The Metamorphosis of the Archive

Marina Feldhues is a Brazilian photographer, tarot reader, visual artist, professor, and researcher. She holds a master’s degree and is pursuing a Ph.D. in Communication at the Federal University of Pernambuco (Brazil). She is the author of the books Catalog (2019), Photobooks: (in)definitions, histories, experiences, and production processes (2021), and And if…? Archives, photographs, and fables: listening and learning (2023).

By Maíra Gamarra

In this interview, we discuss your artistic and intellectual production, a body of work that explores the limits and possibilities of archives and the various languages of art as instruments to rethink and reimagine the present, past, and future. It acts within the interstices of coloniality, subverting practices that operate through the visuality of power, which routinely updates violence in different aspects of contemporary life. Marina encourages us, through artistic experimentation, to build alternative relationships with documents and art, considering the roles they play in sustaining coloniality—a living and active space, yet imbued with gaps and contradictions that can and should be systematically deconstructed and reconstructed for the invention of other ways of living and signifying.

Viagem ao Brasil (Journey to Brazil)

In many of your works, you engage with photographic and archival collections (family, public, and private), as well as newspapers, official documents, books, etc. By re-signifying these materials and their historical uses through creative and critical processes, you challenge the present and latent coloniality within these archives. From your perspective, what are archives, and what do they enable? Why did you decide to work with them?

Archives establish forms of knowledge that enable certain statements while obliterating others. I will share information specifically about archives as conceived and developed by colonizers and their descendants. These archives categorize documents in a hierarchical classificatory order from the specific to the general, stabilizing documents in meanings that adhere to them like a transparent second skin.

When we access these archives, we believe we are directly accessing their materials because we don’t see the discursive layer surrounding them. We are guided to read the materials according to what the archive’s classification system has already determined. Generally, this system reinforces the meanings attributed to social documents by their authors. I understand the author as the person who, in the social relationship from which the document emerges, is considered by the archivist to have greater decision-making power.

For example, a 19th-century photograph of an enslaved black woman only proves that the woman existed at the time the photo was taken and nothing more. The photo is a testimony to her existence and the social encounter from which it originated. However, in colonial archives, this image will be labeled as “racial type X,” a label that overlays the photo, merging concept, image, and referent. In this dynamic, the person photographed is not treated as a subject, as an individual, but as an object, a character illustrating the ideas of an author, the photographer, or their contractor.

When accessing colonial archives, whether institutional or diffuse on the internet, I immerse myself in this way of knowing and relating to social documents and people. To work with archival materials, I always need to shed this second skin attached to the documents (whatever they may be) to step out of this place in automatic agreement with the discourse of the “author” or archivist guided by archive access protocols.

Only then can I look at the materials and reimagine the social scenes that gave rise to them—the social forces in tension, the possibilities of action for the protagonists in those encounters whose product is the archival document that has reached me.

Thinking about these archives, I can answer your question by saying that archives allow me to understand life trajectories, social relationships, and the forces at play. It allows me to recover narratives and knowledge different from those endorsed by the archives themselves. All of this through research on inscriptions, traces, and radical imagination, carried out in the company of many of those portrayed and those attempting to think about the world differently.

I did not decide to work with archives; I simply lived among them to the point of saturation where it became impossible not to respond to the demands of those who haven’t even been able to rest in peace because they are still fixed in discourses of violence. This, in turn, continues to feed the social imaginary of my time, materializing violent realities of today with an eye toward tomorrow. Working with archives is always a matter of the future.

When I was born, a collection of comics awaited me. Then I started collecting letterheads, stamps, books, diaries, agendas, photobooks, until I became the guardian of my family’s photographic collection. In my academic research for my master’s degree, I studied ways of understanding photobooks. The classificatory, archival way is one of them. At that moment, I began to understand the limitations of this type of knowledge and its extremely violent implications when applied to social relations.

For example, I began to observe the social classifications present in my family collection. My birth certificate lists the term “dark-skinned.” It is a racist term, expressing the hierarchy of color, colorism, as State policy in the year I was born, 1982. So, my birth certificate not only attests to my birth for the State but is evidence of the structural racism operating in Brazilian society that year. If I compare it with the present, do I find ruptures? Continuities? Changes of course? On what social scale?

Viagem ao Brasil (Journey to Brazil)

Working with archives inevitably involves thinking and talking about history and memory. Both are words, categories, and traps, but they are also spaces from which art and photography operate. They are concepts that can open up to the manufacture and reconstruction of meanings and directions (future?). I would like to know how you understand and approach these two ideas in your work.

For me, history is nothing more than a colonial disciplinary tool. It serves to create winners (authors, subjects, whites, civilized) and losers (characters, objects, non-whites, savages, etc.). It has a specific temporal, linear, and evolutionary form that is not consistent with anything other than the capitalist/colonial world imposed by military and symbolic means on the planet’s populations.

I am interested in trajectories that intersect, bifurcate, entangle, cross, compose, and decompose occasionally. Trajectories are movements of life. We are recreating our lives all the time; every past, present, and future breaks down and recomposes in different configurations within us. Times can coexist simultaneously.

