Andrea Jösch: escape from the unique image, place yourself in the territory

When a group of thinkers and photographers began to edit the South American photography Sueño de la razón magazine, many people criticized the choice of the name. The magazine is so named not because its editors believe there is a Latin American or South American way of photographing but as a way of planting a flag. “The political gesture of appointing ourselves is important to defend that political territorial exercise of the place from which one speaks,” explains Andrea Jösch Krotki, one of the editors.

For Andrea, talking about Latin American photography is a form of political recognition that implies reviewing and recognizing “our ways of seeing and doing”. She learned photography when she was very young, like many, she fell in love with the magic of the darkroom. She worked as a freelance photographer until her life began to demand more stability, and she found a place in a visual arts school. For more than 15 years, she has dedicated herself to teaching, researching, and editing and assures that it is one of the most wonderful things that have happened to her because they distanced her from a type of photography that no longer interested her.

Andrea, who in her presentation declares to be a “policy for the dissemination of South American photography, rooted in principles of integration.” Currently, she is the guest curator of the second version of the MUFF Photography Festival, of the Montevideo CdF Photography Center.

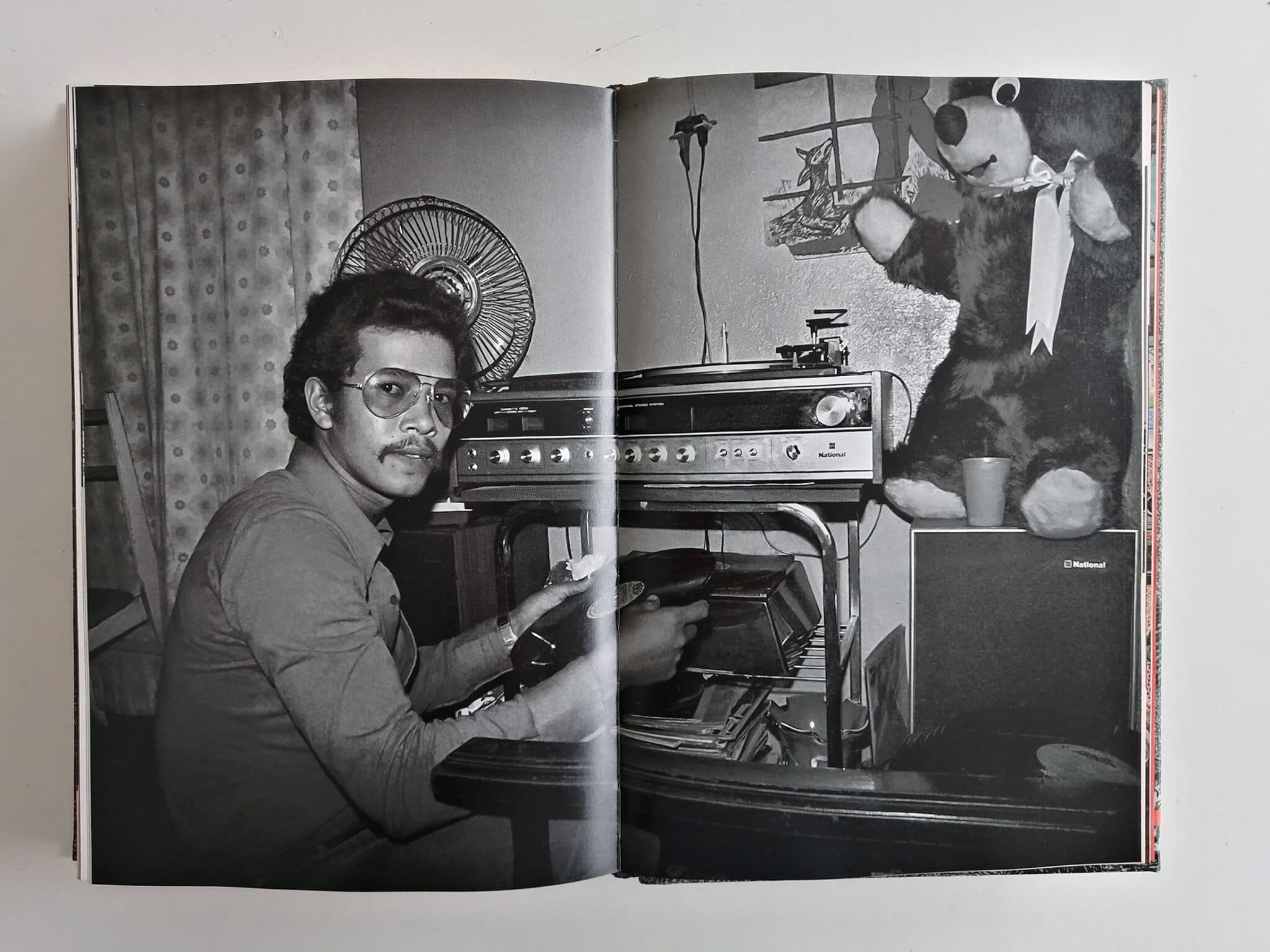

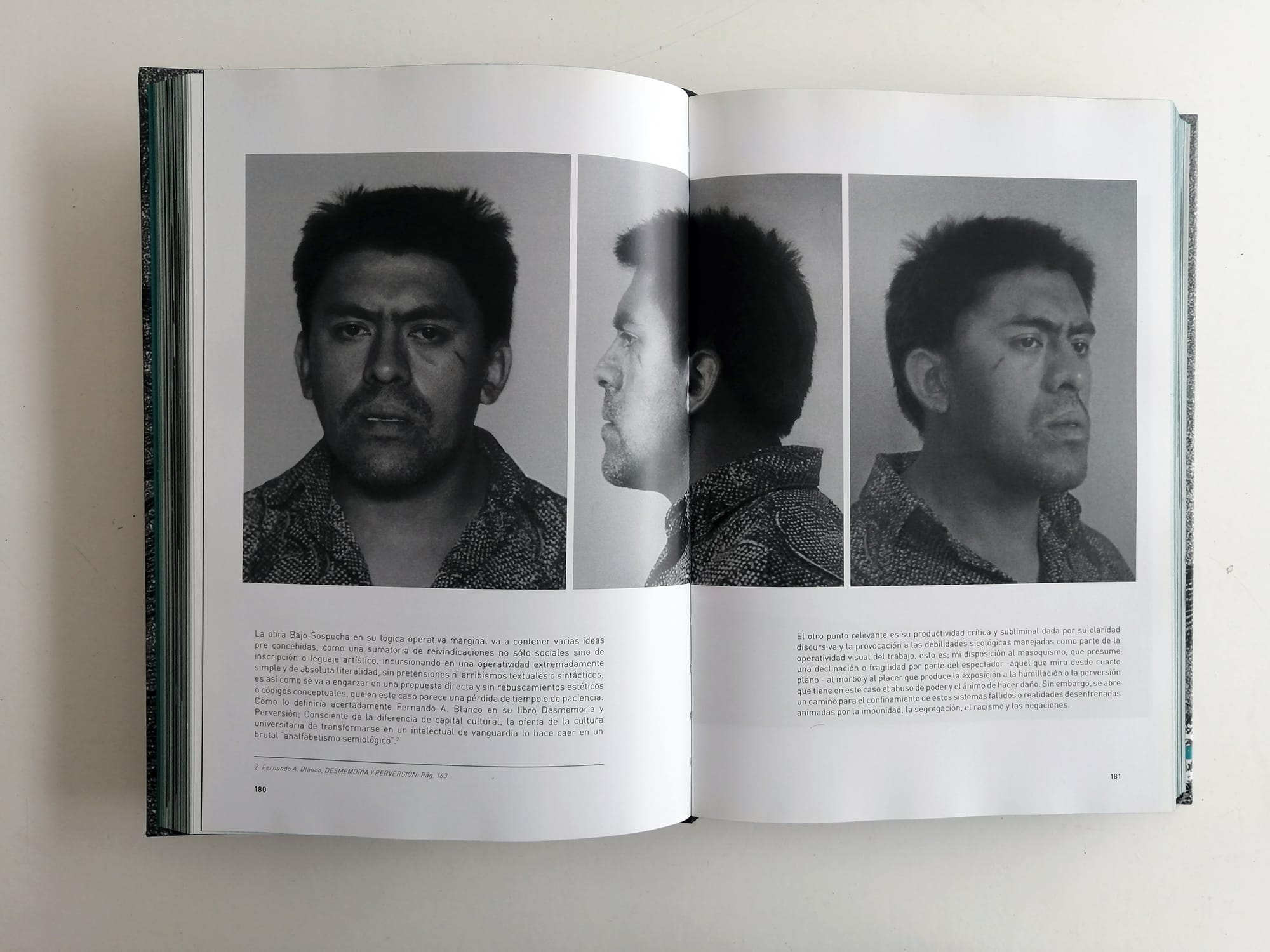

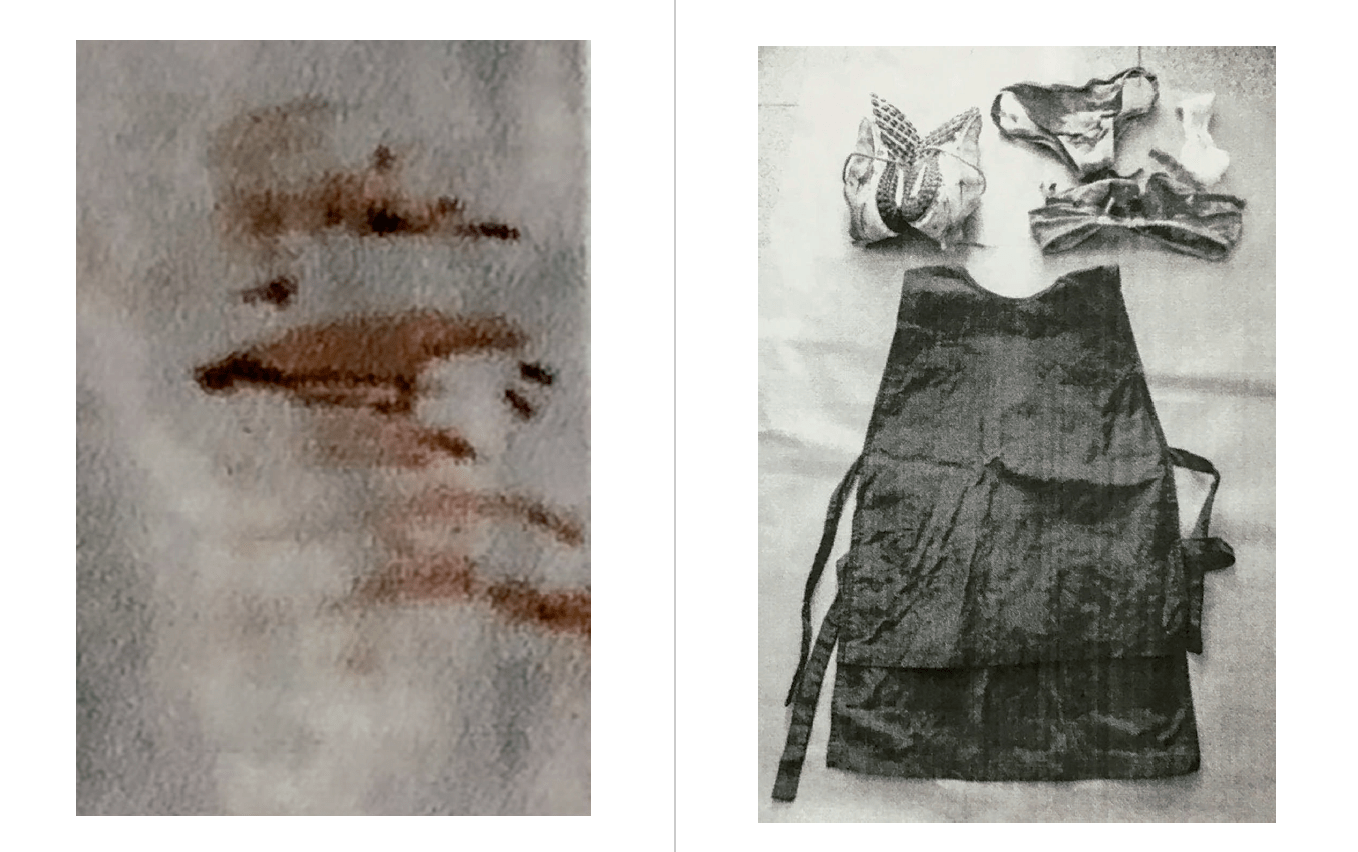

Bajo Sospecha. Fotografías y texto Bernardo Oyarzún. Sueño de la Razón Tomo II Editorial Metales Pesados (2013, p.180-181)

Every time I feel more like a teacher, I love the exchange of knowledge. And there, I have two clear positions. I think we haven’t recognized the weight images have at a formative level, I mean all levels of formal and informal education. It is very curious because we live in a world communicated through visuality and there is no interest or critical reflection to understand that relevance. If we want to transform the world and our relationship with others, we have to start by understanding that the misuse of images, especially for advertising and propaganda, has been disastrous. It allowed the construction of a single official-heteropatriarchal story that it left out (still does) the diversity of all other possible worlds.

Second, and there I put myself Camnitzian, a good pedagogy of listening, critical and reflective is needed. That is the only one that allows us that diverse, horizontal, effectively democratic construction. When I do classes or workshops, I reflect on that. All of us who make images or think about images have a responsibility to know what images we are launching into the world and what are the relationships and responsibilities with their social, political and territorial contexts.

