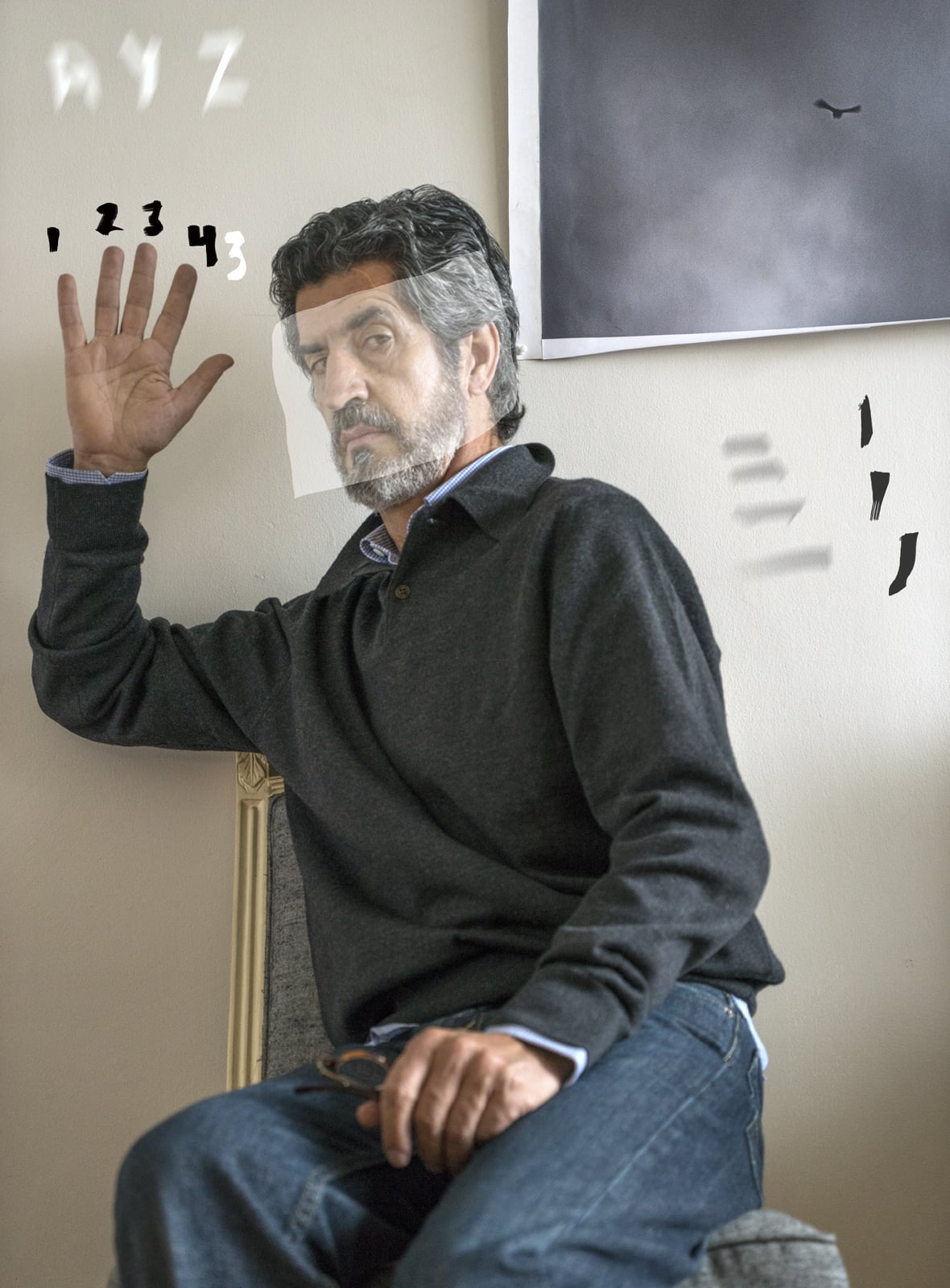

Close to the boom

In the mid-1980s, Pablo Ortiz Monasterio and other photographers proposed to the then director of the Fondo de Cultura Económica, Jaime García Terrés, to edit and publish a collection of photobooks. The main argument was that just as the Latin American literature boom occurred in the 70s, at that moment the photography boom would begin. They convinced him and the result was 20 photo books edited by Pablo. He now says that that much-heralded boom didn’t happen then, but now, with the implications of the digital revolution and access to social media, it is happening.

