A river in my backyard

In 2015, Brazilian photographer Maurício Pokemon arrived in Boa Esperança, a community of urban peasants protesting against an urban development project that threatened their territory. Pokemon accompanied that struggle, lived with the people, and initiated the Inventário Verde da Boa Esperança project: an exhibition and a photobook that collects small narratives of life and resistance.

By Marcela Vallejo

In the middle of the book, there is a map. On it, there is another map. Both are superimposed. The one in the background is the official one, made by the prefecture of Teresina: in the middle and blue is the Paranaíba River, and on it begins the neighboring state of Maranhão. In front of the green bank is the courtyard of the houses on Boa Esperança Avenue. Then there is the avenue, the road leading to the city’s most touristic places, leading, among other sites, to the mouth of the Poti River.

The other, the one that is superimposed, is an affective map: it is drawn by hand on a paper that is a little transparent. On the blue river, there are canoes with people smiling and others fishing. On the bank below are trees with fruit, houses in the middle of the green, and small mirrors of water in the flood zone. The first has red lines marking specific areas and borders between places. The second has stories of childhood, neighbors, and community.

The two maps are central to the photobook Inventário Verde da Boa Esperança by Brazilian photographer Maurício Pokemon. The book comes packaged in an envelope. Divided in two, from the contrasting cover images, each side of the book opens in an accordion, allowing you to play with the images you encounter each time the reader changes pages. “For me, the inventory is where images need to relate to each other. I didn’t think of a hierarchy of images but of a format that would allow them to be in dialogue.”

