When his father was killed, Andrés Cardona was three and a half years old. His mother took him to the military headquarters to claim the body. When she was killed, Andrés had already turned four. Where she is buried is still a mystery.

Andrés is part of a lineage of peasants. His family comes from Tolima and since the 1950s, about twenty of its members have been murdered. “Not only those closest to me, like my dad, my mom, uncles, cousins, also my great-grandfather, and other women were beheaded,” he says.

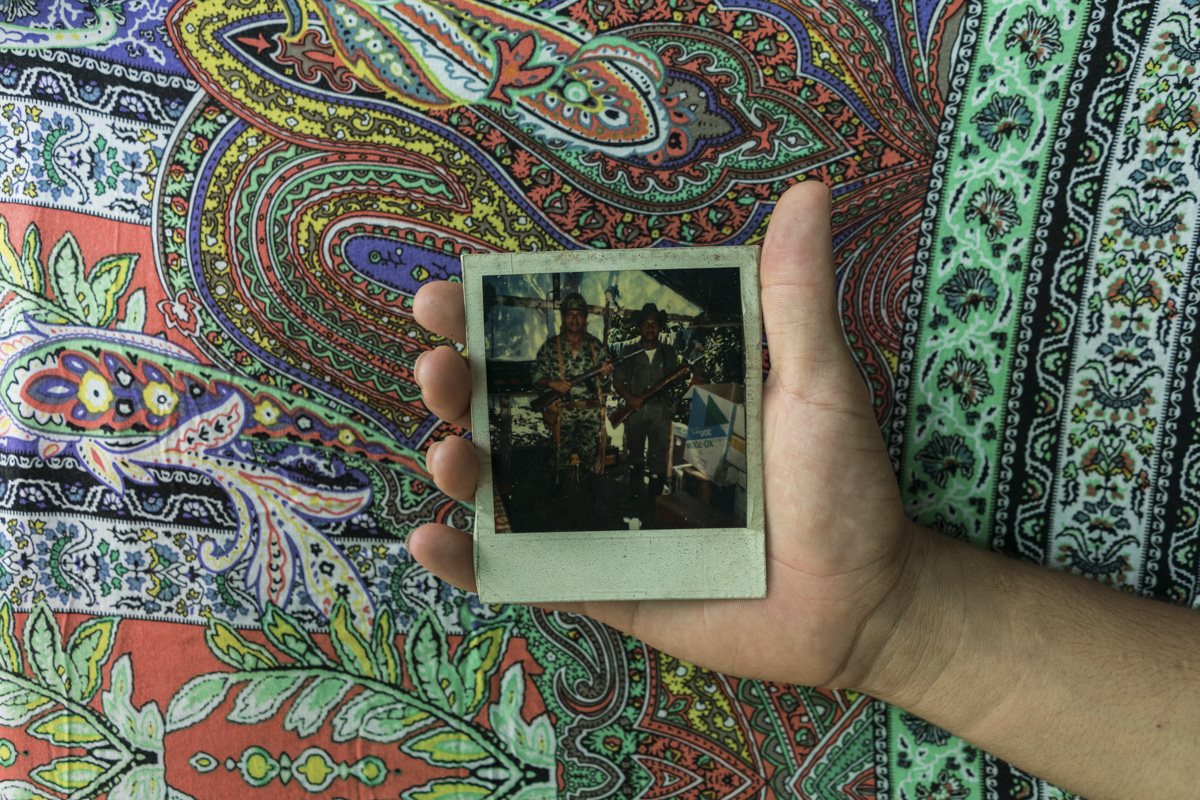

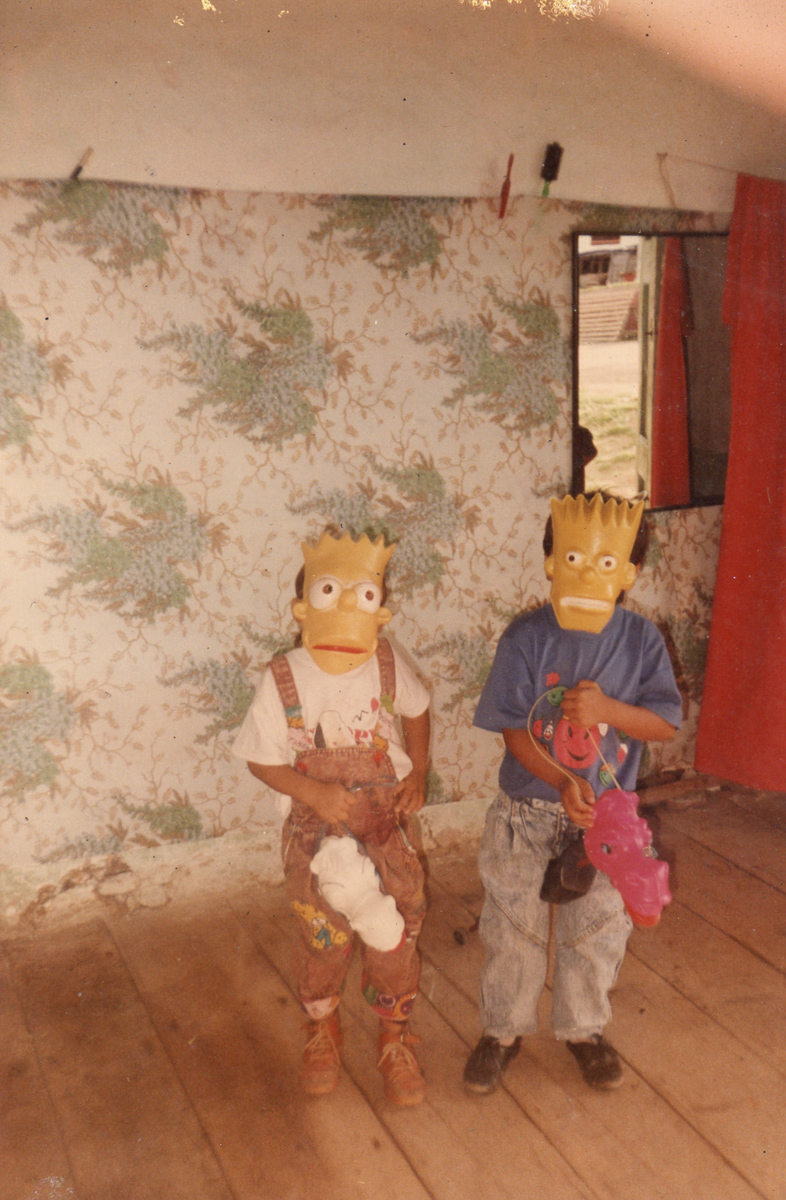

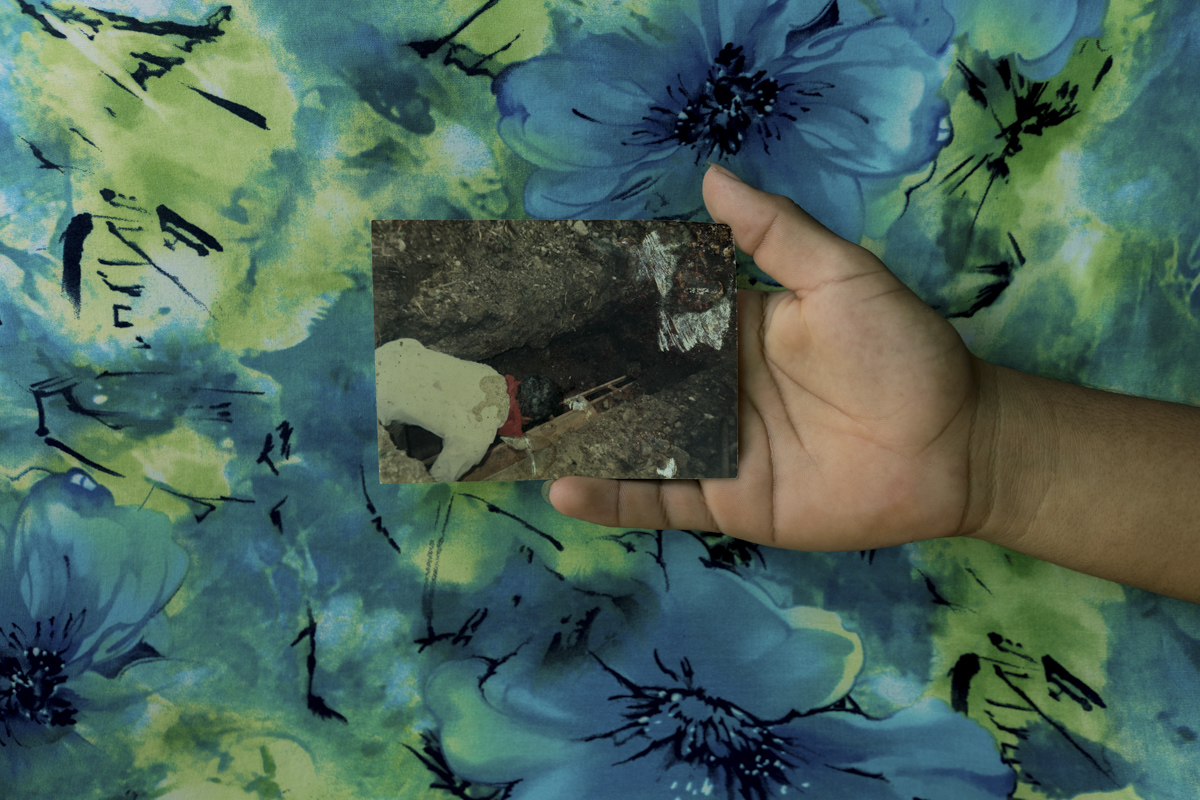

The tragedy was recorded in the family album. It starts as a memory of everyday life: Andrés and his brother wearing Bart Simpson masks, his father riding a horse, the first day of school, the Halloween costumes. But at some point it becomes the record of death: the mass grave where his father and uncle were found, coffins with flower arrangements, a family photo where most of the protagonists are now dead.

