The end of video games (as you used to know them)

More than video games, the Hermanos Magia create digital narratives that speak to issues that touch the human condition: death, depression, loneliness, and confinement. Their latest project uses virtual reality to build a memorial for activists killed in the Amazon. In a world that is still suspicious of its usefulness, this team of artists considers video games as complex an art as cinema.

By Alonso Almenara

When we arrived at Gabriel Alayza’s house, his colleague Jaime Chirif didn’t notice a visitor. He was wearing Oculus Quest 2 glasses, an immaculately white, minimalist design that made him look like a Martian. At some point, we looked at Chirif and caught him bent over, almost on his knees, staring at something on the floor: a gem, a potion; how should we know? He picked up the virtual object, manipulated it from one side of the room to the other, and smiled, stupefied as if the magic of immersion was in that minor detail.

Chirif works with Gabriel and Mateo Alayza, the Hermanos Magia studio’s founders, specializing in graphics, illustration, and video game creation. An incipient industry in Lima has not prevented them from being recognized globally. They have won various awards, including first place in the Cultural Heritage Game Jam 2021 for the game Purunmachu, and their creations are available on all major consoles. But the contours of their games are strange, experimental. Their intention is not to compete with best-sellers like Call of Duty or Elden Ring: they create games with a sensibility of their own, adult and introspective, placing themselves at the forefront of what is happening in the indie scene of digital narratives.

