Photographer Cristina de Middel convinces the Tijuana athletics team to train in front of the wall that separates Mexico from the United States. If this were a note from a sensationalist newspaper, that could be the headline. And on the cover would be a photo of one of the athletes pole vaulting in front of the wall. The first reading could be humorous. Cristina usually takes refuge there: she has a sense of humor that escapes her eyes and is reflected in the way she looks at the world.

But looking closely, what she’s saying is something else. Cristina, a multi-award winning artist associated with the Magnum Agency, knows what she does and does it with deep love and respect. She entered the world of photography when the idea of photography as something capable of changing the world was already in crisis. She started as a photojournalist and as such she portrayed other people’s misfortunes until she discovered that she did not want to be part of it. She didn’t give up using the testimonial image, but she integrated it into something much deeper. In her gaze, the migrants who take risks are heroes, and she wants to show them as such. Cristina is brave. She does not hide behind canon or laurels. She doesn’t repeat herself. What she does from her overflowing imagination is to show the world as she sees it: a rich, contradictory world, where what we perceive as true may not be true, and where humor can tell us more about the state of the world than many of the works that we usually see.

We see you at the Tijuana border: where everyone is looking for blood, you find horses and images that sometimes seem like dreams. When did you realize that the language had to be expanded to other places?

I entered photojournalism when I was entering this crisis, and I already felt that the audience was exhausted from always being told the same thing in the same way. I have not lived the golden age when you went to Vietnam and came back with photos that changed the internal politics of the United States and made the population mobilize to end the war. You know? I have never experienced that political power of awareness of photography. So, I see it differently. What I like is that it is understood. I think there is a mixture of that and giving my opinion, and my opinion has to do with how I see.

I worked as a photojournalist for 10 years. It was a cumulative process. One day, in Haiti, I was in a hospital working with Doctors Without Borders and a woman came, looked at me as if piercing my soul and said: “Why don’t you help me?” It is true that I could help her because what I had spent on the ticket, on the camera, on editing the photos, on living in Haiti, which is very expensive … My defense was: “These photos will help,” and according to I said, I realized that I didn’t believe it.

Another moment that impressed me was when I was in Syria to cover a crisis. Syria was receiving refugees from Iraq and began receiving refugees from Lebanon; it was seen as the axis of total evil, as “the” terrorist country. I went with the idea of showing that it was a country that received refugees from neighboring wars. At one point I took a bus and came to a place thinking that there was the war… and everyone was on the beach. It sounded like the joke of a Spanish comedian named Gila who called the enemy on the phone to organize himself. It’s ridiculous. I spoke to a soldier and said, “Where exactly is the war?” And he told me that I couldn’t go in there, that it was a military swimming pool. So, then, on television they bombard with the message that everything is destroyed, and there are two buildings in two streets to the north, the rest is normal, people are on the terraces, in the discos. I said, “I don’t want to be a part of this, I get out.”

How did you detach yourself from the dilemmas around representation, creation, and the truth that photojournalists are so concerned about? How did you overcome that tension?

For me it is a very outdated debate, of course. We have known this for a long time: when you connect the dots between very different things like a story and reality, sometimes they overlap and sometimes they don’t. And that doesn’t mean that it is less rigorous. You can keep learning through fiction. More than ending the debate, it is about lowering it from the pedestal of the truth. It would be a bit like “killing your father.” In that sense, “the truth does not exist”: there is no necessary link between photography or any form of narrative, and the truth. And nothing happens, you can go on. You realize and that’s it, Photography does not lose an iota of its intrinsic value.

