Gato Negro Ediciones is a small publishing house based in Mexico with international distribution. Made up of a team of three people, in the last six years they have built a catalog of about 150 titles, full of strange jewels ranging from photobooks to essays and poems, with male and female authors from all over Latin America and the United States.

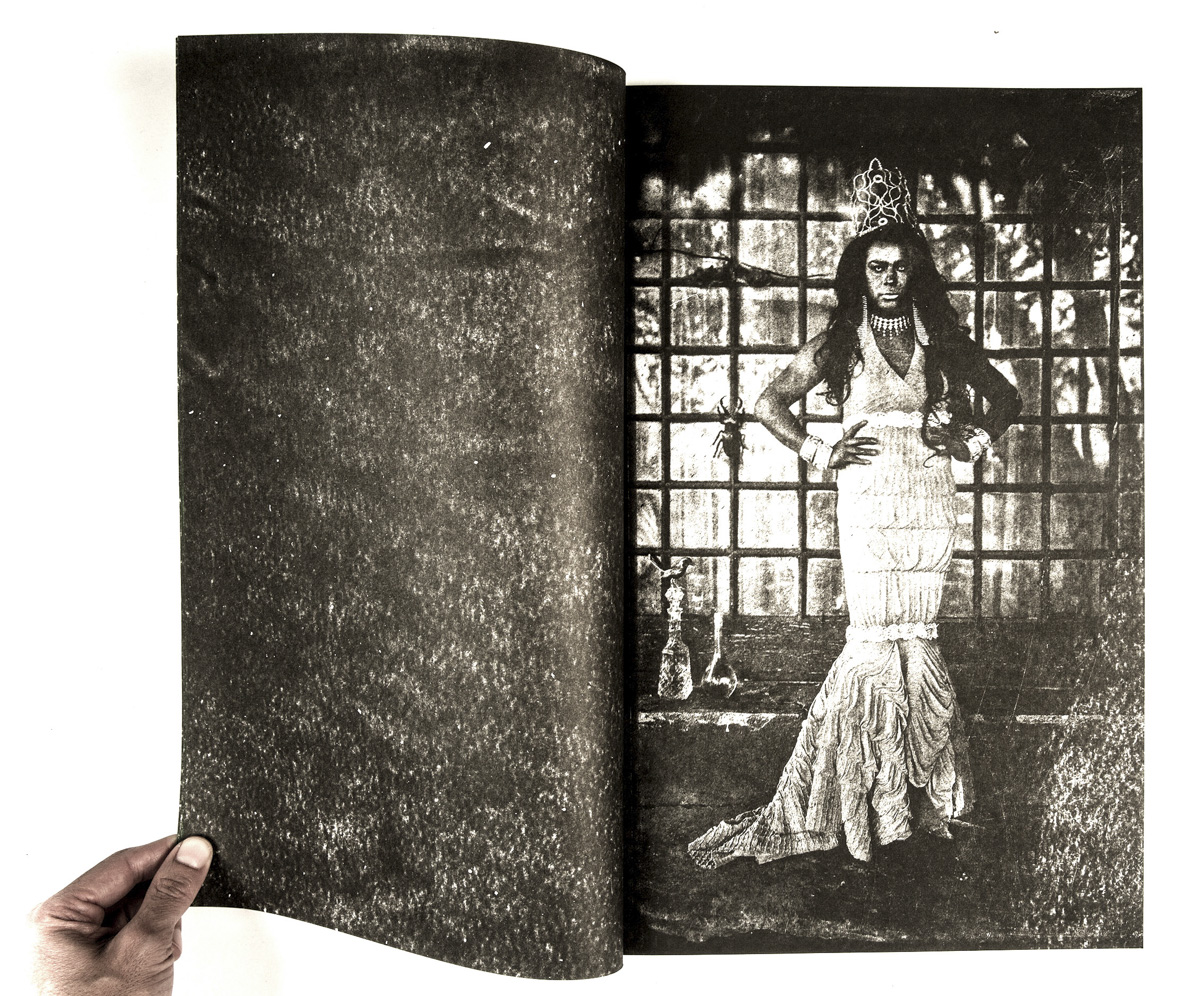

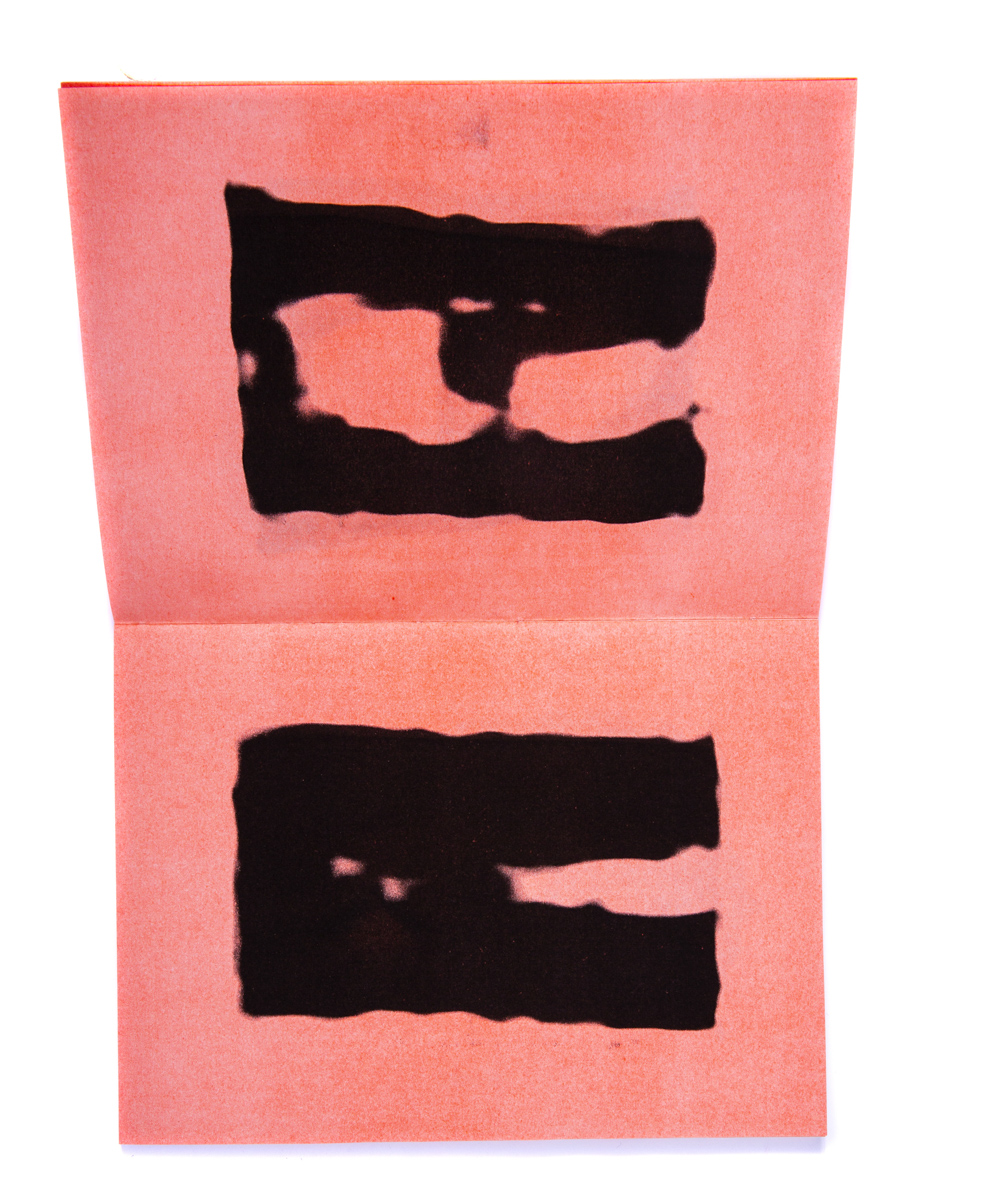

At the beginning it was a project thought from design, a way of publishing on a small scale, with low cost and always favoring freedom and experimentation. “This is linked to how we print with the RISO machine, an electronic duplicator,” explains photographer and editor León Muñoz Santini, one of the founders of the publishing house. “At the beginning, our idea was to be an autonomous space, with book format content and with freedom and the least expectation possible around everything.” That all encompasses topics, forms, techniques, procedures.

They were betting on circulating from hand to hand and mouth to mouth. Cheap printing allowed them to take risks, freeing themselves from the fear of business failure. “This way you can publish things that would otherwise be very complicated,” explains León. They gave priority to titles with small runs rather than few titles with large runs. In terms of printing, they say, it is more what a RISO does wrong than what it does right: its charm lies in the imperfection.