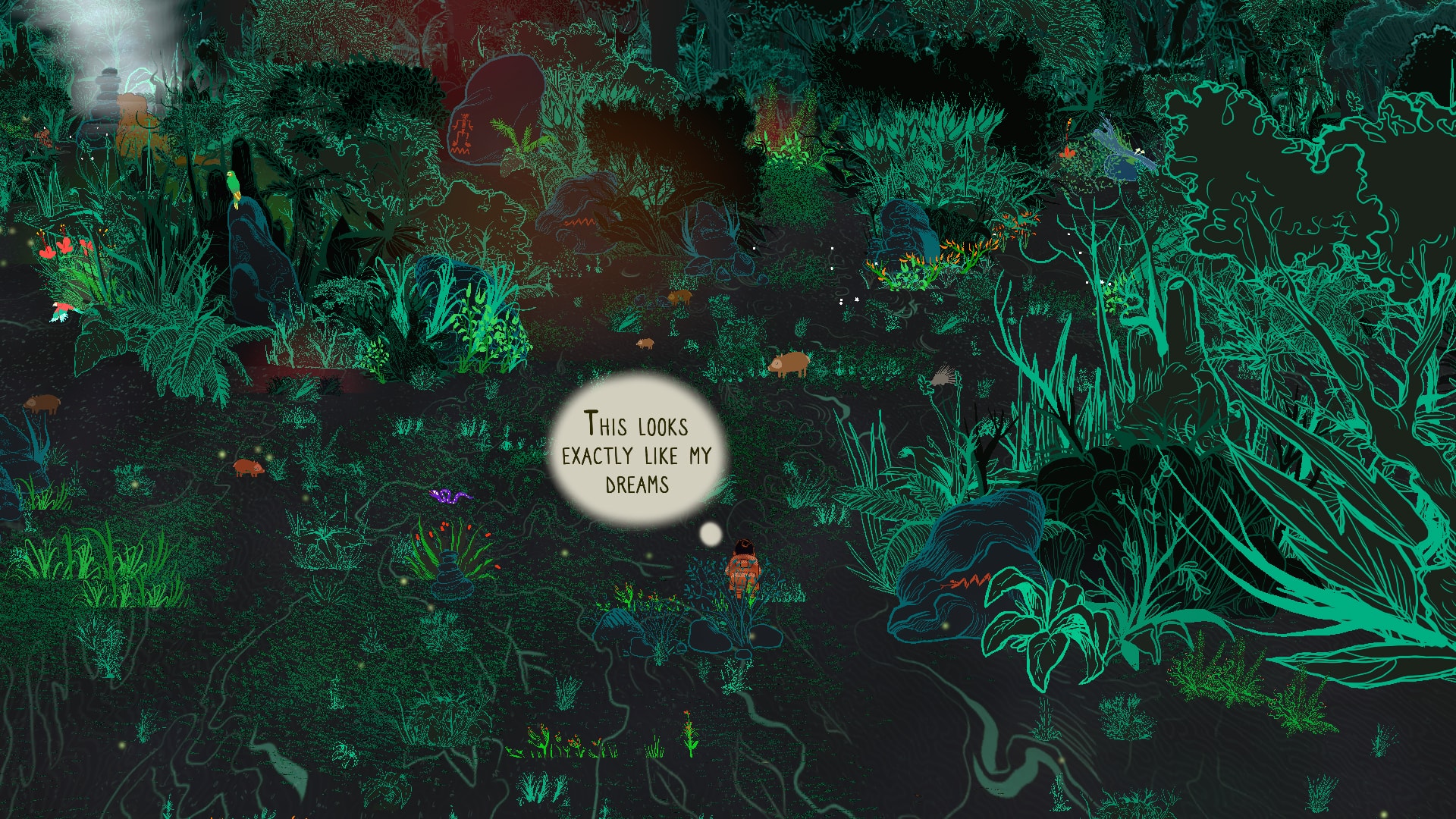

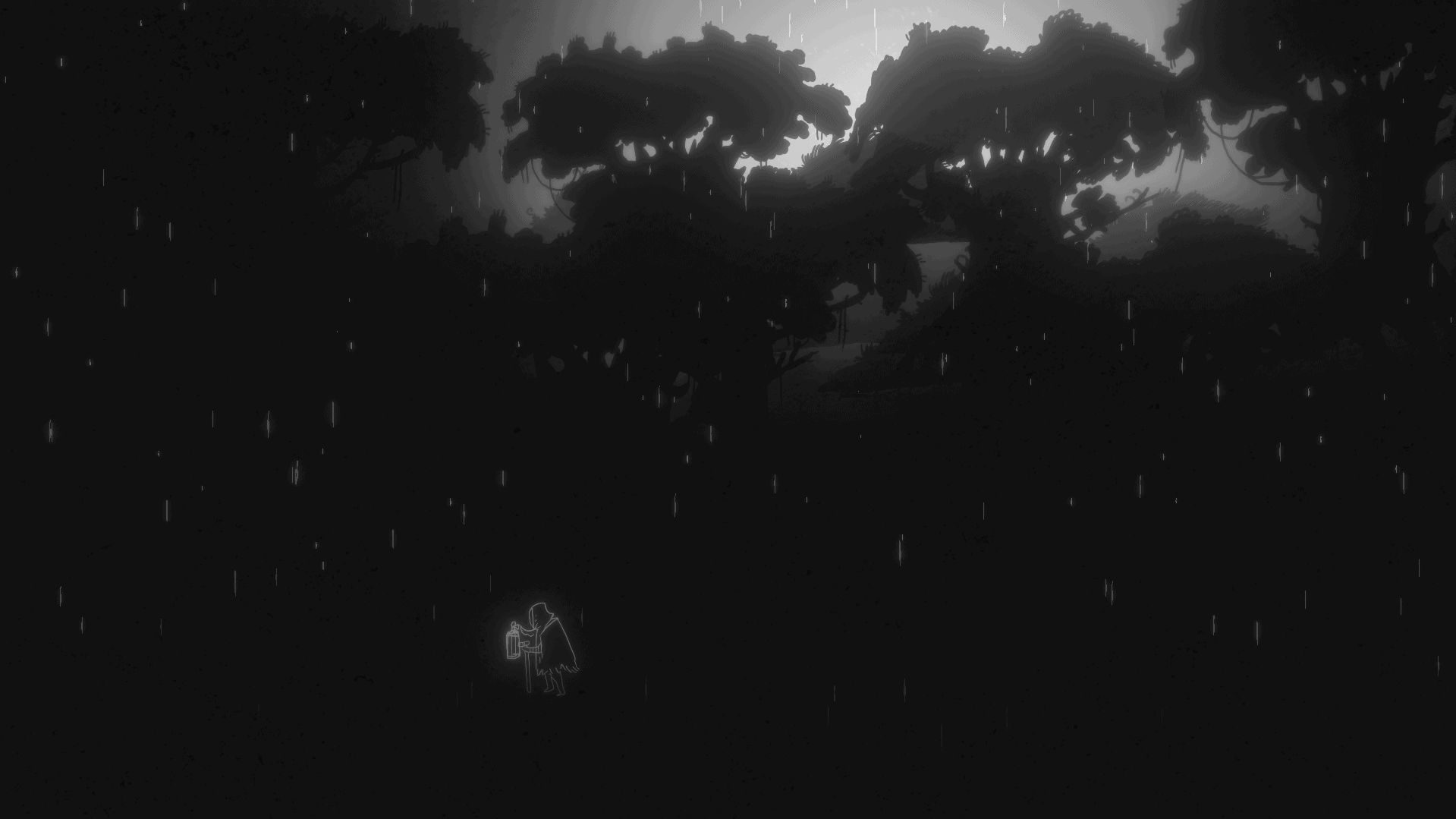

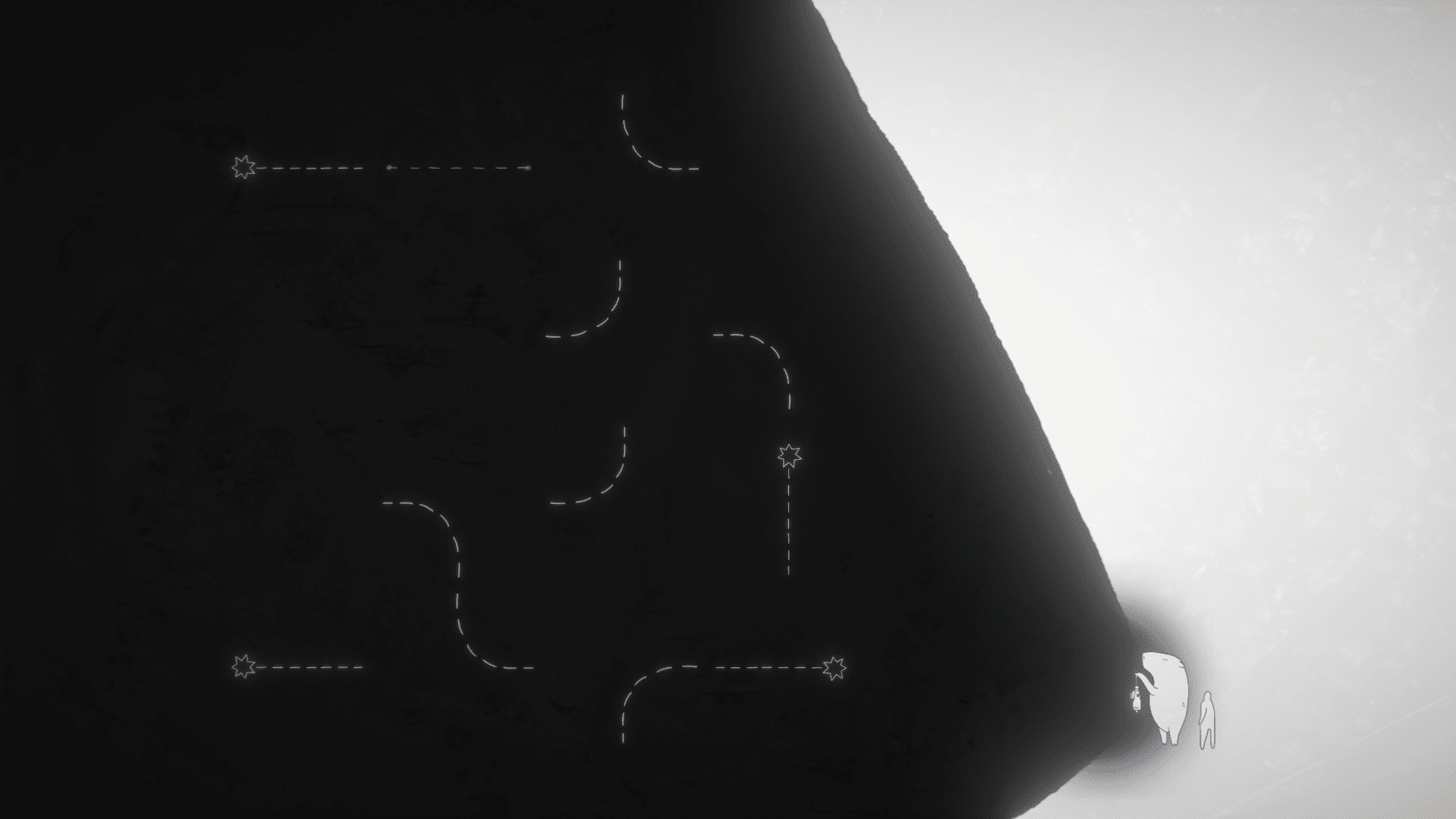

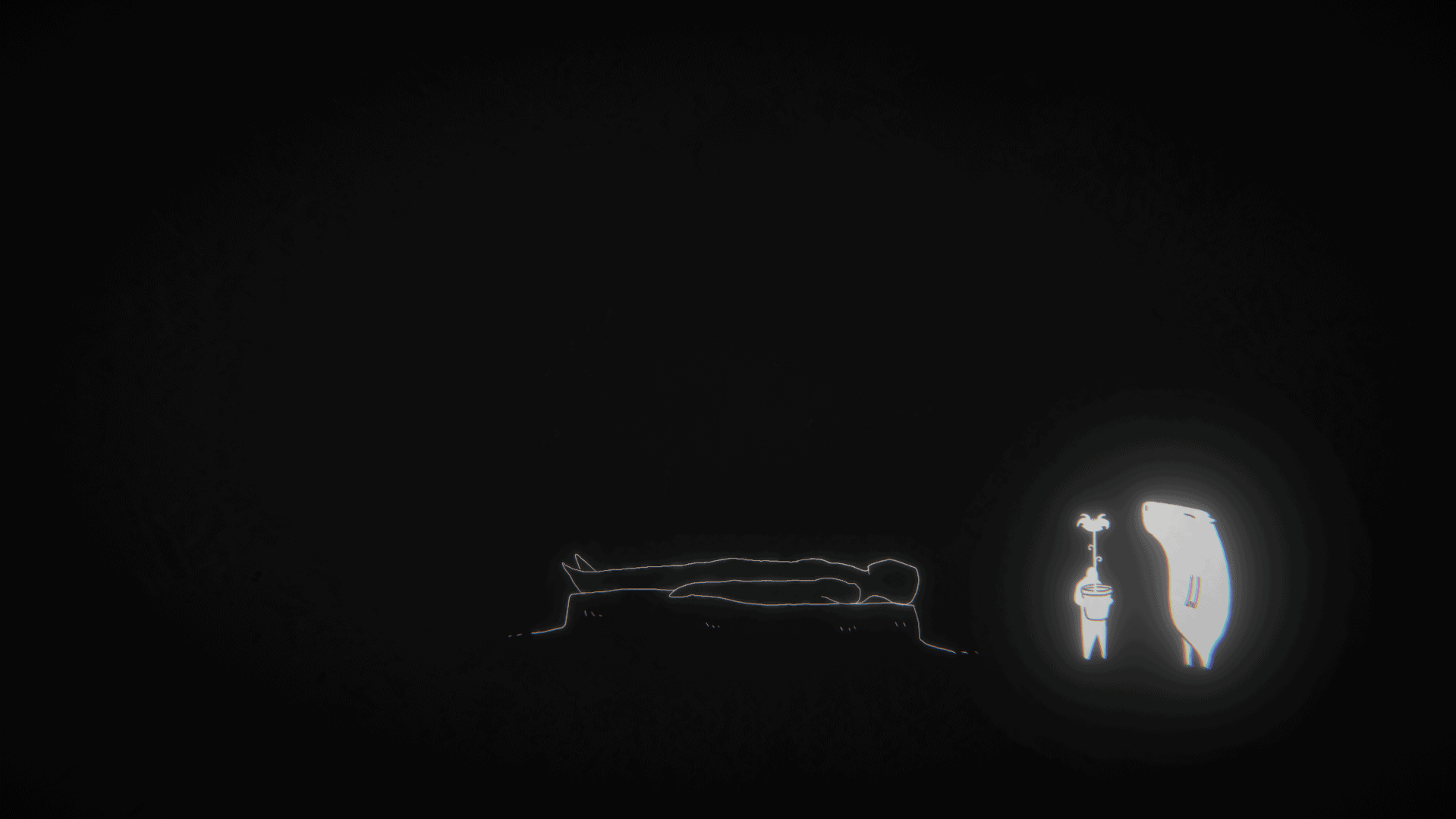

Arrog, for example, has a monochrome aesthetic and explores the theme of death from the Andean peoples’ vision; a Screen Rant reviewer described it as an experience between a puzzle game and a digital art installation. Another game, Inner Room, deals with confinement, depression, and the labor crisis during the pandemic. Both games feature music by Jaime Chirif, a jazz composer with a trained ear for creating atmospheres and sound collages. Together, these friends make proposals that they consider transmedia experiences more than games.

