Body and maternity: at the limits of desire

Fabiola Cedillo is interested in how human beings adapt or resist social mandates and roles. Also, what is the limit of desire? For years she has been wondering about the possibilities of human reproduction, naturally or through technology, surrogate wombs, and the commodification of children. She had read everything she could.

So she wonders, as is posed in The handmaid’s tale, who can have children and who can’t. “It seems that we are giving more ground to white people to reproduce,” she says. “Black women are the ones who go less to reproductive processes but not because they don’t have the multiple reproductive problems,” she adds.

She is the founder of the AULA/photography school, created in 2017. She was a finalist of the Portfolio Prize Runner Up of Aperture 2018, winner of 212 Photography Competition photography Istanbul 2020, the COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists of National Geographic, and the “New Generation Prize” of PHM 2017 WOMEN, nominated for Joop Swart Masterclass 2018 and 2019 and winner of the Pampa Energy Award FOLA and FO4CM, among others.

How did you start working on maternity?

What interests me is the objectification of children and bodies and how they become commodities. I could say three interesting phrases: the genetic fetishism in these reproductions through technology. The commercialization of those bodies: both the mother and the children. And capitalist reproduction. As if a child could be chosen as a product in the supermarket, responding to our desires.

The project was always in my head. Now I take it up again after Los Mundos de Tita. Tita is my sister. She has a syndrome, and until now, nobody knows if it is genetic or it happens because she lacked oxygen at birth. I always had doubts about what it would be like to have a child. When I was in a relationship, people started to ask: when are you having one?

