The Mobility of Images

Ricardo Miguel Hernández is a Cuban photographer and visual artist who works across photography, video art, installation, and film. Despite the versatility of image use in his practice, he maintains a strong preference for still images, especially contemporary collage, a central expressive resource in his artistic career. The act of montage, meaning the selection, cutting, mutilation of photographs, the juxtaposition of elements, the construction of meaning and metaphors, reveals the rebellion of images and the manipulative nature of photomontage representation. The freedom of creation, driven by the humor and irony typical of this language borrowed from European artistic avant-gardes like constructivism, cubism, Dadaism, and surrealism, which gave strength and notoriety to the technique in the 20th century, is very present in the artist’s work.

Por Maíra Gamarra

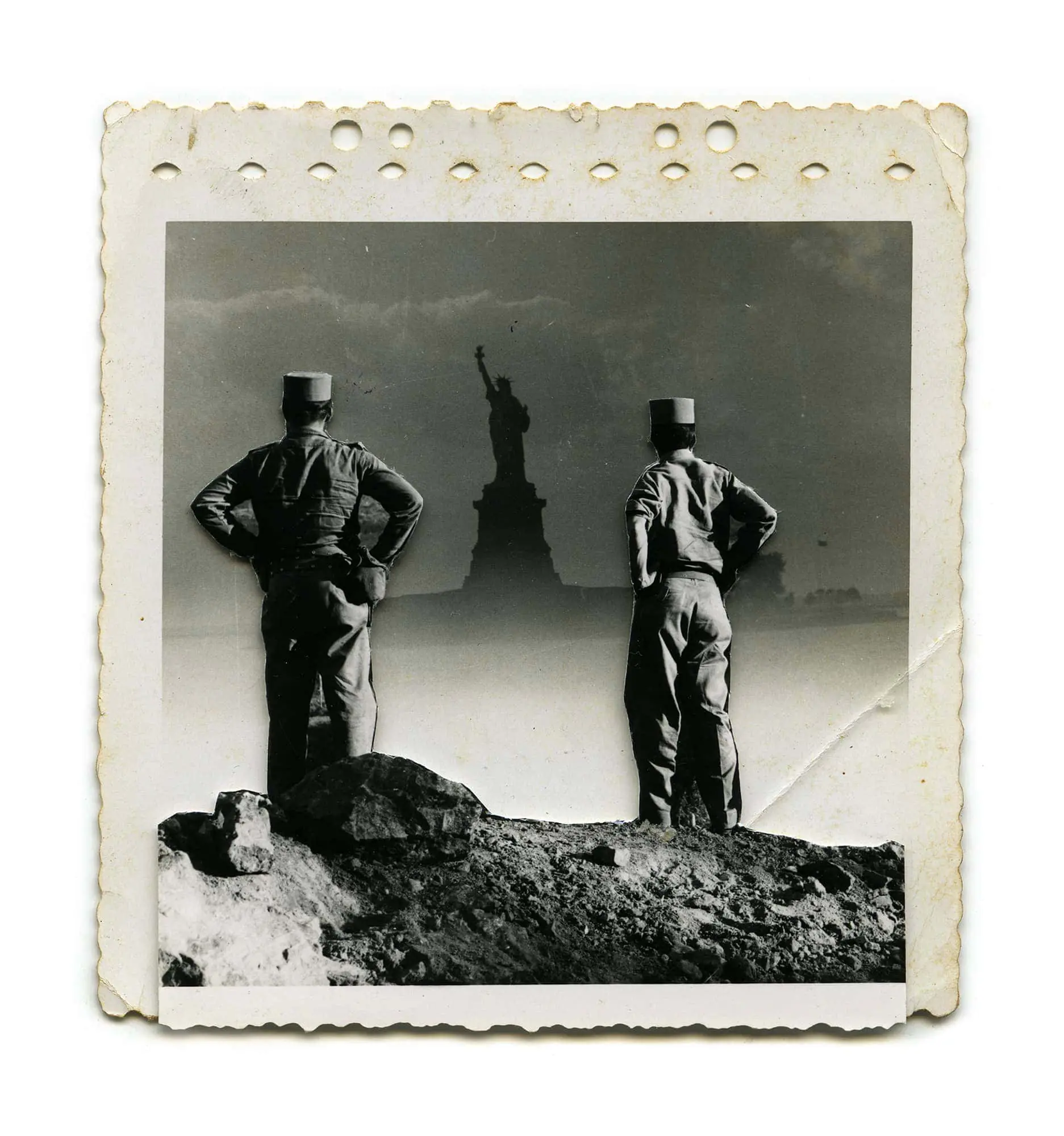

Forgotten photographs, often discarded, return to circulation through his work. Hernández rescues, collects, and archives images from bygone eras, which now follow different paths, creating new vocabularies and visual compositions that reconsider the history of Cuba and its people. Personal stories of illustrious unknowns, in contrast to major Cuban milestones, come back to life in the almost performative action undertaken in the construction of each piece that forms these meticulously crafted visual narratives.

Starting from photographic documents, the author expands the notion of the archive and its uses, broadens its significance, plays with the illusion of the truth of the image and its sanctity. In his work, deconstructing and reconstructing images, meanings, and memories become operations of systematic repetition, a constant exercise of reimagining that repositions not only fragments, pieces, and graphic elements but also traditional and hegemonic logics, representation codes, destabilizing their signs, and proposing new assemblages that sometimes reinforce their original meanings, other times subvert or counterpose them; in any case, the main function is the reordering of meanings through fragmentation, hybridization, and the restoration of power to the images.

Epiphany (Epifanía)

Your work is focused on the ambiguity of historical, political, social, and familial memory, which you use for the reconstruction of memories and the remembrance of Cuban history. What do you aim to discuss with your images?

The history of Cuba, as I see it, goes beyond the known and legitimately established historical narratives; it is a history filled with contradictions, fictions, and hidden facts, always open to be filled with new narratives: both true stories and, in many cases, fictional ones.

As Alfons Cervera said, “History is built on the inescapable basis of the truth of the events it recounts. But sometimes history is also built with the additions of memory. And memory, as we also know, is the sum of the accuracy and inaccuracy of memories.” It is in the inaccuracy of memory where I am interested in constructing new narratives.