But their ambitions go beyond the video game medium: Gabriel bought the VR headset to work on a new project, a digital memorial for environmental activists killed in the central Peruvian jungle. “It’s a complex subject to work on,” he acknowledges, “but I think introducing virtual reality elements into memory processes can be valuable because of the visual, almost tactile closeness this tool gives you.”

Anyone who talks to them is intrigued by their proposals and by the singularity they have in the panorama of digital creation in Latin America: after all, the experience of Hermanos Magia shows that it is possible, from the south, to create alternative author content and succeed in a market saturated by hyperproduction, investment in increasingly powerful graphic engines and the thoughtless use of violence.

Guts of a pandemic life

Gabriel describes Hermanos Magia as “an exercise of leaving aside what we had in front of us to explore interests that have to do with childhood, but also with the Internet and very adult things.” He trained in visual arts but quickly discovered that he was more interested in comics, children’s literature, and anime. When he founded the studio in 2010, Peru’s graphics and illustration scene did not have the development it has now. “The illustrator was always subordinated to organizations that had nothing to do with his discipline,” recalls Mateo. The studio gave them the possibility to experiment. “It wasn’t the space of the artist’s singularity, but it linked us to all those other media that people weren’t taking with arts training.” They have worked with publishing labels, universities and NGOs dedicated to safeguarding the environment. They came to video games as they did to graphics a decade ago: as part of a developing local industry, but knowing there is plenty of room for growth.

“Video games are in a time of transition where all the market spaces are not yet under control,” says Mateo. “That leads to huge numbers of indie games being produced worldwide. Many of those productions fail, but many others find an audience.” He compares the evolution of the video game industry to that of cinema: “They have in common a very indie origin, but the search for economic returns quickly turned them into mass entertainment media. When production tools become cheaper, spaces for more independent discourses open up again. As in cinema, there comes the point in which there is a mainstream mass entertainment of great quality, but also, in an underlying way, other things start to happen, hybrid things”.

