Photographer Angélica Dass was born in Brazil, the last country in the world to formally abolish slavery. From a young age she was exposed to racism in different ways. In 280 chibatadas –in english: whiplashes– she brought that vital experience to the field of creation. She worked on her family album –the daily record of a life full of domestic rituals, vacations, friends– and combined them with a selection of racist tweets that she compiled herself searching for key words and phrases on the social network.

Tweets and images dialogue by opposition and when they overlap they take the viewer from the memory of a full and happy childhood to the awareness of what she calls “wild banalities and a dehumanizing fatality of the other”.

—How do images communicate with tweets?

—I think tweets are there to show what isn’t in the picture. Although Brazil is celebrated as that multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, and even a multi-racial, word I don’t like, paradise. It is a lying narrative. Those who were enslaved in the 19th century continued to be servants of the 20th century and had fewer opportunities. The need to keep them dehumanized, in a lower human category, has been part of the history of this country. We are a colonialist, classist country. We are a country where one part of the population is considered less human than the other.

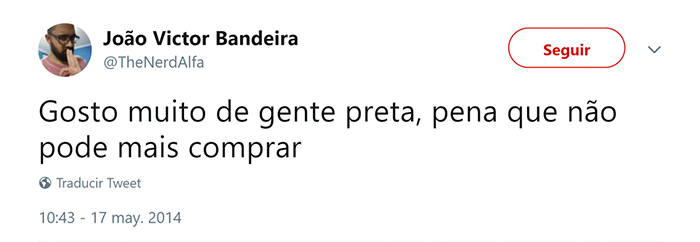

it’s a shame you can’t buy it anymore”

—How do racial stereotypes impact people’s daily lives and people’s wishes and dreams?

—Stereotypes are limiting. If you relate only on the basis of stereotypes, you are not really knowing who the person on the other side is because you have a whole imagination about who he or she is. People who relate to me do not do so with me, but with an image that they have crystallized about what I should be. That relationship already begins in an unequal and unfair way. All the time I look at the stereotypical way in which they represent me and many times I end up believing it is real.

—Somehow they get inside people.

—One of the tweets says, “I like black people, I just don’t like them to get engaged or get married.” At that point you stop to think that this stereotype was also a reality throughout my life. Stereotypes from a young age have taught me that I was not smart, beautiful or interesting enough. Those stereotyped images are limiting because they classify a group of people in a single act, a single activity, a single way of existing on this planet.

—When did you realize that the color of your skin mattered?

—I knew it from a young age, but you learn to protect yourself and live with it. It is not just my story, it is an expanding narrative. The role of women in society can be a very clear parallel: we have defined roles and the way you have to behave, the things you have to be good at and the things you can do and those you cannot. Throughout my life I have always faced that the image that others have of me comes before me. When I came to Spain I discovered that this daily violence to which I was accustomed was different, because I was in another country.

—In what way was it different?

—Living in an environment of discrimination, racism and oppression is like living next to a garbage dump. When you are living next to a garbage dump, the first days the smell is horrible, but after a while you don’t feel the smell anymore because the brain disconnects from that so you can survive. I was used, in one way or another, to live in the face of that violence every day. And at a one point the brain was disconnected from that, because if not I could not even go out to the door of my house. But when I went out and my house started to be on the other side of the planet, on another continent, I began to see that smells were different because narratives and dynamics were different. I am not saying there is no discrimination. I’m saying it is different.

—How do you find racist tweets? What’s your method? What words express racism?