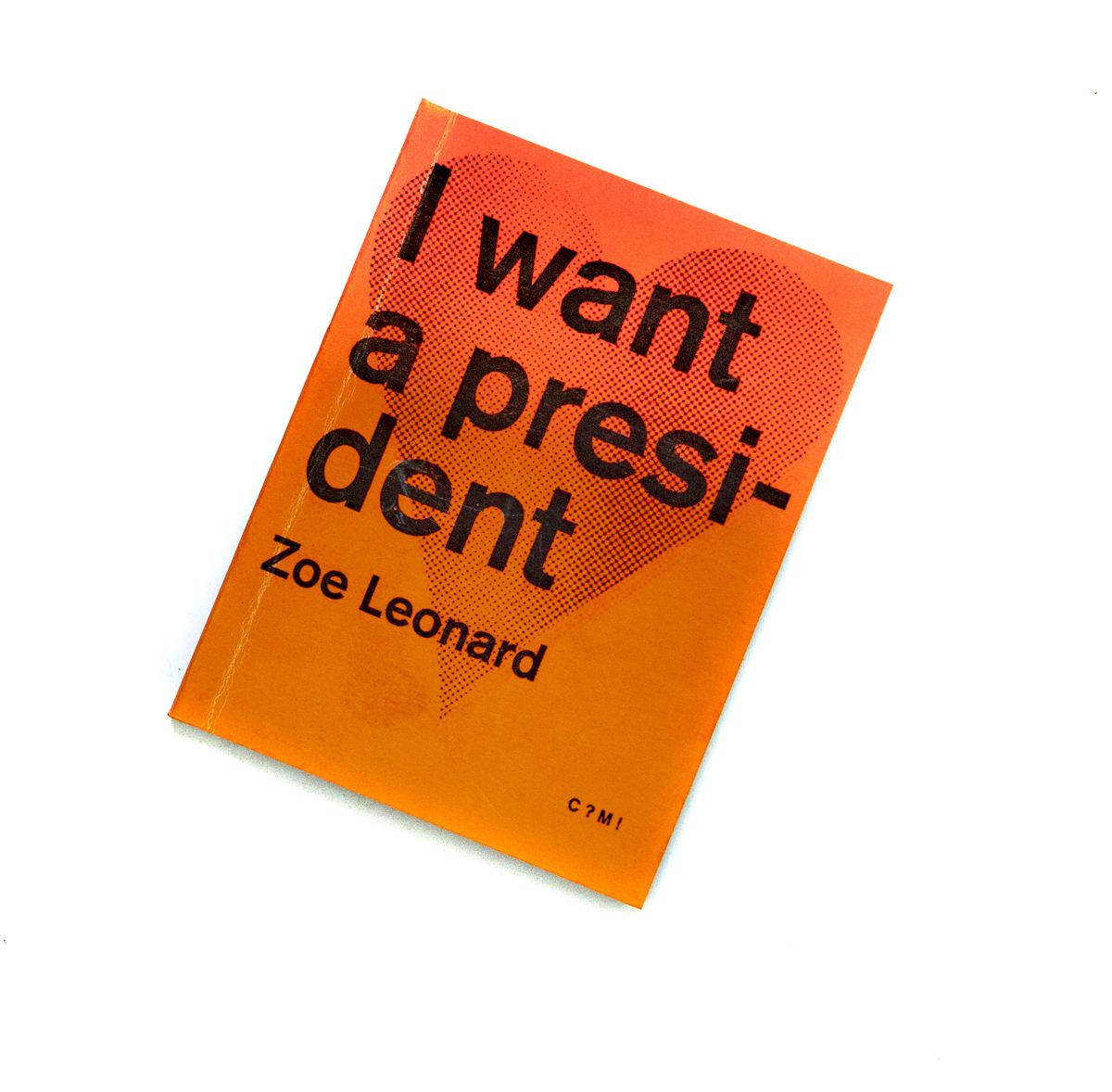

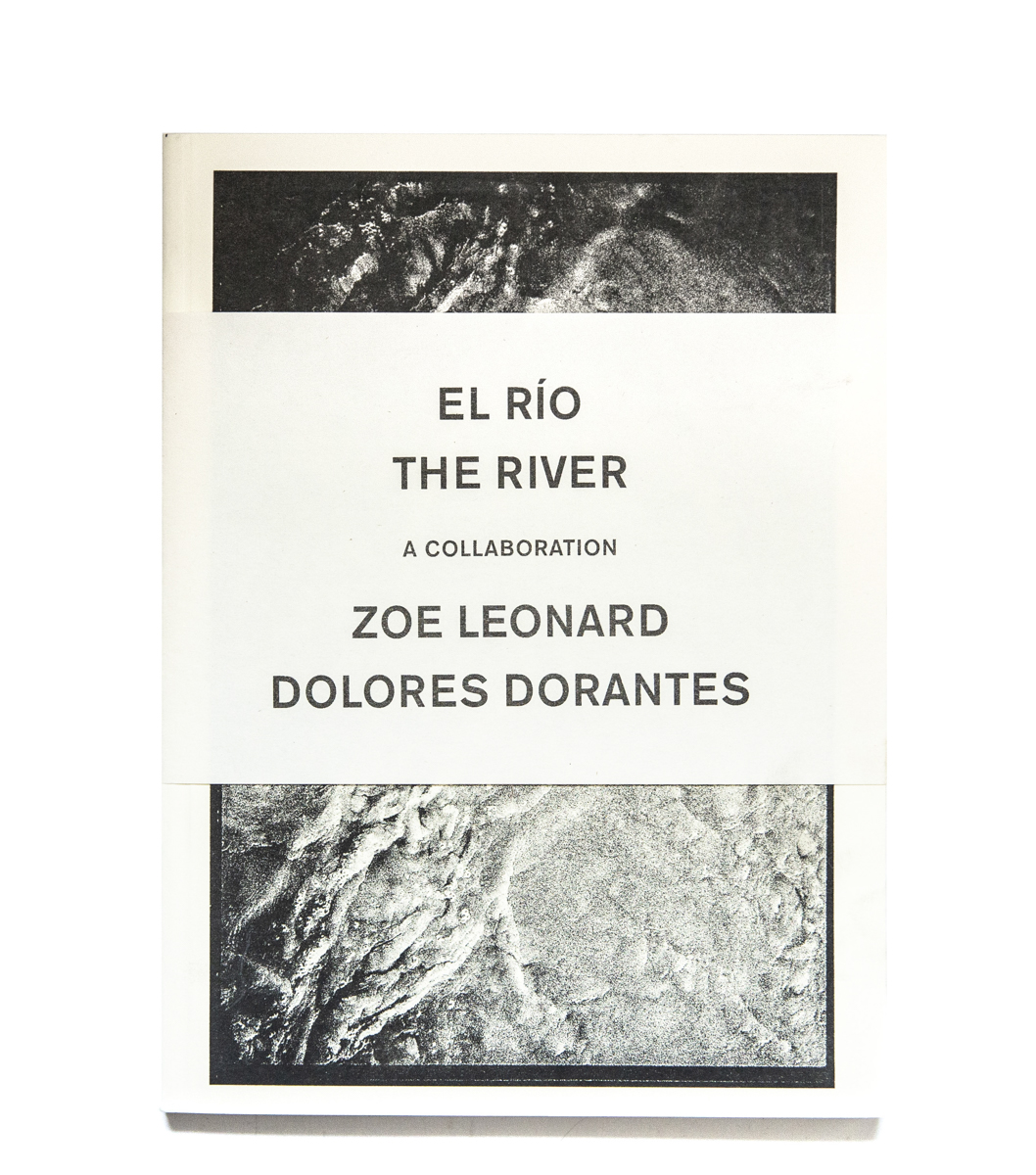

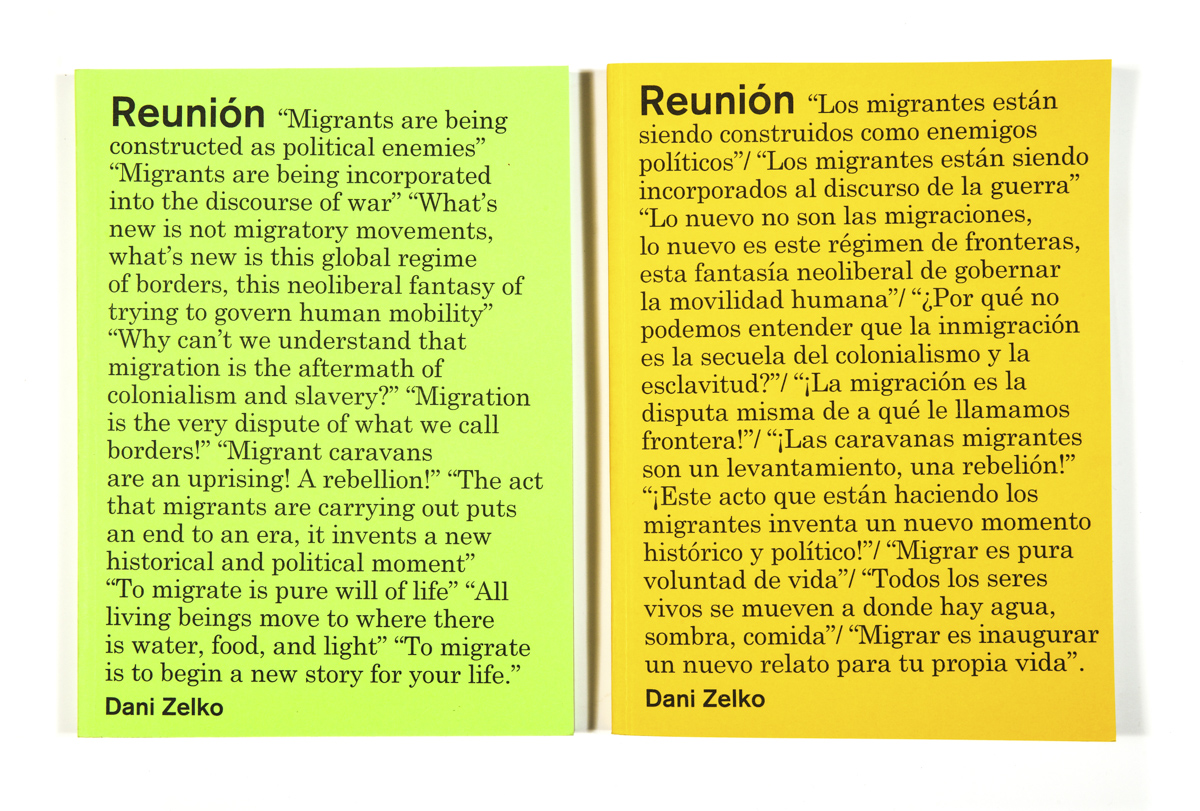

Its catalog is built on the margins of the publishing industry. There are books of poetry, essays, photography and art that, without looking for it, first crossed the Mexican borders and then the Latin American ones. “What ended up happening was that, for better and for worse, the books we make circulate more abroad than here,” explains León from Mexico. This journey beyond what they expected made them aware of the center-periphery relationship that conditions the circulation of intellectual, artistic and cultural content. That awareness changed everything: “For a few years now, half of the books we make are in English with the idea of being able to circulate in those spaces, carrying content generated here, trying to subvert this center-periphery dynamic to which cultural content generated in Latin America is always subject to.”

That work model based on a small run of books that were passed from hand to hand, which were trafficked as a password or a secret, was transformed. “The possibility of circulation with another currency became an economic model itself”, explains León. What started kind of by chance became super calculated: up to that point, the plan was that there was no plan. But the project grew and became somewhat unmanageable. They have not yet been able to resolve the contradiction between having the catalog of a medium-sized publisher with the structure of an artisan publisher

Accustomed to living in dichotomies, Gato Negro stands in front of the book market as a different model, clinging to the practice of what is possible, understood as what they can do for themselves.”I am not saying that our model is better, or worse, or etc. but it is simply different and is closer to what is possible.” And publishing, they say, is a way of attaching to the book as a fetish, to that meaning that goes beyond its materiality. León defines the book as a promise of survival: “There are certain types of arguments, notions, which can only be stated in a form of abook and that is what our work is about.”

“I find interesting the idea that producing a book is more or less accessible in terms of money and taking away the grandiose gesture to publishing,” says León. Lower the expectation of the book-object, “to that idea that every book must be a very great idea or a reflected life project.”