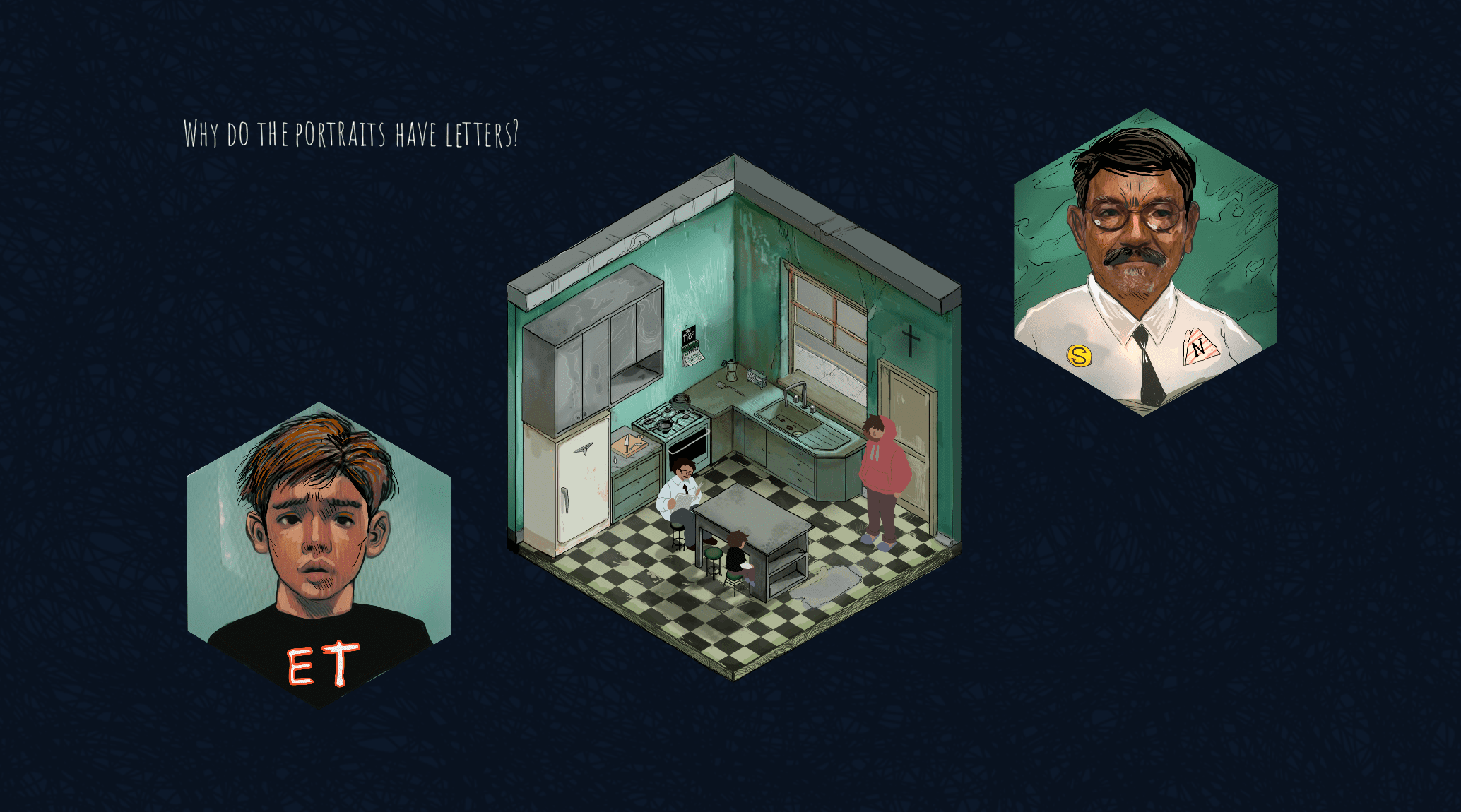

Inner Room has that kind of alternative aesthetic. A protagonist is a young man from Lima who is locked in his room in October 2020, during the most uncertain period of the covid-19 pandemic. He eats fast food, wears a sweatshirt and slippers, and is burdened by work problems. His room does look like a prison: it’s small and gray, and there are tally marks on the walls. But the realistic setting is upended when the character learns over the phone that his father has died. Suddenly, the room is invaded by dreamlike images and childhood memories. The space becomes the projection of a tormented inner world.

Inner Room is just a teaser: a twenty-minute experience that barely gives a taste of what the game will be in its final version. But in that short time, the player puts himself in the shoes of a character who is going through a depressive episode and understands that he needs therapy. The healing process begins with a question: where does his inability to cry come from?

Mateo Alayza: “In Inner Room, the experience had to make the player feel the frustration of what it means to be locked up, and therefore it had to be uncomfortable, hard, quote unquote boring. The challenge was making boredom mean and therefore attract, to generate a bond with the player.”