Memory is a container for memories, more or less organized, that we store there and forget or keep according to our priorities and desires. In my work, I operate within the flexibility between history and memory; in that oscillation between a real, verifiable event, a family memory, or a social scene, and the new historical construction that I give to that rescued memory. I try to create an atmosphere where reality and fiction complement each other, rather than clash. It’s like a poetic of wandering.

Land!

How do you choose the images to work with?

I have a large photographic archive that I have been building for years. This allows me to have numerous options to choose the images I want to work with. Many times, I have a small sketch of the work I want to create and the type of image I want to manipulate. It’s a matter of finding a photograph that comes as close as possible to what I have in mind. Other times, I simply look at photographs repeatedly until an idea emerges. A photo can be stored for a long time, and each time I see it, something may appear that I hadn’t noticed before. That “something” can lead me to create a piece. Other times, the photographs are there, waiting for other photos to appear and complement them.

I acquire the photos through purchases at antique markets, from families who sell them to me, from friends who give them to me, and even from photos I find discarded in the street or in the trash. They are all interesting, whether they are broken or dirty.

Untitled

Collage is a subversive art that questions the notions of representation, originality, ownership, property, and authorship in photography, which is why it still seems to carry the stigma of being a lesser art, as it uses images created by some and appropriated by others in different contexts from those in which they were created. Do you think the perception of this technique has gained new dimensions?

Collage, without a doubt, is the most authentic manifestation of the 20th century and has influenced other forms of expression such as film, television, literature, advertising, and music. The notion of collage is that important. In visual arts, it had its heyday in the early 20th century with the avant-garde movements. It has been present in the works of great visual artists throughout history. Collage itself does not require technical rigor or craftsmanship as painting, sculpture, engraving, and even photography do. Painting requires knowledge of drawing, mastery of color palettes, and composition, among other things. Making a collage doesn’t require a specific craft; you simply need to learn to cut, perhaps. Because it is a technique that can be easily accessed, there are countless collages lacking energy, content, and emotion. They are meaningless and excessive superimpositions that lead nowhere. Finding true collage works is a great challenge. Nevertheless, you can find excellent works by contemporary artists with sharp perspectives; works with a strong political content, like those of Martha Rosler and Alfred Tarazi, or collages that discourse on identity, gender, race, and decoloniality, like those by Chelle Barbour, Frida Orupabo, and Giana De Dier. Even in the music industry, the cover designed by artist Fred Hidalgo for the seventh album “Recipe for Hate” (1993) by the punk rock band Bad Religion and the cover of the album “Insomniac” (1995) by the punk rock band Green Day, designed by artist Winston Smith, are true visual gems.

