“We are more than a virus”

A conversation with Diego Argote about his work “Yo, Fulminada”.

By María Rivas

In the peripheral corners of Santiago, Chile, the exploration of Diego Argote, a seropositive photographer and visual artist, takes root. In his works, he sets a starting point for critical, political, memorial, and affective contemplation, both of biographies and autobiography.

His creative process encompasses photography, sculpture, installation, and video with the aim of exploring approaches and discrepancies with otherness.

According to them, their essence is woven into the textures of their childhood, amid the scents of paints and the mysterious charms of shoeboxes filled with visual memories of their family.

In an intimate conversation, Diego shares with us their early visual references rooted in the houses of their aunts and grandmother, places where art manifested itself in every space, from brushes to captivating photographs.

The love for photography intertwines with the memories of their grandmother, a narrative that delves into the magic of photographic rolls, the quest for the perfect light, and precise instructions to capture irreplaceable moments. In this environment, Diego discovers the spark that ignites their desire to become an artist, a flame that continues to burn today, guiding them through turbulent times following a positive HIV diagnosis.

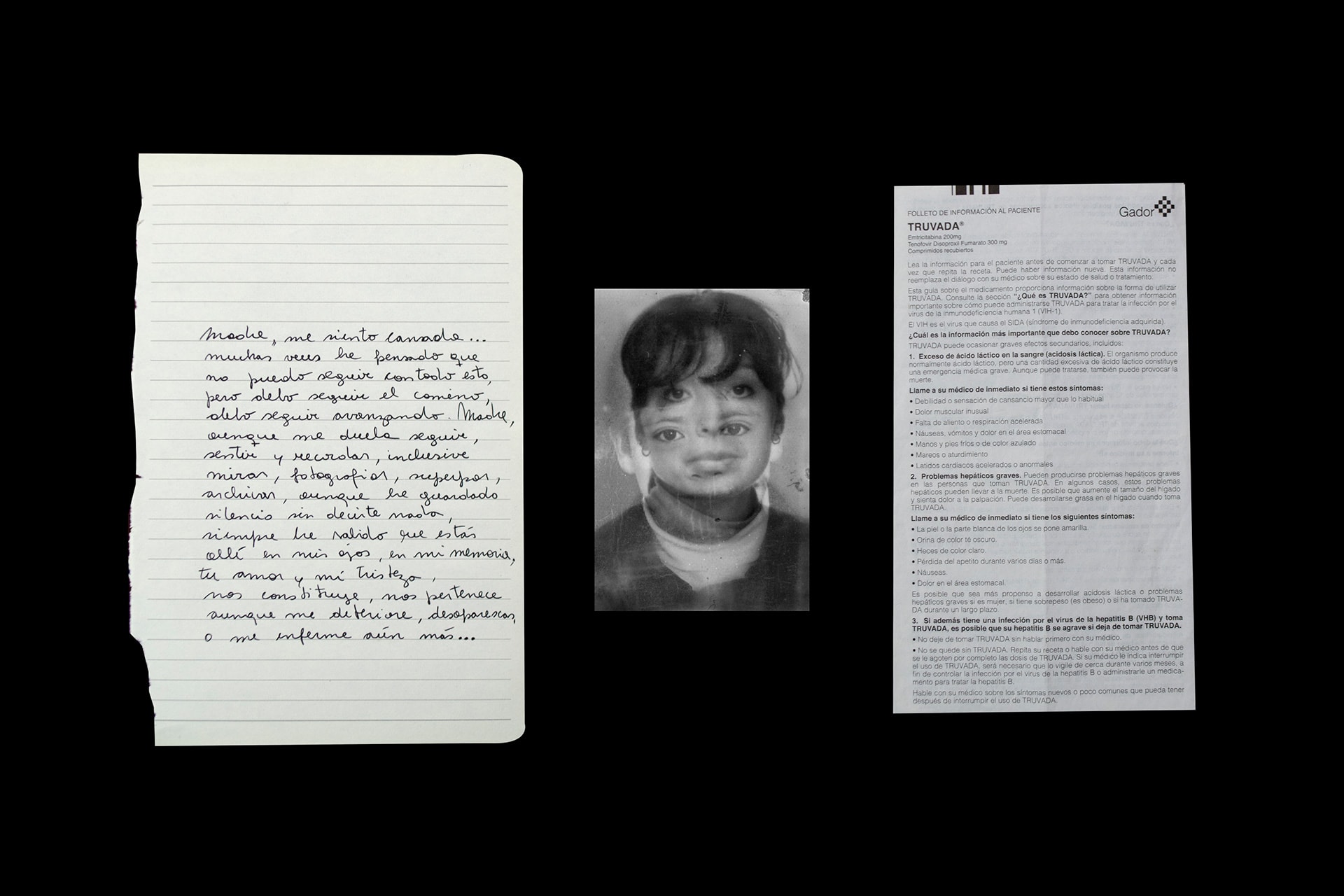

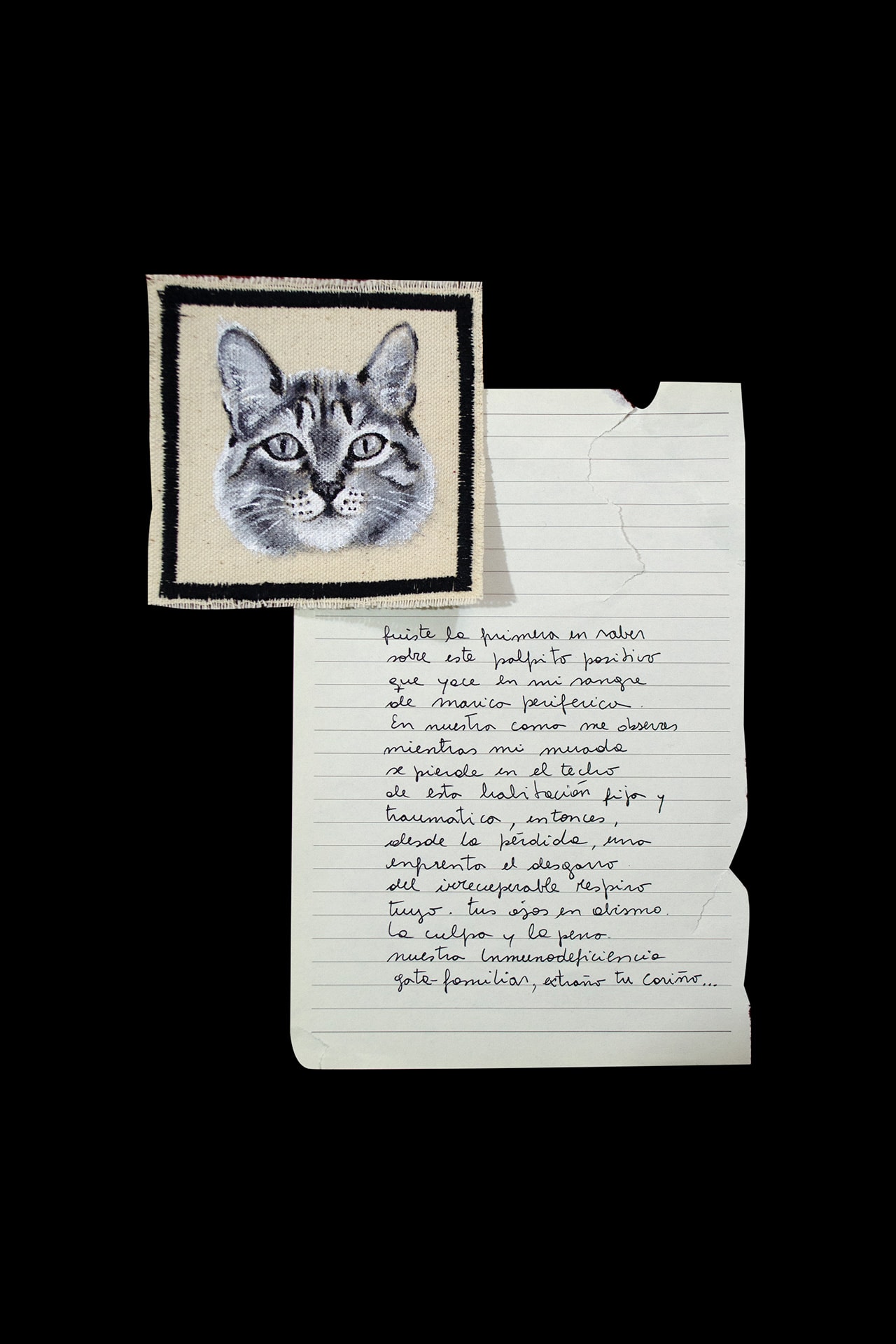

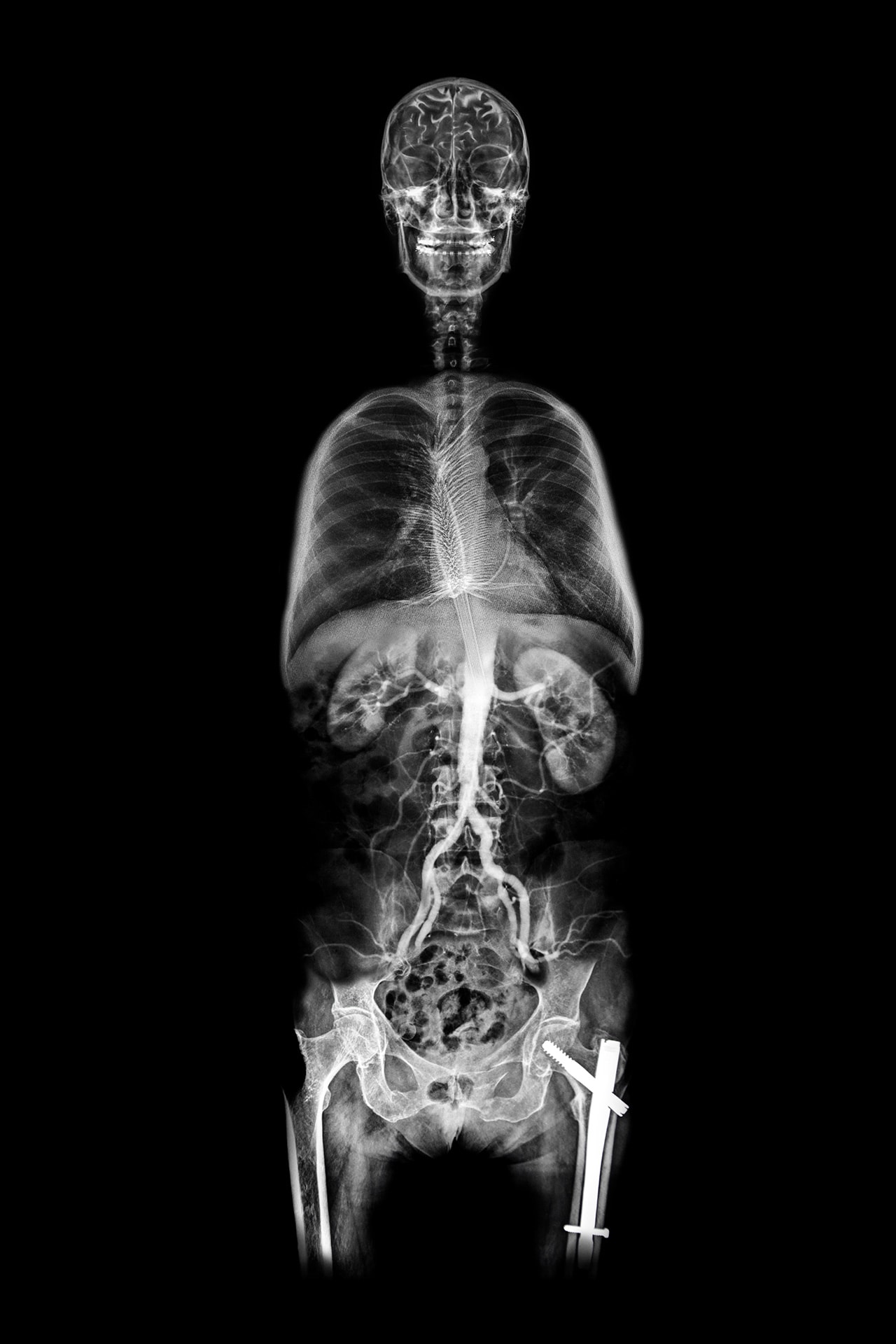

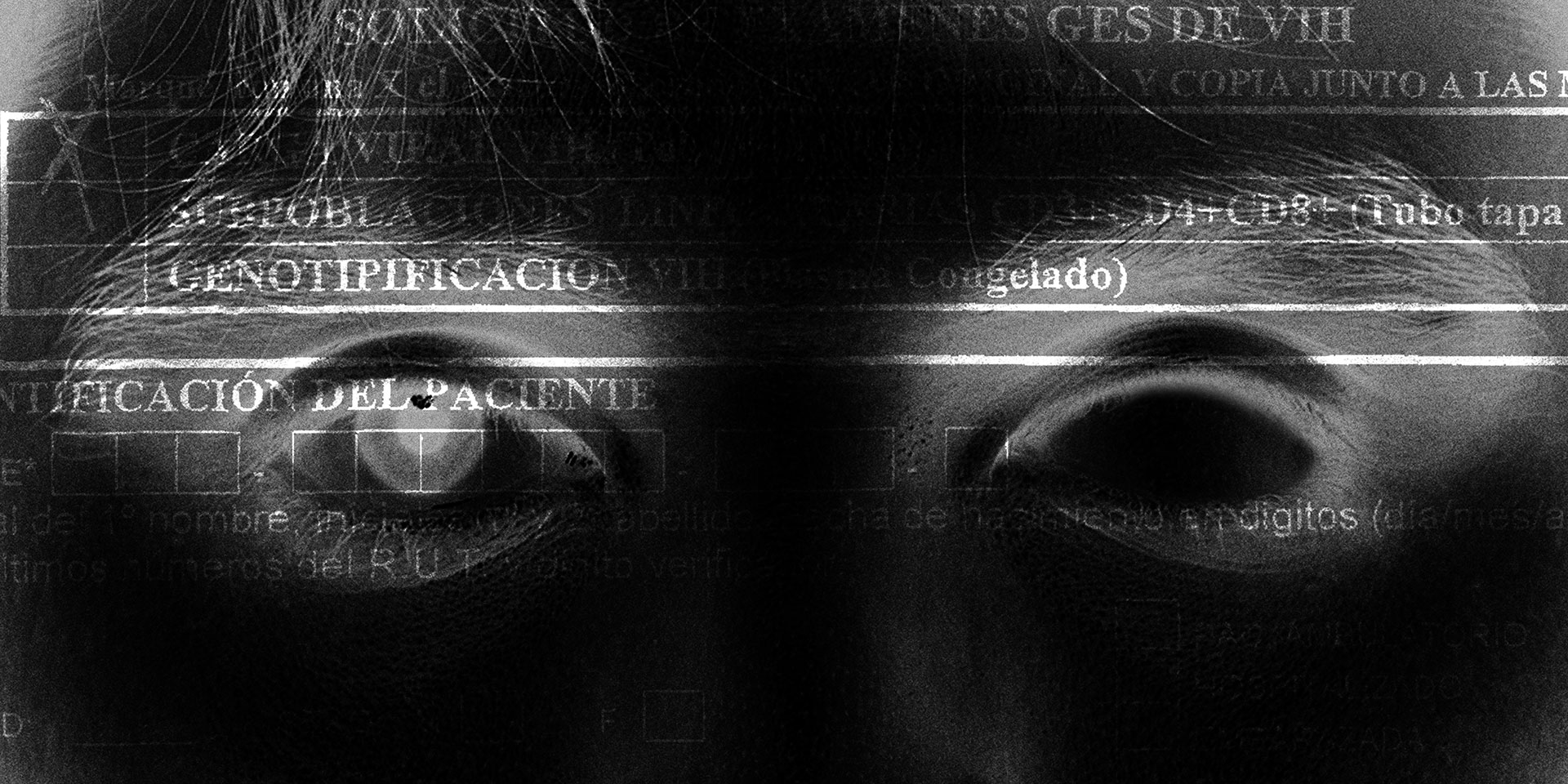

“Yo, Fulminada”, courtesy of Diego Argote

However, Argote’s influence is not limited to their family environment. In the vibrant queer artistic panorama of Chile, they find inspiration in figures like Victor Hugo Robles (“the Che of the gays,” as they describe him), Carlos Leppe, Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis, Gabriela Mistral, and contemporaries like Seba Calfuqueo. For Diego, friendship and sisterhood intertwine, learning and inspiring through close connections with people like Juvenal Barría, Iván Monalisa Ojeda, Guillermo Moscoso, and many others who shape their creative universe.

Their works, filled with political, gender, and aesthetic elements, resist linearity, challenging established norms and homonorms.