That’s why I believe it is so important to care about how we know the past. It is well known that forgetting is one of the main tools of capitalist/colonial domination. But colonization also acts by implanting memories manufactured from the perspective of the “winners.” These distorted memories often harm the coexistence of different ways of existing and inhabiting this planet. If archival documents are not neutral, let’s not think that our memories are.

In my work, memory and imagination go hand in hand. I can imagine what my repertoire makes possible in its combinations; that’s why I’m always interested in other knowledge. That’s what feeds my imagination.

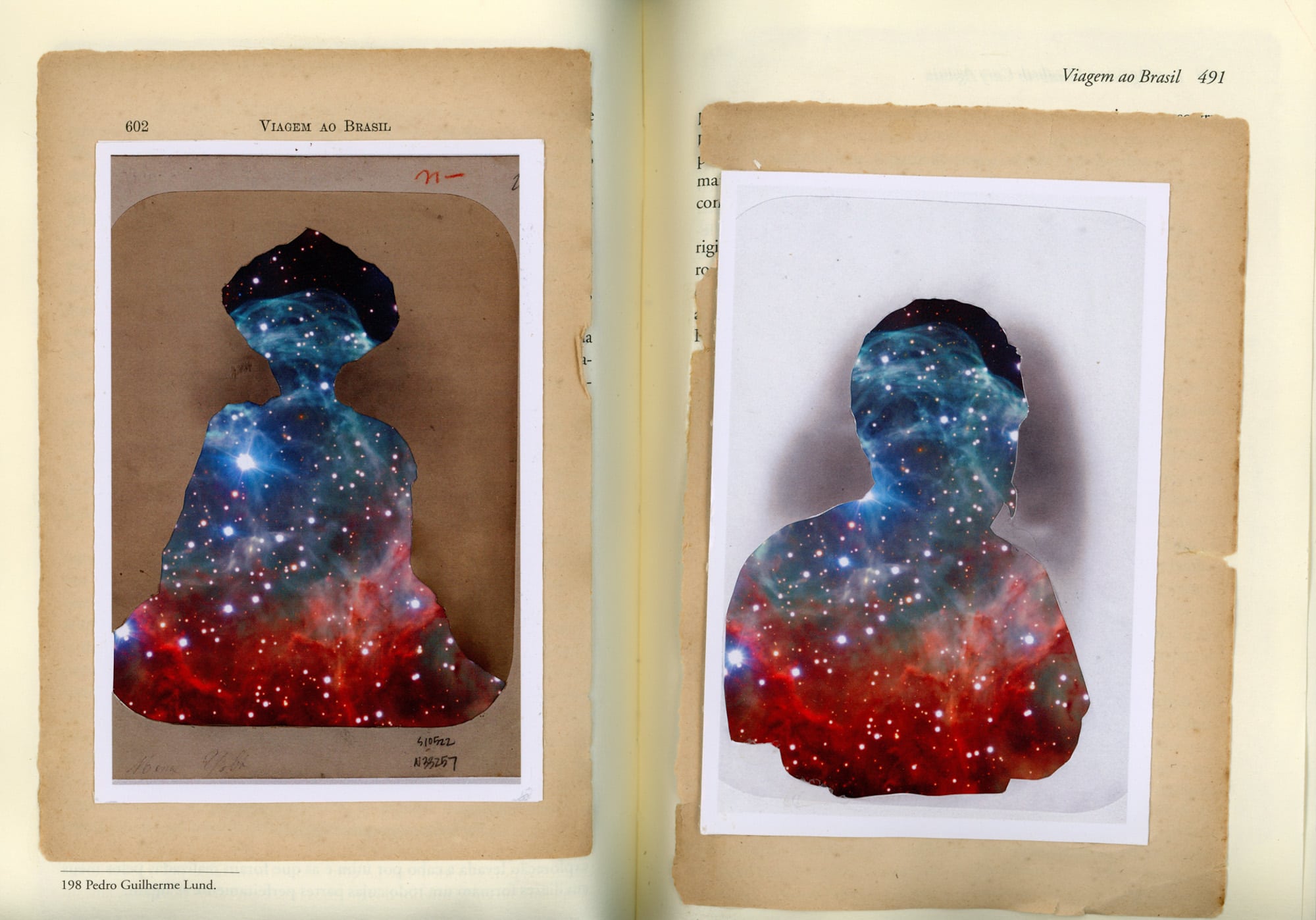

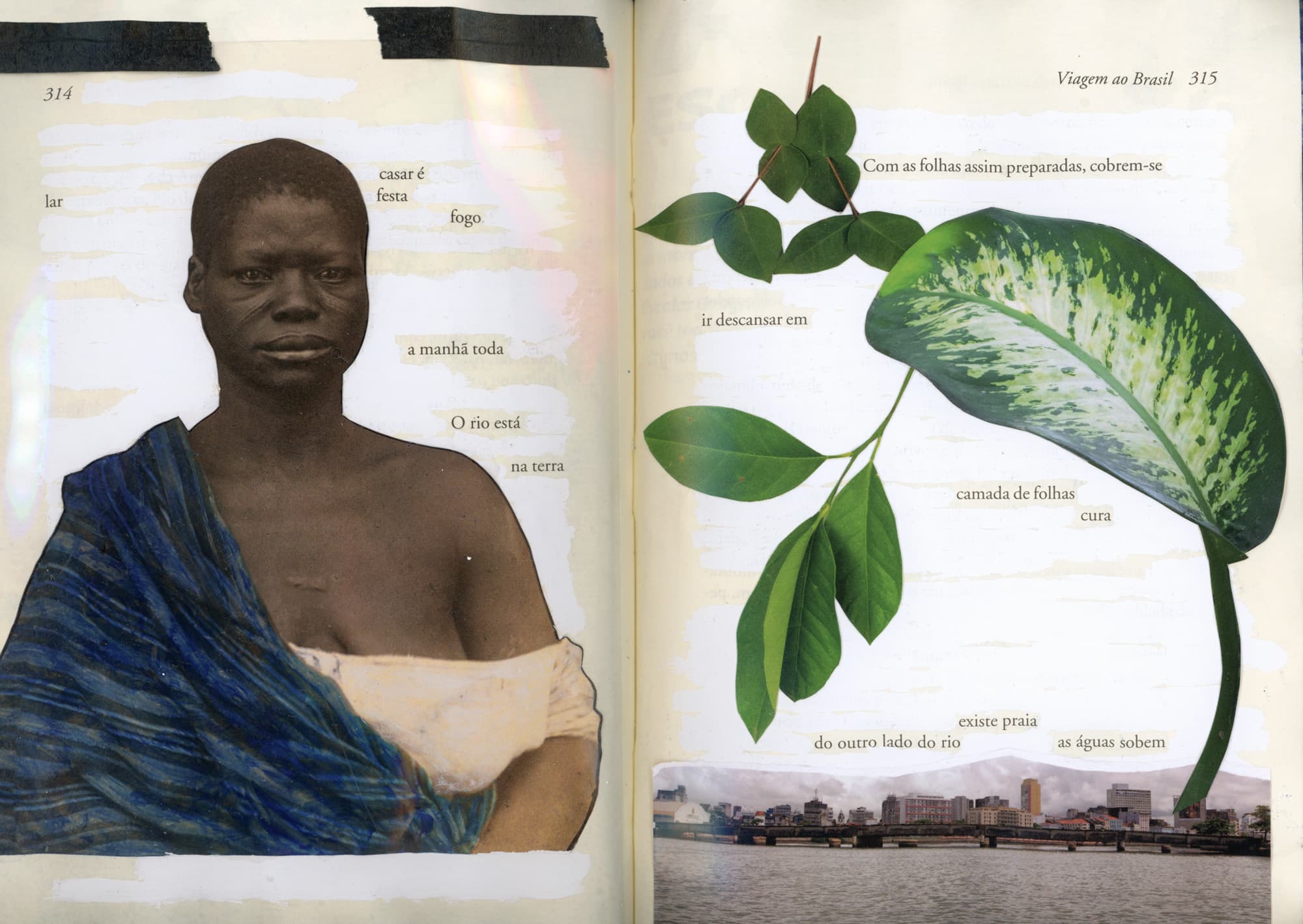

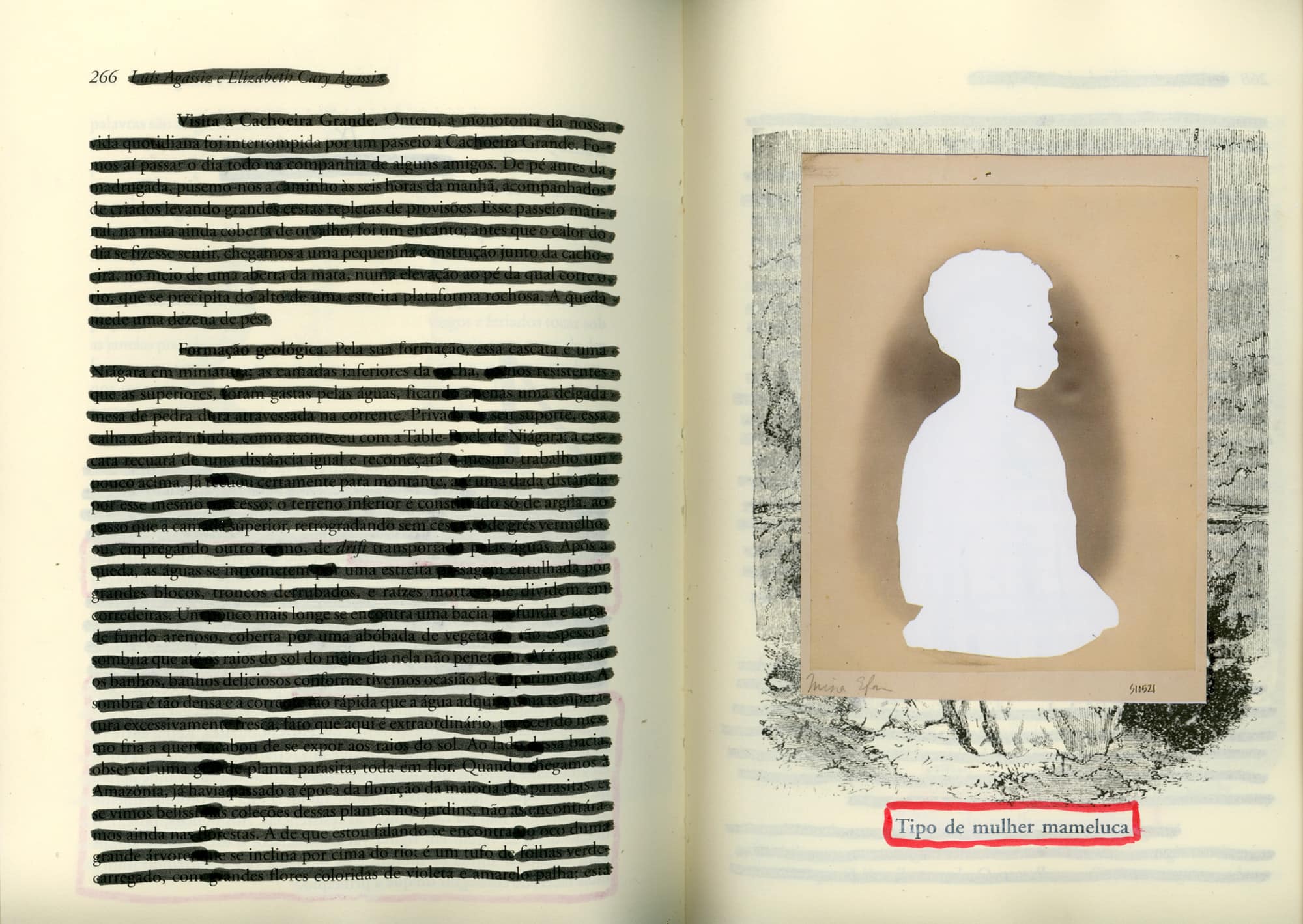

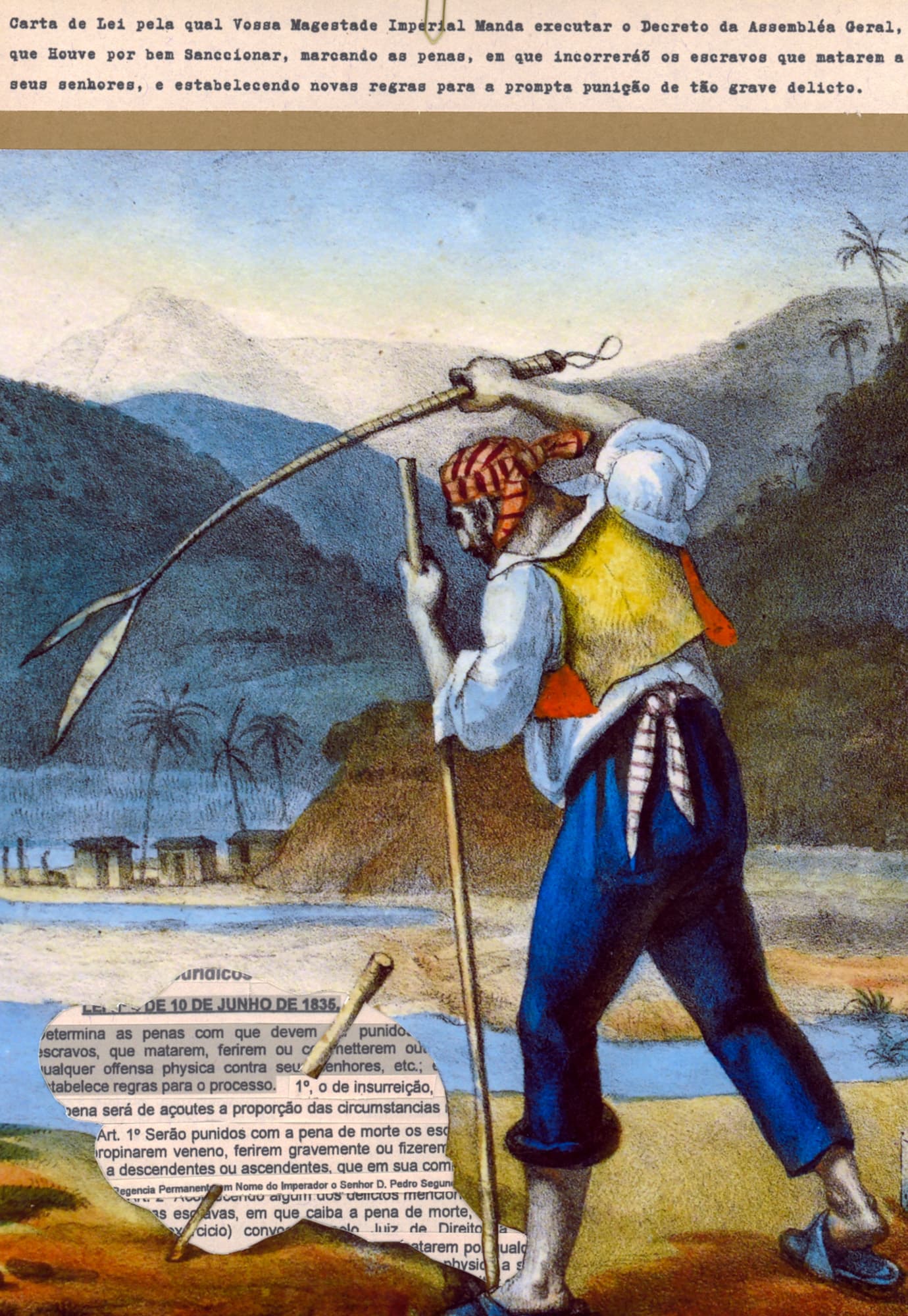

I’ll talk about a specific work. In the artist book “Journey to Brazil (1865 – 1866) [2019 – 2023],” what I do is overwrite the narrative of the original book “Journey to Brazil (1865 – 1866)” by Louis Agassiz and Elizabeth Agassiz with collages and texts (reviews, autobiographical essays, poetry, interviews, quotes) produced in the company of each of the people photographed during the Thayer Expedition, the name by which Agassiz’s journey was known. As we know, the expedition’s goal was to photograph blacks and mestizos to scientifically prove the inferiority of their race.