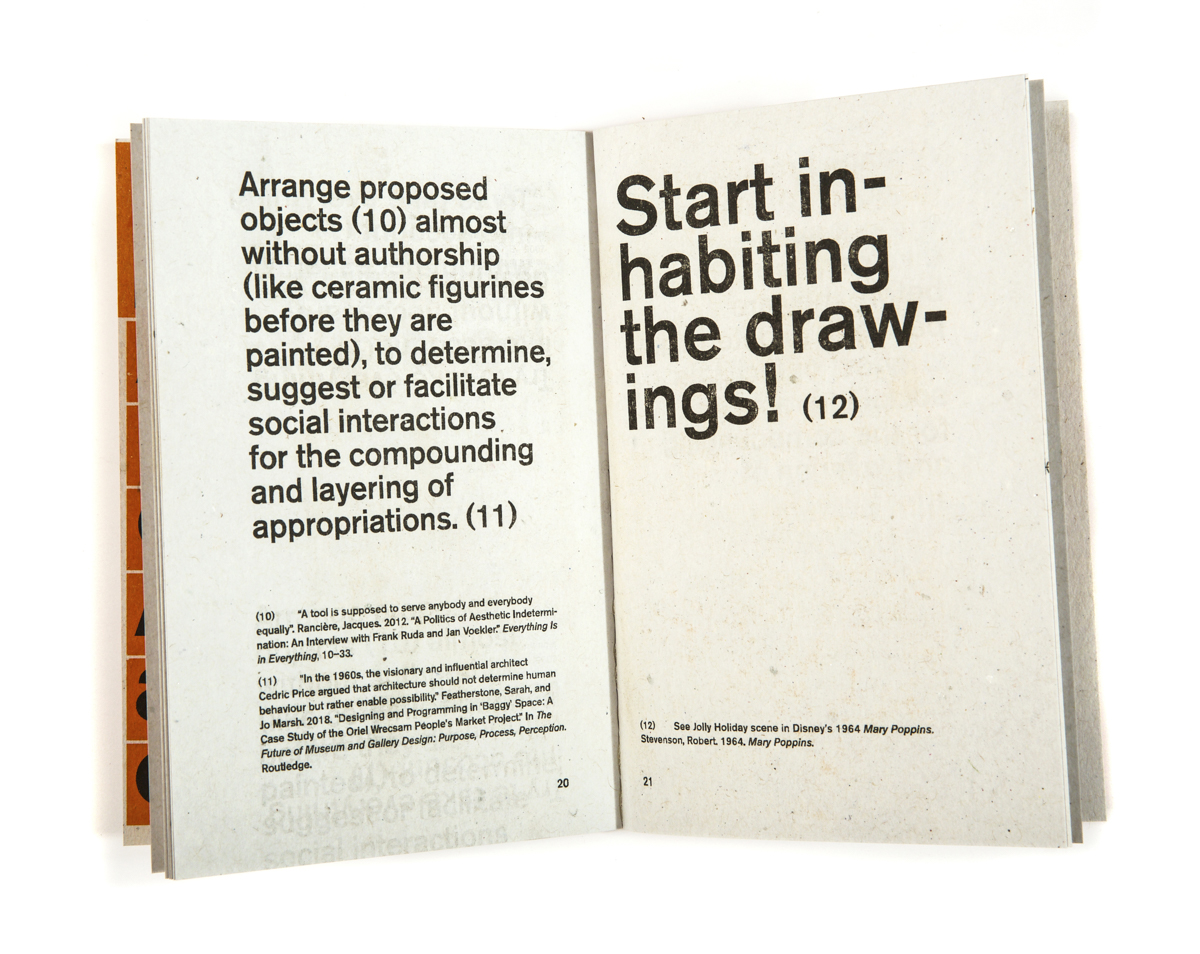

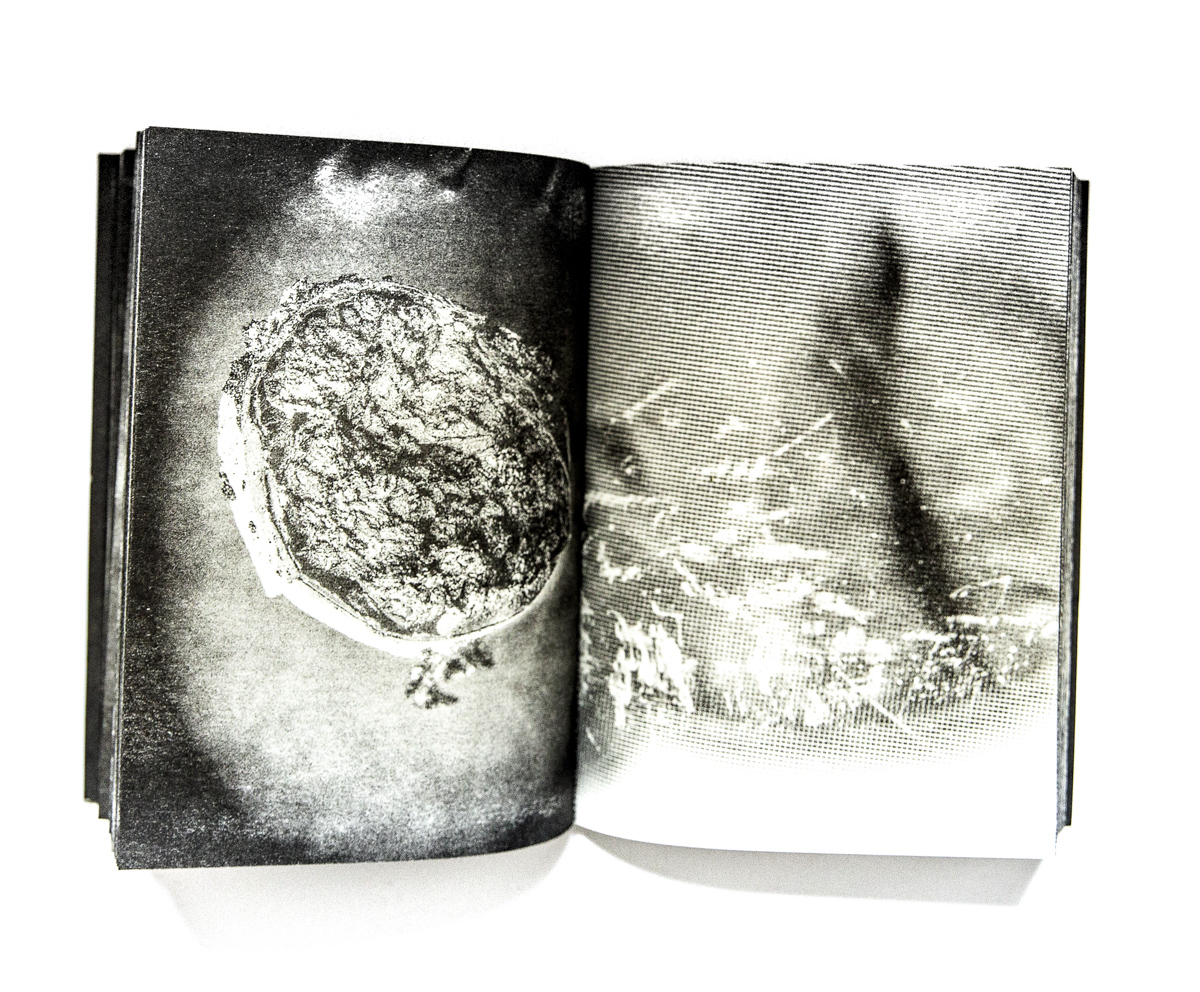

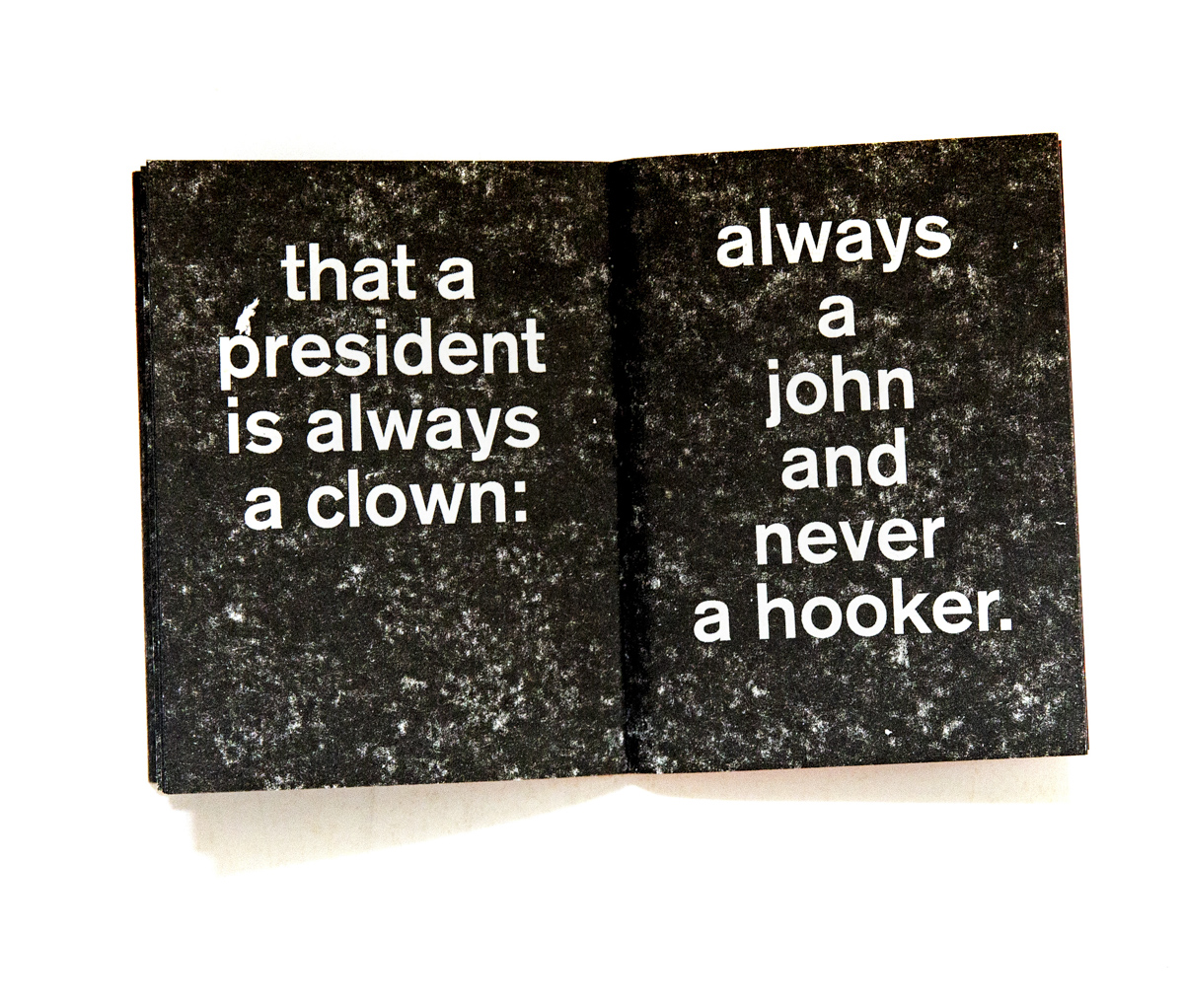

Photographic essays on Ciudad Juárez and on post-Franquism, books of poems made from other people’s verses, theatrical texts about a Paris without the Louvre, political manifestoes, philosophical essays: Gato Negro’s catalog is impossible to label. It includes rarities such as Nostalgia, the photo book without photos of the North American artist David Horvitz, who erased his entire digital archive and in this (not) photobook compiles brief descriptions of all the images in this missing archive. One page says “self-portrait while driving,” then the filename, time, and date; “greeting the sunset”; “Moon”; “the nest of a hummingbird”; “a fox in the night”.

