Ancient beings take my dreams

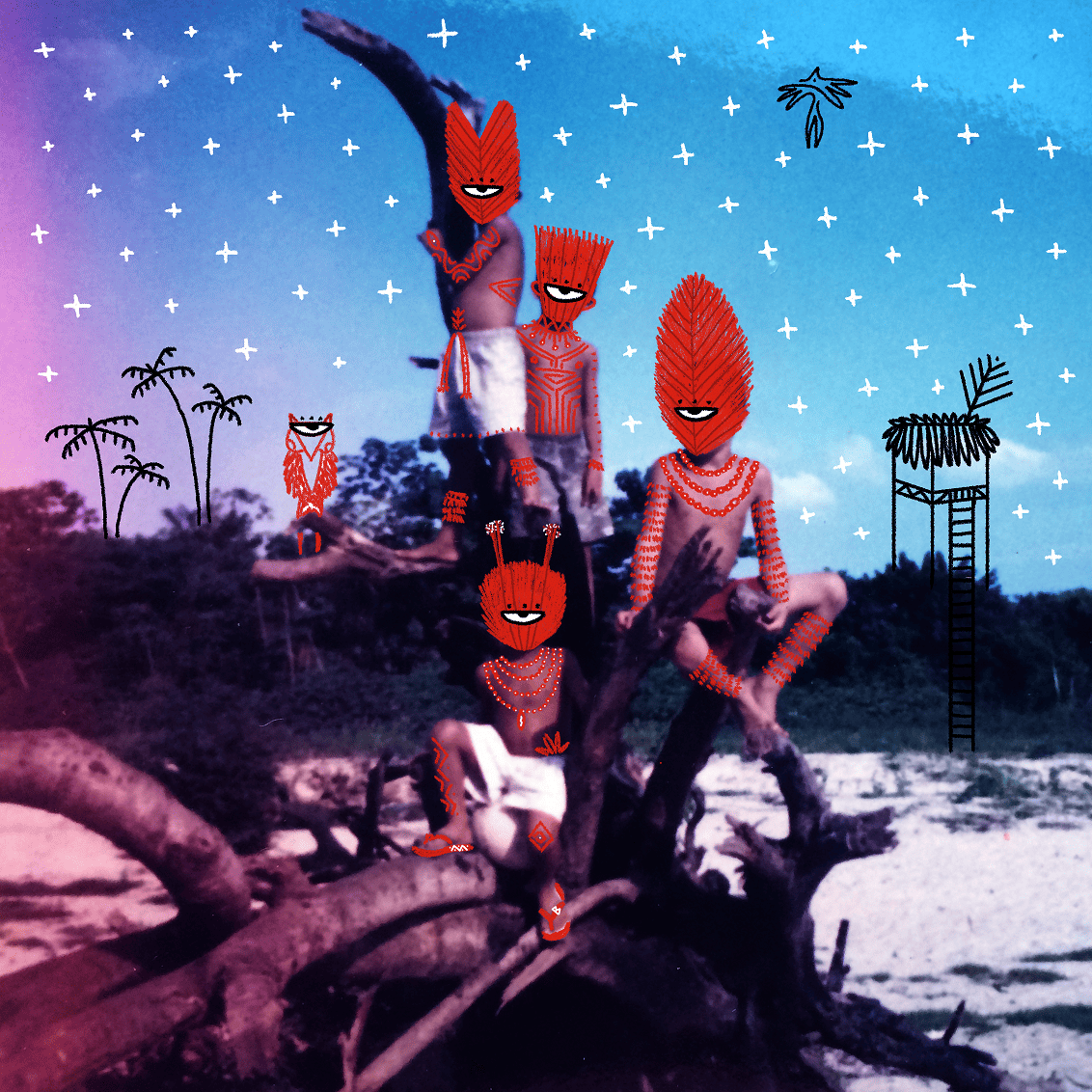

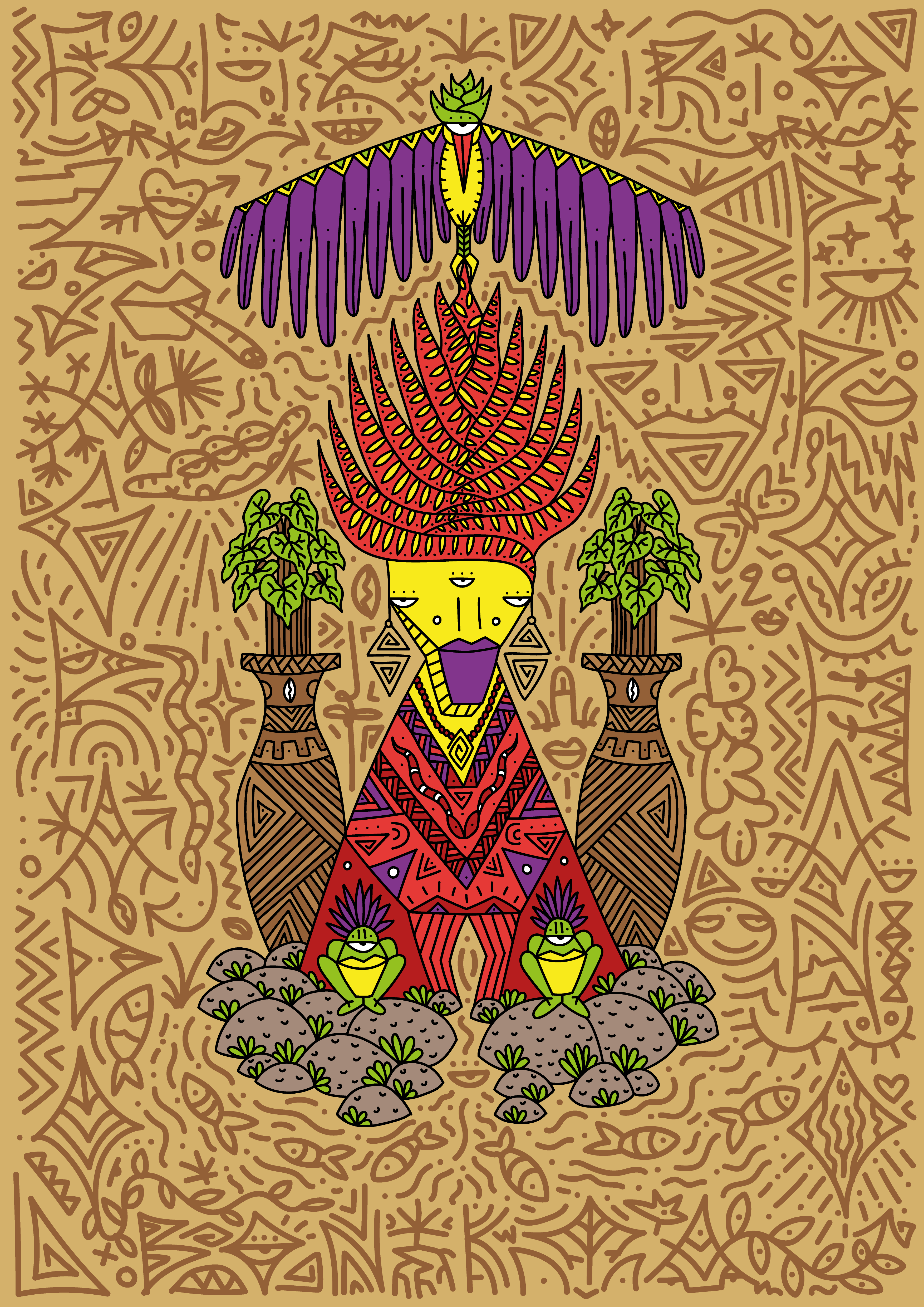

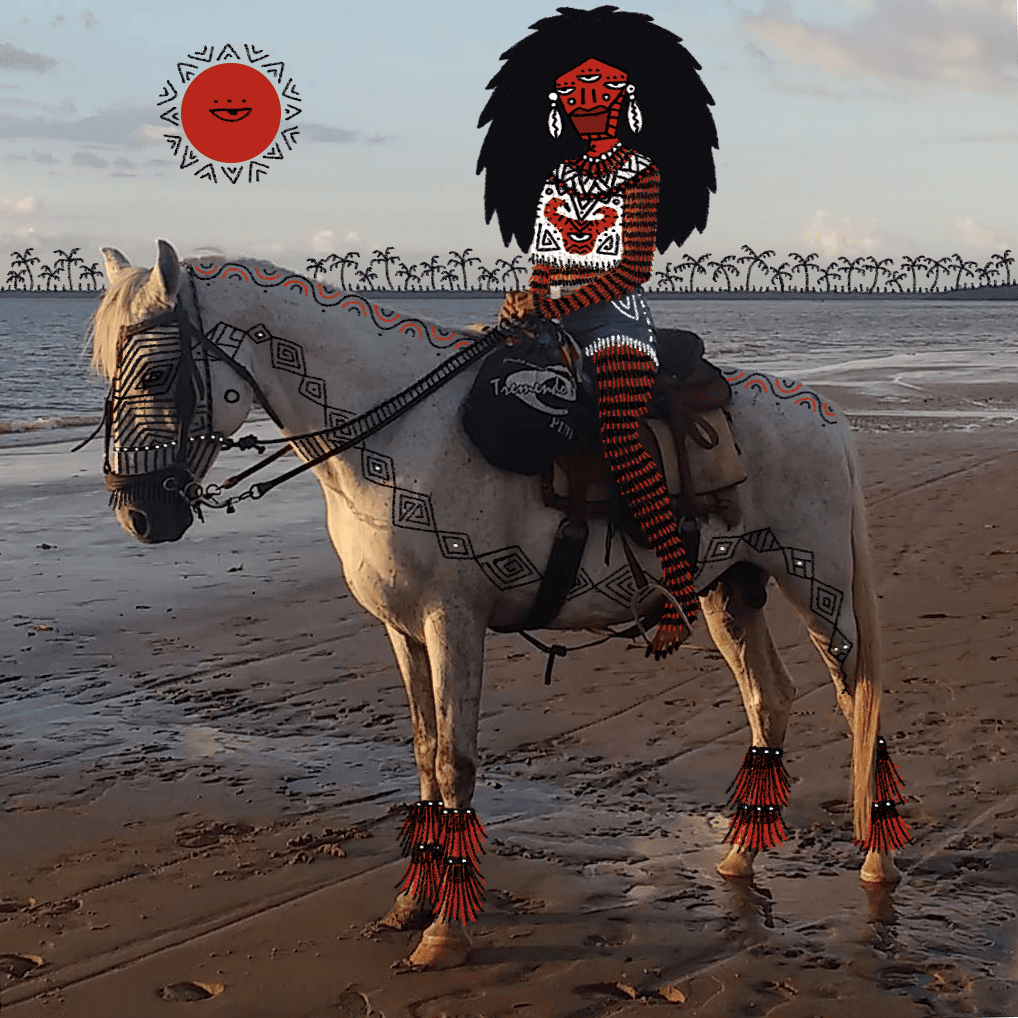

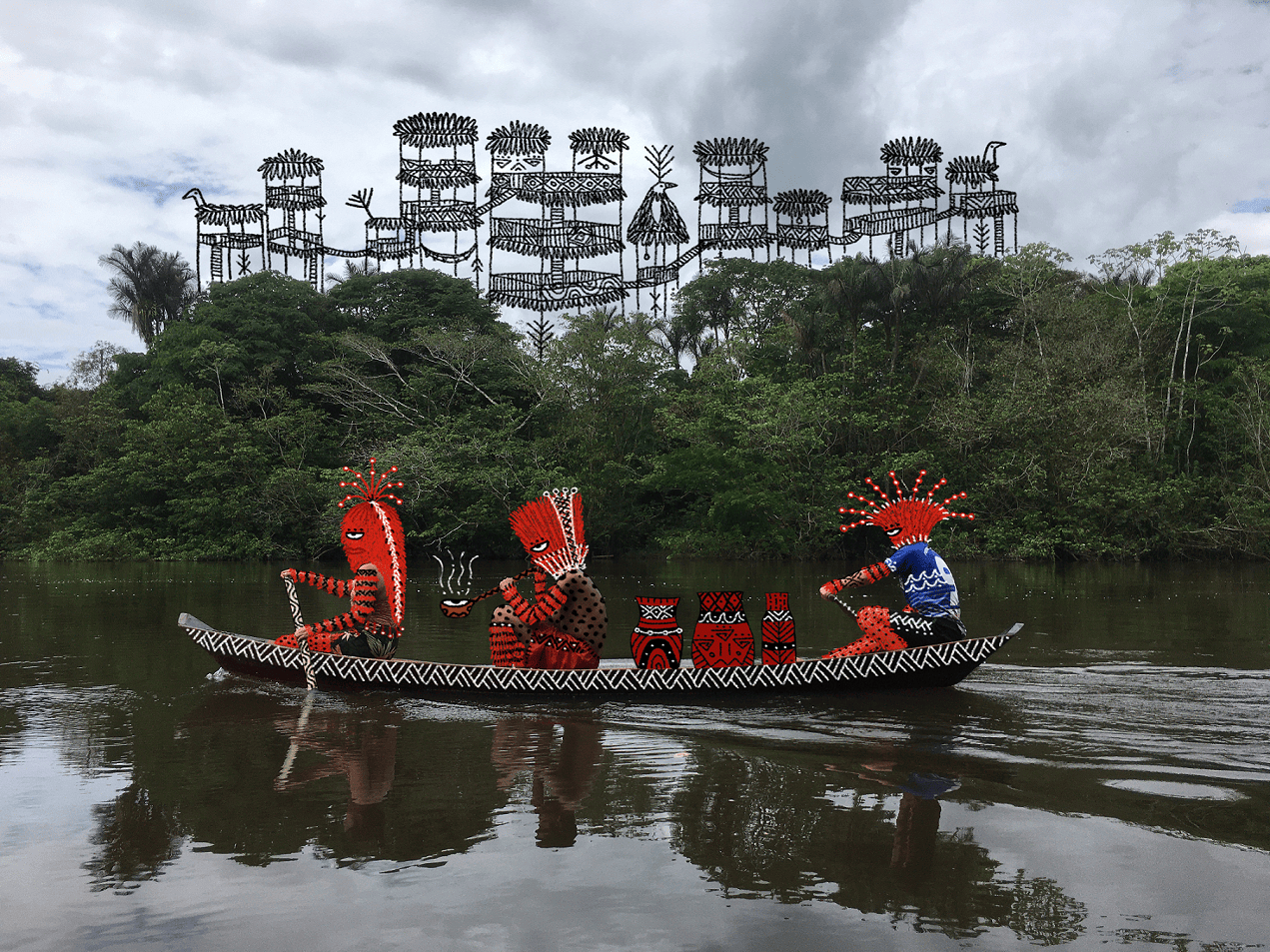

Bonikta, the artist Caio Aguiar, exhibited her works at the 2023 Amazon Biennial in Belém do Pará. Her pieces blend many techniques she has worked with throughout her career: photo collage, drawing, pixos, graffiti, and wallpaper. Her works feature Marajoara indigenous graphics and enchanted beings that are part of his daily life and spirituality.

By Marcela Vallejo

A creature that becomes a person, people who become creature. That is Bonikta’s motto, the name by which Caio Aguiar is known in the Brazilian art world. Bonikta discovered herself as an artist when she moved to Belém do Pará from a small town called Ourem in the interior of Pará.

The city welcomed her with violence but also with art. Seeing urban graphics, interventions in public spaces, colors, and shapes led her to discover her creative potential and explore her images. For Caio, the images he creates are already within him before they are brought to life. He says that a significant part of his creative process is dreams, as it is the space where he encounters his images.

He also knows that these images have been created throughout his life and the lives of others. Ancestry and spirituality are undoubtedly keywords when speaking with Bonikta. The images she creates come from the personal history her ancestors embodied, particularly in her great-grandmother, grandmother, and mother. They come from the baths in the rivers and igarapés of her homeland, the enchanted beings that inhabit them, and the calls Caio received since childhood.

