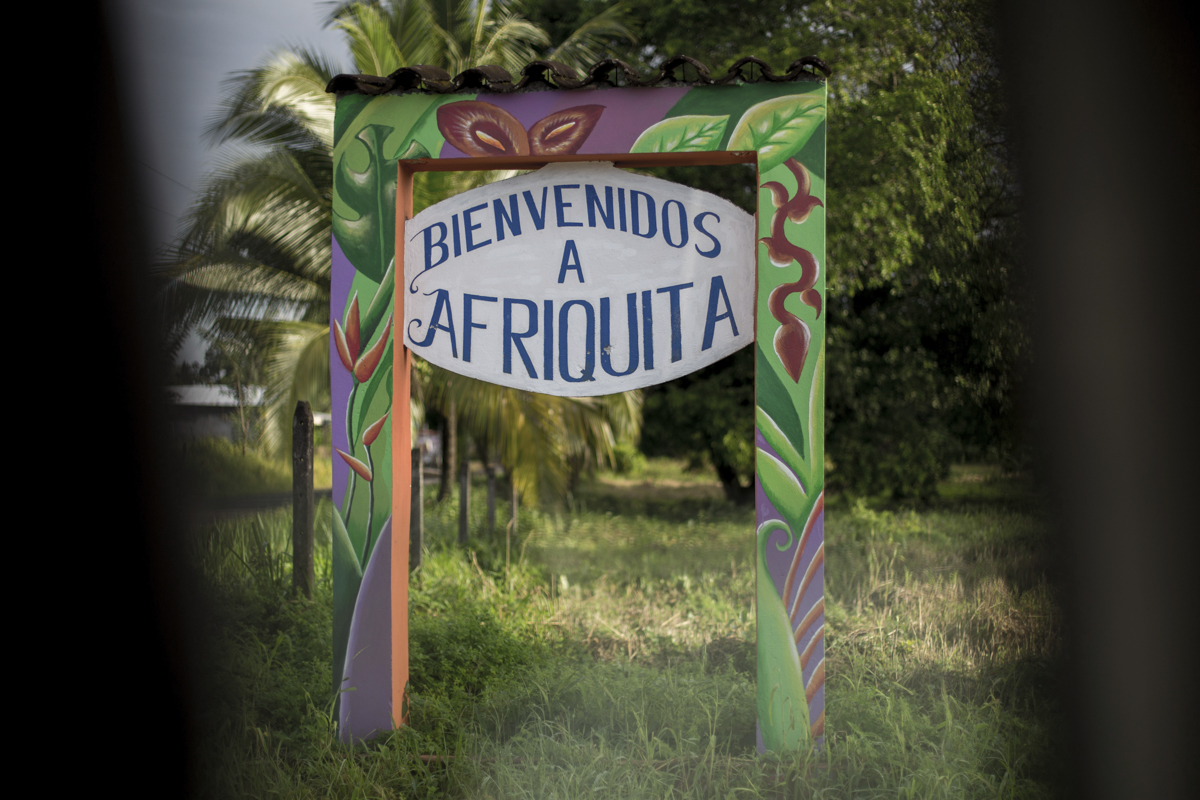

Toponymy is the set of territory names. The Nomad Collective, born a decade ago in Costa Rica and expanded to various latitudes, thus named their work in the province of Limón, where they toured different cities, countries and even continents without leaving the Route 32 that connects that province with San José. On their journey by car they went from Africa in Guácimo to Brooklin, Cairo and France in Siquirres; from Venice, Boston and New York in Matina to Jamaica Town and Argentina in Pocora.

There are those who explain this choice of names as a product of the immigration of Afro-descendants who built the railroad at the end of the 19th century and who had some connection with many of those places. The Colectivo Nómada does not stop at the origin: as in much of their work, they focus on the present; in the daily life of the communities that inhabit these regions. The work was done with the support of the African American-AECID call for audiovisual projects. In this interview, its authors speak in a choral way about the group and the project.

