To die as drug mule

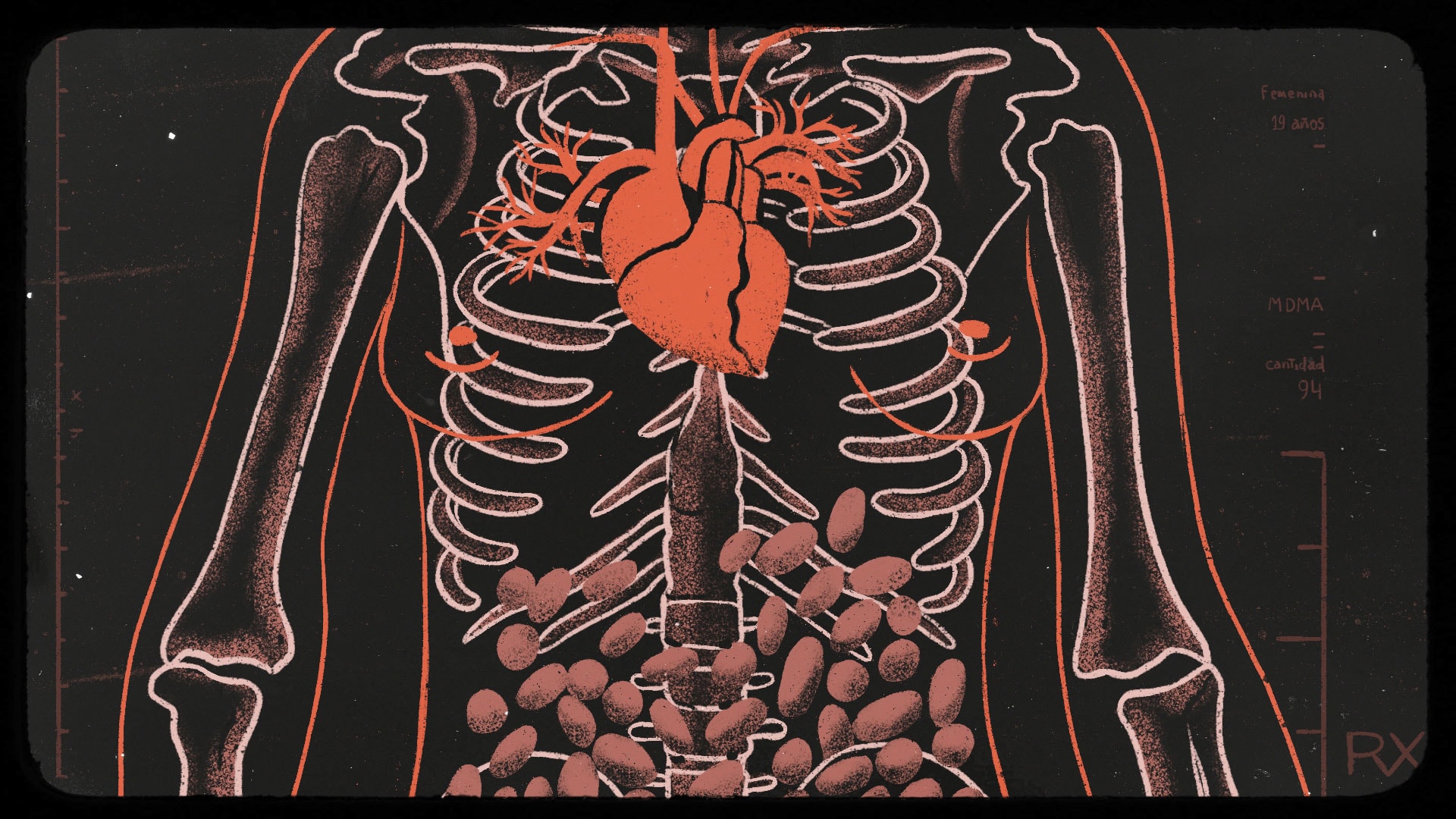

Death irreversibly settled in the young body of Miriam Natalie Alencar Da Silva when two of the 66 plastic capsules that she carried in her stomach were opened and she had not been able to expel them. The MDMA began to spread like poison in the water. A single ecstasy capsule cleft is a thousand-fold potentiated overdose. Every time an envelope bursts in the intestine, a gate opens through which the substance drains and passes directly into the bloodstream. The heart stampedes and there is no turning back. Without medical assistance, capsules that can’t get past the gut and on their way become time bombs.