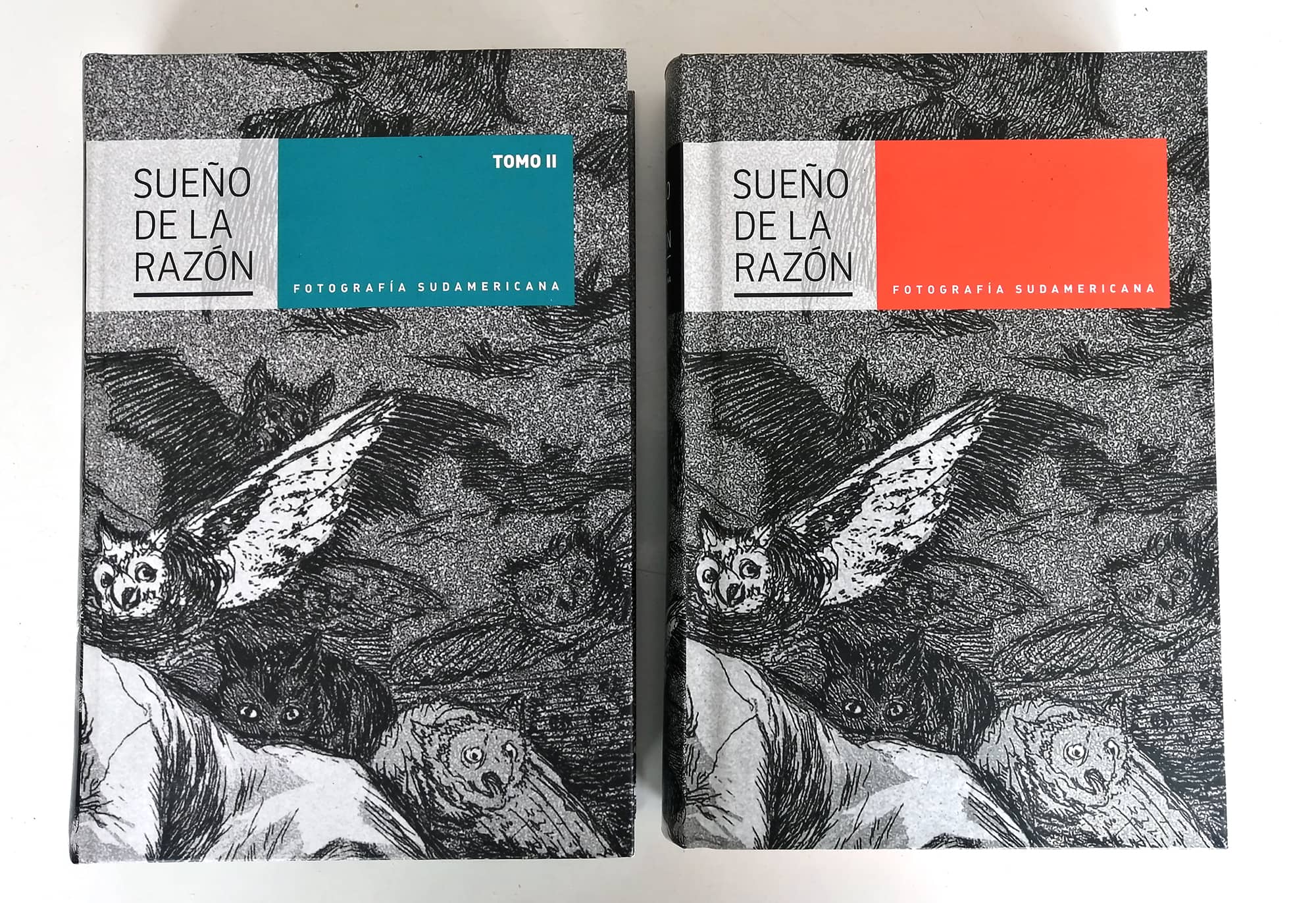

Portadas publicaciones Sueño de la Razón. Fotografía Sudamericana. Editorial Metales Pesados Tomo I (2013), Tomo II (2016)

For me, art is not a transaction of objects or photobooks. The objects, the final images, or the books are consequences of a reflective exercise. I am not against that, it would be absurd since they are the material forms with which artistic proposals circulate, but I believe that they should not be the ultimate goal and that this is a part of what the arts serve and propose. I am not interested in the image for the image’s sake either.

The arts serve to put questions in the world and not only to be contemplated. It seems to me that many people are eager to be recognized within the field of photography, without understanding that photography and visuality are transdisciplinary, they are involved in everything we do daily. There has been an enormous distance between the research processes and the questions: why I do what I want to do and who I want to communicate it to; a professional career often emptied of critical sense.

