Aquelarre: design beyond design

Popayán is one of the oldest cities in Colombia. Among other things, it is known for its traditional Catholic celebration of Holy Week. In 2014, the mayor’s office issued a decree banning “profane-type spectacles” during that religious celebration, considering them disrespectful of tradition. Yes, this was happening in a secular country in the 21st century. Faced with this situation: Alexa Muñoz de la Hoz, Mónica Quevedo Hernandez, Natalia Fernandez Hormiga, and Olga Benavides, graphic design students t that moment, decided to join forces to create accessories, decorative elements, and other things with explicitly profane themes. They called this meeting Aquelarre.

Seven years have passed, and Aquelarre is still alive, now as a design laboratory, which will soon also be called feminist, like this: Aquelarre. Feminist design laboratory. The four of them have transformed in all these years: they graduated from university. They went from making accessories to creating, designing, and accompanying pedagogical processes associated with sex education, the gender approach, and feminist debates.

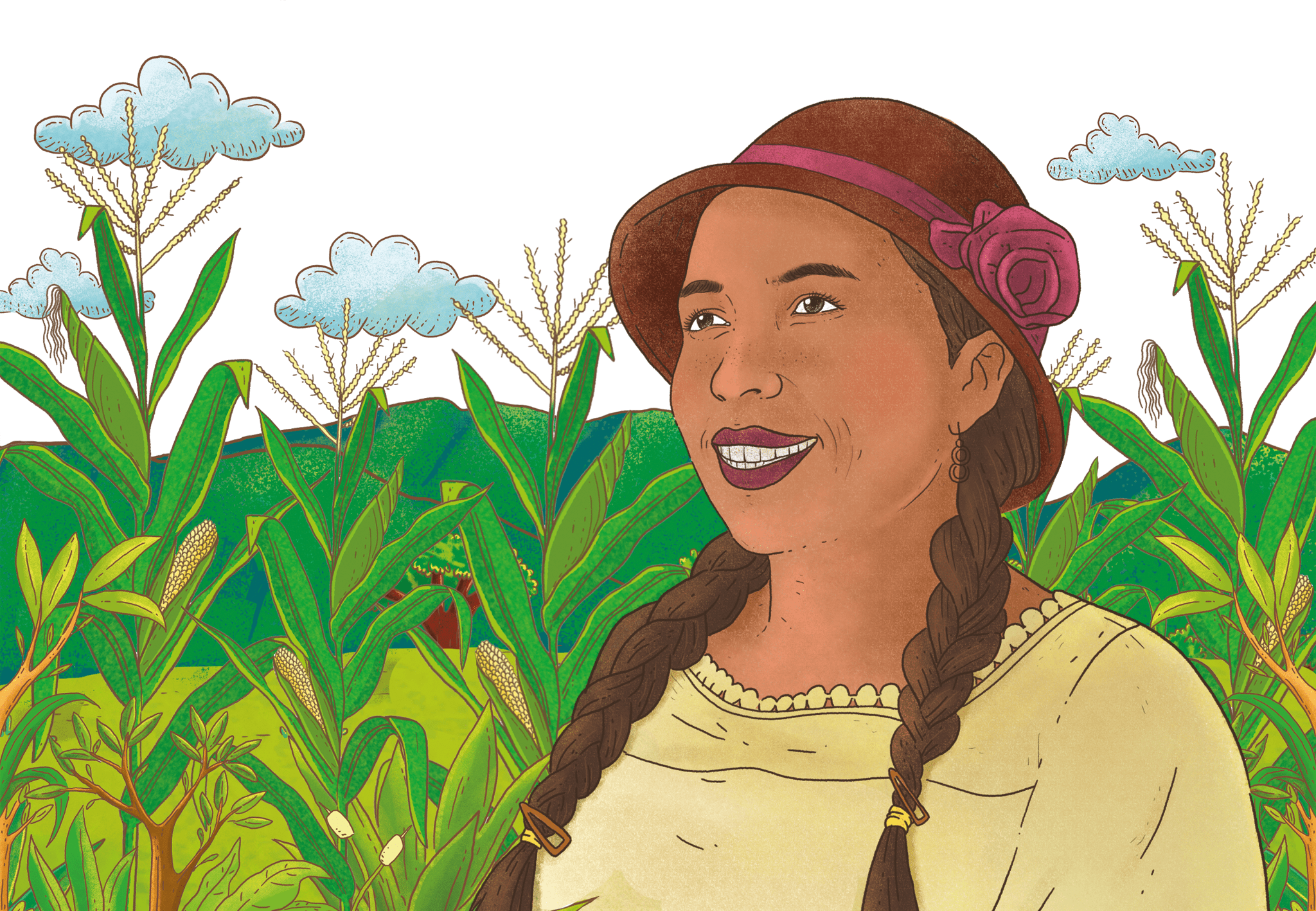

The witches of Aquelarre were the illustrators of all the pedagogical material that accompanies our project Imaginar el Fuego de la Memoria. Last week, we saw their illustrations displayed at the AECID Training Center in Cartagena. In this interview, they tell us a little about their trajectory.