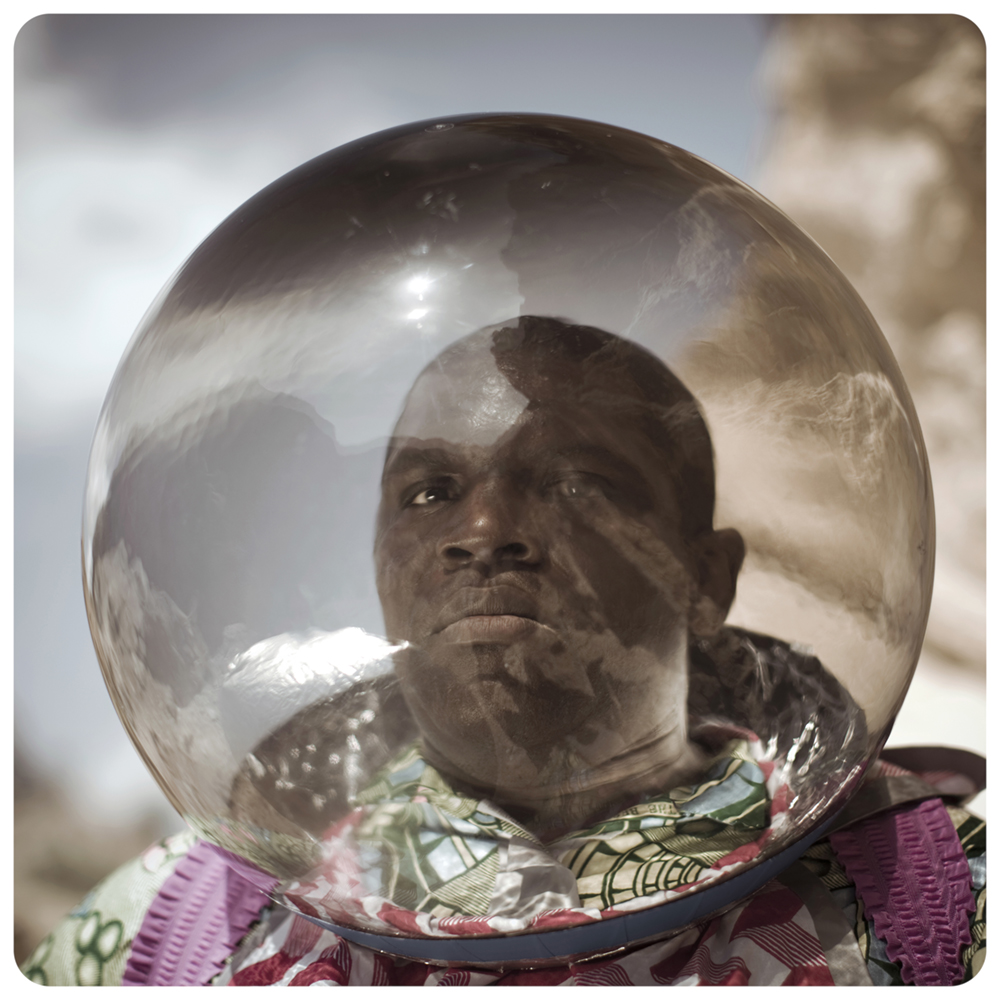

Speaking about truth: with your work Afronauts you have fooled us all. We thought it was made in Africa and then we found out that it was made in the backyard of your house.

The problem is not that I “have cheated on you.” You have believed that in order to talk about Africa you have to be in Africa. Because of the constructions that we have made. All this would have to be rethought to be able to use photography as a more complete tool, with the video camera or the camera with the moving image, for example. I am not trying to give lessons but it is a reflection that everyone has to do.

Is it difficult to get away from the demands around documentary photography?

Photography has a burden, as if it could not exist far from the truth. In no artistic discipline, communication, literature, advertising, cinema, comics do they ask you to be true. But with photography, it happens. Why?

I have had to face a lot of debates, answer interviews about my way of working, about what is documentary and what is fiction, and what moral problems it has… These are battles that I have to deal with every time I present my work. Now, it is about to be published in a French magazine and they asked me for captions. And what can I put you in the caption of the photo? “Benito Juárez’s face cut out with Popocatepetl in the background.” They’re damaging the whole narrative, so that’s already a battle. That is, I am not going to explain to you that a literal description of what appears in the photo takes away all the symbolic reading that you can give to an image because you need it to be true and you need it to be Cartesian responding to something. Those are battles. What I do is say: “My photos do not have a caption. If you want, don’t publish it, but don’t ask me for a caption.”