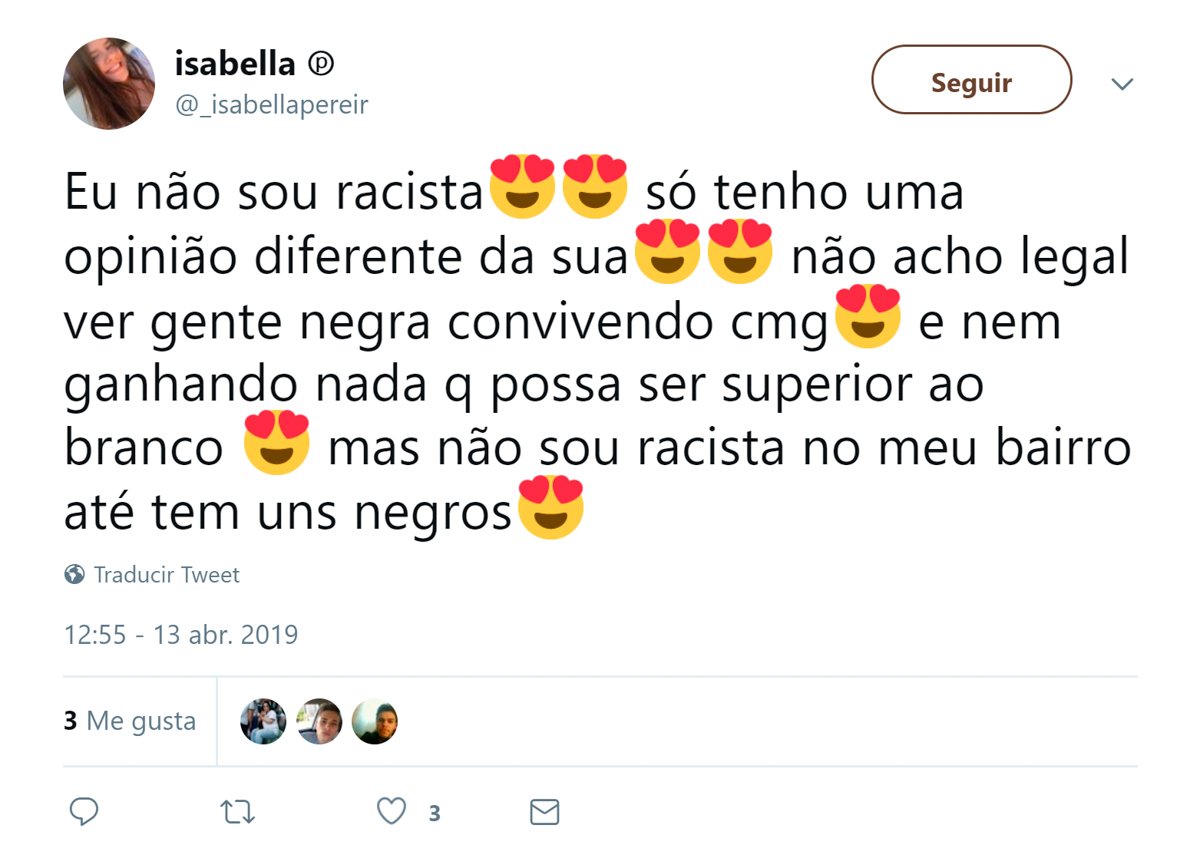

—What I did was look for these words in Portuguese: “I am not a racist but …” and there the person releases a prejudice that sometimes seems so absurd, like a joke. I also looked up the words “black,” “housemaid” along with some offensive language. There are ugly sentences, with people with very clear racist speeches, but what I was looking for was daily violence, double-meaning words. The last tweet in the entire series is from a person who says, “Making racist jokes doesn’t make you racist.” I chose it for closing as a questioning about those things that are part of everyday life: those phrases like “black with a white soul”, “you are dark but beautiful”. Those are not compliments, not jokes, those are racism.

—Is there a “typical profile” of a racist tweeter?

—Many of the people who wrote those tweets are very young, they are not older men than you can say “what a fascist this old man is”. The interesting thing about using twitter is seeing what kind of speeches we are keeping alive in this generation. Something is wrong if that things that were in force in 1888 remain so solid. That’s the point: how can we change that narrative, how can we make these young people empathize and understand that these messages are directed at girls like those in the photos in my family album. That album has the same scenes that they have on their albums, even if the girl that’s there is brown.

—Hate messages were already in the world before you were born. Forty-one years later, what changed in Brazil? What remains the same?

—The years of leftist government in Brazil have made it possible for many people who were never going to access education to do so. And being an activist, thinking about the situation of discrimination, is only possible when you have your basic needs covered. That is what happened to the Brazilian Afro-descendant population. With more access to education, they had the opportunity to propose this type of reflection, to understand where we have come from.

—And now, in Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil?

—Today, Brazil is very bipolar, with those two extremes where one part of the population sees the other as less human. Today’s newspaper headlines say the epidemic is under control because the upper class is not suffering from it. And a good part of the essential workers and those who cannot stop working today are people of African descent. We continue with the same dynamic: those who were slaves until 1888 continued in the same position of servitude in the 20th century, with exceptions that were wonderful and that have led to transformations.