As we explore Diego Argote’s artistic world, we embark on a journey beyond conventional forms, embracing the complexity of identity and challenging imposed limitations. In each display of their work, Diego invites us to question, feel, and celebrate the diversity that pulses at the heart of their creative processes.

Here is what they shared with us:

Tell me a bit about yourself. Why did you decide to become an artist? How was your first encounter with photography and art?

I am Diego Argote, living in Pudahuel, a peripheral commune of Santiago, Chile. I have always inhabited the arts since childhood, in the homes of my aunts and my grandmother. My grandmother always had drawings, cutouts, and photographs in her house and in shoeboxes that fascinated me every time I visited her. They were incredible objects full of curious things that she created. In my aunts’ house, the smell of paint fascinated me. The various brushes and those canvas-covered wooden frames enveloped me with excitement, and I think in those two places where I lived as a child, the need or the idea of copying what they did emerged.

With my grandmother, I opened up more to experimenting, discovering, and exploring. I wanted to be an artist like her.

The encounter with photography was also as I mentioned, in my childhood. Sometimes it sounds like a cliché when one talks about it, but the truth is that’s how everything happened. The photographs in the shoeboxes of my grandmother, seeing my grandmother buying photographic rolls for her small black camera, accompanying her to pick up the photos, seeing how she photographed, hearing her say, “move here, further back, forward, look at me, there is the light.” It always captivates me when I think about it; my grandmother, so in love with images, transmitted that passion to me. It was there that I decided to be an artist; it is something that still stirs me today, and I think without this, I could not advance in these turbulent times.

“Yo, Fulminada”, courtesy of Diego Argote

In many of your works, political, gender, and aesthetic elements can be seen. How would you define your art?

It’s difficult to answer and define this. My work is not linear, nor is it heterosexual. It is disobedient, battling against violence and even homonorms. Sometimes, my friends and I think about a collective definition that becomes particular at the same time: feeling “baroque,” meaning pessimistic, dramatic, expressive, pathetic, suffering, irregular, vomitive, unequal, monstrous, crazy, very crazy.

Do you think art is also a form of “catharsis” to express emotions or political stances? How so?

When I work, I don’t seek healing, nor do I pretend peace. I think the arts have helped me cope with the systematic blows I have experienced since childhood and that still haunt my interior. Likewise, it gives me strength and confidence to face these current wounds as a young adult. People often mock sadness or criticize it gratuitously, reproach with punishments. But the truth is, no one should make fun of this. Grief is political, and from there, I affirm, reaffirm, inscribe, construct, and protest against all violence.

You are a photographer, but in your works, you use other media like video or sculpture. Your works belong to different platforms and become a kind of artistic hybrids. Why use more than one medium to convey something?