Your work seems closer to Buñuel than to Cartier-Bresson.

I don’t think that in talent I am close to one or the other, but I am in influence and inspiration, I would say that it is fifty-fifty. In any case, Cartier-Bresson was not a documentary maker, he was an artist. Within the Magnum family I am closer to Cartier-Bresson than to Capa. But it would still be half and half because the motivation and themes that I chose are not just surrealism per se, it is not just doing an aesthetic, conceptual or symbolic exercise. I use that language to talk about contemporary issues because I think it works and I think it can help us understand the world better and find solutions to its problems. Just like Greek mythology, which responds to concrete situations and concrete events that are repeated so much that in the end they become myth.

You may have to invent a genre, right? Like a documentary surrealism, like a documentary fiction.

We are already entering the world of labels. For me it is documentary because I am not talking about myself. I’m talking about migration, a space program, racism, prostitution. I share my questions but it is documentary. In that sense, I am closer to Capa than to Buñuel.

After Afronauts you established a strong link with Africa, even though the photos were in your house.

It was because I was curious and I like to travel, but I have done very little documentary work in Africa. Through Afronauts they began to call me a lot and to connect me with the continent. They invited me to exhibit there and I wanted to know what the reaction of Africans would be to projects like Afronauts. I ended up very involved with the Lagos Photos Festival, which I curated for a couple of years and I still have a very strong bond with them.

There I did This is What Hatred Did, which is a counterbalance to the apparent superficiality of Afronauts. It was a collaboration between two visions of two continents based on a story entirely theirs, which is the book My Life in the Bush of Ghosts by Amos Tutuola: a horror story that tells the nightmare of a child whose town is attacked by slave hunters. We made a real version of the story, we staged the whole story in Makoko a neighborhood where all photojournalists go to nurture the miserable and dangerous image of Africa. I find it nice to have a much more subtle dialogue with photojournalism. I decided to do it in Lagos to influence the need to deepen and give a voice to the people there.

Give voice?

Yes, give them a voice to participate in the telling of a story. I was not doing documentary work, I was looking for an excuse to show them in a different way, no the traditional photojournalistic one. We both tell a story that is theirs. It was as if we confronted our visual libraries and our ways of seeing the world and understanding it through photography.

Makoko is a pretty rough neighborhood. To enter you need permission from the clan chiefs. I had to work with them as models and in the places where they had chosen. It was like: “You take the picture here.” I could suggest but it was not up to me. With each scene, for example, I would say to them: “Now we have to take the picture of the goddess”, which is like the spirit of a superwoman, that’s how she is called in the book. The lady is like a ghost who has 400 children under her skirt, the archetype of fertility. So how would you represent it? We read it, we said “put on like this”, “I would do it like this” “let’s try like this now”. And little by little we were building the visual version of the story together.

For example, in the book there was a ghost party. The first idea that came to me was to throw a ghost birthday party. I started looking in Lagos for the typical wedding cake so that it would look good in the photo and it was impossible, they don’t celebrate with cakes like that there. They have other desserts. So it was my big production expense, which wasn’t much either because they were Halloween jokes… But the cake cost me $200 and I had to find a lady to bake a cake for me.

Do you fall in love with the places?

I have fallen in love with Mexico. I arrived at the end of 2014. I had a friend whom I had not seen for 11 years. Then I went with Ramón Reverte, from the R.M. publishing house. He taught me the Mexican universe: I was in Mexico City for a week, he introduced me to Graciela Iturbide, Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, he took me to the bookstores… On the second day I already knew that I was going to stay. I remember that we were going to the La Lagunilla market, we were waiting at the traffic light and suddenly a ventriloquist crossed the street with his doll. I thought: “I want to live in a place where ventriloquists crosses the street.” Every place has a photography associated with it, and I liked that point of tension of always having to be attentive. I felt at home in that sense, at humor level and everything. I feel more distanced, freer, less responsible. Mexico is a place that inspires me and where I can learn a lot and where I think I can leave something too.

