At 23 years old, the Bolivian photographer River Claure has just published a version of The Little Prince in Aymara, a work in which he crossed the classic story that marked millions of childhoods with the Aymara identity from which he comes.

River is the grandson of peasants who migrated from the countryside to the city. He was born in Cochabamba, Bolivia, where he studied performing arts and visual communication. Later he studied contemporary photography in Madrid. At some point of this process, he typed “Bolivia” into Google, and clicked on images and pressed enter. The result did not represent him: there were stereotypes, he noticed the search of a supposed purity that didn’t fit.

“There is a ch’ixi world, that is, something that is and it is not at once, a heterogeneous gray, a motley mix between black and withe, contrary to each other and at the same time contemplementary”. Thus begins the Ch’ixi Manifesto, inspired by the ideas of the thinker Silvia Rivera Cuscanqui, ideas that also run through River’s work.

“How can I not consider myself ch’ixi if I wake up, watch Netflix and chew coca?” Claure wonders. “I have practices ‘not very from here’ and also ‘very from here’. I think my statement as an artist is related to looking at heterogeneity, to observe gray identities.”

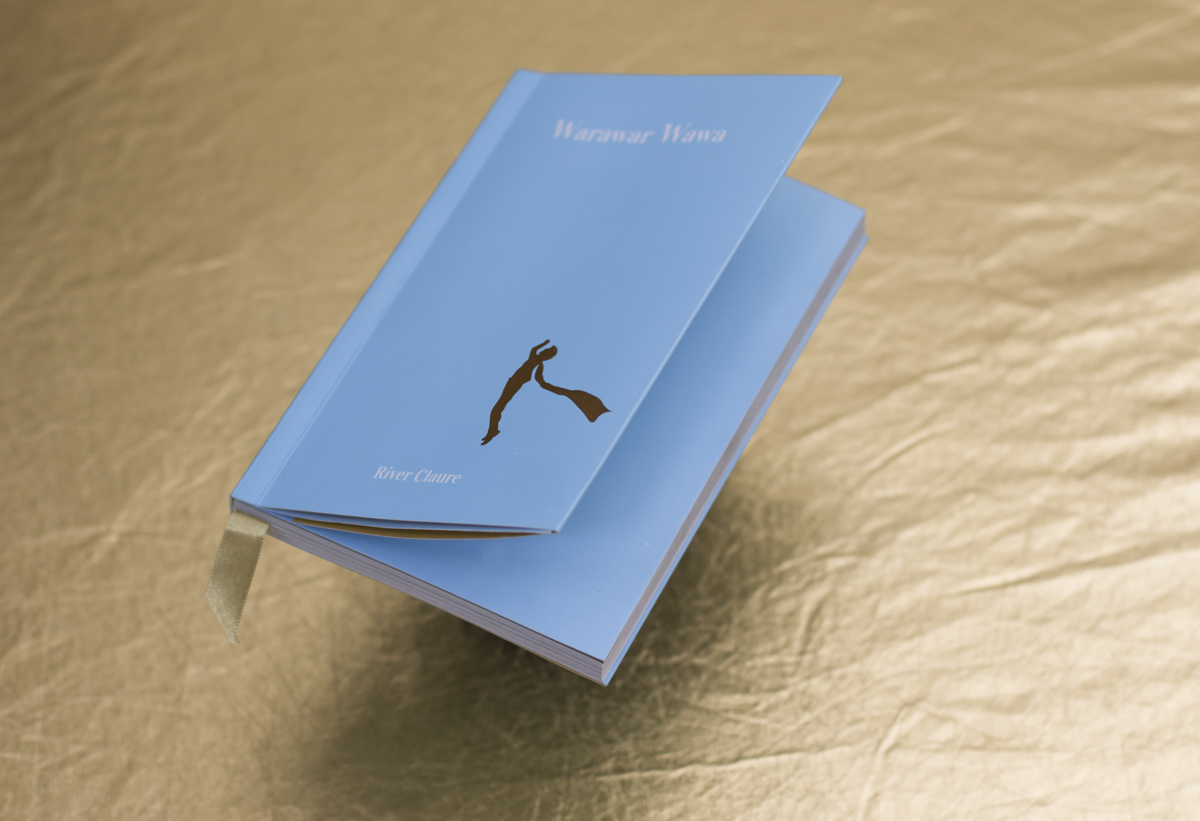

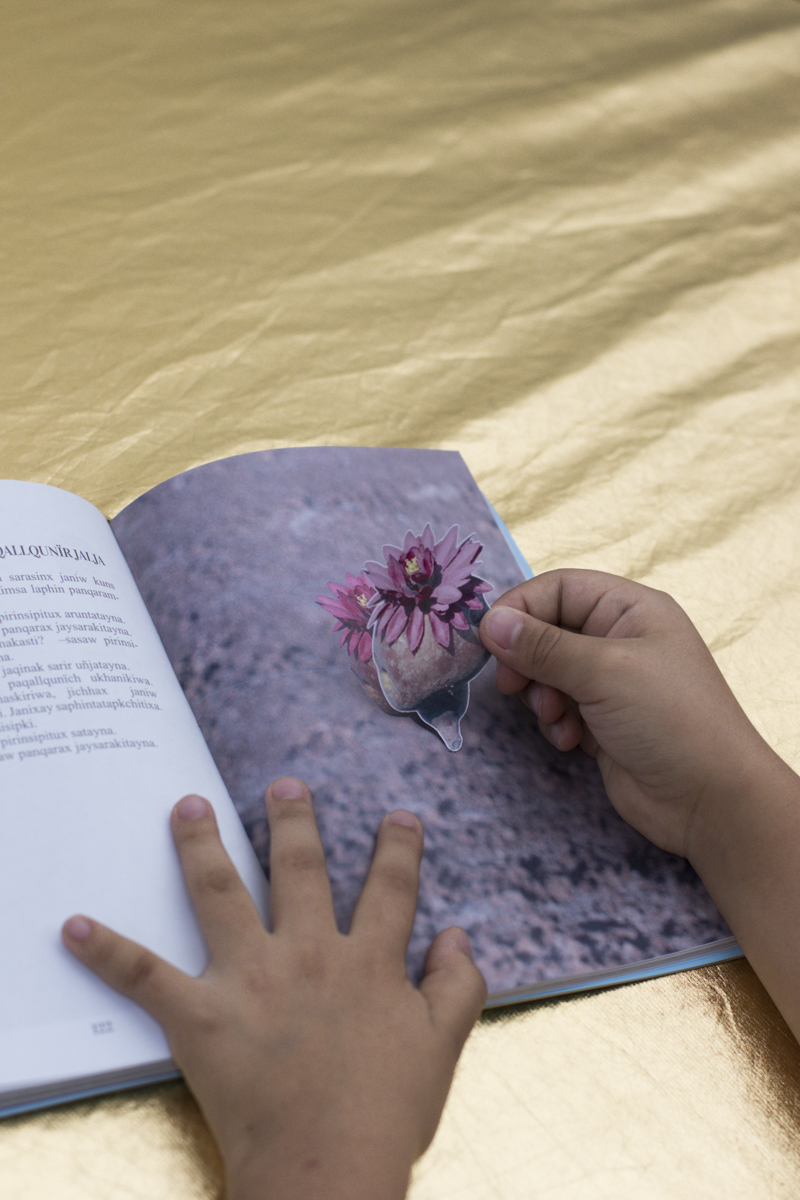

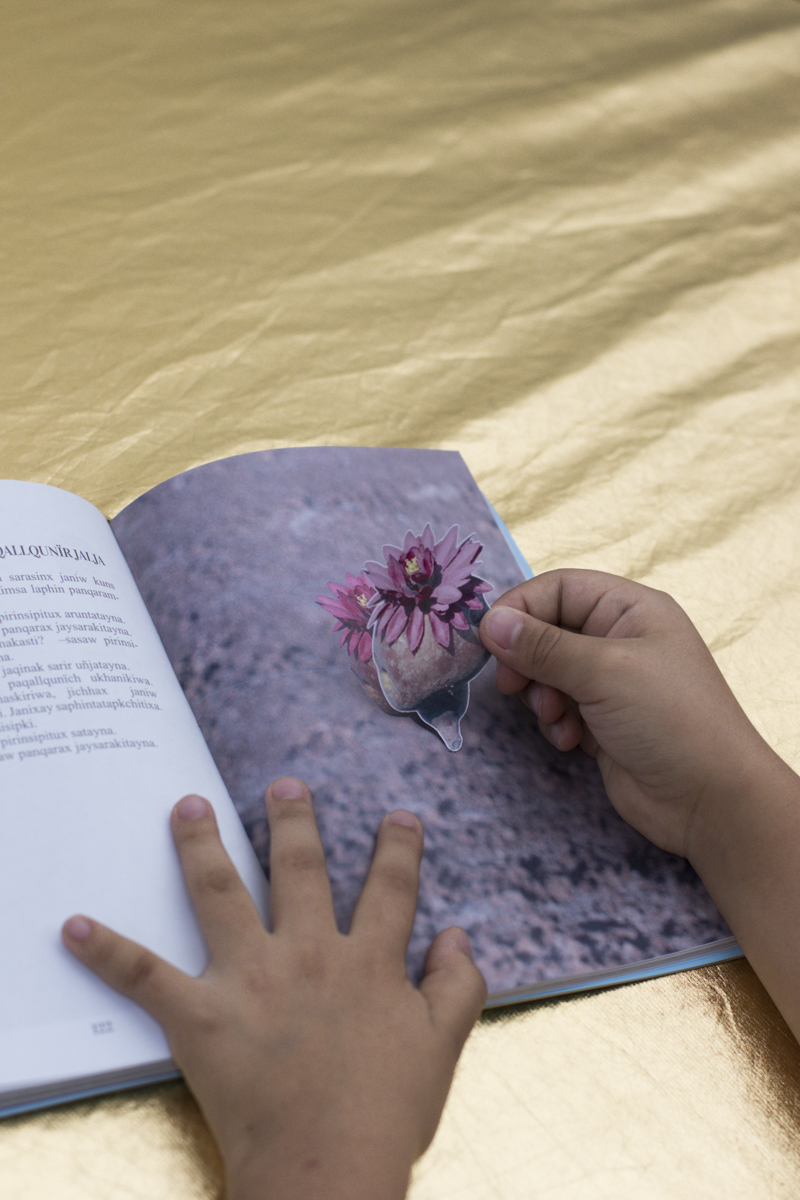

In the midst of this research to portray the heterogeneous, Warawar wawa was born. The Aymara term translates “son of the stars” and is the name that River decided to give to his book, where he explores how it would be a Bolivian Little Prince. It did so supported by a grant from the Bolivian State in 2019, in collaboration with Ruben Hilari Quispe and Martin Canaviri Mamani, who were in charge of translating Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s text into Aymara for the first time. Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo edited the project.