You started working together in response to that 2014 ordinance in Popayán. At what point and how did you consolidate as a collective?

Olga: Two things happened: the first was that we began to build spaces for collective creation, both among ourselves and other people. So, for example, we held a short story contest which resulted in a publication called La Hora Muerta (The Dead Hour). The second thing is that we continued our academic training and began to relate to critical theory, especially feminism and gender. In that case, our first approach was with a project that already had a prototype, Anatomía de un Sujeto Andante (Anatomy of a walking subject). There we began to investigate the evolution of sexuality, playing with the format of the text.

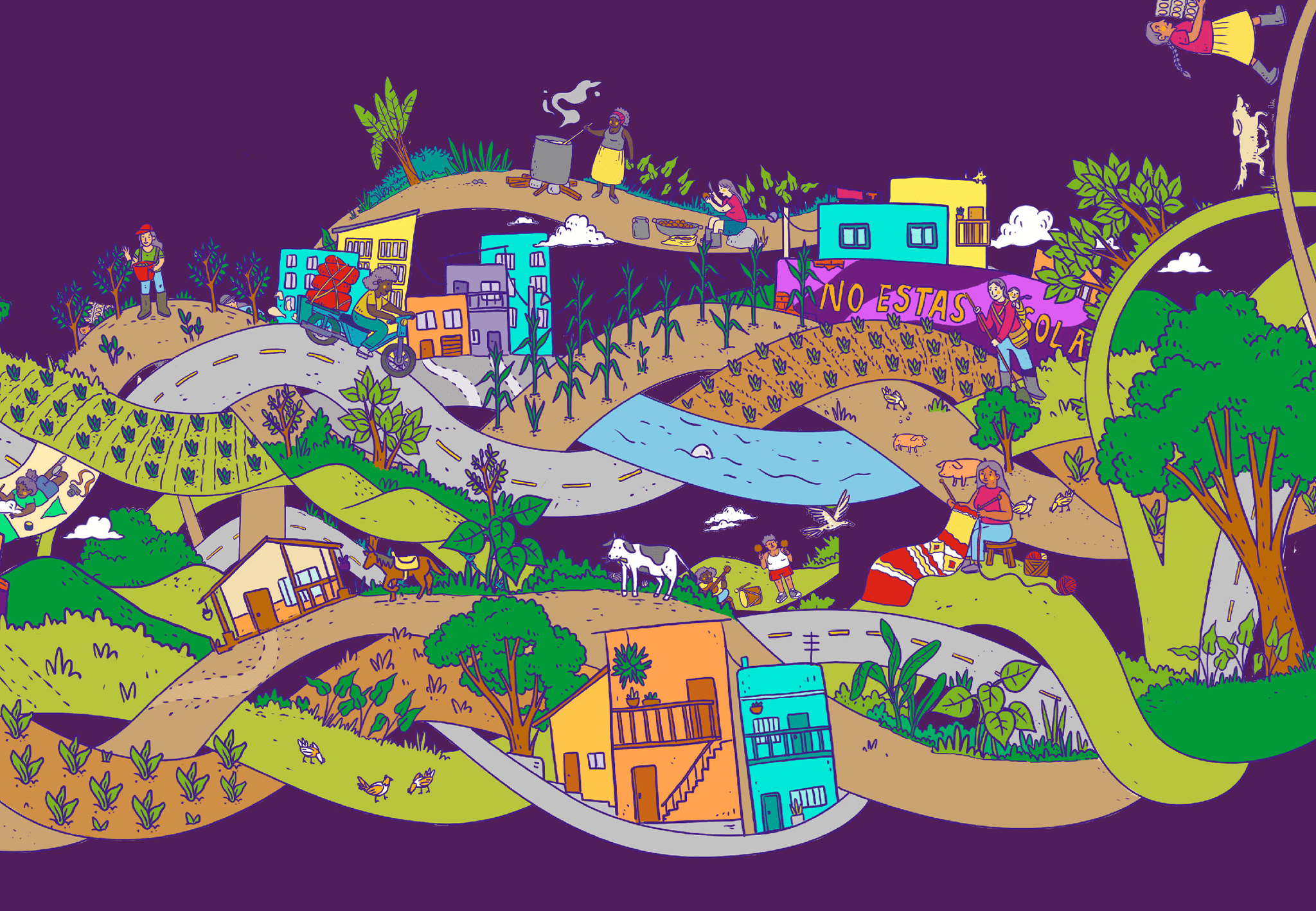

Nata: In addition, with Alexa, we had a project called Trans-figura, with sex workers from the Bolivar neighborhood, generating spaces for discussion and collaborative creation, seeking to vindicate their rights. We came from the student mobilization, and we had learned that design could be part of all the initiatives developed in the territory. We realized that design allowed us to plan and generate spaces with these projects. That is to say, not only thinking about the final piece, but with the whole process, we were able to dynamize something bigger and more powerful: a social process.

