Art and drugs in Colombia: an investigation

Rodrigo Lara Bonilla was killed, arriving at his home on April 30, 1984. Pablo Escobar hired the hitman. Bonilla was Minister of Justice, and one of his flags was the fight against the Medellín cartel. After his death, the government of Belisario Betancur approved the Extradition Law, which officially began the so-called “war on drugs” in Colombia.

Researcher and curator Santiago Rueda remember the night of the assassination. His house was near the place where it happened, and he remembers the impact he felt, not only because of the event but also when he saw the hitman, a boy a little younger than him. That day, Santiago says, Colombia became a narco country. “That marked a before and after. From that point, the number of anecdotes that all of us Colombians have about the narco is endless.”

Santiago studied arts and began to work on the issue of drugs and the narco phenomenon in a more visible way. Starting in 2008, when he published his book Una línea de polvo. Arte y drogas en in Colombia. At that point, Santiago had identified a series of works that dealt with the subject in journalism, film, and literature. But there is a void in the study of the visual arts. Thus, he began a series of investigations that he later extended to the rest of the continent, accompanied by exhibitions in several Latin American countries.

In Una línea de polvo you decided to use the expression “el fenómeno narco” and not the word “narco-trafficking”, why did you make that decision?

It is not my idea. Narco is not only trafficking. Colombia is a producer, marketer, launderer, and consumer country. Additionally, we have a tradition in the use of plants. To be able to work on these ideas 15 years ago, it was necessary to update them. The term narco is more valuable, and the term drugs, for example, today seems insufficient to me. That is why my penultimate book is entitled Plata y plomo. Una historia del arte y de las sustancias (i)lícitas en Colombia.

Una línea de polvo, was written with the children of the future in mind, conceived as a book that would serve as a short and descriptive compendium of the problem that would also tell how visual artists responded to it.

Do you think there is a narco genre?

Not necessarily. It is, in fact, something I have discussed a lot, and we deal with it in the new book we conceived with Harold Ortiz, Mona®co. When you examine the work of artists like Carlos Uribe, Victor Muñoz, Wilson Diaz, or Miguel Angel Rojas, you see that they deal with the subject, but no artist only works with narco. There is no narco genre because the artists themselves go in and out of the issue and their particularity. There is a narco-aesthetic, as a phenomenon that is renewed in Colombian culture, but there are no narco-genre artists in the visual arts.

Suppose you see the exhibitions I have done on the subject. In that case, you will say, “but this looks like a party.” There are hanging papers with little devils. There are flags, pipes, traffic signs, stickers, plastic submarines, a jukebox, or rather a Co-Cola, a very cheerful iconography, which you can read in the key of whatever you want. Still, it is neither narco-aesthetics nor is it documentary. What I work on has something of all that. It is fascinating because that has not been talked about so much. In my curatorial work and my experience in bringing together the works that interest me, the result is different: it is not pessimistic, nor does it judge or accuse. But it is a compendium of how we live culturally with substances and how we find solutions to the problem or try to do so.

Una línea de polvo, became a curatorial work and a series of exhibitions, but that part of the work took a long time to arrive in Colombia, why do you think that happened?

Because people have many prejudices. I presented myself to calls and they rejected the proposal; they said that I was going to make the country look bad. Imagine people in the culture saying that as if it were a serious argument. Also, it was hushed. What can be discussed today is not the same as what could be discussed 10 years ago, that is, we have really changed in that aspect, and many debates have already been aired today.

There has been censorship. I do not talk much about it, but there was. We managed to have the exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bogota in 2018. And then I managed to get it to travel, and it was able to be in Medellín, Bogotá again, Cali, and Pereira, all in 2019.