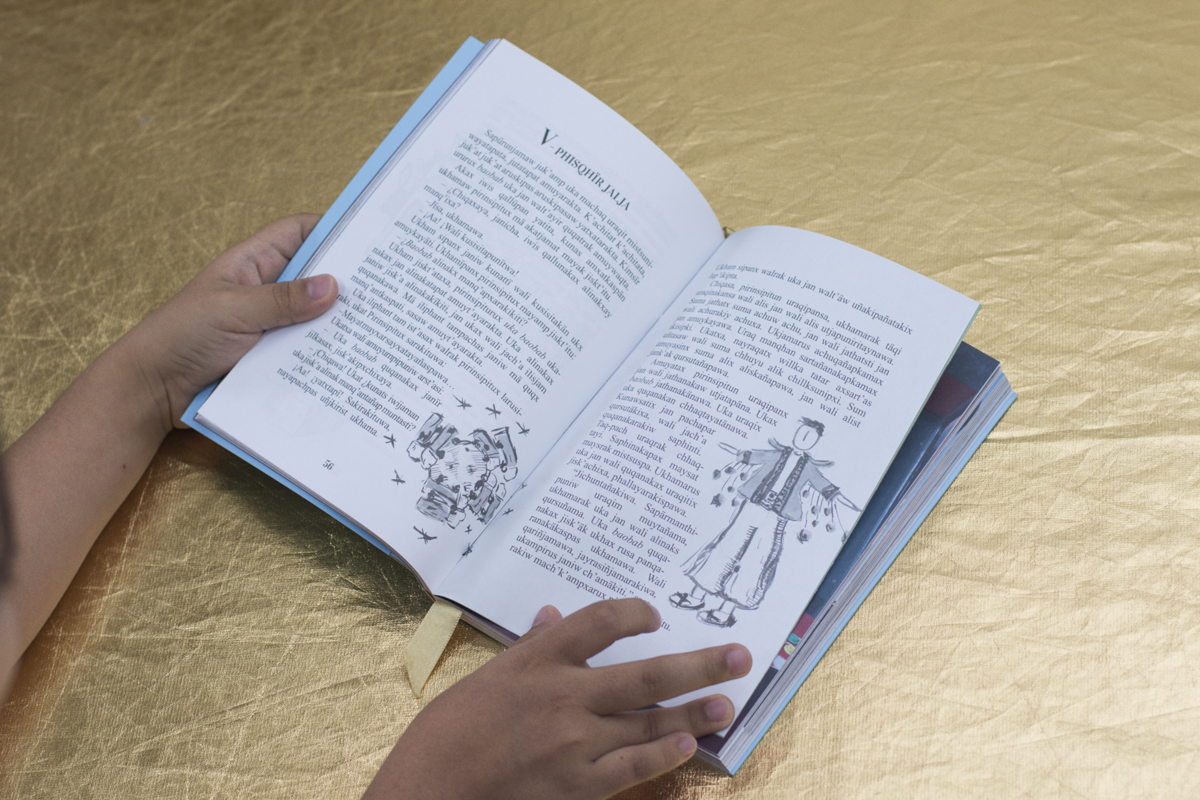

With the Bolivians Andes, El Alto, the Isla del sol, Uyuni, the Titicaca lake or the Red lagoon deserts in the background, River took the photos that he previously imagined and drew. As in the original Little Prince the sketches now accompany and illustrate the text of the book

This is how he imagined and then portrayed a woman buried up to the neck representing the Virgen del Cerro, patron saint of miners. To another one loaded with a lot of objects and turned into an ekeko, changing the gender of the popular figure, an abundance and fertility symbol. Also to a Yatiri —an Aymara traditional doctor— dressed in his traditional clothes and greeting the sun from his virtual reality glasses. And to a boy who explores the Bolivian mountains, wearing a Barcelona’s team t-shirt and a piece of a white tulle around his neck.