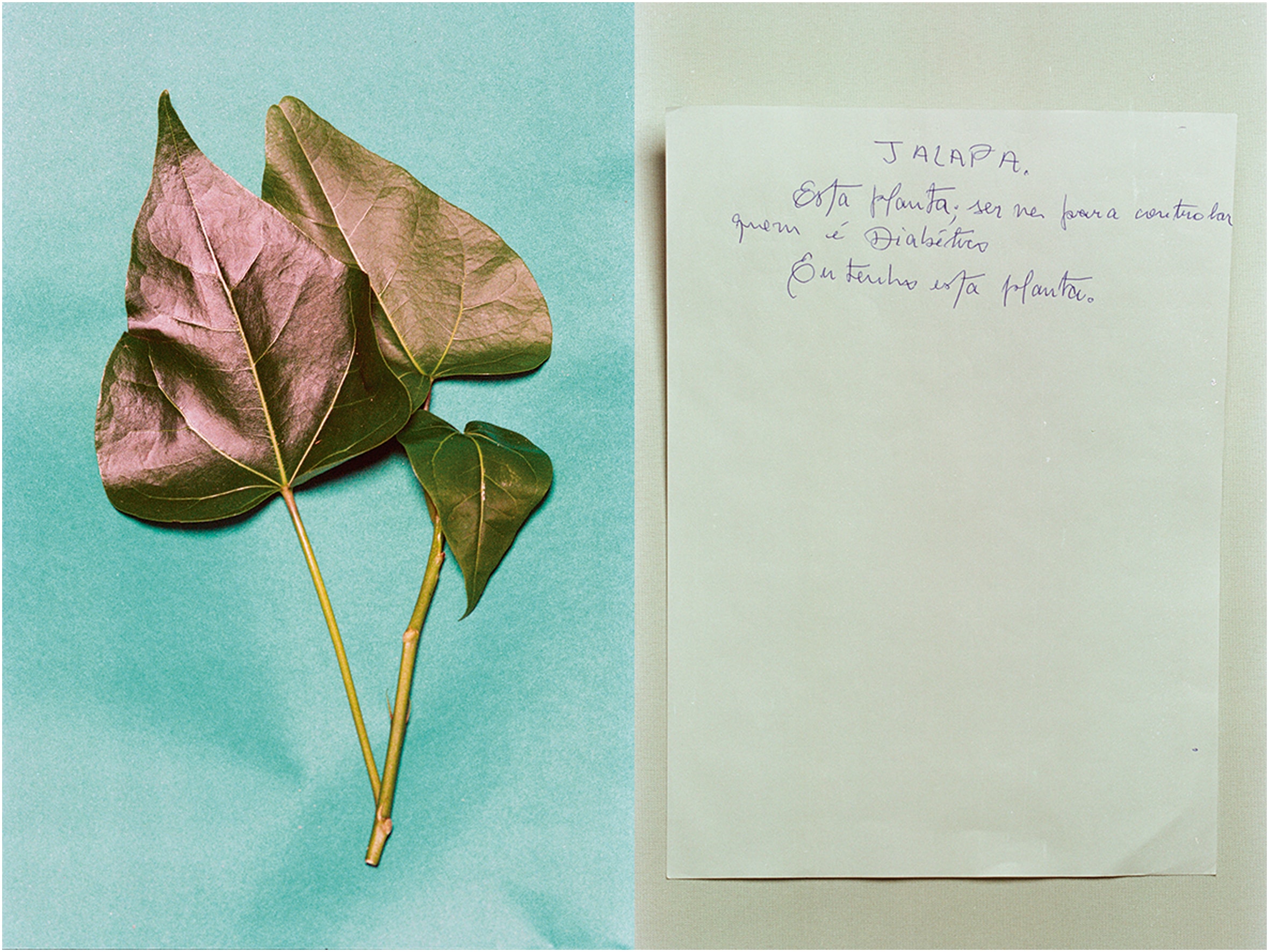

There are photographs, and there are small texts that evoke images. Arriving at the center is the map, the most common metaphor for talking about territory and yet the most incomplete. The Inventário is just what expands that notion of the map; probably that is why the map is the “last” thing to be found, and the map of affections is the first to be seen. The images that precede it are full of stories of everyday life: the hand that harvests the beans, the most common fish that fishermen catch, the agricultural tools that are taken to the Corona del Río, the characters that come out to play in the carnival every year, the ceramic pieces that artisans make.

Maurício Pokemon got to know the Boa Esperança community in 2015. The area was part of the everyday landscape of his life, but that year he saw something that caught his attention. On the houses, there were graffitis with phrases of protest and criticism. Such as “The history of Boa Esperança is its dwellers,” “Housing is a right. We demand to live, fight and resist,” “Mayor, Boa Esperança Avenue is not yours. Respect,” and “TV green city. The mayor’s good image.” The power of what was said there led him to have his first contact with the community.

That is how he learned that the Prefecture intended to develop Lagoas do Norte, an urban renewal project to widen the avenue and build a luxury tourist complex. The residents insist that Firmino Filho, the mayor at the time (still in power), was trying to take away their place in the city, to uproot them and thus expropriate their memories and affections.

The city started there. According to the official narrative, there is a place called ground zero, where the town was founded, and the first houses were built. The people of Boa Esperança say that Teresina began where they now have their home. They are primarily people of African descent who live in the city but retain rural rhythms and ways, i.e., urban peasants. The houses face the river, which means that the river is an extension of the land for the inhabitants.

The Prefecture project concerns conserving and protecting the fauna and flora on the river bank, but this does not require a large urban development project. The people, throughout their history, have done it. They are farmers, fishermen, and artisans who have built a particular territoriality in which they move with the river’s rhythms and floods on their islands.

When he met them, Maurício proposed an idea that became the Existencia project, composed of full-body portraits of the neighbors. “Thinking people as trees in their backyards, as being rooted in the territory and part of the place.” The photos were printed life-size and pasted on the walls of the city. That got the press interested, and the community received a different kind of attention.

A few years later, he received the news that he had won a scholarship for which he had applied in 2012. It was a surprise because he didn’t count on it six years later. But it was the kick-off to start something new. It was then when he proposed to the community to make the Inventário Verde da Boa Esperança, together they decided, knowing that they would do it with money coming from the Prefecture itself.

“I wanted to do some analog photography. It made a lot of sense to me to think about another time of images with this project,” says Pokemon. “I was interested in doing something that would convey more of that permanence in memory.” At first, he sought to make a collection of images with green as a theme and motif, but that quickly petered out.

With financial support, he proposed a residency at Campo, a space to exhibit and reflect on contemporary art in Teresina. They launched a call to think together with other Brazilian artists around the territory and everyday life. Everything that they discussed there gave a new air to the Inventário project. So Maurício started a series of meetings with the neighbors to decide what should be in the inventory.

“The Inventário was much more a portrait of life, all based on closeness and coexistence. The intimacy was much greater; there was more trust, and people in the community knew my work. We were able to make images of life happening”. Mauricio went to Boa Esperança every day, early in the morning and the evening. He captured the lights that accompany the life of that community every day.

The strength of the relationship meant that people who could not stand cameras and photographs later called him to photograph what they considered important in their lives; this happened with Mr. Valdir. Maurício had been visiting him for several years, and they liked to sit and talk; that’s how he knew Mr. Valdir didn’t want photos. He said that other people had already gone to photograph him, but he had never seen those images; he didn’t know what had happened to them.

One day Mr. Valdir invited him to the Corona del Río; it would be a day of agriculture. Once there, he asked Maurício to take pictures of his workplace. He wanted to put those pictures in his house so that visitors would know the “land so green, so beautiful, with a lot of beans of different types” that he worked. “Mr. Valdir has all that wisdom about beans; he knows which is the 30-day bean, which is the 45-day bean”. It was there when Mr. Valdir appreciated the images and realized his work’s importance. After that, he invited Maurício to take pictures of his family and himself.

Mr. Valdir was one of the people who went to the project’s exhibition in Campo, the place of art, and there he talked about the importance of their agricultural work and what they have done and are doing for the city. “That gave me a notion of how small this work is,” assures the photographer, “and I like that because that makes it close to the people. It’s a small project and a small book, as it had to be.”

The book was printed using the risograph technique, giving the images a particular texture. It is handcrafted and well-made. It may seem delicate, but it is more vital than it looks. The images and some texts are little narratives of people who, in their daily lives of agriculture, crafts, and domestic life, make life and sustain a way of making the world that seems to go against the seemingly inexorable flow of progress.