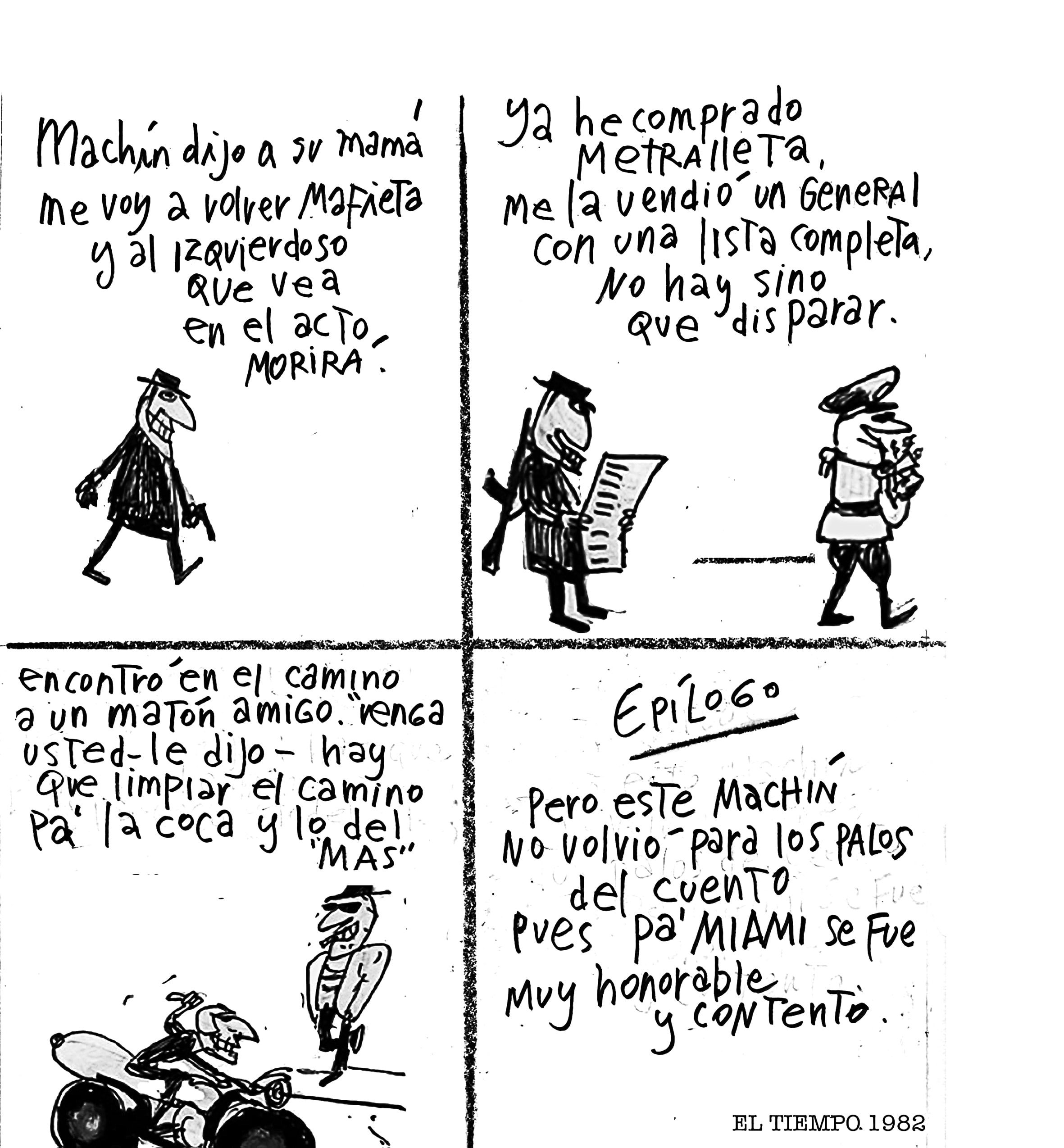

Una línea de polvo, was invited to the Narcolombia exhibition at the end of last year during the pandemic. It was something impressive. I didn’t imagine that it would have such an impact or a large audience. The debates finally took place openly, from the front and the institutional level, in this case, from the Universidad de Los Andes, and thanks to the exhibition organizers, Omar Rincón, Lucas Ospina, and X Andrade. Now we are launching Mona®co. Memorias ilícitas contadas desde el arte, a series of dialogues recorded in each city where Una línea polvo was exhibited in 2019. Where artists, cartoonists, journalists, and representatives of the indigenous communities of Cauca, among others participate. A series of conversations that address a broad spectrum of the narco in each of those contexts: art collecting and financial speculation; humor, opinion and censorship; the use and abuse of substances and the place of sacred plants. All against the backdrop of the implosion of the Monaco Building in Medellin that same year. Mona®co is a new visual compendium on the subject, showing more than 80 works by 40 artists, some of them unpublished.

From your perspective and knowledge, how has art and its positions on this issue changed from the 1990s to now?

Two things have happened. First, with the legalization of medicinal and recreational cannabis, the last in Canada and Uruguay, and the dissemination of therapeutic practices of other plants, we have stopped demonizing substances. We have become familiar with them, and we are discovering them and discovering ourselves through them. There is a change in the collective conscience, allowing a more open dialogue on the subject. On the other hand, more works are being produced, more situations are being created, and the issue has also grown negatively in the continent. Some countries did not deal with it when I started with the subject. The phenomenon has been expansive. For example, in Brazil, they did was not dealt with it, and then, with the crack epidemic, artists began to work on the subject of drugs. In Argentina as well. Rosario, where coincidentally started the path of Una línea de polvo, in 2012, became in the last decade a narco city. Of course, Mexico and Central America too.

With my travels and research, I have gathered more voices. When I did the penultimate version of A Line of Dust in Pereira at the Pereira Art Museum, I had 70 artists invited. What I did was to take the exhibition we had done at the Nutibara Hotel in Medellin months before, along with other works that I gathered. We reached a very high number of artists, equal to what you can have in any international biennial, reaching its ceiling. The question was, above this, what else can be done?