Pablo studied photography in England and when he returned to Mexico he began his career as an author and editor of photobooks. For him, it is one of the most interesting media to disseminate and display images. His best-known book is La última ciudad published by the Twin Palms publishing house in 1996. Pablo and Patricia Mendoza founded in 1993 the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City, years before he collaborated in the Consejo Mexicano de Fotografía. There they produce the Latin American Photography Colloquia.

Pablo, you have made several photo books. Did you start with La última ciudad?

No, my first book was Los Pueblos del Viento. The story is long, I studied economics and worked as a photographer. At the end of my degree, I decided to concentrate on photography, I moved to London, where I realized that books were an extraordinary platform to share photos. Three years later I returned to Mexico and started working at the Metropolitan University, I accepted a full-time position as a photography professor in the graphic design career and I was teaching photography and learning design and editorial production. During that time they looked for me from the Archivo Etnográfico Audiovisual that belonged to the Instituto Indigenista for an editorial project. We made seven books, one of mine, entitled Los pueblos del viento, about the Huaves, an indigenous group dedicated to fishing, something rather rare among the Mesoamerican peoples who were farmers. That was my first long-term project, I worked on it for 2 years.

In the eighties, we made “Río de luz” at the Fondo de Cultura Económica, a collection that became famous with an Ibero-American vocation. There we published 20 titles: the Spanish Josep Renau with his book American Way of Life, the Ecuadorian Hugo Cifuentes with Sendas del Ecuador, several Argentine photographers in Democracia vigilada, the Brazilian Miguel Río Branco with Dulce Sudor Amargo, the Mexicans Graciela Iturbide with Sueños de papel, Pedro Meyer with Espejo de espinas, Manuel Álvarez Bravo with Mucho sol, among many others.

We met four times a year with a very distinguished editorial committee: Manuel Álvarez Bravo; Luis Cardosa y Aragón, the great Guatemalan poet and art critic; the teacher Graciela Iturbide; Víctor Flores Olea, diplomat, politician, and photographer; Vicente Rojo, designer, and editor; Felipe Garrido editorial manager of the Fund. I coordinated the project, it was a very enriching and enjoyable experience.

