What You Left Me After the Shipwreck

Regresamos con Novedad is not only a photobook about Colombian Pacific cabotage ships, those small vessels that transport merchandise and passengers. It is, in fact, Lilia Cuero’s homage to her father, a machinist who died in the middle of a shipwreck. Through photos, her father’s logbook, and interviews with other Afro-descendant crew members, Cuero recovers a part of his memory.

By Marcela Vallejo

The last time Lilia Cuero spoke to Melanio, her dad, was Wednesday, July 3, 2019. She was in Medellín. He was working in the port of Buenaventura, as usual. She doesn’t remember what they talked about exactly, only that Melanio called her to see how she was doing. Her father was a hardened man of the sea, hardworking and loving, who spent his free time with his family, especially playing with his granddaughters. They had already talked about taking some pictures. Before hanging up, Lilia reminded him that they would do them when they met again.

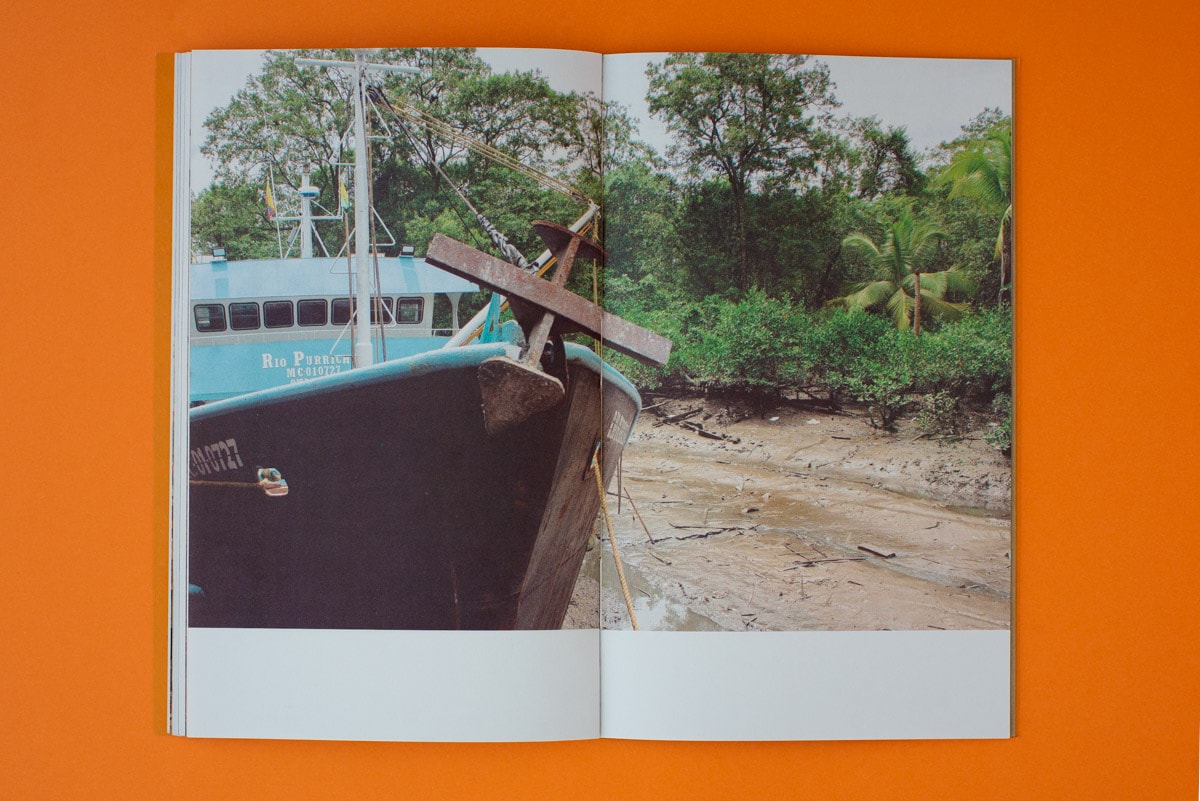

The day after that last call, Melanio embarked as engineer of the ‘Karol Tatiana,‘ bound for Chocó. It was a dark night in the Pacific, the rain did not stop, and there was a lot of fog. The ship was carrying an excessive load and was not in the best condition. All this meant that two hours after setting sail, the ship was wrecked at Buoy 2 in front of Bahía Málaga. It carried 16 passengers and five crew members: one passenger, the cook, a sailor, and the engineer died. The Coast Guard was unable to act quickly due to bad weather. Melanio Cuero, with the strength of his 52 years, swam and swam in search of dry land. The next day, his body was found near La Bocana beach.