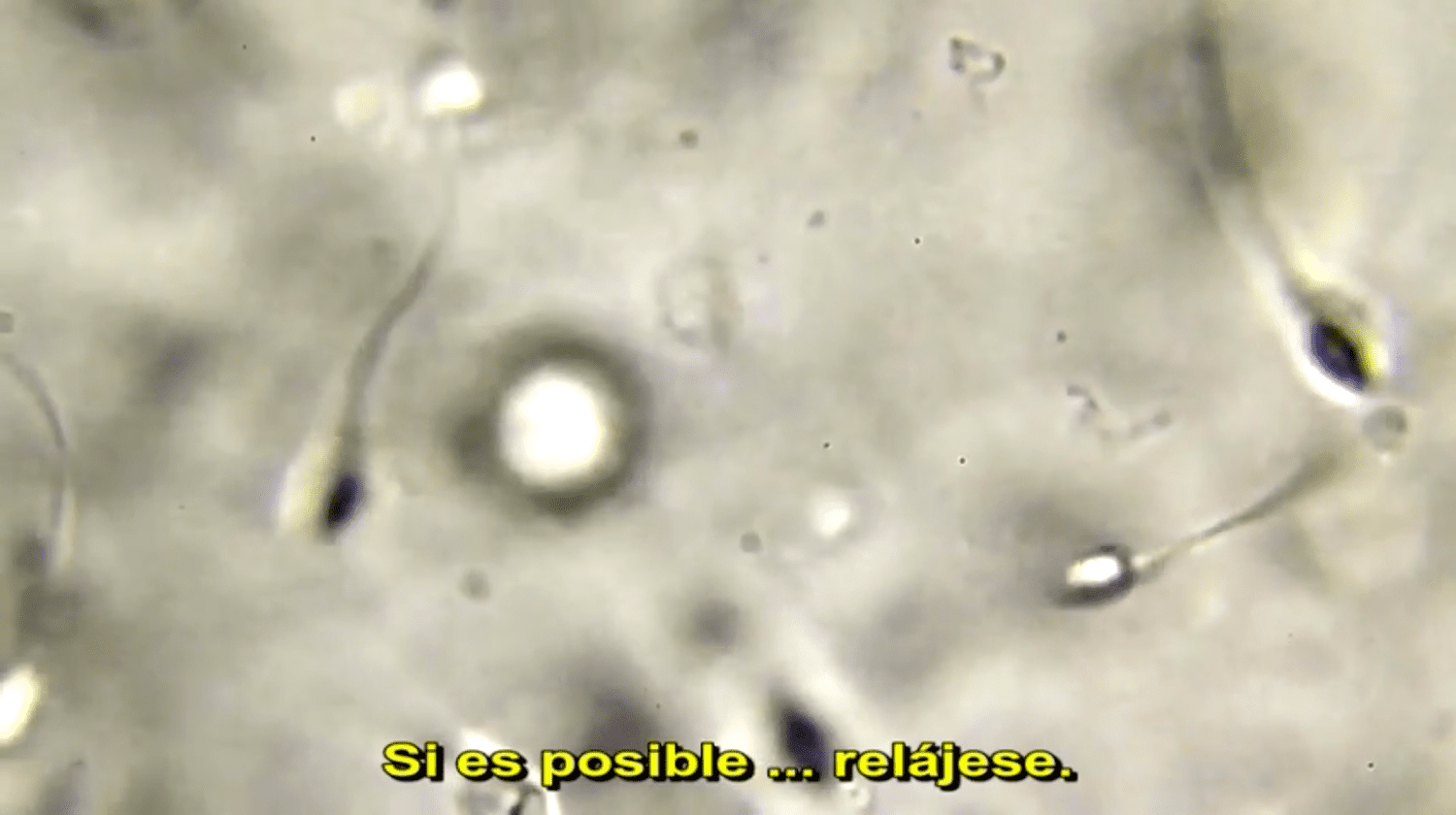

I don’t want to have a child who has the same problem as Tita. I am not as strong as my mother; I have experienced it as a sister. How much technology can help you have almost perfect children, can it help someone who has a pacemaker, can it help genetic diseases not to be transmitted, and can it help prevent them from being shared? Technology is essential for people who need to fulfill their reproductive desires, have those idealized children with their genes, and avoid suffering.

One day, I said: “maybe I don’t want to have children. There are so many children in the world that I could adopt”. But then I thought, “giving birth must be an experience I would like to go through.” One of my relatives had problems with her uterus. I thought, “let’s do teamwork. I can gestate your baby”. Having said “yes, let’s do it” and thinking that this could be possible opened me to other questions; finally, I did not need to carry out surrogacy, but I started to build an ethical, social and emotional stance on this practice.

Fabiola Cedillo

What did you conclude?

I started to find out about surrogacy. In many first-world countries, surrogacy is not legal, so European people look in Asia or Latin America for people who can gestate their children. Some companies unite the future parents with the surrogate. They tell them that it is an “altruistic” act, that they are women who have already had children, that it is a favor and that thanks to this “favor,” they will give you a part of the 10 thousand dollars we will charge. In Europe, it might cost $40,000 to do it.

You look at the statistics, and they are women who are in a state of precariousness and tremendous vulnerability. We do not see any volunteer doing a Ph.D. in London saying, “oh, yes, I will interrupt my life to lend my womb for nine months.” Let’s not fool ourselves: it’s a kind of prostitution. These are practices without laws, women without rights.

How far can we go with this that we desire? Who are we pleasing? Can technology replace God or turn the one who uses it into Him? My research continues. It is not a photo-documentary project. I face stories, my thoughts, the fears and dreams of people I know. I face situations that happen in different communities, and in every place and moment, I photograph openly, letting the image give way to multiple readings. Nothing is just what it is. There is always more…

How did you approach the stories?

I open this conversation; everybody has a story to tell. People tell me about themselves, their acquaintances, and social pressure from their parents. Someone always has a point of view or an opinion to give. It’s true: we all go through that. We all came into the world through a reproductive process, and as sexual beings, we have had these ideas in our heads.

I realize I’m full of biases. I know that what I am now, I won’t be tomorrow. I may look back and think: why did I believe this? I am willing to accept that I change. I don’t want to do a politically correct project or tell absolute truths, I want it to be human.