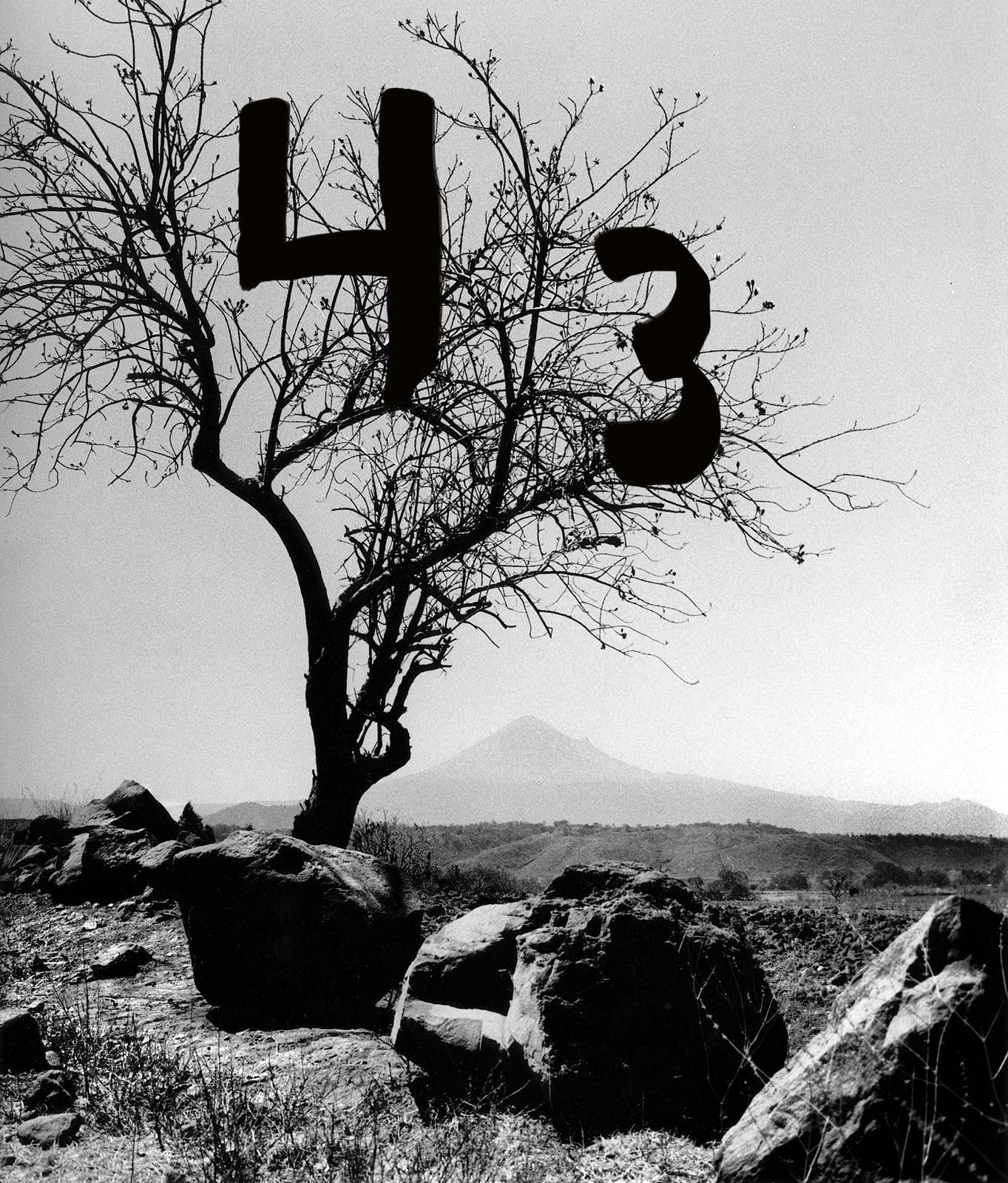

Los Pueblos del Viento – Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

I dedicated a decade to the Mexico City project, starting in the mid-eighties. In those years we photographers were very much focused on rural areas, we did photography on black and white film, direct, committed, with a political vision. But the city was documented by the photographers of the daily press. After my book on the Huaves I decided to investigate the tremendous city where I had been born and lived most of my life.

By those years, Mexico City already qualified as a megalopolis, always growing and changing. From when I started to when I finished the population had grown by three million, the city does not stand still, it never stops changing. For years I worked to build a global vision of the city. I certainly had a set of good and interesting photos, but it’s not enough to make a book. A catalog is a group of “good” photos sometimes with a theme one after another. In the book, on the other hand, the theme of the photos is very important, the meaning is constructed in the order that is applied to it and the images are linked, concatenated. It has a beginning, there is a development, and it has an end. In order to make a book, not only do you have to select the good photos but also use those that the speech requests: even if the image is not so good, it is a fundamental requirement to know what you want to pose and from where you look.

Over time I realized that describing the city is practically impossible and perhaps useless. It freed me from having to include buildings, parks and emblematic places. I concentrated on building the experience of vital and surprising energy that results from walking in Mexico City.

I made a mockup with photocopies pasted into a notebook and set out in New Mexico to visit Jack Woody, director of Twin Palms, a publisher specializing in photography with a formidable catalog and remarkable production quality. It was the middle of the nineties. Still, in those years the publishers when signing the contract gave you a royalty advance and I left that office with a check for $ 5,000. The book was impeccably printed in Kyoto, Japan in photogravure with two editions, in English with the Twin Palms logo and in Spanish with Casa de las Imágenes.

