Those Stones you Threw at Me as a Child do not Hurt me Anymore

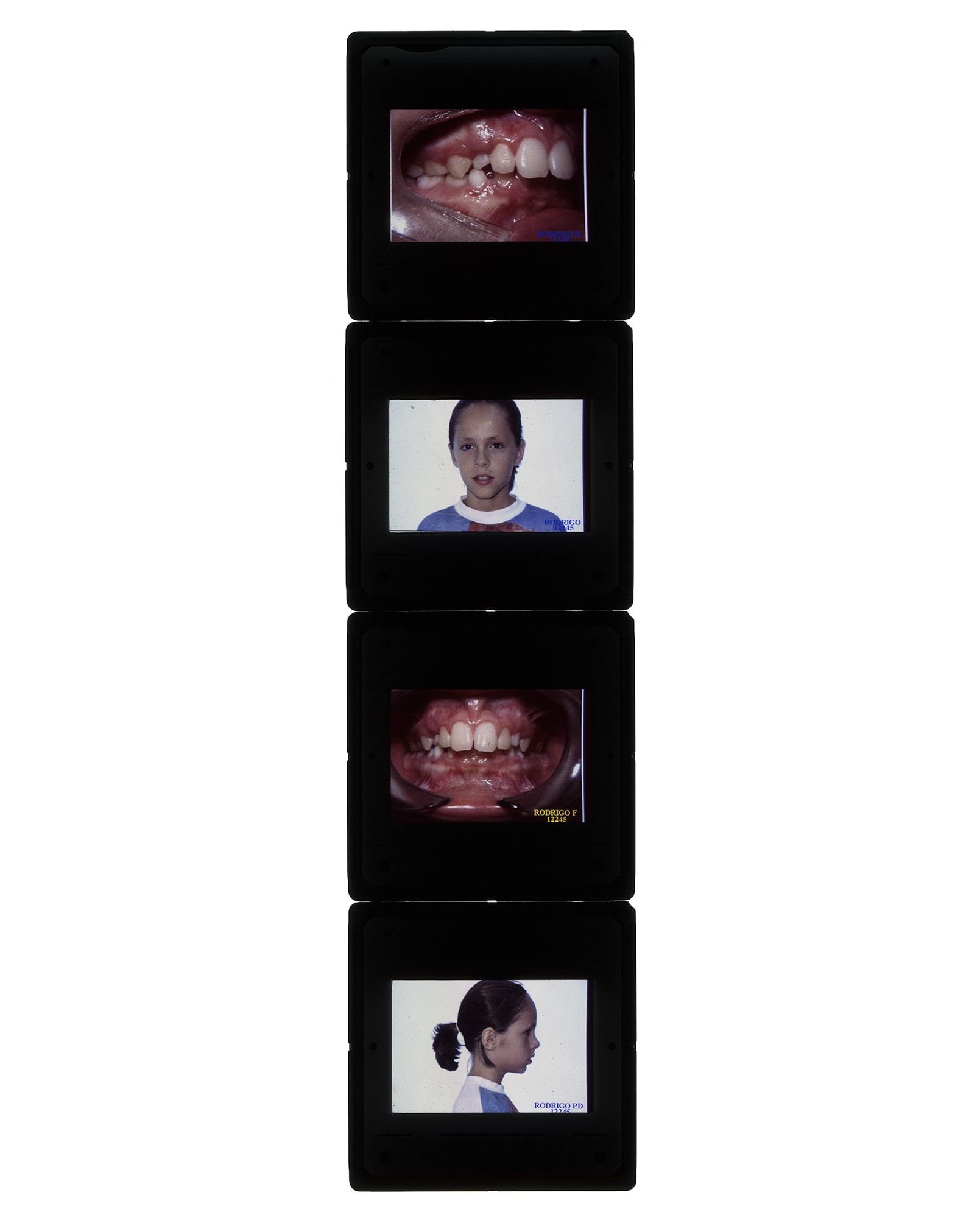

the name of the project of Rodrigo Masina Pinheiro and Gal Cipreste Marinelli, a couple of photographers from Brazil. It is a photographic series that intertwines their biographies to tell the violence and fear suffered by sexual and gender dissent, childhood, tenderness, and courage.