“In the city, I lose myself, and in art, I find myself,” she says. In this city, which can be a great trap, Caio reactivated his knowledge as an inhabitant of the interior “to know where and how to step.” This marked the beginning of his artistic career, characterized by experimentation and a blending of techniques. Caio doesn’t like to talk so much about techniques because that would imply discussing materials and access, something few want to address since art struggles to completely shed its colonial covering.

However, Bonikta’s art incorporates photography, drawing, graffiti, pixos, indigenous graphics, wallpaper, collage, and tattoos. That challenges the traditional understanding of art, expanding the idea and concept, especially because it is they, a being who transforms into a person, a racialized body, an individual from the interior, who creates it.

“I see the city as a great trap, but where I come from, we know how and where to step, how to swim. It’s an unequal exchange: knowing how to use my ancestral knowledge in a place that tries to erase me. The city is a very violent place.”

What would it be if you were to think of a place of enunciation for your creations?

When I was finishing high school, I moved to Belém. I am from the interior of Pará, from a city called Ourem. I went to the city to access higher education levels and basic necessities like healthcare. When I arrived in Belém, I discovered that I could be a person who creates art. Urban interventions, graffiti, pixaçoes – things that didn’t exist in the interior – began to awaken the desire to express myself and the possibility of doing so.

So, I tend to create based on this journey. When I move from one place to another, I think of it like crossing a river without knowing exactly what I’ll find on the other side. At the same time, I know I’ll meet other people who also create art and will inspire me.

In the city, I started making interventions in the space with graffiti and wallpaper; this is how I encountered the arts in the city, but at the same time, I lost myself in terms of the person I was in the interior. In a way, the city makes me lose myself, and art helps me find myself. It’s in art that I discover who I am.

The city is very stimulating but also challenging and harsh, especially for those coming from elsewhere.

I see the city as a great trap, but where I come from, we know how and where to step and how to swim. It’s an unequal exchange: knowing how to use my ancestral knowledge in a place that tries to erase me. The city is a very violent place.

Nevertheless, that’s where I’ve learned many things. Tattooing, for example, has been a survival tool. But it’s also a vital outlet because it involves marking people on their skin and requires a lot of energy, as it’s a bodily exchange. The people I tattoo carry my art on their bodies, and that’s how my art begins circulating in the city on people’s bodies.

Now that I’m well advanced in my university career, I’ve gained a deeper understanding of what I do. I’ve come to understand that everything I do exists within me, comes from my ancestors, and is connected to my spirituality. There are even things I don’t know how to talk about that remain a mystery because they don’t have a clear explanation.

How is it that your images come from your ancestry?

I was a very free-spirited child, a bit disobedient. My mom would say, “You can’t go to the river to bathe now; don’t go to the Igarapé today.” But I always went. And in those acts of disobedience, I managed to perceive the enchanted beings of the river. So, from a very young age, I feel this spirituality that runs through me.

When I started drawing, I began to understand that everything I experienced, and the calls I received when I was younger came to me through dreams. So, dreams are the place where I receive a lot of inspiration. Sometimes, I dream and spend the whole night drawing the dream, waking up tired. But the next day, I already knew what I would do and learned through dreaming.

But ancestry has always been there, from the teachings of my mom or grandmother, who taught me how to take baths, light candles, recognize the timing of rain and sunshine, and know when, how, and what to plant.

Some elements, such as specific strokes, colors, and shapes, recur in your works—for example, the eyes.

Yes, the eyes are something representative of what I do. Some people say that they already know it’s one of my works when they see those eyes. When I was a child, I had an eye infection and almost went blind. It probably has something to do with that, but it relates to vision and the symbolism of what eyes represent.

There are also the Marajoara-inspired graphics from one of the oldest peoples in this territory. It’s something that identifies with Pará. And it’s not just those graphics; I design others, and when I do, I think we all have those symbols within us.

“Through my art, I perceive that my ancestry exists, and that’s when I search for that history. That’s how I discovered that my great-grandmother came from an indigenous village. That’s when I realized that for me, the root, what’s in the ground, the trunk, what sustains me, is indigenous ancestry.”

Often, when we talk about ancestry, many people envision ethnic communities. We all have ancestors, but it’s experienced differently in Latin America, partly very much shaped by racial issues. How is it in your case?