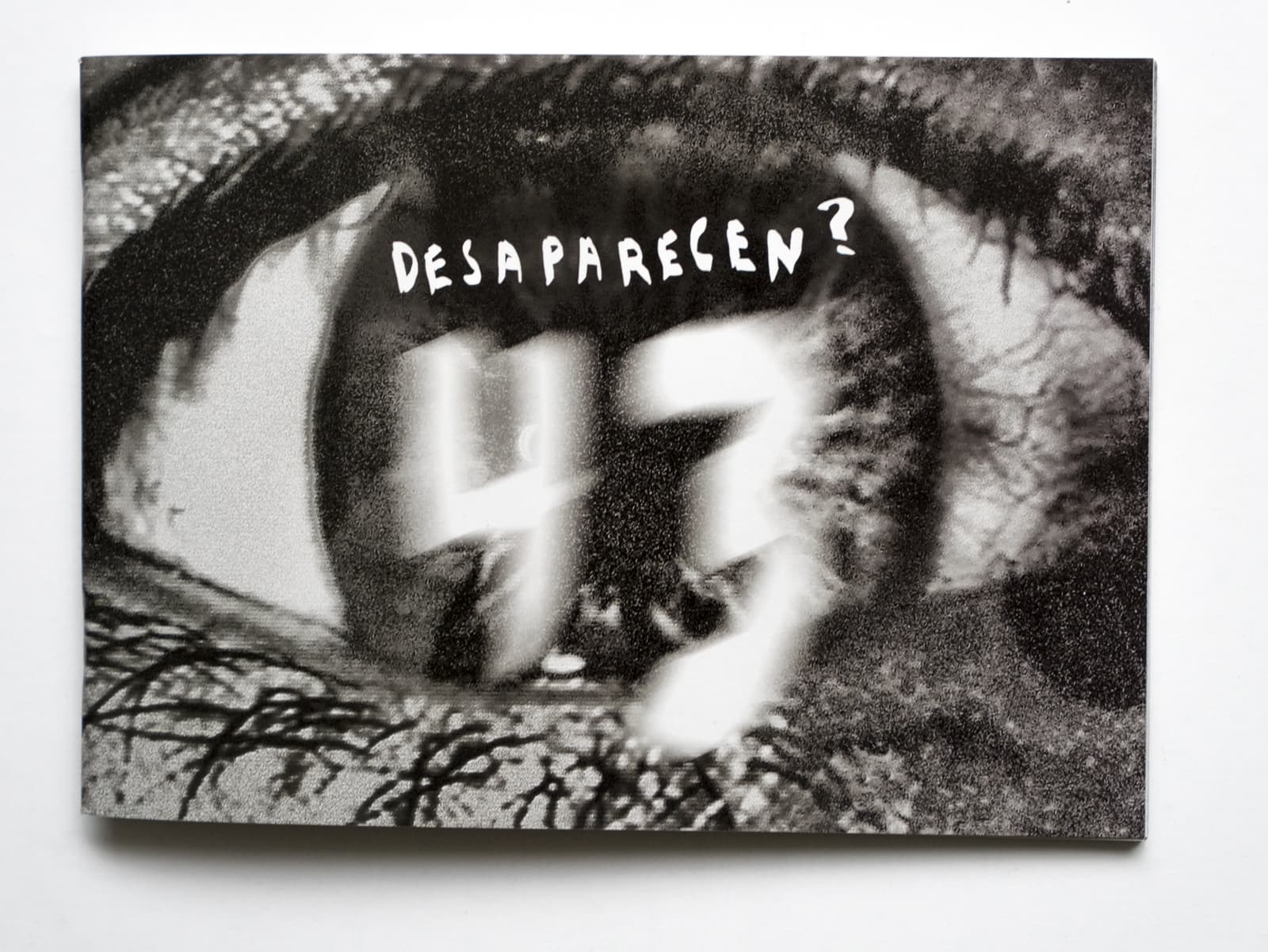

Desaparecen – Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

Some say that the process of making a photobook is a mystery. How do you build a photo book for yourself?

Well, there is no formula. Without a doubt there is an intuitive part, that one does not know exactly why and you are making decisions that take you to places that you had not foreseen. But if there is a methodology that can help to have a good result from a wide universe of images, put together a short set with a specific order. The first thing to do is review the ensemble and be attentive to listen to the voices emerging from the ensemble.

In the past we used to do it with photographic copies, we threw them on the ground to look at them unfolded, today it is done on screens. When looking at large groups the photos speak. What kinds of things do they say to you? For example, there are many photos at night, I also detect varied animals and of course the work of the community. This does not mean that we should do a chapter on animals, another at night and another on community work, the process of listening to the voices allows you to understand the whole and ideas of how to group them also arise.

Without a doubt, in a good photographic book, the beginning and the end are fundamental. Powerful photos, with a lot of energy, must be managed, knowing how to place them so that the book has a climactic point, and that it flows beautifully. In that sense, visual books resemble music, they have rhythm and there are movements or chapters.

It is important to think about the fundamental unit of the book, the two pages, that while you are looking at them you cannot see the rest. That unit can be occupied by a double-page photo or two photos or four or many, this will allow you to set the rhythm of the volume.