So, I requested the photographs taken by August Sthal in this expedition from the Peabody Museum at Harvard, digitized in high resolution. I had to write a project in English and wait almost six months to obtain approval and access to these photos. Along with these photos, I am overwriting the narrative of the book “Journey to Brazil (1865 – 1866),” published in 2000 by the Federal Senate to commemorate the “discovery of Brazil.”

It consists of 516 pages with various collages, texts, photographs, and maps proposing alternative narratives for the book. The collages engage with the original book’s narrative, presenting moments where I expose the narrative violence of the original book and others where I make its reading impossible. There are also moments where I overlay collages about the African diaspora, the Atlantic crossing, my relationship with the sea, the mangrove, even access to the archive and the image classification system.

Regarding portraits of “racial types,” what I try to do is saturate the stereotype through various collages with these photos and with my photos (since I represented myself in their poses). I attempt to question how we look at naked black bodies, whether for scientific purposes, testimony/voyeurism, erotic pleasure, medicine, or spiritual connection. Also, to question what these bodies can do beyond the discourses that attempt to reduce them.

It is a work where I try to restore complexity to people who have been portrayed as if they were objects, reduced to “types,” while filling the book with images of emotional connections and collages that engage with our diaspora. It is work that can only be done by going beyond the limits of active colonial institutional archives. From 2023 onwards, there will be two books with the same title “Journey to Brazil (1865 – 1866),” Agassiz’s and mine. If I ever manage to transform this artist book into a commercial book, I hope to place it in all libraries so that it can compete for space with the first. That’s how I understand the relationship between my work and the future.

Viagem ao Brasil (Journey to Brazil)

In most of your creations, you start with the image, especially the photographic image, but not only that. You also work with photoperformance, video, and photomontage. What is the place of photography and the image in your work? How do you perceive these languages, their different materialities, and their possible dialogues? What allows you to experiment, what is important as an artistic gesture?

Well, I have been reading, photographing, and making collages since childhood. Collage is a way of thinking. Everything that exists is a composition that breaks down and recomposes into different compositions. Life is metamorphosis and the production of differences. As an artistic tool, collage allows me to experience this tactilely, creating intimate connections with what I touch.

Photography is important to me as a visual inscription of the world into matter (physical or virtual). Like documents, they are textual inscriptions on a material. Collage allows me to break down these “finished” materials and recompose them in a way that expresses or communicates differently. Or if not that, at least making it possible to look at those materials in another way.

To do this, one must always keep in mind that each material has its own trajectory. A photo is a visual material. I have condensed the life trajectory of that paper, image, and referent. I consider the photos I take, whether they are photo performances, landscapes, or portraits, as elements that, like fragments, parts, will participate in the composition of collages, creating other figures.

For me, this is my artistic gesture: following the materials in their trajectories, interfering in their field of force to try to generate forms and figures along with them. It is a collaborative effort. What fascinates me about collage is the unpredictability of its result. For me, languages are tools. Each one enables a certain dimension of artistic production that can be extrapolated through compositions or collages between languages.