Miriam was 19 years old and had arrived in Argentina from her native Brazil, with a total of 94 pills of extremely high purity MDMA in her belly: half a kilo of pills the size of the thumb of one hand each, wrapped in a blak ribbon. On June 28, 2017, at the Ministro Pistarini Airport in Ezeiza, the scanner did not detect what was in her colon and liver. She did not end up in jail, but she had a fatal fate.

When a “human courier” does not achieve its objective, it becomes disposable. The man who had contacted Miriam for this task threw the dying body from a moving car in the Buenos Aires neighborhood of Villa Devoto. She was barefoot, wearing jean shorts and a short T-shirt. The scene of the dispossession was recorded on security cameras. When the neighbors found her and asked for help, it was too late: Miriam had ecstasy in her blood and in her guts.

“Mulas, tragonas, ingestadas, envases, vagineras, correos humanos, aguacateras o capsuleras” (Mules, easter eggs, Kinder Surprise, swallowers, body packers): these are the multiple ways of calling those that put the body as a survival strategy. Behind the stories of women who submit to being transformed into containers out of necessity, coercion or deception there are plots of social exclusion, poverty and, in some cases, sexist violence that they suffer in their homes or surroundings.

In the universe of drug trafficking, all the structural inequalities of patriarchal society are replicated and even strengthened: they manage the invisible threads of the great drug trafficking networks while they lay down their bodies and they are imprisoned or killed. The sexual division of drug trafficking thus becomes a framework of impunity for men and one more form of precariousness of feminized lives. The distribution by gender roles is a distribution of risks.

In the last two decades, the population of female prisoners in Latin America and the Caribbean increased at an accelerated rate, much faster than that of men. The main cause is drug-related crimes. The 2018 World Drug Report of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNDOC) indicates that, in some countries of the region, these crimes rank first or second among the causes for the incarceration of women , but they only rank between second and fourth place for men.

The incarceration of women for crimes related to trafficking of substances considered illegal is a worldwide problem. According to the same UNDOC report, 35% of the incarcerated population of women worldwide is in prison for drug-related crimes, while 19% of men incarcerated in the world are in prison for this reason.

Although there are figures on imprisonment, little is known about the cases of deaths of women who use their bodies to transport drugs. Miriam’s case was the exception. Two years after the discovery of her body, the Oral Economic Criminal Court 2 sentenced Hendrik Binkienaboys Dasman to life imprisonment for a list of crimes that revolved around the abandonment of the young Brazilian: smuggling, possession of drugs for marketing purposes and aggravated homicide. The judges also punished Dasman’s partner, Danilcia Contreras de León, as responsible for aggravated homicide and possession of narcotics for marketing purposes.

A failure in the traffic chain and a body thrown in the heart of Buenos Aires was the thread to be able to ascend in the chain of responsibilities on which judicial investigations rarely advance. How many other dead or missing mules will there be in the region where more and more women are imprisoned for drug-related crimes?

A failure in the traffic chain and a body thrown in the heart of Buenos Aires was the thread to be able to ascend in the chain of responsibilities on which judicial investigations rarely advance. How many other dead or missing mules will there be in the region where more and more women are imprisoned for drug-related crimes?

Just as in the universe of legal jobs, women have the worst jobs, the most precarious in illegal jobs too. Except that the famous “glass ceiling” in the