Untitled

Over time, you have created different series that touch on various themes and moments of your artistic research and experimentation. Can you tell us a bit about these processes? Which series do you find most representative of your work?

The backbone of my work is undoubtedly photography. It is present in both analog and digital photo collage series, in my videos, and, in recent years, in my physical collages. In these analog photomontage series, “When Memory Turns to Dust” and “This is Not a Love Story,” I began working with the materiality of photographic paper, cutting, tearing, composing, juxtaposing.

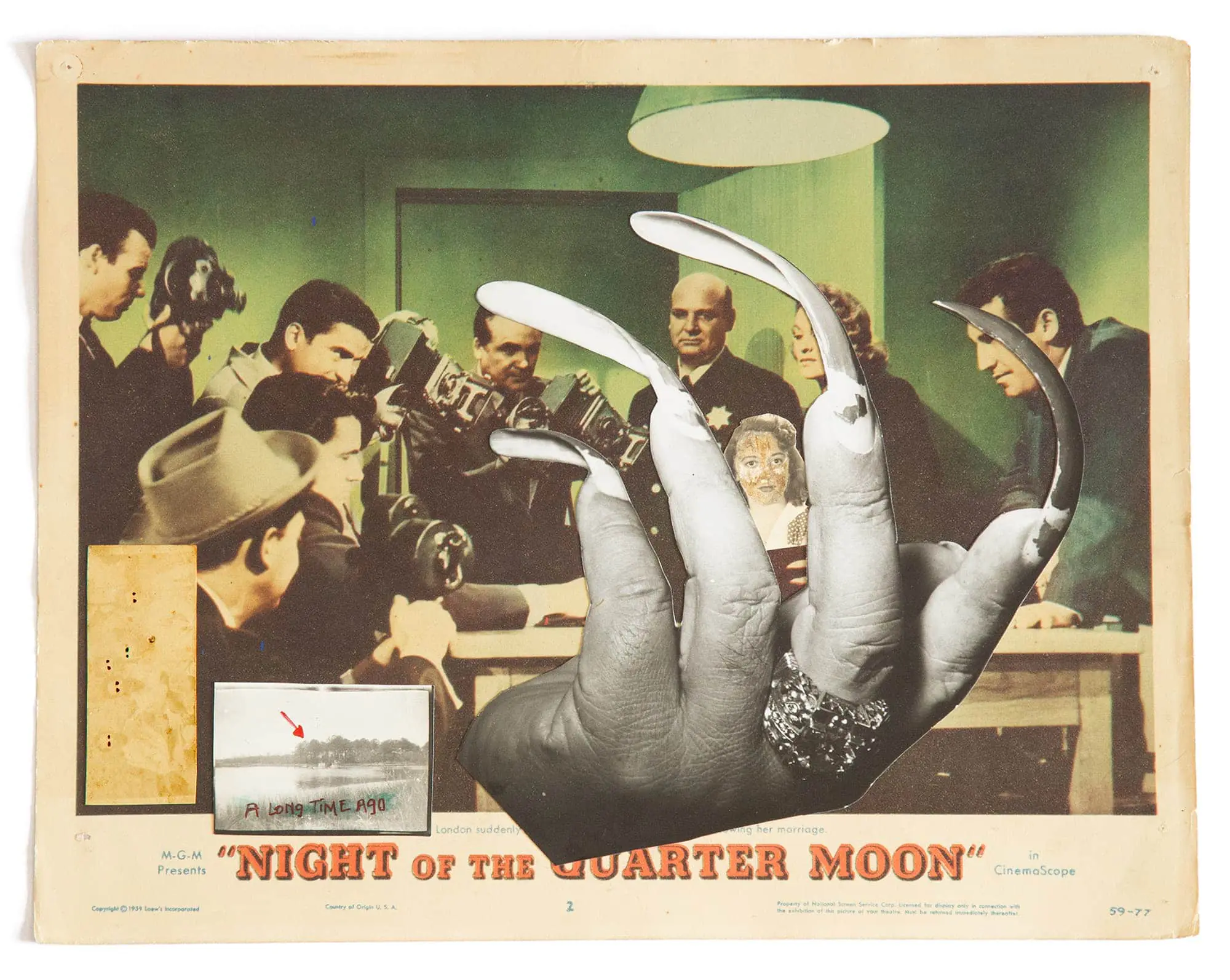

“This is Not a Love Story” (2018-2023) focuses on the history and memory of the Cuban subject by valuing the photographic archive. In this work, I’m only interested in working with Lobbycards – small movie posters that were placed on cinema marquees to announce film showtimes – and photos from the 1940s to the 1960s. I combine photographic portraits of anonymous or non-anonymous figures, polaroids of travelers, family environments, and social scenes with the scenes reproduced in these Lobbycards corresponding to the genres of melodrama, westerns, and thrillers.

Series: “This is Not a Love Story.”

In “When Memory Turns to Dust” (2018-2023), I aimed to push the boundaries of photographic artistic practice to assume a transdisciplinary and hybrid approach directed towards the rescue, reformulation, expansion, and resemantization of found archives. I conceive the image as an evolving idea. For this, I start with an interest in everything that exceeds the limits of photography as a technique and concept: from how it is displayed, perceived, and consumed. I appropriate a residual, dusty archival testimony, classify it, and manipulate it consciously, expand its conceptual matrix, and meticulously craft new artistic metaphors, juxtaposed, assembled, mutilated: without trying to conceal the residual marks of time.

De pronto se escuchó la voz (All of a sudden, a voice was heard)

Mariconá con el caimán dormido (Mariconá con el caimán dormido)