After a month of mourning for her father, and perhaps as a tribute, Lilia Cuero exhibited her series on coastal shipping for the first time. The event was the closing of Sacúdete, an educational program in which young people from Buenaventura, like Lilia, learned photography, video, and graphic design. Lilia says that, in those classes, her teacher Andrés Millán told her that before shooting the camera, she should write and draw her photos, thinking very carefully about what she wanted to create. She knew she was interested in boats and people like her father.

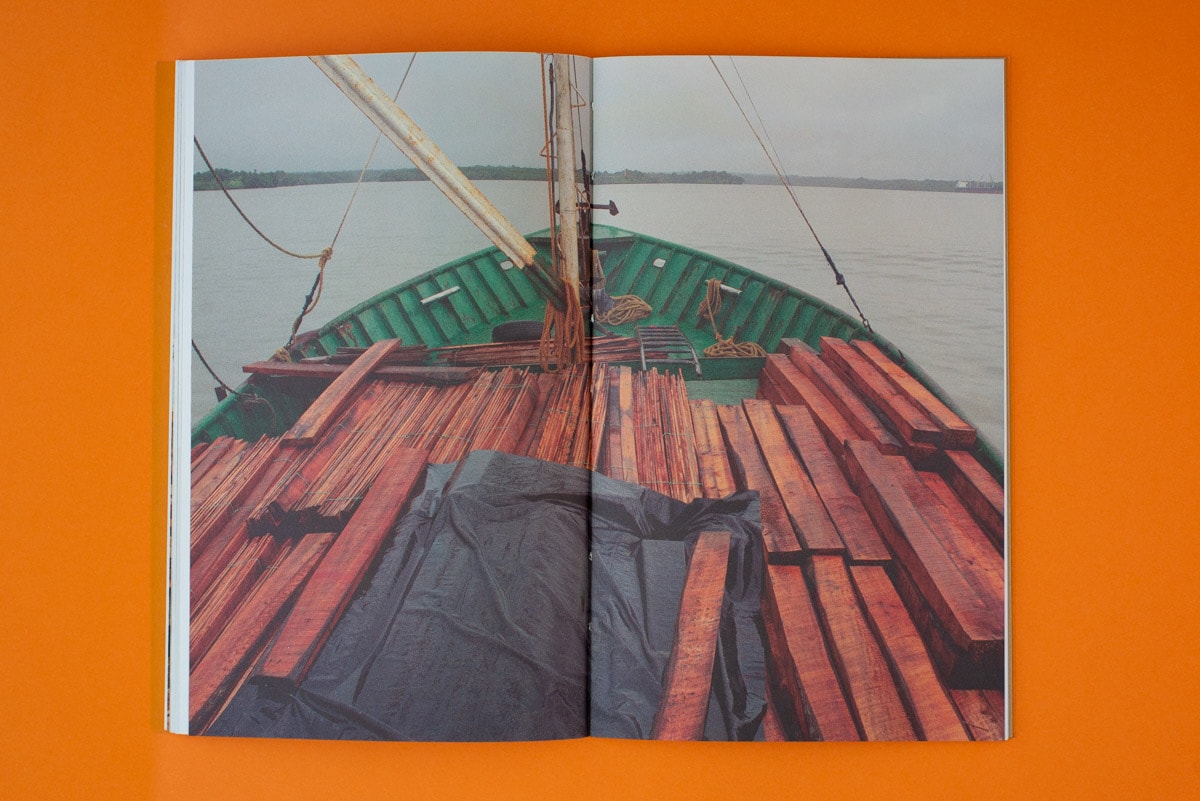

Cabotage ships are small boats that transport goods such as food, water, gas, necessities, and passengers to Colombia Pacific coastal and coastal populations. They leave, in this case, from Buenaventura, the collection center, to places like Yurumanguí, El Naya, Guapi, López de Micay Timbiquí, Tumaco, Barbacoas, Nuquí, and other places where neither cars or airplanes can reach due to the rugged geography.