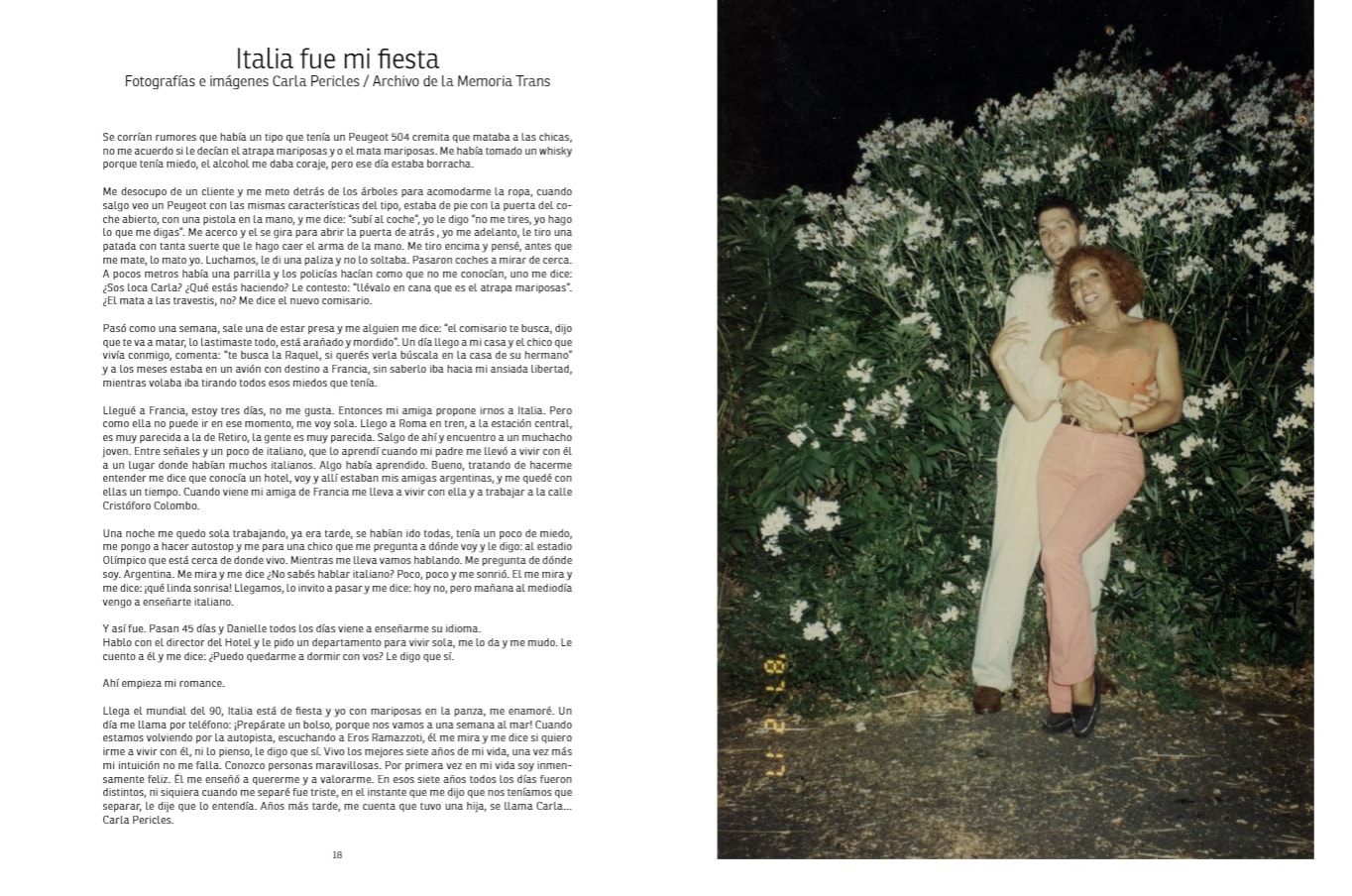

Italia fue mi fiesta. Fotografías e imágenes Carla Pericles / Archivo de la Memoria Trans. Revista Amor (in) Certo. Sueño de la Razón. Fundación Sud Fotográfica (2019, p.18-19)

We have learned in school training, through advertising, the media, school books, etc., a single Eurocentric and, later, North American story, misnamed “universal”. The terrible thing is that we assume it by force or by the conviction of wanting to “be modern” as if it were our history, but it is not, those are not our territories and nor our worldviews, nor our way of approaching the gaze. So, when one still wants to sustain in the 21st century an aesthetic philosophical exercise that does not correspond, and that has also been the one that has governed a single ocular-centric way of looking, we fall from grace.

One could argue whether indeed all those formal laws that we are taught in photography technical schools about the golden zones or the law of thirds are also a political question. A posture that implies posing individually in front of the world with a biased vision, which insistently seeks a unique photo that represents the history of the world. For example, now, they are waiting for the photo that represents and synthesizes the pandemic. It’s ridiculous. Why do we need to question all the experiences of multiple cultures and diverse territories in a single image? That is why the construction of new narratives and research exercises are necessary to break visual inertia. It is necessary to understand that the single truth does not exist, less in the images; but there are many different approaches to the realities that we live from different territories, human and non-human relationships, political considerations, myths, historical wounds …

The great photo infuriates me. I cannot understand how for so many decades we have believed or wanted to belong to that construction of the world. I think it has to do, among many other things, with a lack of critical reflection regarding visuality and what it represents of who we are or who we want to be.