“Once a year my grandmother liked to see those photos, especially on the days when my father’s death was commemorated,” says Andrés 27 years later. He is now 30 years old and a photographer. “She kept it in some boxes that she had under her bed. But I was always apathetic. I didn’t like seeing them so much.”

The photos began to be damaged. The humidity corroded them and Andrés knew that there was a starting point there. What started with those images is a job in which Andrés searches for his family. Not just his parents, his uncles, his murdered ancestors. He also searches for the living, whom he always was close to, to find out what their dreams, their nightmares, their feelings, their fears, the meaning of war and loneliness are made of.

Andrés lives in a city called Florencia, in the department of Caquetá, in the southeast of Colombia. It is the largest city in the Colombian Amazon, the point where the Andes Mountains end and the jungle begins. On the other side of the mountains you can see the savanna. Three territories with three different climates.

He did not always live there. He grew up very close, in San Vicente del Caguán, a small town in Caquetá, an area that he himself describes as “very violent”. “It was where the FARC was,” he explains. “In 2000 it was like the epicenter of coca in Colombia. It is a town very stigmatized by the presence of subversion. It is where the most military and strategic FARC column was for a long time. It is a place where the armed actors have carried out massacres, many murders. In Peñas Coloradas del Caguán, in the municipality of Cartagena del Chairá, there were forced displacements of 3,800 people by the Public Force. And human rights violations were constant throughout the territory, in the hands of the military, the paramilitaries, and the guerrillas. ”

Over the years, Andrés came to understand that everything –violence in Colombia, the tragedy of his family– has to do with the land: with who owns it and who does not. “Colombia has a land distribution problem,” he says. “My family has not had so many opportunities in life. The only thing they has known how to do was work the land ”, he clarifies. “A lot has had to do a little for a political issue of belonging to progressive parties, but it also had to do with the strategy that the government proposed regarding the position it has in areas where there is a large amount of coca cultivation.”

When he finished high school he didn’t know what he wanted to do. The cousins he had grown up with had long since dropped out of school and none were studying. In Florencia there was an arts career and that was where he went. She had two hundred dollars and a suitcase.

He signed up for the Bachelor of Arts to be a teacher. And he went through many branches: painting, sculpture and theater. He was looking for a way to tell what he saw around him: a land of inequality and death. So he returned to photography: when he was a child his aunt had given him a small roll camera.

He finished studying and continued taking photos. He was going aimlessly, he did not know too much that world of gallery owners and portfolios. “I came to photography because I needed to find an effective way to tell what is happening to me and what is happening in my territory,” he says of those early years. “But later it turned into a snowball that was growing and I no longer need to just talk about the place where I live but I started working in other places, traveling through Colombia, going to the border and dealing with migration issues. Everything was growing in a fast way, very fast ”.

At first he thought his work was important to his family: he gave them an opportunity to talk about what they had never talked about. Now he thinks it is the other way around. “When I began to assume in a different way the narration of the conflict, I thought that perhaps it was my family who had given me the opportunity to tell what death, forced disappearance, the dreams and nightmares of those who lived through violence like this”.

With the beginning of the Peace Process, government organizations were created to face the truth of the conflict. At that time, Andrés reported the disappearance and death of his mother to try to find the body. “My parents were murdered at a time known in Colombia as the era of the Patriotic Union genocide, which was a party to which they belonged,” he says. “Talk about what was happening put yourself on the map to be assassinated by the Colombian Military Forces. Many questions we had could never be answered because that subject was not discussed. We only knew they were dead. ”

At night Andrés climbed with his cousins and his brother to the water tank of his house. In the dark they saw the military planes over the mountains: the bursts of shrapnel, the lights and the suspended gunpowder. When the guerrillas withdrew, everything was even worse: the paramilitaries arrived. Every morning the town woke up with half a dozen dead. No matter what changed, the violence always remained.

The horizon of peace unleashed a process of collective narration. “People started talking, you saw people on TV every day telling what they had experienced,” Andrés remembers. “I told my family that it was time to talk, I wanted them to tell me what had happened, how, what they felt, what disturbed them and what they wanted for their lives.”

In those talks, he was able to see how these decades of violence and death had outlined his family’s nightmares. “I noticed,” says now, “that each one had a different version and a different way of living those duels and death and how the violence left them in misery.”

In one of Andrés’ photos, two young men lie in a pit. They are on their backs and almost naked, each wearing only a small slip. They are the brother and cousin of Andrés, who in that position recreates a real scene from 1993, when someone photographed the bodies of his father and uncle. In the original photo they are covered in mud.

“When I went with my brother and my cousin to take that photo, I made jokes: dude, lie down there,” says Andrés. “It was a calm, trustworthy environment. They still did not understand that I was doing a reinterpretation of the pit where my dad and my uncle were find, but they took it as something a little strange that I did,” he recalls.

Each picture was the opportunity for a meeting. In the montage of the scene the opportunity was opened to speak again of their dead. For him, the project allowed him to be calmer so he could say out loud that his family did not deserve what happened.

The work is not finished yet. Andrés titled it Wreck family which can be interpreted in several ways. For him, it is a growing process, which accompanies him in the search for his mother’s body. It is a process of denunciation and memory, of working with pain and building art with the raw material of history itself.