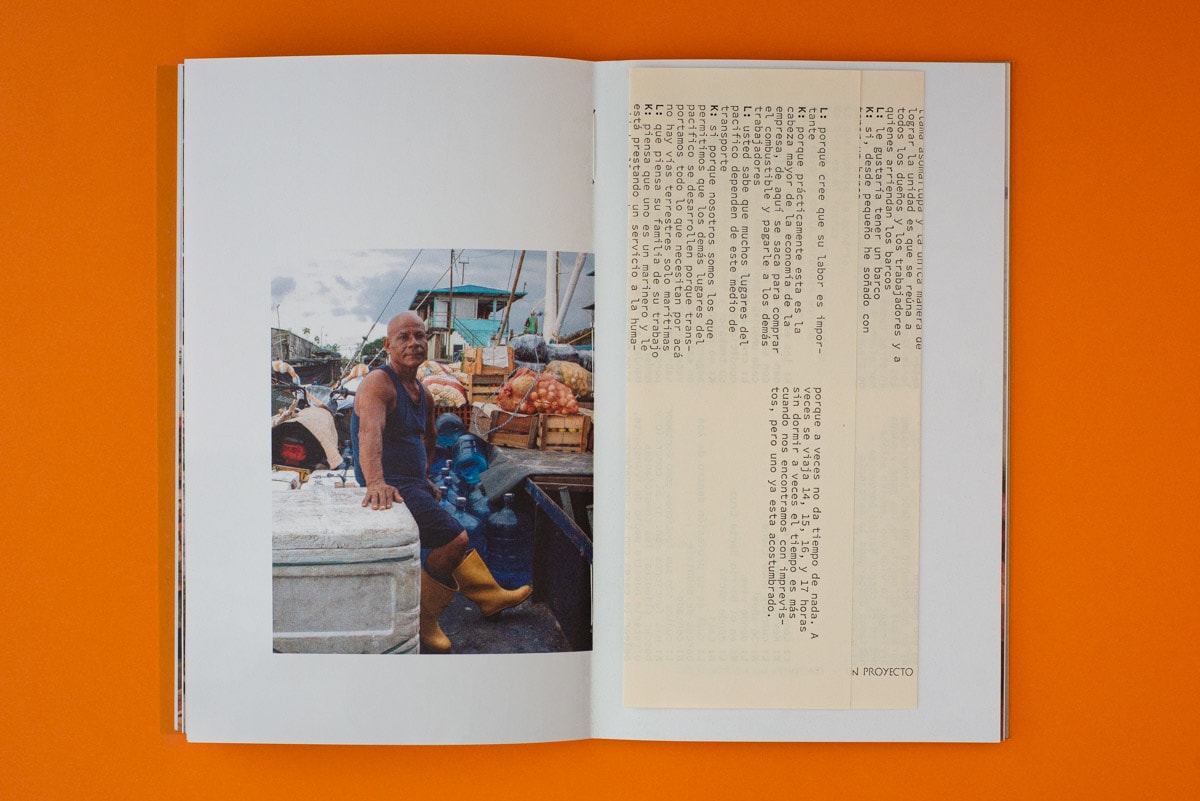

“I wanted to take pictures of my dad because I was learning to take pictures and because I saw that there were beautiful places and boats,” says the 32-year-old photographer. “It was an environment that was familiar to me and that filled it with beauty.” Over time, portraying the world of coastal ships and their crews became, for Lilia, a reunion with her father.

In 2020, Lilia won the Expedición Sensorial scholarship from the Ministry of Culture. Her tutor was visual artist Georgina Montoya, who taught her the path of the photobook as an expressive tool. Despite her determination and determination, when in 2022 she won the Crear Paz grant from the Ministry of Culture, Lilia was a bit anxious. She had done interviews with the men who worked on the ships, expanded her photographic series, and even had a macho man printed, but she didn’t know who could help her design her photobook.