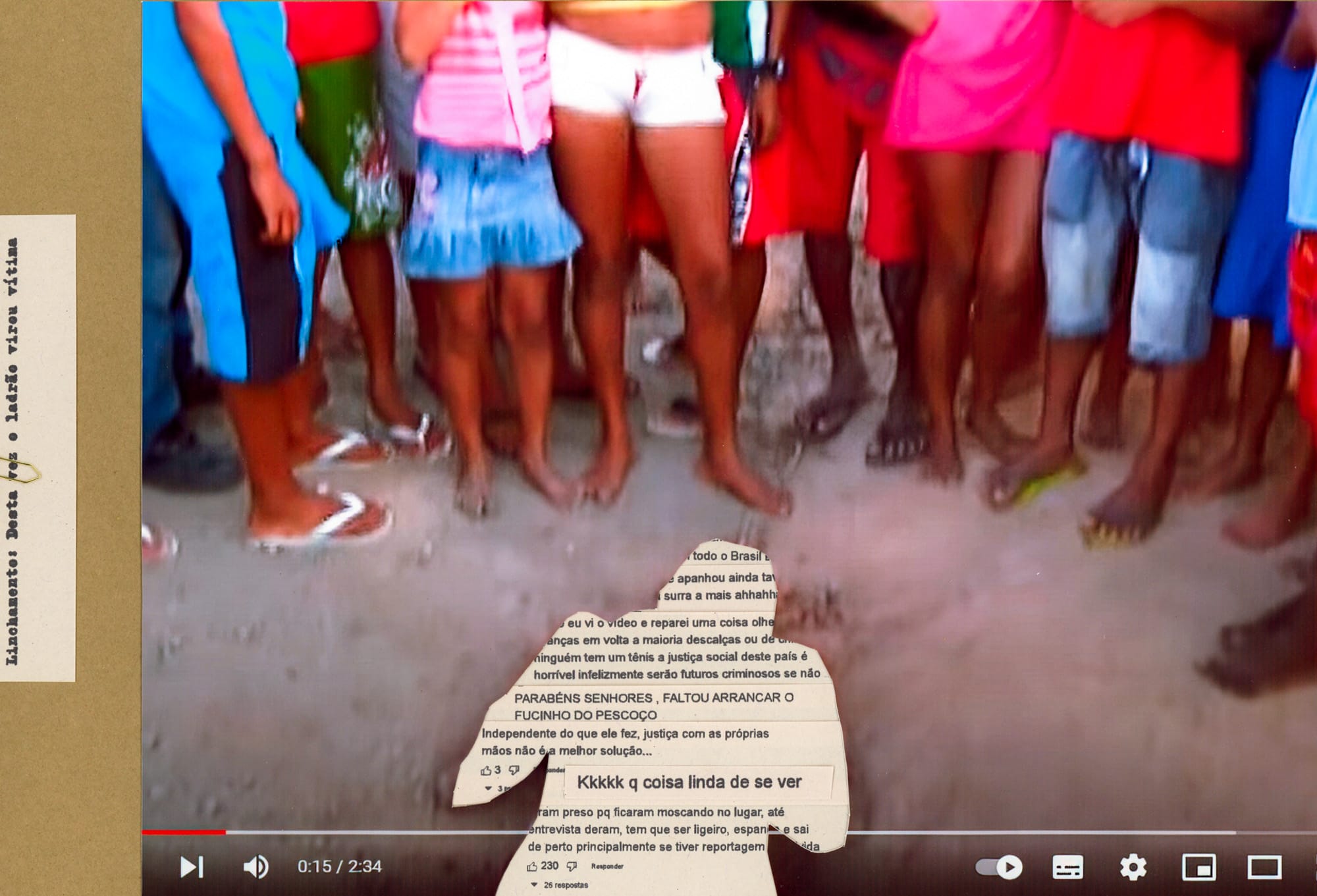

I can illustrate these issues a bit with “Transparency [2020 – 2023].” In this series, I start with images of lynchings, torture, and violence against blacks in Brazil and the United States from the 19th to the 21st century that are widely circulated on the Internet. These are moving archives, and what ensures the preservation of these virtual images is their circulation. What do I do? I copy and paste images and discourses that dialogue with scenes of violence. Most of them are available as comments, journalistic texts, on the site itself. In the case of Brazil, I am also interested in the penal legal discourse that authorizes or condemns these cases at the time.

I turn video frames, photos, paintings, drawings (all virtual images) into photos printed on photographic paper. I remove black bodies from scenes of suffering, a spectacle for many consumers. And in their place, I insert excerpts from the mentioned period’s discourses, printed on newspaper paper. Some of the violence images are for sale on the internet, and I also show the price at which they are sold on the website I took them from. The choice to work with photographic and newsprint materials is not random. There is a history of relationships (since the 19th century) between photography, the press, and the commercial spectacle of black suffering through these materials.

Several questions crossed my mind while working on this piece. I made it in response to the anger caused by the daily flood of these images and collective social anesthesia to their scenes. And I stopped the series when I realized that it is infinite because a new case can happen every day. The imminence of being a victim of extreme violence is the condition of life for blacks in Brazil. It is the hellish repetition to which we remain trapped.

Transparencia (Transparency)

Transparencia (Transparency)

In your work (understood here as the body of work), you are creating a new corpus of anti-colonial images. Sometimes by decolonizing archives, others by creating images that simply stem from other forms of knowledge, other epistemologies. What are those absent images that you cannot find and that provoke you to build a new collection?

I build this other collection of images simply so that from this moment on, there is another possibility of social existence for the archival images I work with. So that they can exist differently, linked to other discourses. Although we know that simultaneously they will continue to inhabit the archives under the aegis of violent colonial labels. I say this thinking mainly of “Journey to Brazil (1865 – 1866).” This is a case where the only images we have of the people portrayed are those made under Agassiz’s orders. By doing this, I make it clear to future generations that they can see the people portrayed as Agassiz saw them, as Harvard sees them, or they can see them differently, perhaps as I see them, as my ancestors see them. It is in this sense that I understand this collaborative work with these people portrayed, in a quest to create other possibilities for the future, to change the perspective.