I am partnering with artists again. Now with Buñuel, with Bolaño and so many who chose Mexico.

It’s a fantastic place. That is why it took me so long to do a project on Mexico, I was very careful to see if I could contribute to the debate. Now I am finishing a project on migration. I use Jules Verne’s novel Journey to the Center of the Earth to explain the passage of migrants through the Mexican Republic, from the southern border to the northern border to reach Felicity, the official center of the world which is in the United States, just a few miles from the border, in California.

It is like a journye to the center of the earth but on the surface.

I use fantastic literature because it helps me explain a fascinating part of Mexico. It seems important to me to show it like this, with its incredible landscapes and the richness and spirituality of its customs. It is the beautiful part of Mexico, with the geological wonders, the caves, the butterflies that come here to reproduce, the whales. And I confront it with the most documentary part of the journey, like the passage of The Beast. Then there are characters along the way that have a mythological point such as the bosses, the hitmen, the deserts. There are very good people and very bad people as in any great feat, in any great sense of adventure or travel.

In one of those photos you show someone on a wall jumping.

I play small games to change the perception about the migrant and show him as a hero, because he takes a journey for which you need to have a lot of courage and resistance. The issue always struck me, especially since Trump came to power. I don’t think more empathy can be generated through the testimony of: “Oh, poor people, whatever…”. I like to go back and think about the moment when you decide to travel and leave your family. It is brutal. There are very poor towns in Guatemala where everyone gets together, they choose three teenagers, pay a coyote to cross them to the United States and once there they send money to the entire town. Imagine being 14 years old and having that responsibility. Would you take a trip like this to save your family, when you were fourteen years old? Okay with Greta Thunberg, who went on a hunger strike in front of the Swedish Parliament: And very good for her. But there are a lot of other people doing amazing things that are perceived and presented in a way that is neither fair nor correct to me.

Then there is The Beast, the bribes, the police, the migra, drug trafficking and violence associated with human trafficking. That is the documentary part, I respect it one hundred percent: I get on the train with them, I take photos of them, they tell me, I interview them. It helps me to better understand what I’m talking about. I make a balance between the strictly documentary part and the more imaginative part. Then on Instagram and in contests they choose a more imaginative part… but hey, but the other is also there and it will be seen when the project is finished and the book comes out

In your work there is a political project, a political intention.

My work is more serious than I present it. I usually go towards the joke or the irony but I work very seriously. It is a game but it is a professional one. It interests me that people understand, not from the point of view “you must be solidarity” but “you must admire”, in this case. The same admiration you have for Greta. Your grief is useless, your admiration is useful.

You mentioned that it is possible that you will leave photography.

Yes. Right now I am with three projects in different phases. I want to do studio things, moving images, experiencing documentaries with films or on screens of any size.

Is the testimonial over?

No. Before it occupied all the space, now there is a gap that you have to fill with information that the testimonial does not give: atmospheric, emotional and sentimental information. I want to document myself when I try to document others, record what goes on in my head, what associations I make, what references I have when they are telling me something, how I am translating it. That is what I am looking at. It’s like an expanded documentary because I’m going to listen to you but the monkeys with saucers that I have in my brain will also be in the background.

Rumor has it that you have a notebook where you write down all the things that monkey dictates to you. There you paint, draw, take notes.

I write down what I hear on the street, coincidences that I have seen… Mexico is full of those images, Africa too, but Mexico more, or perhaps I understand it better. These are moments that overlap in my head, forming a collage of reality: You take something that belongs to a place and a context and take it to a place where it shouldn’t. Neurons are connected in a very interesting way. Sometimes I draw pictures. There are many schemes, photos that I could never do, impossible projects like touring Spain in alphabetical order of its towns. I like to fantasize about these ideas because offshoots are born from those impossible ideas.