Lorena Velasco remembered that her maternal grandparents had an orchard, that they braided her hair, but not much else. Actually, she hardly knew them when she decided to get close and take pictures of them. She did it in the middle of a family fight over an inheritance, so her intervention not only allowed her to recover her own history but to intervene in the conflict. She is convinced that, through the image, certain personal situations can be “decanted”. So when the pandemic hit, she brought the tool of photography to her nine-year-old daughter. Together, they thought about the scenes to represent the anguish that appeared, such as, for example, the fear that their kitten would be infected with Covid-19. “Right now I’m immersed in that personal universe, at this moment this is my transit, I don’t know what tomorrow will bring me,” she reflects.

She is a photographer and the president of the Universitary Photo Club of Popayán of the Universidad del Cauca-Colombia. In it there is a double sensitivity: the introspective and the collective. In 2018, with a partner, she realized that a horizontal platform was missing where emerging female photographers could publish without too many “buts”. This is how Fotografas Latam was founded. They opened an Instagram and never imagined that their need was the same as that of “thousands of Latina women.” Today it is a collective that is dedicated to the visibility and promotion of female photographers in the region and “highlighting the role of Latin American women in the visual medium.”

How were your first steps in photography?

My approach to photography is through a group of photographers from the city of Popayán, a city in southern Colombia where I live. When I arrived at the University Photoclub I found a diversity that fed all my concerns about the photo. They helped me, in a technical way, to overcome obstacles and then to go deeper to find my own path, my essence. We did trainings and trips. I came across references that marked my work.

The first thing I learned was night photography, then the trips. Then, documentary: I worked a lot on social photography. And then I decided what my path was: I was interested in decanting certain personal situations through the image. Self-portrait costs me, it is something that I will have to process over time. But I was interested in talking about myself through my body and through the people who influenced me. In that sense, I started a project with my maternal grandparents, they recreate that childhood. My grandfather has just passed away, but at that time they were very lonely and going through a difficult time because there was a separation of assets due to a family fight over an inheritance. They did not want to leave their place. I had never had contact with them and we had to build a relationship from scratch.

In fact, I had very vague memories of them. They made braids in my hair, I remember the garden, the yard. But I had no emotional relationship with my grandparents. We then began to work, to recognize each other. It was something that marked my life. It was a special moment, I was shocked by what was happening.

I was taking pictures and they started to work as a series. Later, in a workshop we began to settle the idea and I began to investigate surnames, origins. We discovered that the surname “Velasco” means “children of little crows.” And there the project was transformed into a mythology: my aunts fighting for a territory as if they were crows, taking the land from my grandparents. I was thus creating a personal position, because until that moment I had not had it. The series is called “Memorias del Silencio” because he was deaf. The way we communicated was through letters, through little pieces of paper that we wrote on the wall. A very beautiful relationship.

With all this, in some sense what I was looking for was a little talk about myself, without reaching the self-portrait. I wanted to talk about the absences, the shortcomings, about what I felt I was missing. I would print the very large photographs and they would stick them all over the house. All this led to a rapprochement. Roughness was smoothed out and we all began to understand the different positions in the family.

In times of Covid, did the pandemic also lead you to an introspective search?

Right now, in a pandemic, I also began to talk about my nine-year-old daughter and the anxiety caused by the confinement: the visual stimuli and all that information that reaches our ears. She was very concerned with the news: that cats were going to be infected, for example, because she has two cats. They were volatile things perhaps, but transcendental for her psyche, which triggered an anguish in her and we dealt with it through her photography. We then did a staging where she participated, taking the images according to her dreams and her texts.

Is it the first time that you involve the person photographed on the project?

It’s the first time. With my grandparents I had the concept a little more in my mind. Not with Manuelita, with her it was a collaborative work.

Would you do it again?

I feel more comfortable doing personal things: when they are such private situations, talking about it from the outside is very complex. I can talk about these sensitive things from the full knowledge because it is something experiential, that is why I take the liberty of sharing it and speaking about it. If it were a project with a different theme and with characters outside my environment, it would be a little more complex.