We started in 2008 as a group of friends from college. Originally we were twelve and now we are four. We were a group of students who worked for the media, at least those of us who were in Costa Rica. We needed an alternative to be able to publish because we were very subject to the editorial issues of the media in our country, where there is no photograph linked to recounting something in depth. The idea of being collective was an escape valve.

We like to tell stories related to the everydaylife. As a group, what interests us is daily life, what could be called “simple normality.”

Last time we said that we are a kind of “compound monster”. One is the heart, another the brain, another is the feet that move. Who is what? We take turns! This is curious because it is thought that working collectively implies that we are all a brain, or all of us a heart, but we have that particularity of disagreeing with each other. Even so, we managed to get work done and each one to keep their mentality without necessarily having the same line.

At some point, some assume the role of managers, another of editors, another of photographers and another of writers, and that varies. The monster changes according to the project, the way of moving the project as well. Among the four of us, as a more refined group and after many experiences and many people working, we have already reached a good level where we know what each one can contribute to each project.

There is no individual signature on most of our works. Each one has their projects on the outside but as a group we are not interested in having a firm footprint within the group. What we are interested in is defining ourselves as a group that promotes photography in our region.

We do not have very great ideals or aspirations because we come from nothing and if we continue from nothing, at least we have managed to survive, during all these years, with photography. Obviously if we managed to get our images and our work out of the region it would be excellent, it is great but we do not have that intention of being THE photographers, the photographic trophy hunters. Nor is it that we are going to take photographs with empty or meaningless speeches. If it makes sense to us and if it is honest, then it is valid.

We have that need to be hanging around and watching, and that has also made us not be in the competitive industry but rather from the side of continuing to do. Many of the groups that were in when we started no longer exist. That is why Nomad is also a mentality.

The collective helps us to manage and we have learned a lot about that part because in this region if something is not managed, it is useless. We see how we continue, how we finance ourselves and we seek support. In the first stage the collective was a lot to produce for nothing. In other countries people produce and they know that there is an infrastructure that is going to sustain them, or that a medium is going to buy a topic from them and here that does not exist. You knock on a door and rather they tell you that they are doing you a favor.

We have adapted to the issue of the pandemic because we have been working and talking virtually for a long time. It is very rare that we meet in the same place, so most of the time we meet through these means and now in these times of pandemic, it reminded us of the way we always work, we only reinforce it now.

Now we have the advantage that we are close but we see each other from time to time. When we visit we try to see how to do something, at least a workshop, talks or even go out to do.

Toponymies very important because we made an exhibition in two regions because there is a very big separation between the capital and the Caribbean region. We were interested in taking this work to San José, to the capital, so that people would become aware of the issue but without forgetting the protagonists, the photographed. So we also took the work to Limón, which is the region where it was produced.

Sometimes, the impacts that interest us as a group have more to do with the local than with the international. We feel that we are working on a small scale but it is a scale that manages to be more significant with respect to a possible impact.

The Toponymies project consisted of photographing places that are called big cities. In this region called Limón we look for “New York”, or we work in “Venice” and that was the intention of the project and visiting those places helped us to have an image of that Limón that is preconceived.

In Toponymies we were all on a car, we had the opportunity that Tona come from Mexico and we were able to have a very intense experience because it was arriving, photographing all day, looking for places that possibly not many people had photographed because they were very specific locations, very little. In those periods of time when we arrived at night we sat down to debate things, we would edit on cameras.