I have always thought and resonated with the word “unmark,” step out of the frame, distance oneself. And that’s what I do, step out of the photographic frame, cross its framed impression that is installed on a commonly white surface, a wall. I seek another visual corporeality, other desires, another voice, other sounds, leaving verticality and horizontality to become oblique. I prefer to disobey the static and aesthetic norms that photography generally designates or imposes. I love photography, but it is not my only means to dialogue with otherness; I prefer to experiment, using my corporeality in conjunction with other materialities in zones of enunciation, sadness, and denunciation. They mobilize me.

Now, let’s talk about “Yo, Fulminada.” You describe yourself in several interviews beforehand as a seropositive artist, and this work delves into this topic. How did you want to approach this work that can even be autobiographical?

When I talk about being a seropositive artist, it is placing myself with strength and resistance in the world I inhabit; thanks to the political, queer-trans-lesbian-dissident voice of all the comrades who have historically fought in societies. I was born in a country called Chile, a punishing territory, with fear and without memory, and I don’t want to be afraid, or feel punishment, let alone guilt. I get up without fear, shout without fear, show myself seropositively without fear, I have memory, with my loves (friends), we have memory.

Naming myself seropositive is to make visible what is still a problem for many people; the hatred towards diverse bodies persists, even more so if we are openly walking viruses. I empower myself with this and mention it openly. At the same time, I allow myself and invite everyone, within their own decisions, to live seropositively openly, without apprehension. These are complex times, and we need to continue fighting collectively and individually. The hate of some people trying to make our bodies and memories disappear cannot torment us, stifle us, or destroy us; we are more. I don’t place myself in silence.

“Yo, Fulminada”, courtesy of Diego Argote

And that’s why “Yo, Fulminada” was born. Something fulminating is something that has been destroyed/shattered/hurt, like a shot at someone or a lightning bolt that quickly breaks a tree. When I say I don’t place myself in silence, it is precisely not to remain silent, and this is precisely due to a complex moment I experienced, a medical violence that I had to endure in the medical room because, also, one is vulnerable, and that day of exams, I wasn’t emotionally well.

That a homosexual doctor from a foundation tells you gratuitously: “you will die of a cardiovascular brain infarction because you’re fat and positive,” that verbal spit in my face unleashes in me frustration and rage, and also a sharp pain that weakens my identity. That day I escaped, ended up in the emergency room because a part of my chest had swollen, and I couldn’t breathe, along with a brutal headache that invaded me because I had a lumbar puncture, as they needed to rule out any problems in the cerebrospinal fluid. And as justice never exists, I stirred everything up in the best way. Rebelling against violence was visually working on this pain and autobiographically which, at the same time, became biographical because it made sense to other people’s violence that observed this work or even dialogues I had with close people and hospital patients.

How did you decide to express that process in your work?

In this work, I worked with X-rays of dead bodies and two particular radiographic files of the face and chest, plus other plates of bodies that were part of this process, along with superimposed looks with serological files of evaluation and requests for exams. To this, I added a drawing of my first feline daughter, to whom I first spoke about my processes of living with HIV through a letter, plus, a letter to my mother with a photo of us (me as a child and she as a young woman), talking a bit about how difficult it has been to discuss this topic with her, and finally, a letter with a photo weathered by time.

“Yo, Fulminada”, courtesy of Diego Argote

I finished and complemented it with a video in which I talk (voice and text) about medical violence and the importance of strength and love towards loves (friends) as processes of listening, resistance, and struggle represented in a historical scene in Chile, like the Candlelight March of Santiago, Chile, in May 1996, which has been important and attended under a scenario of political and street struggle.

It has been an intense, intimate, and collective process to address this issue, which still, in these contemporary times, remains a subject of rejection and fear, highlighting the need to work more forcefully against the absence of public health policies and for the much-needed sexual education, which we could have obtained and worked on not long ago if it hadn’t been for the disastrous decision to vote against a new Chilean constitution. There we could have grown… Chile, a mean and cynical country.

But well, this work has allowed me to continue living and fighting with HIV/AIDS in the world, never alone, and it is one of the many earthquakes that have brought me closer to other people to engage in deep, urgent, and necessary dialogues to keep moving forward.