By Marcela Vallejo

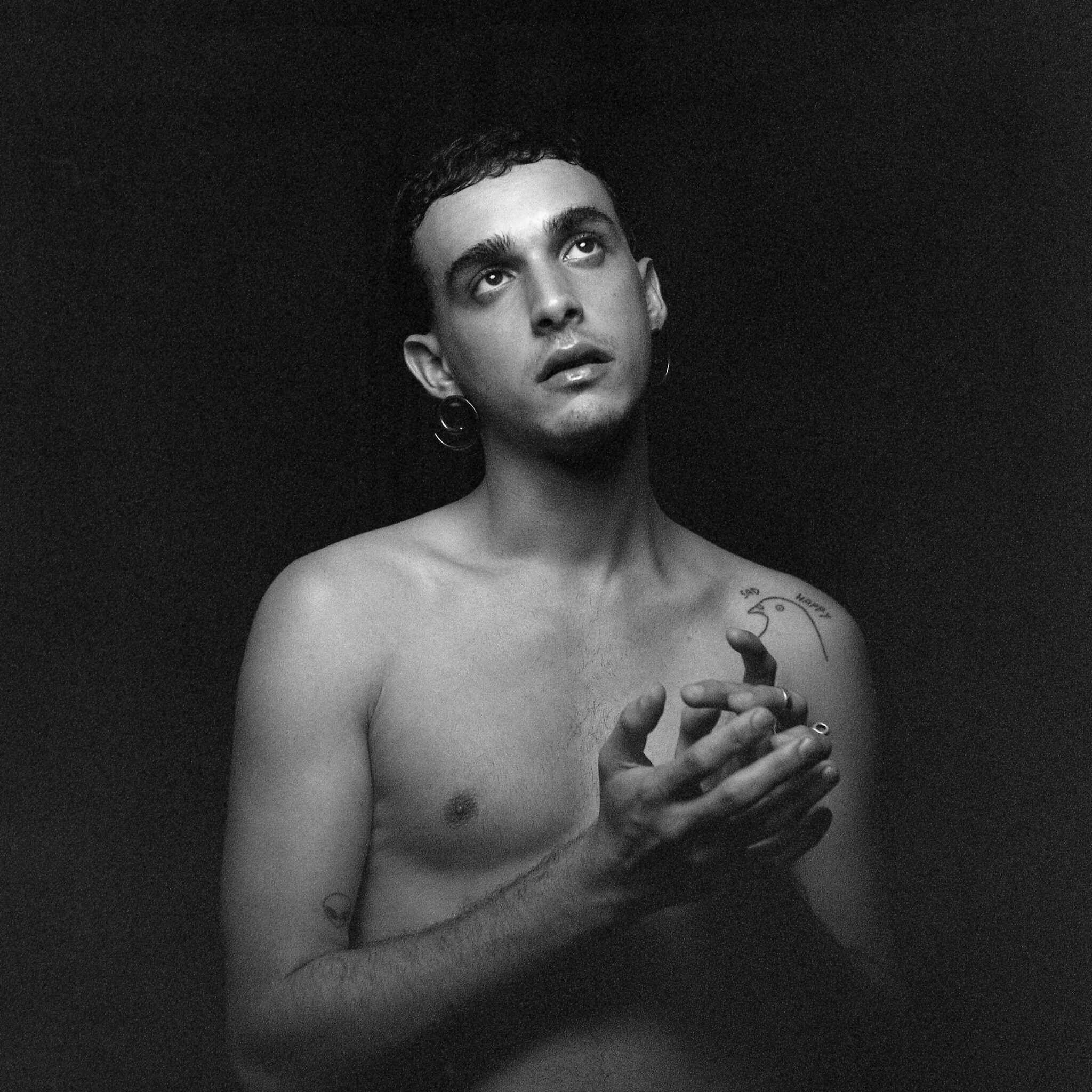

Hiroshima was a confusing child. At first glance, Hiroshima looked like a girl. The confusion followed daily on the way home from school. It was on the street and only on the street that Hiroshima needed to think about what they was. Their mother accepted her without ever thinking about it.” One day, on their way home from school, Hiroshima was attacked: at age ten, they was stoned in the street where she lived in Rio de Janeiro. Meanwhile, “Gal wore so-called feminine clothes on her adolescent body. She did not yet see herself as a non-binary trans woman.”