Mateo explains that games use a mechanical structure to break down experiences. In programming jargon, “mechanics are systems of rules. The combinatorial possibility they offer you determines how the player moves emotionally through the game. And sometimes, it happens that the mechanics lead you to a question or an interpretation of something. The mechanics can function as a metaphor.” This idea is developed in Arrog so that, although simple, the mechanics have an expressive component.

The game is linked to death, a non-occidental idea of death. “Many legacies condition our look on that subject. It is a question that has no solution but to which we constantly return, trying to close it of meaning,” says Mateo. “The important thing for us was to create an experience that leaves you with a kind of openness,” Jaime notes that in the mainstream video game, the relationship with death is almost always utilitarian. “You kill to get something, like in Call of Duty. But from a personal perspective, death is something else. It has to do with a change in the experience of time. And Arrog explores that it’s something you feel.”

Jaime shares with Alayzas an affinity for the album book: a genre that is distinguished from the illustrated storybook by the particular dynamic that is established between text and image. “Album books are artifacts that, like video games, are viewed pejoratively: they are thought to be exclusively for children or minor literature,” he says. “What interests me is the narrative device. The relationship between text and image is constantly tense, which leaves gaps.” Before working with the Alayzas, Jaime experimented with musicalizing album books made by Micaela Chirif, his mother, a renowned author of this genre. Mateo adds that Arrog is a development linked to that sensibility: “he translates that experience into a digital language.”

Gabriel Alayza: “When one searches for information on murdered environmental leaders, the results that Google returns are always police reports. These people are defined by their role as victims. There is no information about their struggles. We don’t know how they lived or their role in their communities.”

“Making video games is a problem,” Mateo acknowledges. “It takes a long time, the learning curves are slow, it’s expensive, and it’s very demanding. China now accounts for 60% of the world market: it’s the segment that independent developers could depend on for stability, but Chinese market regulations are ultra unstable because of how their government works.” With Arrog, the Hermanos Magia managed to jump the competition fence thanks to the games’ awards and the support of international publishers. “But it’s brutal how many games are being uploaded to Steam. It’s fierce and bleak territory. People who are in the indie market are scrambling for funding.”

The danger, for the Alayzas, is creating content that aspires to copy mainstream industry know-how simply. Mateo says that Google selected his studio to participate in a forum for Latin American developers. “They were training us to monetize games, essentially introducing sophisticated collection methods that come from the casino. That’s what happens in Latin America: there are valuable indie efforts, but they are subservient to those notions that come from a market that we are always looking at from afar. We don’t assume a place of ownership over our proposals, our heritage, our voices.”

Virtual memories of violence

Hermanos Magia’s most recent proposal is called Luto Verde: a collaboration with artist Eliana Otta to create a digital memorial for environmental activists killed in the central Peruvian jungle. “When you search for information about these people, the results Google returns are always police notes,” says Gabriel. “These leaders killed in unclear circumstances are defined by their role as victims. There is no information about their struggles. We don’t know how they lived or their role in their communities.”

Funded by the German state, Luto Verde began as a project combining a website and an exhibition with being screened in an exhibition hall in Berlin. The development team then came to the idea that it would be much more interesting to have a downloadable app that would allow users to have a virtual experience that would put them in touch with the daily lives of these leaders. In that process, Eliana Otta traveled to the communities, collected testimonies, and ambient audio, and recorded video with a 360-degree camera. For the pilot project, a particular leader was chosen, and the objects by which his relatives remember him have been physically scanned: his tools, his cushma (or traditional costume), his community leader’s staff, the radio, and the slate with which he communicated with his community. “This has allowed us to generate 3D environments and objects you can interact with using VR glasses,” explains Gabriel. “In addition, clicking on them will open specific videos and audios about these people’s lives, where those same objects are going to be present.”

The Hermanos Magia don’t know what the response to Luto Verde will be in a country where VR glasses are still too expensive, historical memory is a field of continuous confrontations, and the struggles of indigenous peoples to preserve nature tend to be erased from public discussion. But Mateo is mildly optimistic. He notes that Luto Verde is an experiment, but it is consistent with the work they have been doing in the studio. “Our games don’t work to distract you. They focus you on a theme and delve into that.”