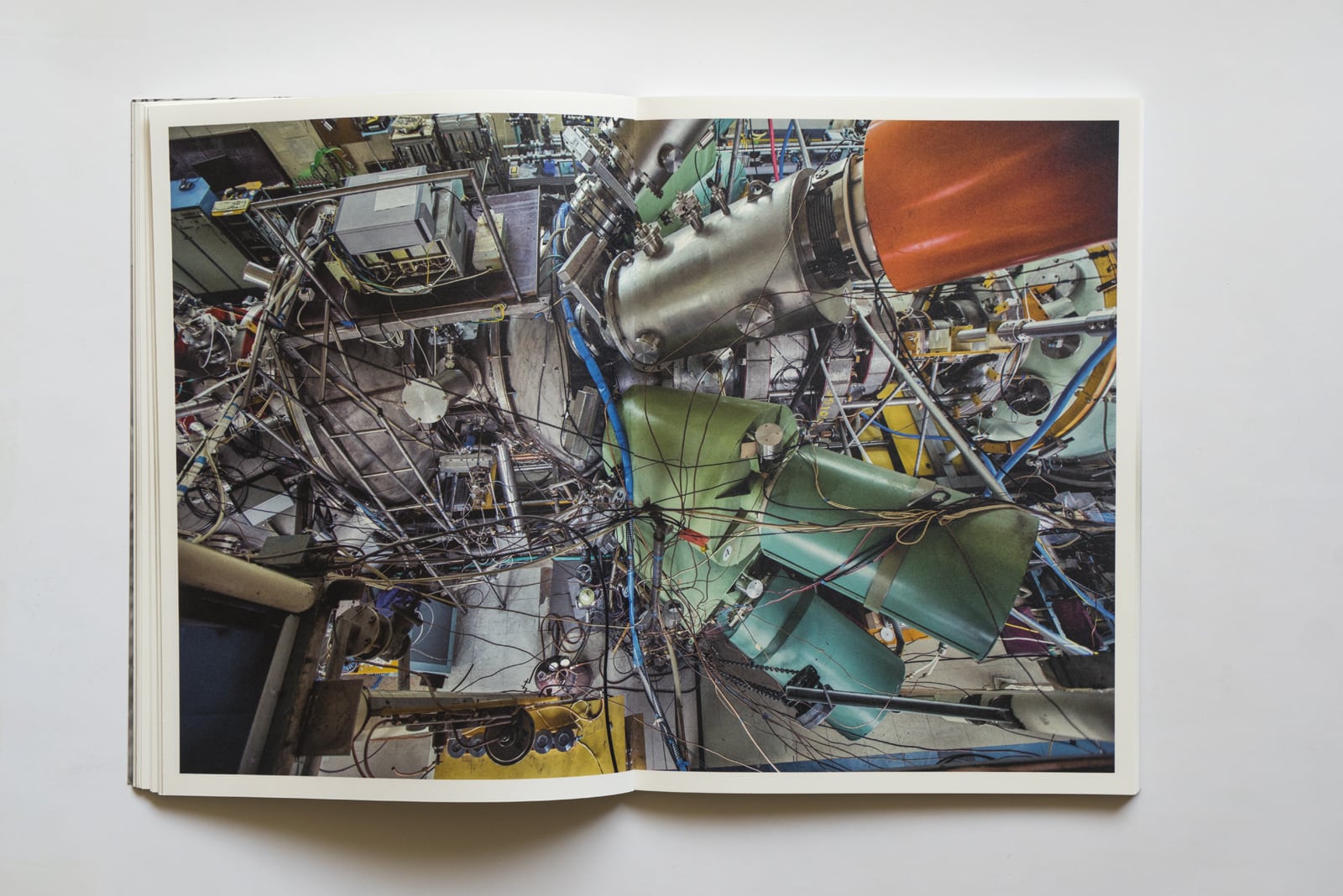

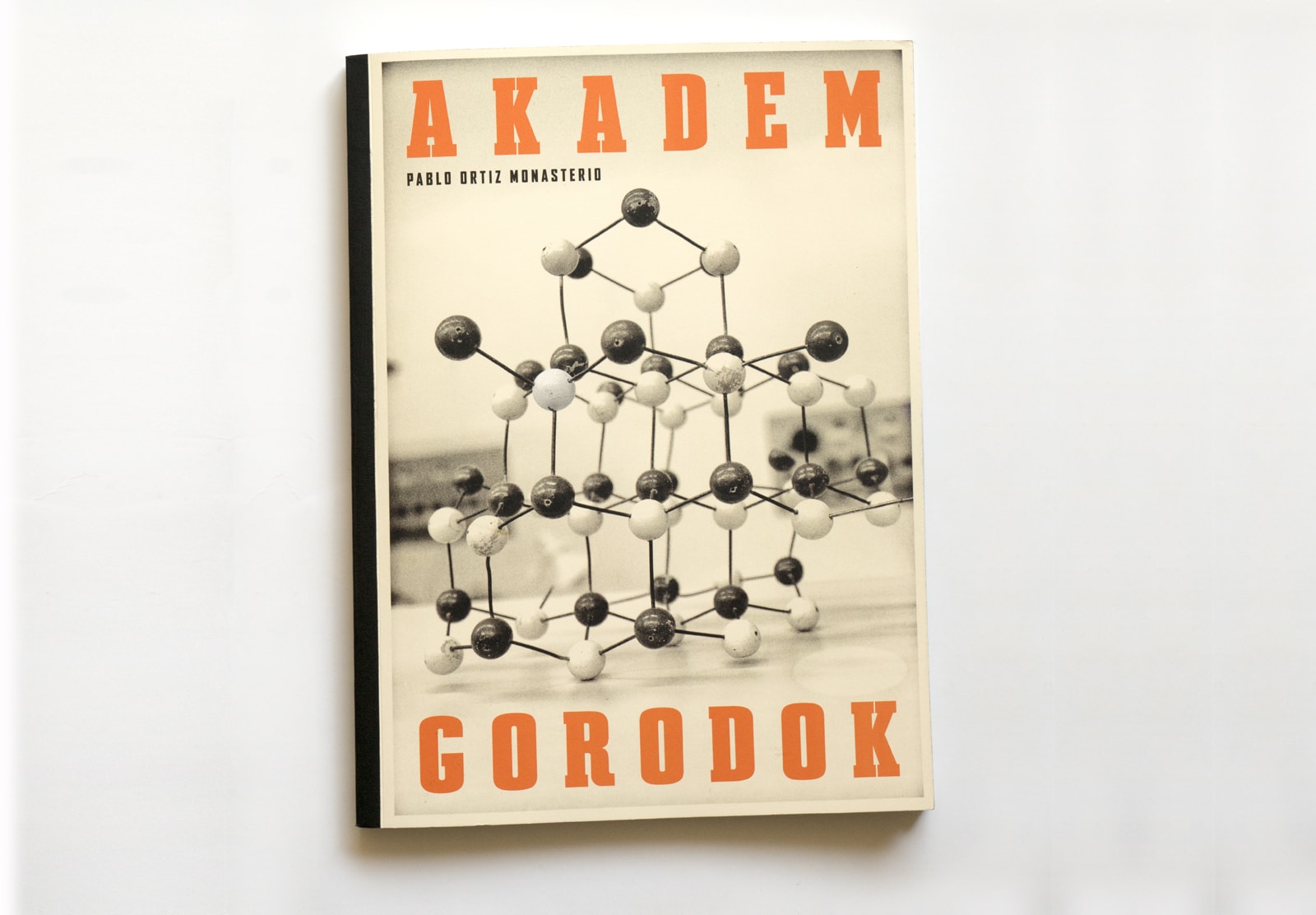

Akadem – Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

Akadem – Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

You were part of the Latin American Photography Colloquiums, how was that experience?

When the Colloquiums I was a kid. I was part of the Consejo Mexicano de Fotografía and from there they organized themselves, the leading figure in all that was Pedro Meyer. It was very interesting to get to know the photography of Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Argentina, Paraguay, Brazil, Chile and others. The truth is that photographers are not necessarily good speakers or theoretical articulations, but the Colloquia were a great window, we only knew Latin American photographers whose books or exhibitions reached New York, Paris, or London.

The colloquia were spaces that generated a Latin American consciousness that we did not have before and that now with social networks, it is natural to us. They were the first steps, we did not imagine what social networks would bring, and their relationships would occur horizontally without having to join organizations such as the Mexican Council of Photography.

Desaparecen – Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

Desaparecen – Pablo Ortiz Monasterio

Remembering all that history, how do you see current Latin American photography?

When we did the Río de luz project, in the second half of the eighties and nineties, we presented it to Don Jaime García Terrés, with the idea that a Latin American boom was coming, like that of literature, but now in author photography.

We made the collection with 20 books and there was a little boom. Sure, we publish very interesting works, there are beautiful books and it is probably the only Latin American collection in the strict sense.

With the digital revolution and the democratization that it brought, it can be said that today there are more than one billion photographers on the planet if there are 7 billion phones that can take photos. Let’s say that only one person in seven takes photos repeatedly, we have a billion photographers. This has meant that throughout all of Latin America a huge number of photographers have emerged, some very interesting, who are doing formidable work and that we can see on social networks. Democratization also occurred in terms of gender, probably the best photography in our countries is made by women. I am convinced that today we are closer to that Latin American photography boom than we were selling more than 20 years ago.