Beyond Pablo Escobar

Narcos Lab is a Medellín-based platform. It generates conversations, does research, and develops narratives on the narco phenomenon in a collaborative and multidisciplinary way. Alfonso Buitrago Londoño is a journalist with a master’s degree in Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies from the Autonomous University of Barcelona. As co-founder of Narcos Lab, he reflects on the phenomenon and is editing a book profile on El Chino, Pablo Escobar’s photographer.

How would you define “the narco”?

We understand “the narco” as a phenomenon that transcends drug trafficking and the business as such, with its links of production, distribution, and consumption. In our historical experience, which has been to look at Medellín in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, we have noticed that the narco has profound social and cultural implications in the urban landscape, in aesthetics, in people’s bodies, in language, in cultural productions, in literature, in cinema, in journalism. This is what the Narcos Lab platform is aiming at: to understand “the narco” as a cultural phenomenon with deep roots in a society that has been dealing with it since several decades before Pablo Escobar.

Although Medellin is a city rich in reflection and there is a great academic, cultural, literary, film, and university production, we have concentrated on what we call “the old narratives” about drugs. That is why we believe that a multidisciplinary debate from a broad perspective was needed.

How do you build these spaces for citizen reflection?

In the first season, we talked about the demolition of the Monaco building. After a series of international productions such as “Narcos” by Netflix or the series “El patrón del mal”, Medellin began to experience a phenomenon of drug tourism. Foreigners came to reconstruct the script they had seen. That caused a lot of discomfort in officialdom because any phenomenon is interpreted as an apology for criminality. Here the narco is understood in terms of traffickers and victims, and in no other way. So the official decision was to demolish the narco building where Escobar had lived.

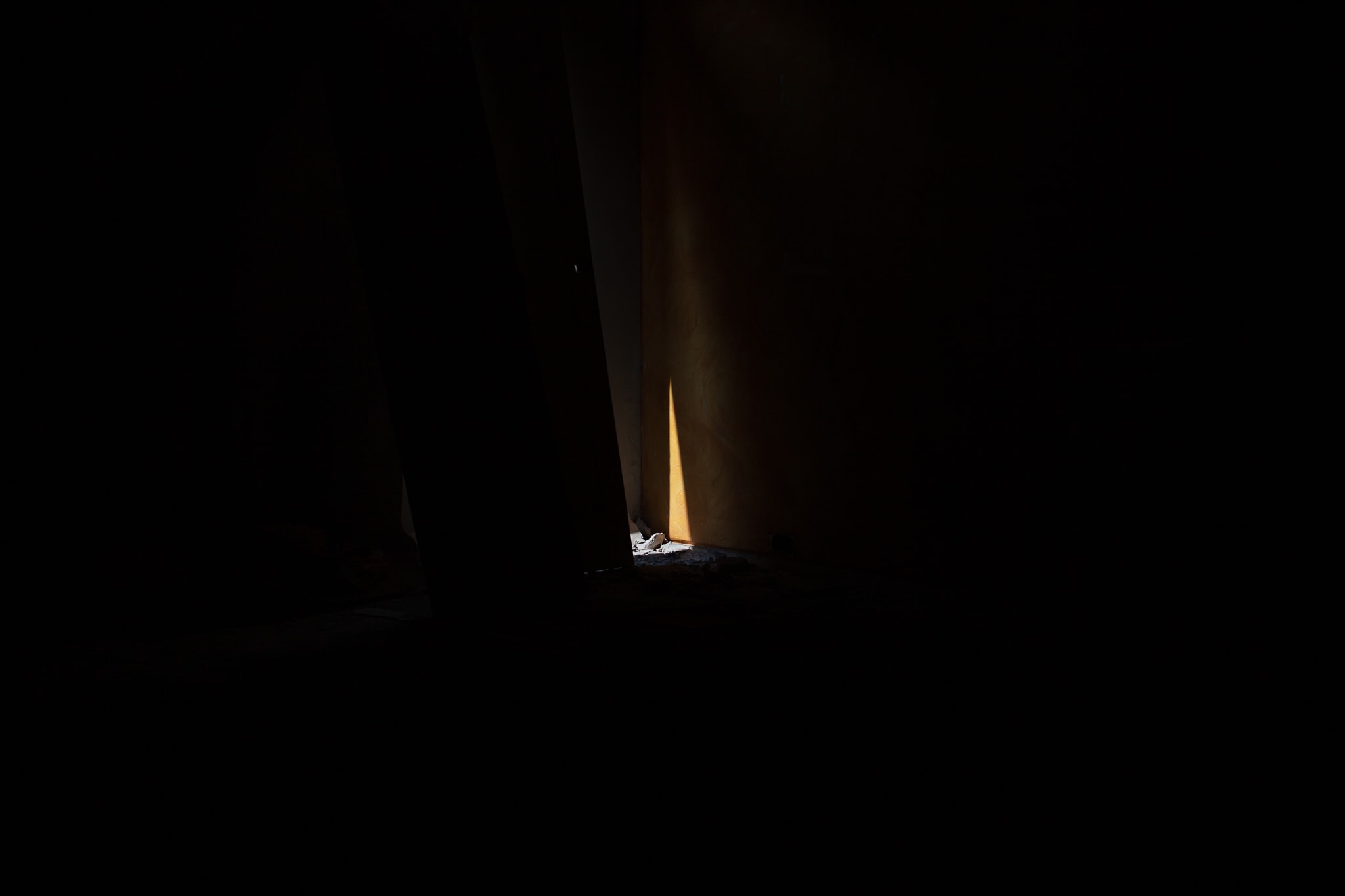

It seemed to us an unfocused, thoughtless decision. It was taking the house away from a ghost. Besides, it was done with an explosion, a symbolic thing, that of repeating the explosions of which the city had been a victim. That is how we proposed discussions with the Museum of Antioquia. We wanted to look at it from anthropology, economics, cinema, architecture, heritage.

We began to talk about “uncomfortable heritages”, those assets that have had a narco past and end up being very difficult to accommodate in society, because we don’t know what to do with them: whether to exploit them, demolish them, hide them, shame us. We chose writers, filmmakers, sociologists, anthropologists, and that was the first part of the conversations.

What is the book El Chino about?

It is part of Narco Lab’s interests; it is the third project we have developed. I’ve been working for four years with Pablo Escobar’s photographer, a friend, a fellow student. He has the most important archive on Escobar’s personal life and the Medellín Cartel. I am making a great profile with a curatorship of his photographs, which we hope to publish soon and which we are financing by crowdfunding.

We can’t hide who we are. I think Chino’s archive is very important because the construction of Escobar’s legend is based on the photographs he took. He was a social photographer, and that’s why most of his photographs were celebratory: Ecobar’s birthdays, public ascendancy, his ranch. Those photos are the ones that have been spun into the entertainment narrative to show the life of that character. I think part of it is to dismantle that script a little bit, to show what’s behind Chino’s life: why he took those photographs and how he survived. I’m hoping that story will help people understand.

You can contribute to publishing the photo book El Chino at this link.