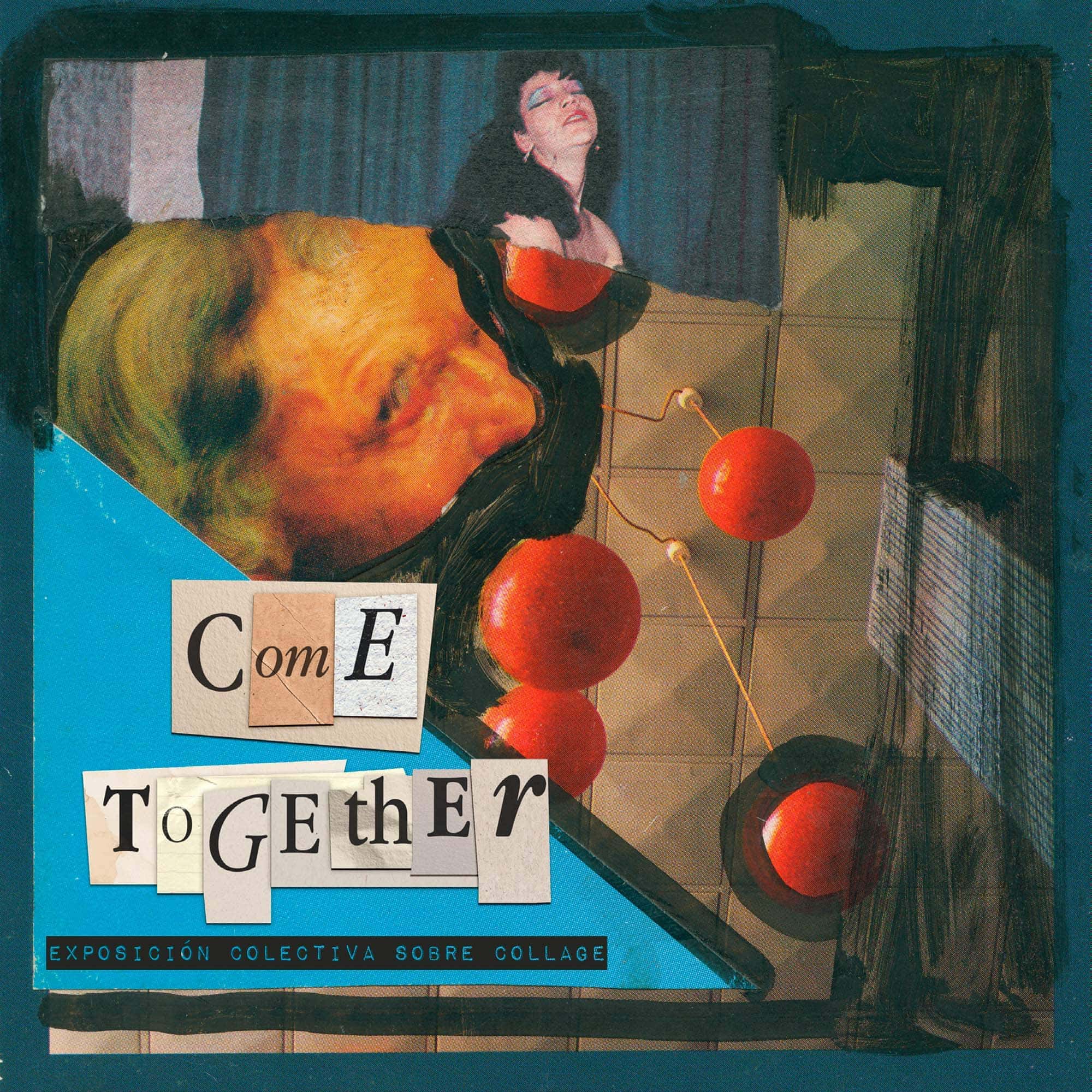

At this moment, you are appearing alongside Yenny Hernández as the curator of the exhibition “Come Together,” a collective exhibition on collage that combines works in photography, video, performance, photomontage, digital collage, and installation, which is on display in Havana. Tell us more about the exhibition, the collectively undertaken curation, and the discourse you are presenting.

Working hand in hand with Yenny Hernández on this curatorial project has been a challenge and a growth experience for me. It has been an enriching experience in the sense that this is my first critical approach and full commitment to curating. Doing it with the guidance and assistance of Yenny, an unparalleled Cuban curator and art critic, has been a total gain.

This exhibition serves as the first step within a larger project that we have been working on consistently for some years, focusing on collage practice in Cuba. As a result of the research and investigation we have been conducting, we organized an initial exhibition where our curatorial idea was to showcase how collage has been adopted and interpreted by Cuban artists of different generations and disciplines while stimulating interest in the Cuban art and critical scene regarding collage. Collage has been and continues to be a practice overshadowed and considered minor within the art history of our country.

Cover of the “Come Together” exhibition catalog.