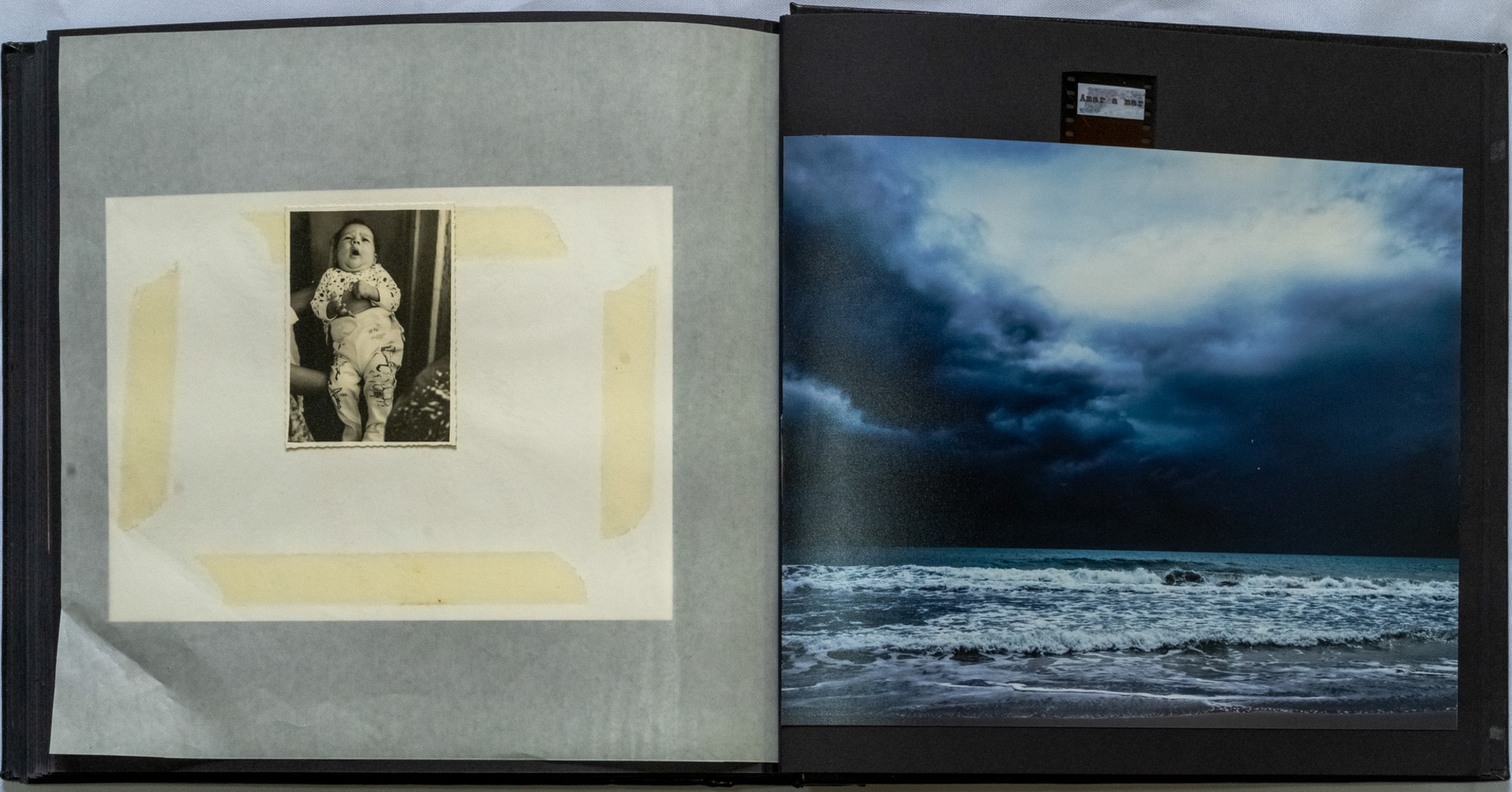

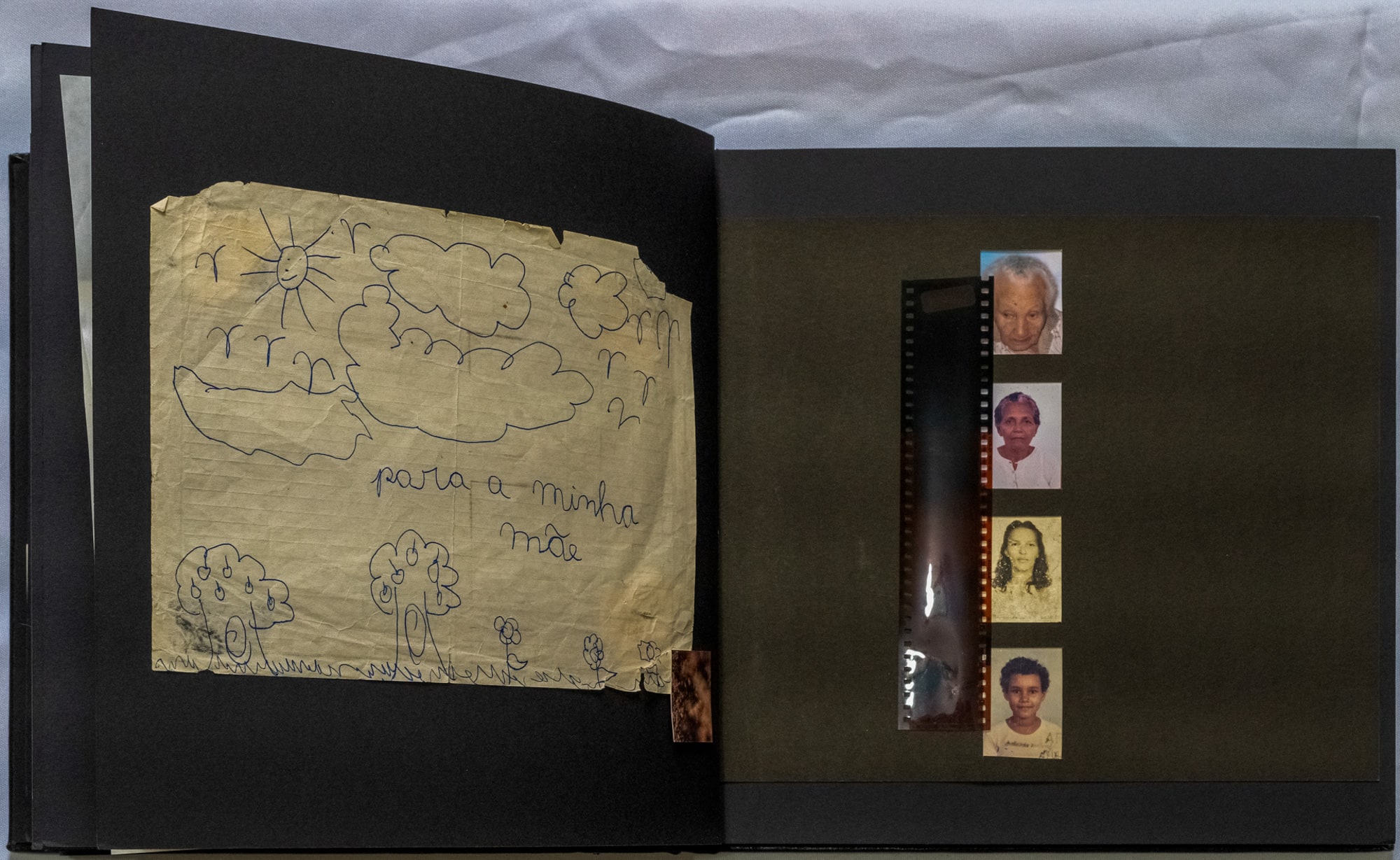

But when I think about my artist’s book “Minha Foto Preferida” [2016 – 2022], in which I narrate the story of my early years, I discover that many of the images we call absent are in the family albums of black and poor people in Brazil. In this book, I address, through documents and photos, topics such as paternal abandonment, colonial fictions, death, childhood, social struggles, state discipline and order, and love. It was crucial to discover through the photos how my mother and grandfather insisted on their loving connection, despite everything. I concluded this work understanding that much of what we consider absent in society, in the macropolitical sphere, can be found in the micro, in the warmth of homes, in communities of affection, trust, and exchange.

The media’s preference for making images of violence hyper-visible only speaks of the hegemonic colonial/capital political order. These scenes are normalized as something ordinary. Let’s imagine if we were flooded every day with images of happiness, joy, and satisfaction—what would happen?

Minha foto preferida (My favorite photo)

I believe that, to a greater or lesser extent, we always produce seeking to create dialogues with other people. For whom do you create? With which people are you interested in conversing based on these images?

I create out of vital necessity, to organize my feelings and thoughts, to release what dwells within me. It’s a process I consider healing, therapeutic, and spiritual. Having said that, I try to speak with anyone interested in the end of the world as we know it: the end of capitalism, colonial logics, white supremacy, misogyny—in essence, the end of all forms of domination necessary to sustain capital. I’m interested in speaking with both young and older individuals, from all social classes and invented racial classifications.

Will I succeed? Probably not, there are too many people fighting to defend their privileges on the brink of planetary destruction due to the climate crisis they have provoked. The colonial/capital world is a disconnected world from life, from the cosmos, and from the beings we have around us—it’s a world of death. So I do what I can with my body, with the space and time of this existence granted to me in this temporal form.

I hope that the images and texts I create are like seeds; whether they will bear fruit and what fruits will emerge from them, I do not know. Each viewer, each reader, decides what to do with what they receive, in their own time. But I hope they help create ruptures, to see other possibilities of relating to those who have preceded us, those who are here, and those who are yet to come. This is how I engage in the continuity of life.

Minha foto preferida (My favorite photo)