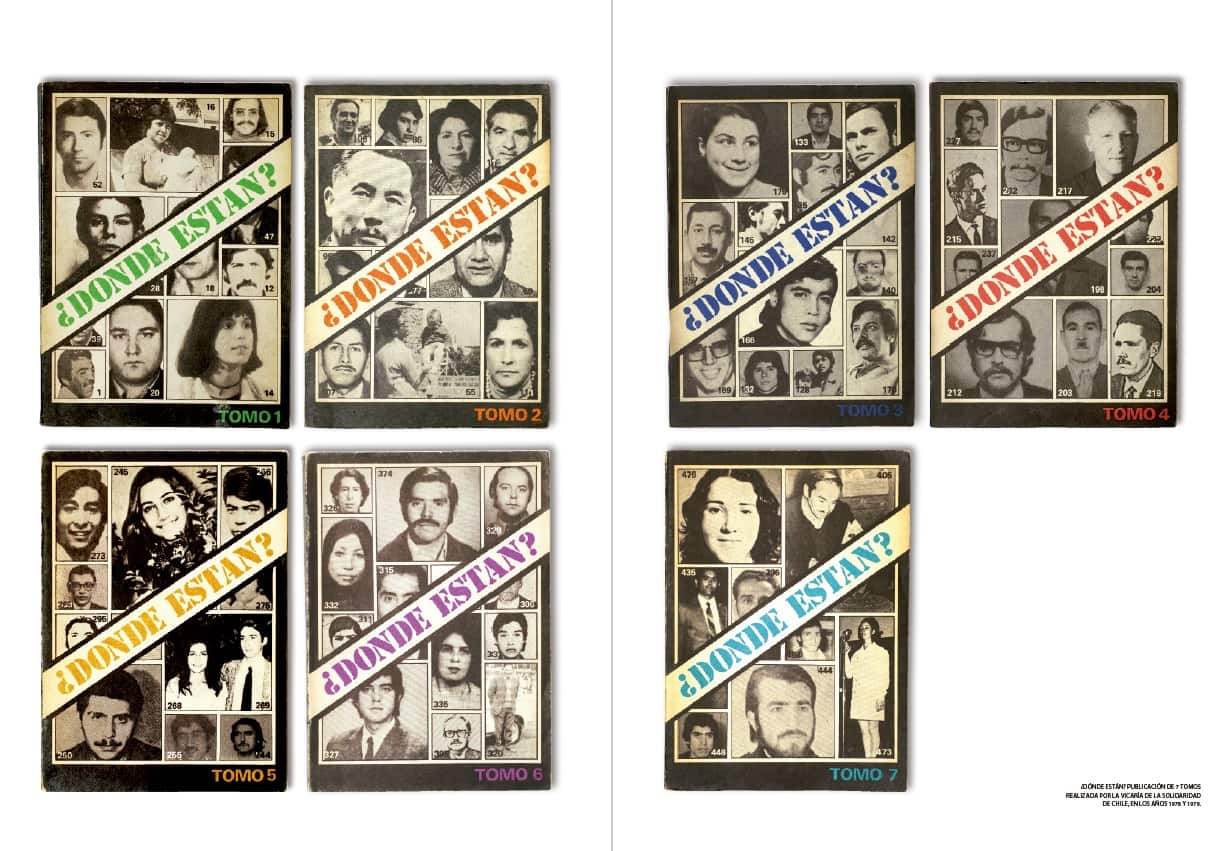

¿Dónde están? Texto Cesar Barros. Luta e Poder. Sueño de la Razón. Fundación Sud Fotográfica (2020, p. 72-73)

Yes, but every time it opens more and more. I also believe that both photographers and people who think about images should broaden their spectrum and their comfort zone a bit and understand that this is also relevant in other places or spaces for knowledge exchange. You have to know if you are working primarily for the market or the expanding field of reflection on visualities and their inevitable relationship with social, community, political, environmental, biographical conflicts and contexts …

Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, in her book Sociologia, la imagen y otros textos, comments on this question of looking, saying for the Quechua people they do not “look” only with their eyes, but that it has to do with being physically in space to relate to through listening to the body with what is in front of you, taking into consideration the initial and deep interest in what you want to know. So not only is it an ocular-centric problem, as has been the western history of images but precisely to establish a dialogue the conscious presence of the body is needed. She also says that to investigate, the first thing one has to do is find out and pry before communicating. This has to do to be in the body and not only exercising an observation from a distance, both intellectual and formal.

There are already contemporary photographs that do what Silvia says, that is, there are photographers who are concerned with the dialogue they can establish in spaces and reflect on the transformations of both space and themselves.

Yeah right. There are beautiful projects in all areas. From the community, for example, there is the recent work of the Ruda Collective on food in times of COVID-19, the result of which was a website that brings together the different approaches of several Latin American photographers in This is not a chain.

There are also other views from management. Like what the CdF does in Montevideo. I was invited to curate the second MUFF festival, along with a beautiful team of people who are working as activators, including Mônica Hoff, Gisela Volá, Valentina Montero, Maya Goded, Alexandre Sequeira, Luis Camnitzer, and the entire team of affectionate people. Professionals from the center: I point out affection because it makes a difference. The CdF realized years ago that events did not delve into the processes, that we got together for two days and edited everything quickly to reach a final object that no longer works. This festival lasts two years and people spend a year and a half in a long process of collective reflection. The results and the construction of networks of affection are very different.

Femicidas. Fotografías y texto Rueda Photos. Mal-estar, resistência, transformação. Sueño de la Razón. Fundación Sud Fotográfica (2021, p. 124-125 )

It is that the arts are a form of knowledge. But knowledge from the arts is built in practice. And explain that to a system that has become a market for the production of indexed papers or publications that enter a pre-established way to enter a market is hard and disastrous.

The field of artistic research is relevant. If we talk about the university or school education, it is one of the few spaces whose function is to ask questions to the world and not necessarily answer. And it is one of the only or few fields that shows the error and the finding of its process. Normally, in other fields of knowledge what is shown are the successes or the good results.

But you think that ordinary viewers see it that way, they understand art as a form of knowledge.

If formal education, hours of philosophy, and art are taken away, it is more difficult for it to happen. In addition, several cultural institutions have a deficiency, they have become mausoleums of objects, rather than schools of mutual learning. Furthermore, one should not even try to make other people – the public – understand what one wants to say. What one has to try is for these other people and ourselves to ask questions about this dialogue in common. Because if we want to teach or think that the other understood, we are still thinking we have the truth. We are small contributions to expand or allow other possible worlds.

In that sense, that education we were talking about at the beginning would still be needed to achieve an effective critical reading of what is seen. Photography, much more than the other visual arts, carries with it this effect of truth or reality. Many times whoever sees the photograph believes that there is no greater manipulation in what he sees.

Dismantling is not so difficult with a pedagogy of images or visualities. The problem is that the power structures don’t want that. There are no approaches to visuality in schools, although it is fundamental. There is a Chilean philosopher named Andrea Soto who has just released a book that I recommend, The performativity of images (Editorial Metales Pesados, 2020). One of her thesis is that there is no overabundance of images, but rather a kind of saturation of identical images. That is why it is so important to create new images that effectively speak of the invisible, of the unseen. I agree with her because one always talks about everyone being a photographer and indeed the technology of the telephone has generated that we all take photos. But when you look at those images and put them side by side, they are the same, they are replicas, representations of an individual capitalist system.

The images reflect our way of looking at the world and it is super complicated because sometimes you see that condition of the corporality of the frame or the way of looking that replicates a terrible system. Many times they ask me if one can talk about Latin American photography, and there are many people against and many people in favor. I do believe that we must rethink our practices from our territory. That means rethinking our stories and telling new stories and the past that were not told or were told very badly.