Along with the Aymara text and illustrations are images that range from bull horns in reference to virility to wrestling women with roses in their traditional braids. The work has multiple layers of reading: the poetic and certain lovely humor —as the humor that you can have with a grandmother who is loved— are only the first possibility of reading. The parellels between the Sahara desert and the salar de Uyuni in Potosi are the entrance to this mix of senses.

Anyone who is familiar with the Andean culture and has read The Little Prince will find other meanings: the bread shaped like a broken airplane over the ground of the salar is a tanta wawa, a bread prepared every November 2nd, honoring the souls that come from visit. River had to work a lot to convince the traditionals female bakers accustomed to make human figures and stairs, to make such bread. He needed it, of course, to build his new world.

– What do you think about the distance between “the Bolivian” and the representation that we usually access?

I always say: “the country is just a handful of images of belonging”. It makes me think that the homeland is what we imagine of it. In this sense, Bolivia has always been ruled by very colonial codes: People who came, saw us and took the exotic, for example a llama, a poncho or coca. What the Bolivian, even the creator of images here, has done is suck the finger that points us telling what we are and what we are not. My work, I believe, aims to challenge those imaginaries that seem obsolete to me.

-However, this is a look that stills exist, right?

If I show the photos I take to my grandmother, she would ask me to remove the virtual reality lenses to make it more “pure”. There is a idea of purity that is interpreted as “denying” the mark of the West. In the political speeches over the last decades in Bolivia it has been polarized in unpredictable ways the idea of “this is the indigenous” and “this is the stranger or urban”. That is why I consider that my project has a political character. Sartre spoke of “the political capacity of fiction “, of having the capacity to imagine other worlds. If we cannot imagine it, is very difficult to change it. This is what I think about in my work.

-Is there, in Bolivia, a previous tradition of that look?

From the photography I could say (and maybe it would sound pretentious) that it is not a common place to look at these indetermined identities; but from contemporary Bolivian art, it is. At this moment the contemporary Bolivian art has a lot of lights of young people like Marisol Méndez o Aldair Montaño working very well, and other contemporary artists like Gastón Ugalde, José Ballivián, Iván Cáceres… Also many sociologists and anthropologists speak of the Bolivian imagination that has always been in a constant crisis because this is a pluricultural/multicultural country and also because of the modern history of wars and territorial loss. This new batch of contemporary Bolivian artists is doing something interesting with all this history and my work is a result of that.

– How was this work born?

When I was studying I saw an African photo, who had a lot of combinations of foreign and own codes. This was impressive because it has to do with this black identity crisis. I found myself reading The Little Prince on the subway and when I read it for the first time I started to dream transgressively, I asked myself things like: “What would an African Little Prince be like?”. Then it was: “why do I have to talk about Africa?” There, the idea of a Bolivian, from the Andes, Little Prince was born.

-How was the process?

I was conceptualizing for about four months; then another four months of production and another four months of editing and setting the book, which has already been printed. All photos were taken with a team traveling around the Bolivians Andes. We made two trips, one for investigation and another for production.

-How did you find out the main characters?

In the first trip we launched a casting of many of the characters, we didn’t find all of them at that moment but most of them we did. In that process there were many “no” and many “why?” The man with the virtual glasses, for example. I didn’t know him but this photo was taken after we took pictures at La Puerta del Sol. He was around there and was curious, so we started talking and after a couple of hours later he was ready. He had a lot of fun, my processes are very collaborative, I like that the person understands why we do the things we do, we talk a lot. I have very beautiful photos of him, I asked him to imagine that he was interacting with the Inti, I told him “shake your hands with the sun” and he reacted as I expected: he raised his hands towards the sky. This process makes the photos much richer and it becomes more natural, more organic.

– To what extent did you planned that the result “resemble” the original Little Prince?

There is a magic, a feeling you have of “I don’t know if this photo makes reference to this character or I imagine it”. We planned something new but the original bookhat does give guidelines. I saw all the illustrations in the original book and I drew the photos long before I made them. In fact, the sketches do refer to specific things but we leave them on the air, without a caption so they can play in their own universe.