Tell me more about this. In the speech that comes out in your video for “Yo, Fulminada,” you talk about your country and the people who are seropositive there. How do you think the perception of these people is in your country? Has the stereotype from the ’80s and ’90s transformed to today? How to combat those perceptions?

Chile is complex, especially in these times. I’m not sure what to think about the decisions or reflections that the people have taken for their future today. Recently, we were in a significant, disobedient, politically marvelous social upheaval. In the streets, we, the seropositives, demanded more rights and less sero-hating violence, just like many other important demands from an angry people. But what happened? Everything came to nothing; all purpose dissolved. Complaints from horrific politicians began, people without memory, terror campaigns, lies galore, and as always, television doing its thing: blind, deceive, numb.

People believed it. They voted against, violating the desires of many people, of us, leaving a historically brutal wound. There was an opportunity, and it disappeared. What hurts the most is seeing how the people without memory forgot about the mutilated, humiliated, murdered people.

Some of these people committed suicide.

Chile became selfish, and today, they only talk about fear and yearnings for soldiers in the streets. This overwhelms me. Latin America is upside down. We are breathing an abysmal regression, and people still label seropositive individuals as disgusting, immoral, sinful, etc.

Not long ago, some evangelicals on the street were talking about AIDS, saying that God punishes the AIDS-infected for being sinners, heretics, for not believing in the family, for not procreating, etc. Evangelicals today in these times, can you believe it? Or a young driver who responded to his radio while listening to a political debate on some random podcast while I sat silently in the back. The debate was about sexual rights and feminisms, HIV-positive women. The young man said they brought it upon themselves because they were dirty and feminazis and that they get infected because they are immoral idiots. The term “infection” is horrible, it shouldn’t be used; rather, “transmission” should be used, but well, the context was horrible. I tried to refute, protest, but the character got dense. I avoided violence, got off angrily.

In other words, these contemporary times are tense, and I think we are inhabiting a thick and dangerous fog. I wasn’t born in the ’80s but in the ’90s, and I think violence still resides, and they still think HIV is AIDS and that it is synonymous with death.

Today, there are medicines that prolong our lives, and it is necessary to urgently teach the differences between HIV and AIDS, but what about aggression, discrimination? Or the countries where being dissident and seropositive is punished by death. I also think about the lack of medication. I’m not sure where we are headed, but those of us who envision ourselves with pride in our way of being and becoming must continue fighting. No one has the right to overshadow us and silence our existence, and as I once read in a beautiful and peripheral bathroom in Santiago: we are more than a virus.

Using the “I” in your works is also something recurrent. Do you think art is also a form of self-exploration? In what way?

The arts themselves are explorations, investigations, learning processes, dialogues, discrepancies, diverse explosions, etc. When I think of this “self,” I don’t approach it as something particular but rather contemplate or reflect on its multiplicity since it’s not just my pain or complaint. It’s an arena where many individuals who witness these processes and results position themselves or become part of it.

“Yo, Fulminada”, courtesy of Diego Argote

At this point is where necessary encounters of listening and conversation blossom, and desires, aspirations, and teaching methodologies can be established, as well as strategies for confrontation when it’s necessary against systems of repression, neglect, and contempt.

“I, Struck Down” is connected to another of your works: “I, Hybrid.” How are they related?

Understanding this “self” is not singular but rather “selves” in the plural. “I, Hybrid” arises from childhood pains, violence at school, a strict father, the discovery and desire not to be identified as a man or a woman, to be other.

From there, the concept of weeds emerges as resistance and insistence. Weeds are always rejected; they are cut, thrown away, or burned. But they always reappear; they are disobedient and stubborn, resisting, and that’s how I have felt from childhood until today.

I hid behind these weeds as a refuge, becoming one and understanding others. It is a photographic, written, and video work. Here, the weeds take center stage, and in a culminating and initial moment, the viral transmission to the organism arises and is reflected in a radiographic photograph where my lungs overlap with a weed, a thistle as an incision intertwining with “I, Struck Down” as an act of denunciation.

In other words, both works intersect as visual, reflective, political, and emotional bridges in critical moments of a collective autobiography.