to that.

But it wasn’t possible to do many concerts during the pandemic either. So I thought of alternatives to occupy my time that had nothing to do with work because my goal in life is not to work. I downloaded an app called FlipaClip, quite limited by the way, to make frame-by-frame animations with my cell phone. I downloaded it with the idea of playing to remember what I used to do as a kid and see how I could do the same thing with an app but more fluidly.

What were your short films about initially?

First, I grabbed the WhatsApp audio that my little cousins sent me. I have little cousins, one of six and the other eight years old. They were the characters; I drew them and made them animated. And then, one day, I don’t quite remember how it occurred to me to play with audios of musicians, probably because music is something I constantly have at hand.

Besides, I saw Midnight Gospel that year, an animated series made with audio from a podcast. I loved the idea. I don’t know if everything they discussed interested me, but the idea was great. When you make an animation, you usually write a script and then call someone to do the voice. Here they took something that already existed and animated it. That’s what interests me. I understood that you could reinvent anything just by reinterpreting the context.

“I wanted to make animations that lacked cynicism because there was already a lot of cynical material on the networks. I wanted to avoid cynicism and solemnity. I wanted to take care of those two extremes. And if I’m going to laugh for a while, don’t make fun of the artist. Let it be playing with what the artist says.”

You use audio from famous musicians, but your videos are not necessarily about music. Some of them have more introspective or philosophical reflections. It’s as if the music were an excuse to talk about other things.

I found that aesthetic along the way. I expected to make four or five animations, nothing more. It was just for fun and to send them to my friends. But I started to like it. Then I started improving my tools: I started with a cell phone, borrowed a tablet, and now I have a pretty big tablet with which I draw. I also started to read more about animation, study, and see animators’ work with different eyes.

And concerning the audio, it was also something that I found. I wanted to make animations that lacked cynicism because it seemed to me that there was already a lot of cynical material on the networks. I avoid cynicism and solemnity. I wanted to take care of those two extremes. And if I’m going to laugh for a while, don’t make fun of the artist. Let it be playing with what the artist says.

We have to talk about Spinetta, one of your recurring characters.

At one point, I realized that Spinetta is like a master Yoda. Everything he says seems loaded with tremendous importance because he speaks beautifully. If you go too much with that, it loses its grace. But if you change the context, it becomes much funnier.

There are more or less radical ways to change the context. Some of your animations are dialogues that never really existed.

There is one that I like in which Fito, Charly, Spinetta, Cerati, Calamaro, and Fabi appear. They are all talking at the Friends bar. Obviously, that never happened. And, of course, it’s a lot of work to put together a conversation like that because you have to watch three-hour interviews to see if, at some point, they say the word “coffee” or something like that, but it’s pretty funny.

There is another animation in which everyone is playing soccer. For example, Cerati says: “they kicked me out,” and clearly, in the original audio, he is not talking about being kicked out playing soccer. Or Spinetta says: “This is my most official center,” and he’s not talking about a long pass either. Those things are pretty fun to imagine.

Do you have favorite episodes?

I really like “El Mundo de Salva.” It’s something I did last year. I wanted to try something different and see if I could tell something more serialized. For now, “El Mundo de Salva” has five episodes, but there will be five more this year. The idea is to show the inner world of Salva, the character with the fox mask. We see how he enters this strange world of dialoguing with artists. We don’t know if he imagines it, if he dreams it, or if he really travels.

I like the last chapter, with David Bowie and Keith Richards. Also, the previous one is special because we see Salva in his childhood. It’s like an episode of a Hanna-Barbera show but with the Beatles. Then, of the short films, I like one with Jeff Tweedy, the lead singer of Wilco. What Tweedy says is beautiful.

I usually put a lot of love into Fito’s songs because I love Fito very much.

Fito Páez came to record a script you sent him, right? How did that happen?

It’s an episode called “Ruta Salvaje,” the final episode of season 2. It’s the most extended episode; it lasts 12 minutes. I wanted to tell a story from a script and asked Fito to record the voice. We had already chatted a couple of times. He had told me very nice things about the animations, so I wrote him a very long message, telling Fito, look, if you don’t want to, it’s all right, and he said yes, send it to me. I’ll do it in one go, and he recorded it.

I sent him the animation, and a few days later, he answered me and told me he wanted to open the show he would do in Rosario with that video.

Have you collaborated with other musicians in these animations?

Calamaro also liked them a lot, and he asked me to make a video clip for him one day. It came out in October last year as the re-release of the album Honestidad Brutal. The song is called “Pero Igual.” And then I’ve had talks with some other musicians. I know most of them have seen the videos.

Does Salva’s mask have a special significance?

Yes, not precisely that mask or that it’s a fox mask, but the idea of the mask. I had been releasing albums with a group called Martin Ameconi y Los Pulpos, and I wanted to change that and play a little with the theme of identity. So I stopped using my name, called the band El baile de los Salvajes, and decided to appear on the cover of the album without my face showing. Then I went to look for animal masks in a cotillion here in Buenos Aires, and the only thing I got was a very poorly made fox mask, but a friend of mine intervened, painted it, cut it out, and it turned out nice.

There is an episode that talks about that too. It’s the one where Salva is with Bob Dylan. I extracted audio of things Dylan said about identity. One of them is that life is not about finding yourself; it’s one of those phrases from a self-help manual, like: “travel to find yourself.” I always thought they were bullshit, and so did Dylan. So he said that life is not about finding yourself because there is no “yourself.” It’s about creating yourself and creating things. And I found that charming. Then he says something about masks, and he talks about the Rolling Thunder Revue, a tour Dylan did in the ’70s, where all the musicians were in costume. It was a mix of a musical show with a circus; they all wore masks. In an interview, Dylan says that that tour lacked more masks because when someone wears a mask, they’re going to tell you the truth. Actually, that’s Dylan’s ripping off Oscar Wilde, but that is where the idea came from.

Putting that character with the fox mask, which is like an alter ego, is also a kind of signature that lets people know that all these videos come from the same guy.

Have you gone back to making music since it is finished the confinement?

The last thing I did was called Ninja Salvajes, which is a union of two groups, Los Ninjas Púrpura with Baile de los Salvajes. They are very nice songs that I did with a musician friend, Juan Filipelli, a great musician. We did our own La La La La, which is an album that Spinetta and Fito did in the 80s. So you can listen to that too.