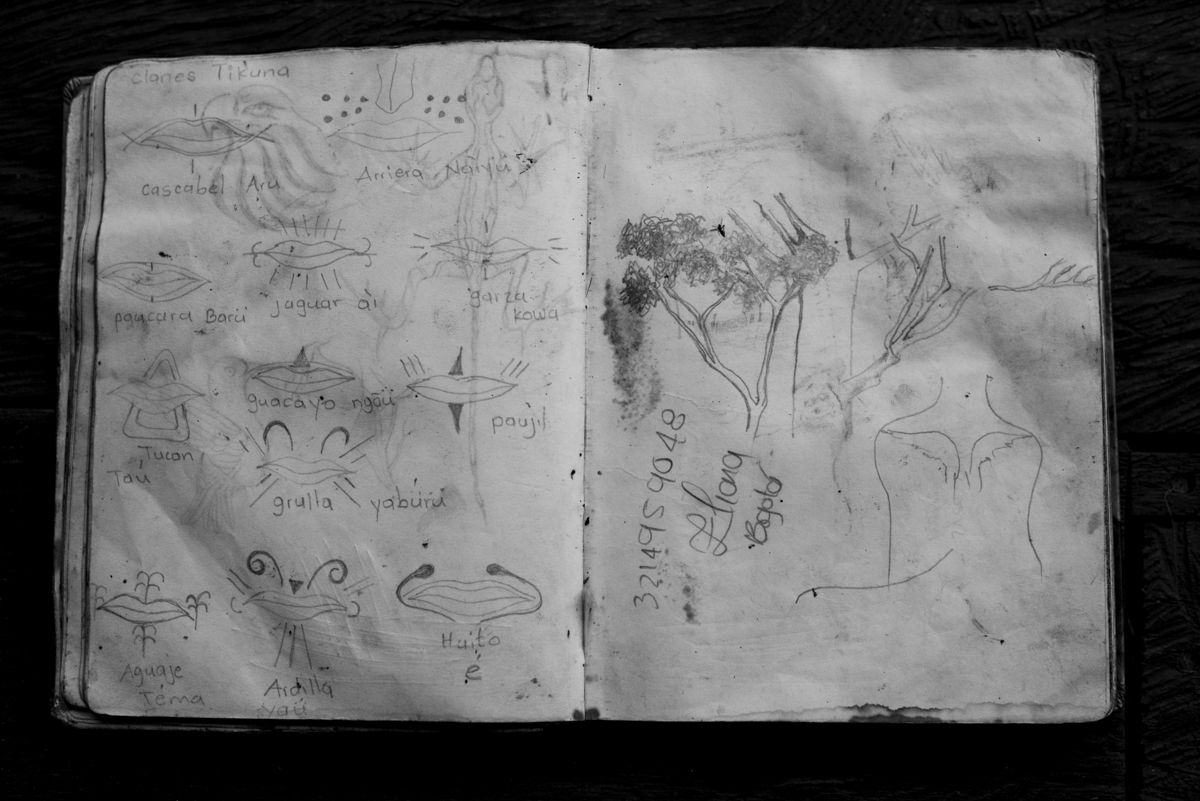

However, I do it and I have done it: my first project was called Los niños del agua I did it on Amazon. The idea is to recreate how the river started under the oral tradition of the Ticuna children. It is a representation, it is documentary but it has some fiction. So, I have done it since it is a representation of their stories, but each time I work and each time I enter that universe that appropriates me, it is more and more personal. Every time it costs me more, it is more complex. One wears out, one surrenders with everything when taking such intimate photographs. Surely later I will release a little of that pressure, but right now I am immersed in that personal universe. Right now this is my transit, I don’t know what tomorrow will bring.

How did the work in Amazonas come about?

I went to a workshop and it turned into something very beautiful, which was my first project. I remember it very fondly. I remember meeting a Colombian photographer, John Quintero, who was working for the BBC. I traveled with him on his expeditions, without much interest in doing something specific. I didn’t have anything mind, I was expecting to be surprised. In that visual narrative workshop I found many things that struck a chord with me.

The fact of being a mother, I think, made it easier for me to get closer to the children. I could communicate with them, they trusted me. They began to tell me their things, their grandmothers too. And the following year I came back with a more strong idea to finish the project.

While you are focused on super intimate stories, you are the co-founder of a great regional collective such as Fotografas Latam. How did this initiative come about?

In 2018 we were experiencing “Me Too” at its peak. With a friend, Fernanda Patiño, whom I met in the Amazon, we realized that there was no horizontal platform, without so many filters to published. She is from a city here in southern Colombia, we are both from peripheral cities. That also generated a link, we are from the province.

We were both photographers and we knew of some feminist initiatives that published some established photographers, but we wanted to give space to those who were starting, who were perhaps insecure. We wanted to contact us, put together a dissemination platform for emergent photographers. Because Fernanda and I were emerging, then that is also almost autobiographical.

We created an Instagram account and put two hashtags, but we never imagined that our need was that of thousands of Latin women. It had a huge reception and the selection process was a success. In fact, many established girls also wanted to participate. That was an incentive and a great encouragement. We were starting to get attention and we were putting ourselves on the map. It is born without any pretense, we never plan or imagine it. We said “let’s do an instagram and see what happens.” The first day we had 158 applications and we were two complete strangers.

You organized the first Latin American Female Photographers Congress in Popayán in 2019…

We did the first Congress and it was very interesting. We wanted to do it here, in southern Colombia, in the place where this project that crossed borders was born. In Colombia, training in photography involves traveling to capital cities. For this reason, bringing these training, academic, reflection and dialogue spaces to the province, decentralizing the photographic movement, is a premise for Fotografas Latam. 430 people came to Popayán from all over Latin America and we had a photography contest with more than 400 applications. A contest had never been charged in dollars in Colombia, but we had to finance it, since we never had support from institutions, we do everything freehand. Before we were María Fernanda and I, now for exhibitions in another part of the world we have a team of five girls who have strengthened ties and who have been fundamental pillars for growth. Things are happening, we have never forced them. We have only received love from the entire collective.