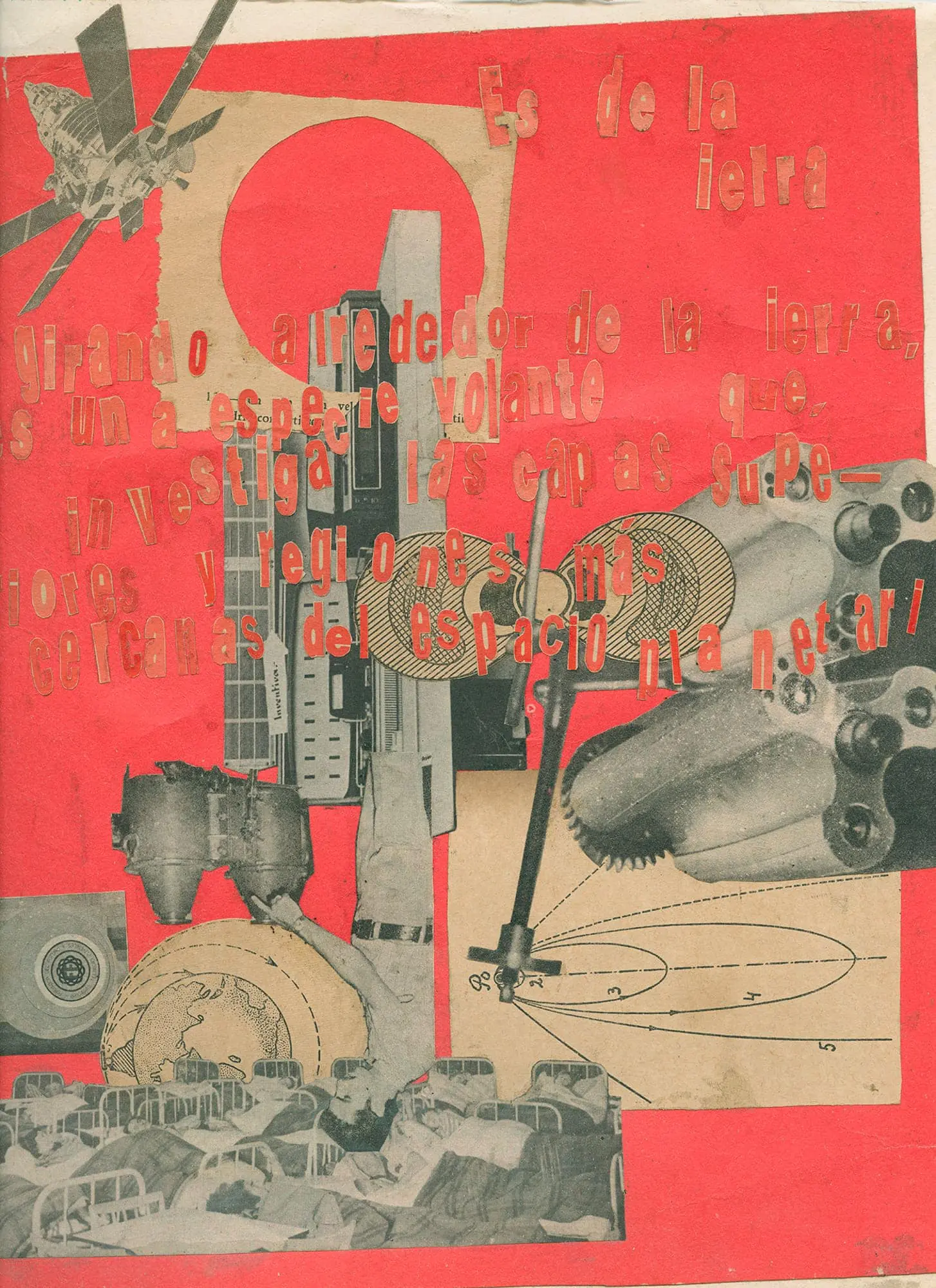

The selection criteria for artists and works led us to articulate a showcase of different generations, art forms, and professions. We emphasized the latter because we were very interested in the literary component in relation to collage. We realized that it was a constant resource for several artists to critically round out or compose their work. We invited writers to be part of our curation, and they had impressive and notably exquisite collage works, most of which were unpublished and unknown in our country. Additionally, our intention was to create an exhibition that could be understood at its core as a kind of mega-collage. We aimed to exhibit a diverse range of media and aesthetic languages that reaffirmed the idea of collage from a creative perspective. In “Come Together,” you can find works created using traditional collage practices as well as others that adopt more contemporary languages, including photomontage, assemblage, video collage, and digital collage.

Artist: Nelson Barreda

How is the reception of collage art in Cuba?

From my experience as a Cuban artist who has been immersed in the complex and intriguing world of collage for several years, I can tell you a bit about its reception in Cuba, which is virtually non-existent and lacks theoretical support or academic studies. “Come Together” is an exhibition that has allowed us to take the first step in reevaluating and showcasing valuable names and aesthetics within Cuban art in terms of collage practice and discourse, due to the absence of studies, exhibitions, publishing projects, or specialized texts in our country on the subject. We have identified a long list of artists who have at some point in their careers engaged in collage, but these works have remained in the shadows. This is not solely due to a lack of aesthetic and critical strength in the pieces but often because collage has not been given the recognition it deserves. In Cuba, many artists have worked with and explored collage, but these lines of creation within their careers are unknown. This is one reason we believe that “Come Together” awakened dormant interests and ignited lights not only in artists but also in critics and curators. For us, that’s one of our most significant achievements—to have managed to develop an exhibition that made a mark in the Cuban art scene.