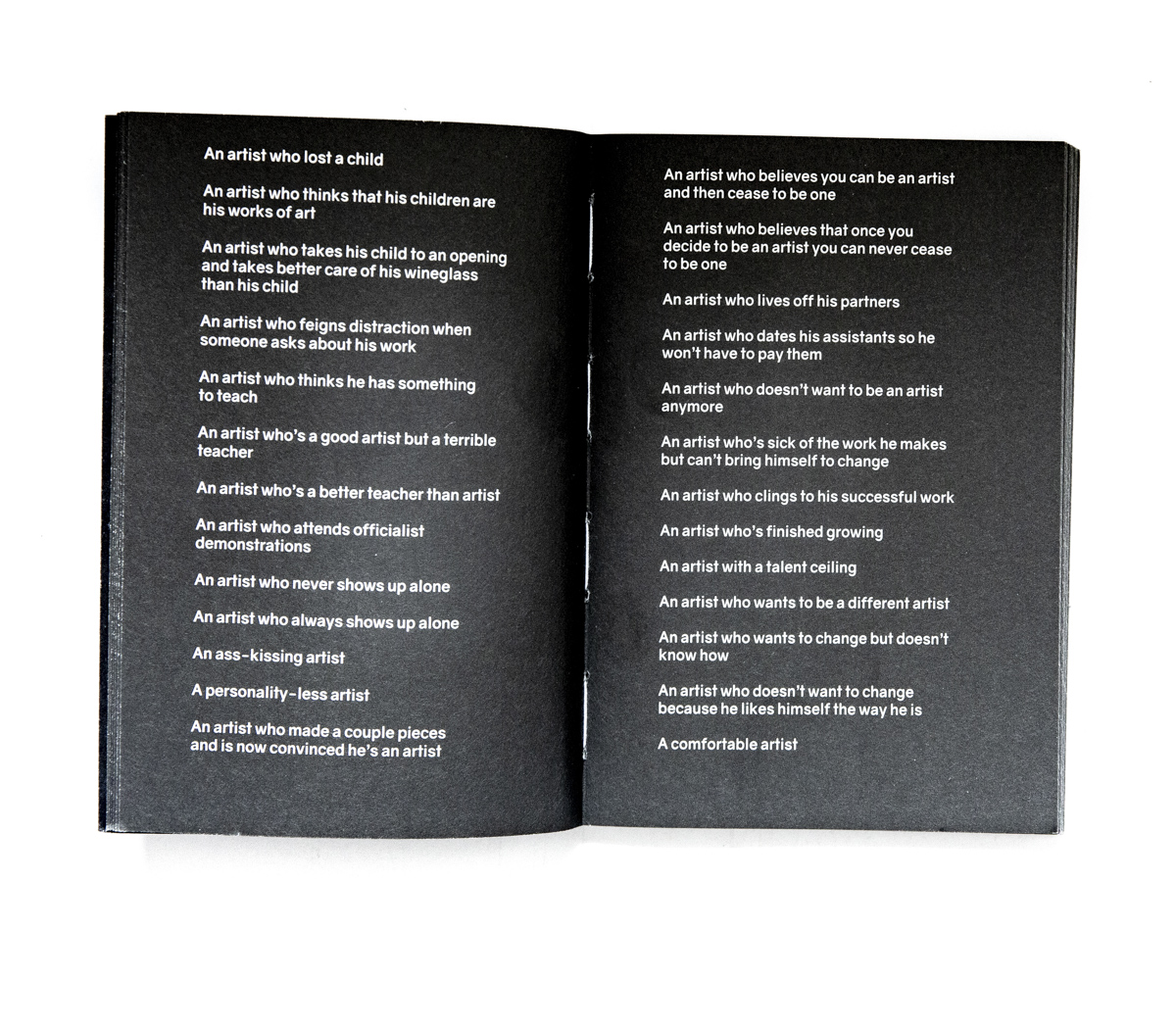

In An Artist, the Argentinean Malena Pizani brings together 1,500 descriptions of an artist made, as León says, “with bad temper and a very precise sense of irony.” “First it was a video piece that was a voice-over on a black screen and then a small edition was made in a gallery called Big Sur,” says León about the process. When they found out about the book, it seemed to them that it could be circulated anywhere, so they proposed to Malena that she translate it into English and they did not print it with RISO, but in Offset. They made a huge run, of a thousand copies, and they never regretted it.

To print is to resist, their latest book, is a compilation of graphics of the Chilean resistance that was born in the heat of the popular revolts that began in October 2019. “Everyone in Latin America saw what was happening and we saw how many friend and comarade people generated this ‘response’ in graphic terms to the brutality and barbarism of Chilean fascism “, says León,” and that was relevant and it was worth circulating it and having it become content in printed matter.”

They thought of it as a first “memory and preservation exercise”, an object that will remain when the bytes of social networks where the riots were transmitted in a loop during the last months of 2019 have been dissolved in the digital tide. The book also resists.