Alexa: We were doing all that and talking a lot, but we had not stopped to think that this could be Aquelarre. In 2017 we talked and realized that we had questions in common about certain things. Between the four of us, we did two-degree projects that coincide in that they are designs of educational materials to talk about gender and sexuality. Then we realized that this also had a political purpose for the four of us and that we had the skills to achieve it. There, we stopped the production of accessories related to witch stuff and decided to think about creating our design lab where we develop both our projects of educational materials and offer design services.

This political approach to design is fascinating. Arturo Escobar criticizes solely instrumental design in Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds and proposes to get out of that place to think about its autonomy and political potential.

Alexa: It is difficult to leave that place because design history is associated with industrialization processes and capitalism. But I believe that our political commitment to generate content allows us to create other ways of relating to creative approaches. For example, when we are called to work, we try to have critical voices within our projects, and we propose ourselves as part of the teams. We don’t think of people as clients unless they are very technical assignments. We think of these people as accomplices or allies in the process of creation and research.

Mónica: In this sense, it is important to say where we come from; Unicauca proposes a design that thinks about the context and recognizes that we are in an especific social place, in this case, in Cauca. These are essential questions for us: what is the role of design in society? And what are we contributing from there? We call ourselves a laboratory because Aquelarre is a space for joint creation and experimentation. We not only materialize ideas with others but also continue working on our projects that respond to questions that cross us as women.

The idea of collaborative creation is often repeated. Is that the approach?

Natalia: For us, it is essential because we understand that what we do is not done by the four of us alone. We weave crucial networks. That is why we consider that interdisciplinarity and dialogue are essential concepts for building. We are aware of the limits of our discipline, but we believe that they are not a disadvantage but a possibility to work with others.

Why the emphasis on pedagogical processes?

Natalia: The student mobilization of 2011 was significant for me because that’s when I understood that design was not only what I was thinking at the time. I realized its full communicative and political potential. That’s when I understood the importance of education. We are also the daughters of teachers, and in our homes, the discourse is that if we educate ourselves, we can move forward and mobilize.

In that mobilization, the struggle was so that people like us could study, people who, without the public university, would not have been able to learn. With education, we can transform reality.

We believe it is vital to create elements that allow us to learn, doubt, debate, and dialogue, which can be done through pedagogy.

Olga: Education also brings us closer to a critical view of the world. Thus we could realize that the world is not still but that there are truths positioned through discourses of power, established through hegemonic forces that have the tools to stay in that place. I feel recognized with the learning processes by understanding that between learning and narrative, I manage to reach exercises of doubt, and thus we can generate methods of resistance.

Why did you choose illustration?

Natalia: we feel that with illustration, we can build other worlds. In drawings, everything is possible.

Alexa: We have learned to illustrate together. We are not interested in saying that this book is Olga’s and this one is Monica’s, but that there is a sense of collective ownership. Illustration has also provided us with a tool for co-creation. And at this moment, we are recognized for doing illustrations and talking about specific topics.

Monica: Illustration is something that moves, that awakens emotions, and leaves behind the idea of realism that other types of image creation can have.

Soon the name will be Laboratorio de diseño feminista (Feminist Design Lab). What does this imply?

Nata: I think it is a political stance. It is like a new layer that arrives. Let’s say one grows in layers like the earth. Now we are much more conscious and focused on the search to work from that perspective. We want to think of ourselves from a feminist perspective. And that will determine the way we approach the research, the sources, the information, the techniques, and the formats.

Alexa: But it also helps us think about our practices among ourselves since we are not only colleagues but also friends. That is where feminism has materialized. When we decide what we will bet on, we ask ourselves what is going on in our lives. Working in Aquelarre is personal work. We know each other in many ways, which makes us prioritize care without romanticizing.

Olga: Feminism is a transversal exercise. It puts us in the dynamic of relating to each other from the idea that the people we interact with have good views of the world. It implies an exercise of active listening to ourselves and to the people with whom we do projects. In other words, it is linked to the ways of working and the responsibility of complying with the agreements we have made.