Racial issues deeply affect me, even that mestizo identity, which is a big myth to me. The Europeans came, invaded, and called us “Pardos.” What’s that about “Pardos“?

It’s an erasure of identity to the extent that we don’t even consider it. While I lived in the interior, I never thought about race. It’s something recent; through my art, I perceive that my ancestry exists, and that’s when I search for that history. That’s how I discovered that my great-grandmother came from an indigenous village. That’s when I realized that the root, what’s in the ground, the trunk, what sustains me, is indigenous ancestry, despite the attempts to erase it.

Here in Brazil, there has been much discussion about reclaiming history, about people with indigenous ancestry trying to reclaim their identity somehow. It’s an intense discussion, as some people think only those living in villages are indigenous. But there are indigenous people in the peripheries of cities, in the interior of the country, people who were forced to deny their identity to work. And there is a lot of ignorance regarding this erasure.

Considering the importance of ancestry in your works, seen as a series of images within you that accompany you that appear in dreams, I would like to delve a bit into the works of the “Memorias Enkantadas” series. This series consists of photographs intervened with drawings. What are those “Encantados” (enchanted) that appear in these images?

These are some of my most recent works and are a great mix of everything I’ve done before. So, before I started drawing, I always liked taking pictures with my phone. Back then, I didn’t understand the process of photography as an artistic process. That happened later when I began combining photographs and drawings. It also includes some paper mache masks that involve performances.

In other words, there’s a mix of techniques. For me, it’s all about experimentation. Art, for me, is an experiment, and it’s never the same thing; it’s never something definitive. I don’t like idealizing or confining an idea to a single word. I don’t like to say that I am this or that.

This is also because the very concept of art is colonial. Many ancestral practices are still invisible, making a distinction between artifacts and handicrafts. So, within my artistic experiments, I am greatly inspired by water; Bonikta comes from the waters.

This series of photographs comes from my research called “Art and Memory.” The proposal is to rescue my memory through photography. Through the image, I can create a narrative infused with these “Encantados,” which exist for me in everything, even in the city. For example, I see the trees that still live in the city, the river that is nearly dying, and I see the “Encantados.” They are in everything: in people, in forests, in waters. It reveals itself to me, something I can see thanks to my sensitivity. Based on that, I decided to create a process of enchantment in the images.

Photography also appears in the series “Cuidado Donde se Sumerge, Nuestras Aguas son Encantadas, Cuidado” (Be careful where you immerse. Our waters are enchanted; be careful). But in this series, they are photo collages. What was the process of creating these pieces like?

Yes, it’s no longer a single photograph but several; they are fragments of memory that, when brought together, form a map. There, photography is a path.

The montages were done with wallpaper, a technique I used on the streets and brought into the exhibition space. It also includes Pixos and drawings. All the interventions with photo collages were done during the assembly process. I didn’t know exactly what I would do, but my vision was already trained. It had a specific direction. During the five days of assembly, I dreamt a lot; each day, I dreamt a different part of the work.

The central concept proposed by the Biennial is about water as a source of inspiration. So, I brought in this idea of “be careful where you immerse” to talk about respect and the care of asking for permission in sacred, enchanted waters.

I thought about what you said regarding the importance of territory, colonization, and how art is a colonial concept. It seems to me that to decolonize art, it’s necessary not only to expand the concept but also to discuss techniques, materials, and access.

The history of art is colonial. When I stop to think about my experience with art, I remember that in school, they used to say that art was about the Renaissance, which bores me. It’s fine if there are people who study that, and if that history is like a fetish. But that’s a history that erases me, erases dissonant bodies of race and gender. It’s an art that is created from bodies descended from a colonial, whitewashed, heterosexual male pattern.

The mere fact that I exist is a gesture against colonial thinking. But when creating art, it’s crucial to confront that, to take a fragment of that colonial history and re-create on top of it.

For me, decoloniality is about creating new narratives that are not violent, don’t tell the same story, and highlight different perspectives. When I think about creating art, I consider the image of my grandmother, mother, and friends. For me, that’s important because those stories won’t be told, so making art is also about telling stories that have been erased that won’t be in the books.