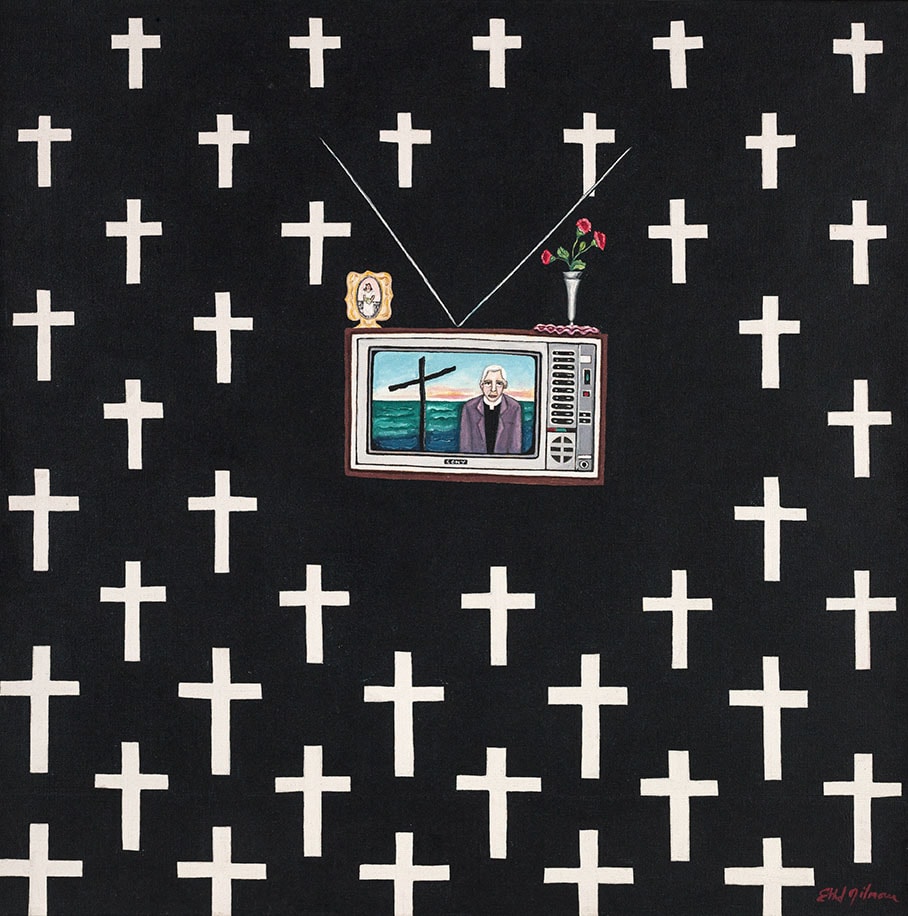

In Narcolombia, I decided to work with eight artists, mainly from Medellín, to make a historical recovery and show the most recent. Among the first, there are two fundamental women: Marta Elena Vélez with El tigre (1981), one of the first works that effectively refer to the nascent narco-aesthetic. And the paintings of Ethel Gilmour, a North American artist who lived in Medellín and one of the foremost chroniclers of what it was like to live in a narco city. Apart from including artists such as Nadin Ospina, Fernando Uhia, and Jaime Avila, we showed Camilo Restrepo’s a ToN oF coke (2021), a ton of virtual cocaine – physically non-existent – available kilo by kilo only through NFTs. In contrast to the versions I made progressively in the last 10 years, it was a small-scale exhibition – which can be seen in the book Post scriptum: Una línea de polvo en América Latina edited by Pierre Valls in Mexico.

In Narcolombia I decided to work with 8 artists, mainly from Medellín, to carry out a historical recovery and teach it more recently. Among the fundamental women, Marta Elena Vélez with The tiger (1981), one of the first works that effectively refer to the nascent narco aesthetic, and with the paintings of Ethel Gilmour, an American artist who lived in Medellín, and one of the first chroniclers of what it was to live in a narco city. Apart from including artists like Nadin Ospina, Fernando Uhia and Jaime Avila, we teach Camilo Restrepo’s ToN oF coke (2021), a ton of virtual cocaine -physically nonexistent- that can be acquired kilo by kilo only through nft. It was an exhibition on a small scale, in contrast to the versions carried out progressively in the last ten years – which can be known through the book Post scriptum: Una línea de polvo en América latinaedited by Pierre Valls in Mexico.

How has the relationship between art and the narco phenomenon developed in commercial terms?

Until the 60s, and 70s, art, not only in Colombia, was a minimal activity. Immensely few people liked it. After the fall of the Wall, when the culture became a spectacle, and the service economy and entertainment industries developed massively, especially in Europe, museums, biennials, and enormous exhibitions began to gain strength as engines of tourism and real estate development. Since 2000 or so, the phenomenon of international art fairs began due to the gigantic financial speculation. Art comes into play because it is very appropriate to manufacture false values. You can put a price on it and say it is crucial and who says it is not. The art market came out of that crisis unscathed, the big fairs continued, and the works of renowned artists continued to be very expensive.

Art has served as a washing machine on the ground for the narco and the financial world in general. In addition, the art system is a pyramid where there are thousands of artists, but few who obtain the benefits and can live from their work, there are very few who sell very well. It is a system that is based on exclusivity. Because of that, it is only possible to offer something unique, extravagantly expensive, and imbued with a fictitious aura, which is finally where the market is monetized and kept alive. And everything is conditional on art and it’s a very narco thing. The high culture turns out to be very mafia.

Gilmour Ethel | El minuto de dios (1980) Oleo sobre lienzo _ 70x70cm