In that search, she found an interview with visual artist and editor Zully Sotelo from Aquí y Allá and decided to contact her. Zully says that she suddenly started receiving messages from “a stranger” on her social networks who needed her to make a photo book. After two weeks of periodic messages, they made a video call; she understood Lilia’s intention and her time and money conditions. With that in mind, Zully created a team with José Ruiz and Arturo Salazar from the publishing house Ediciones Réplica.

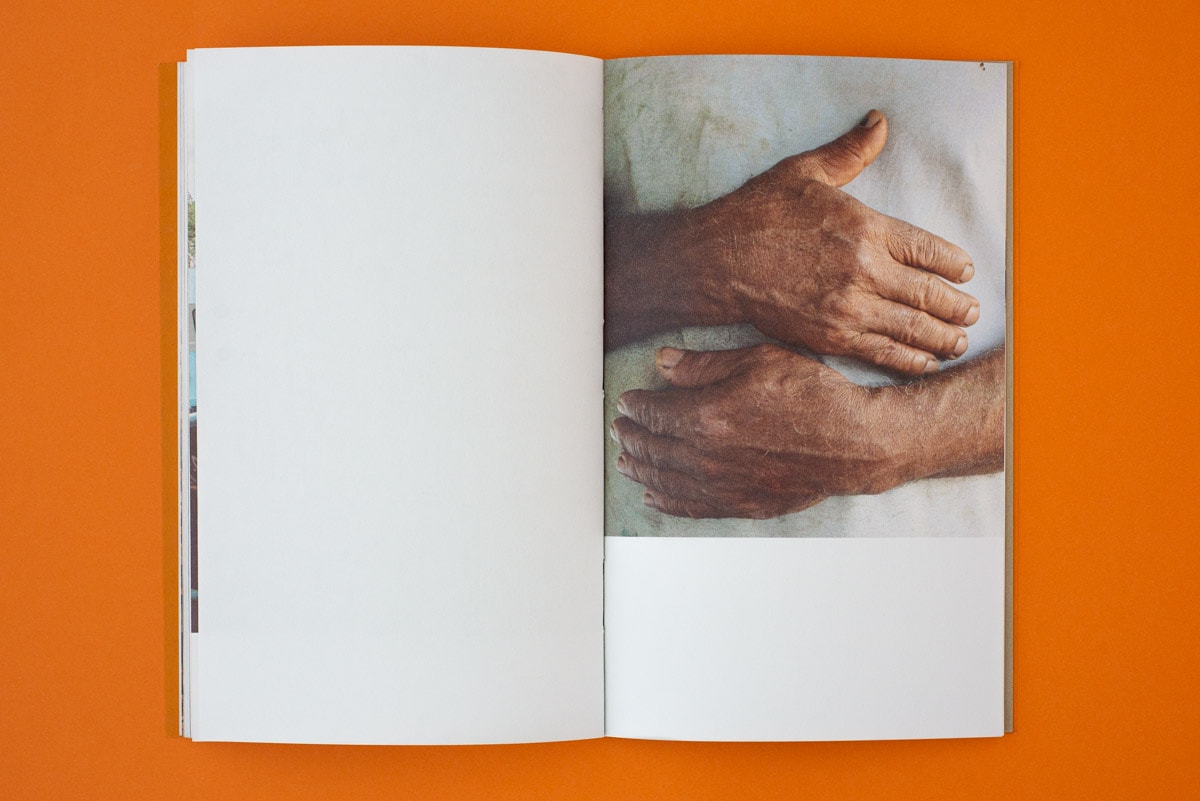

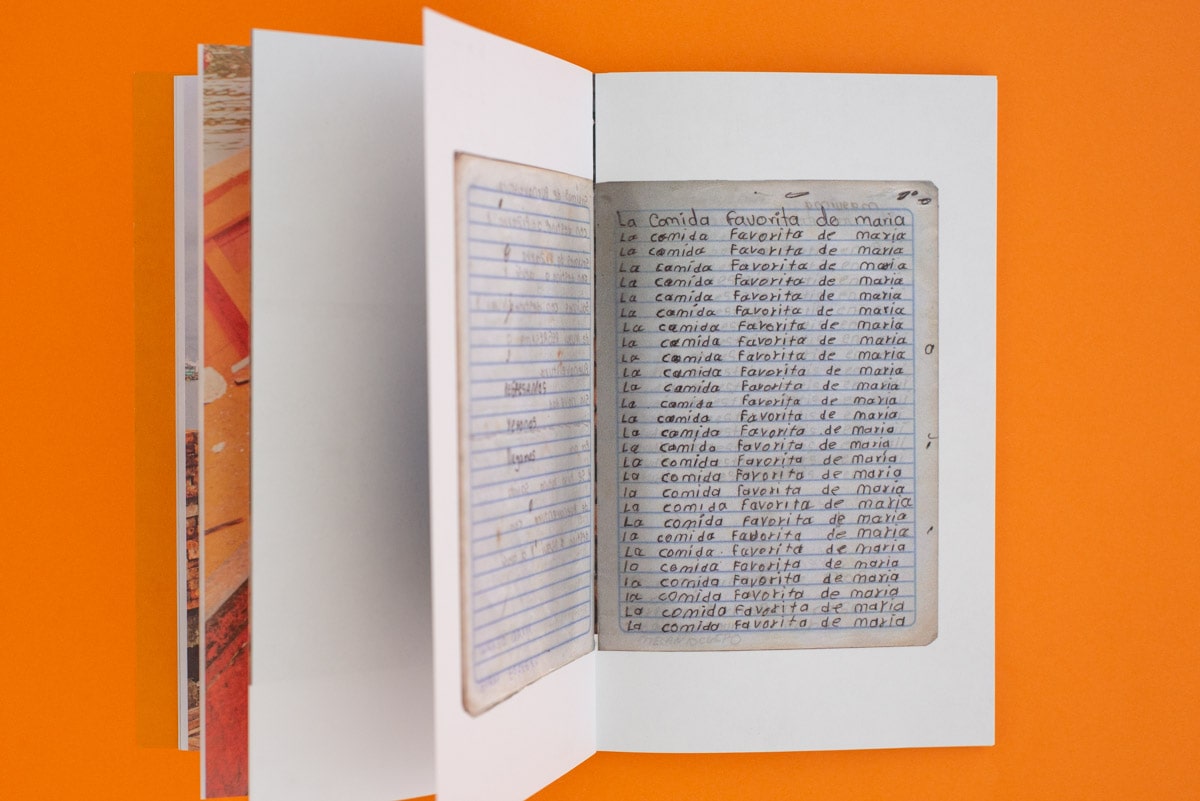

They created an archive with photos of Lilia, documents, articles about the shipwreck, interviews, and old papers of don Melanio. Among these documents was the logbook: his father recorded the details of the voyage in its pages, but it was also the notebook where he exercised his calligraphy. He learned to read and write as an adult and took advantage of his free time during the trip to practice. He would write the names of his children, the ports of departure and arrival, and the phrase that appeared most often: “we returned without any news.”

With the project underway, Lilia took more photos, this time portraits of the sailors. This process resulted in Regresamos con Novedad (we are back with news), which in Zully’s words, more than a photobook, is “a sea where they could navigate the stories, not only of my father but of the other men and women machinists who work on the coasting ships.”

The sequence of images immerses us in the journey along the Pacific coast, in that greenish-gray water and the overcast sky. We feel the swell and the ship’s movement on the water, moving images and meanings. The repeated texts of Don Melanio’s logbook accompany passages from Buenaventura to Nuquí, with no novelty. Of journeys that end up underwater. Of stories that speak not only of the various trades on the sea: but also of daily life, violence, the past, the future, and love.

As a sailor’s daughter, Lilia found beauty in the sea, ships, and destinies, some of them sad. As an editor, Zully found a story and an author full of energy and impetus to learn. As readers, we find unknown stories, although daily and intense, as sometimes is the swell.