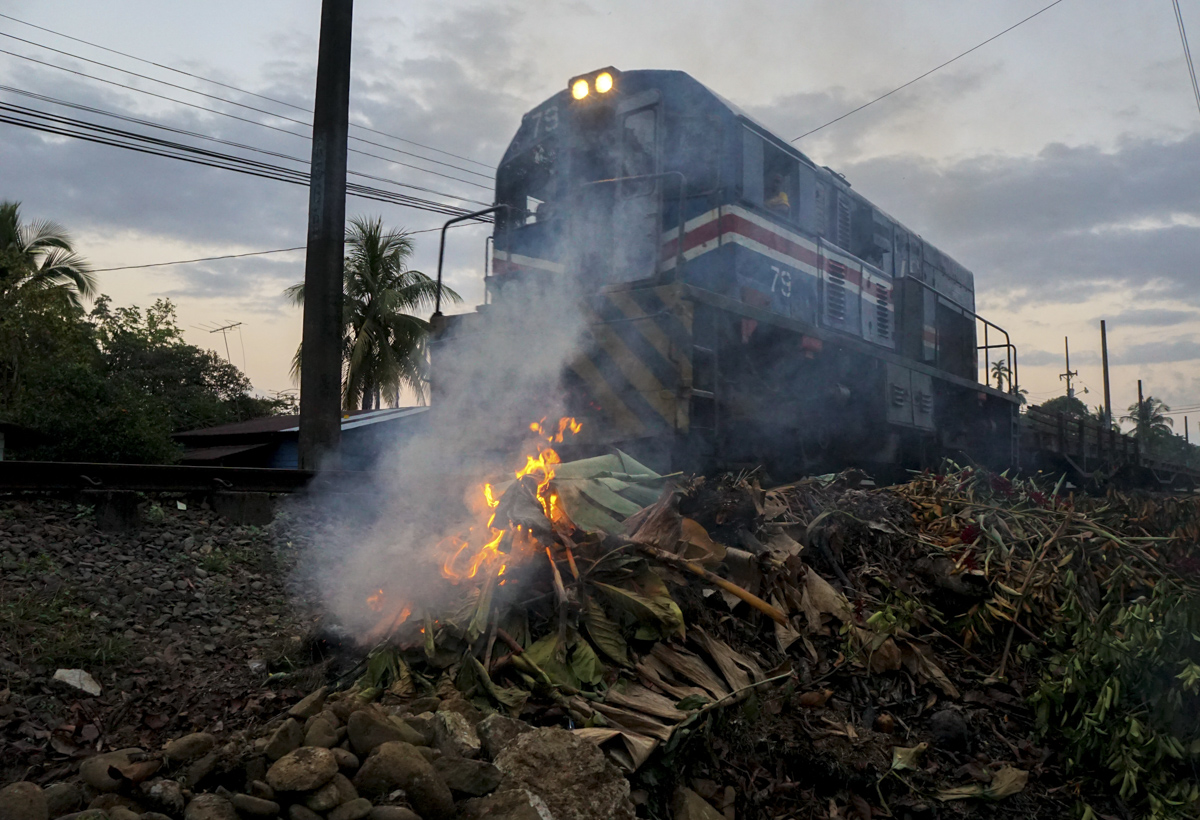

We made a fanzine to distribute, it was linked more to that side because in those localities the photography was almost missing, not only because of the distance but they are towns that were left on the train track and in many of those towns there is no tradition of that people come to take photos. In the fanzine there was the map of the route, which was important more than anything because of the names of the places. It was as if we had gone for a walk to Venice, to New York, to Toronto in just a few hours.

Many problems have to do with arriving at a place and wanting to find the exotic side. Why don’t I photograph a Santeria? For us it is more like arriving at a place, loitering and photographing people as they are, more the everyday. We question those paternalistic, neocolonial stories. We approached Toponymies because we began to have a sense of identity towards what was happening in Central America. There is a complete lack of knowledge about Central American photography. Most photographers are from outside who come to work in several problematics. We polished that vision over the years so as not to see the territory as something exotic or as a safari.

Working in the heat of Limón was something that determined the way we took photos because we worked very early or very late at night. We had to relax and those were experiences that marked us. The experience of taking photography in the car led us to develop a technique with the car lights and it helped us take photos at night.

There we live in a house where one of the members of the collective lived for a long time. And that was also enriching. Beyond exploring the territory we find the definition of Nomads. We like to feel the territory and then many times we go to the places and collectively document what the territory crosses us.