G and H is the name of the project of Rodrigo Masina Pinheiro and Gal Cipreste Marinelli, a couple of photographers from Brazil. It is a series of photographs in which they interweave their biographies. They thought about this weaving thanks to a coincidence that they describe as “expressive,” perhaps because of its impact. The H in the title stands for Hiroshima, Masina’s childhood nickname. Their paternal grandfather called them that because they was born on the anniversary date of the atomic bomb. Gal was born the same day as the U.S. president who dropped the bomb.

For Masina and Gal, it isn’t easy to talk about this project. There are many things they have not yet been able to say, things that are difficult to express in words. However, this series “is, in a certain way, all transformed. Outside the body. Outside of us,” says Masina. And they states, “that’s why this series talks about gender, but not with many pictures of the body because it is an experience already purged.”

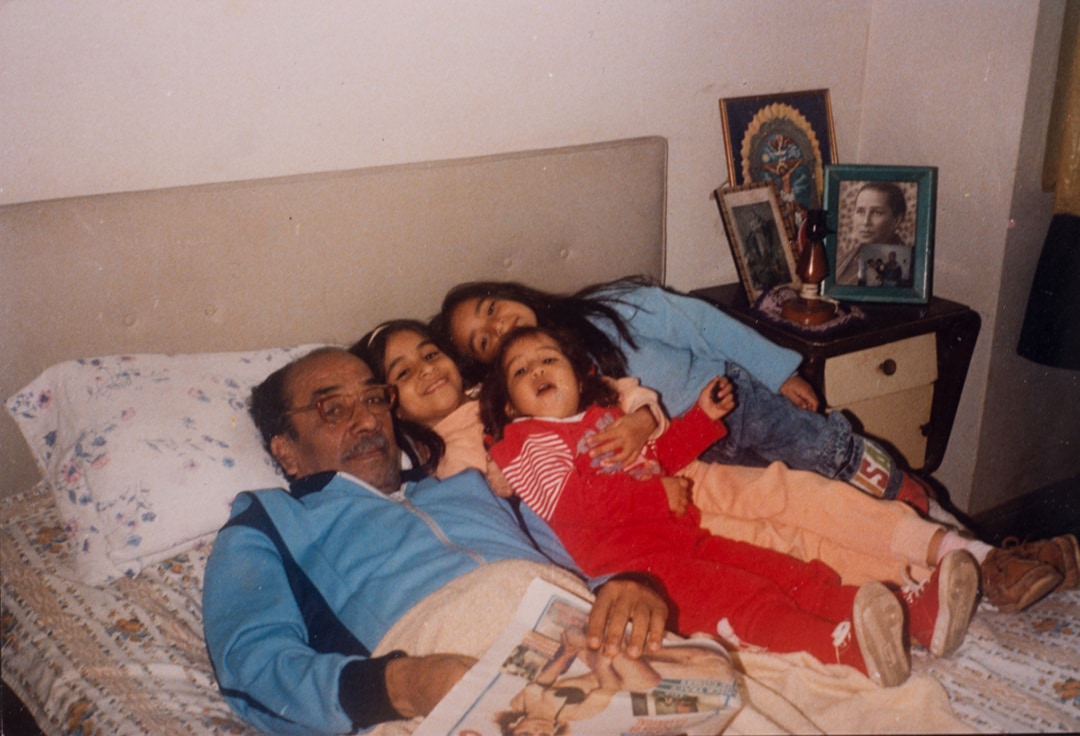

When they were working on the images, Gal had recently changed their name as part of their gender affirmation process. The situation with Gal’s family was complicated. Hence also the intertwining of the stories. “Gal’s familial love is represented in the series,” they say in the text introducing the book they are building. “However, a religious idea stands between maternal love and unconditional understanding.”

“I remember feeling that my life was ridiculous,” says Macina, “because I was always afraid. Fear of telling the things that happened to me, of being who I am, fear that people would laugh at me because mine are experiences that are out of the norm.” That’s why it was vital for them to collaborate on this project because they could listen to each other and meet each other. The value of such a collaboration is, for Masina, “a legacy of courage.”

Of course, these are not just Gal’s or Hiroshima’s experiences. They know it. The interweaving of their biographies has allowed others to come forward to tell their stories. They have managed to break through that legacy of silence a bit.