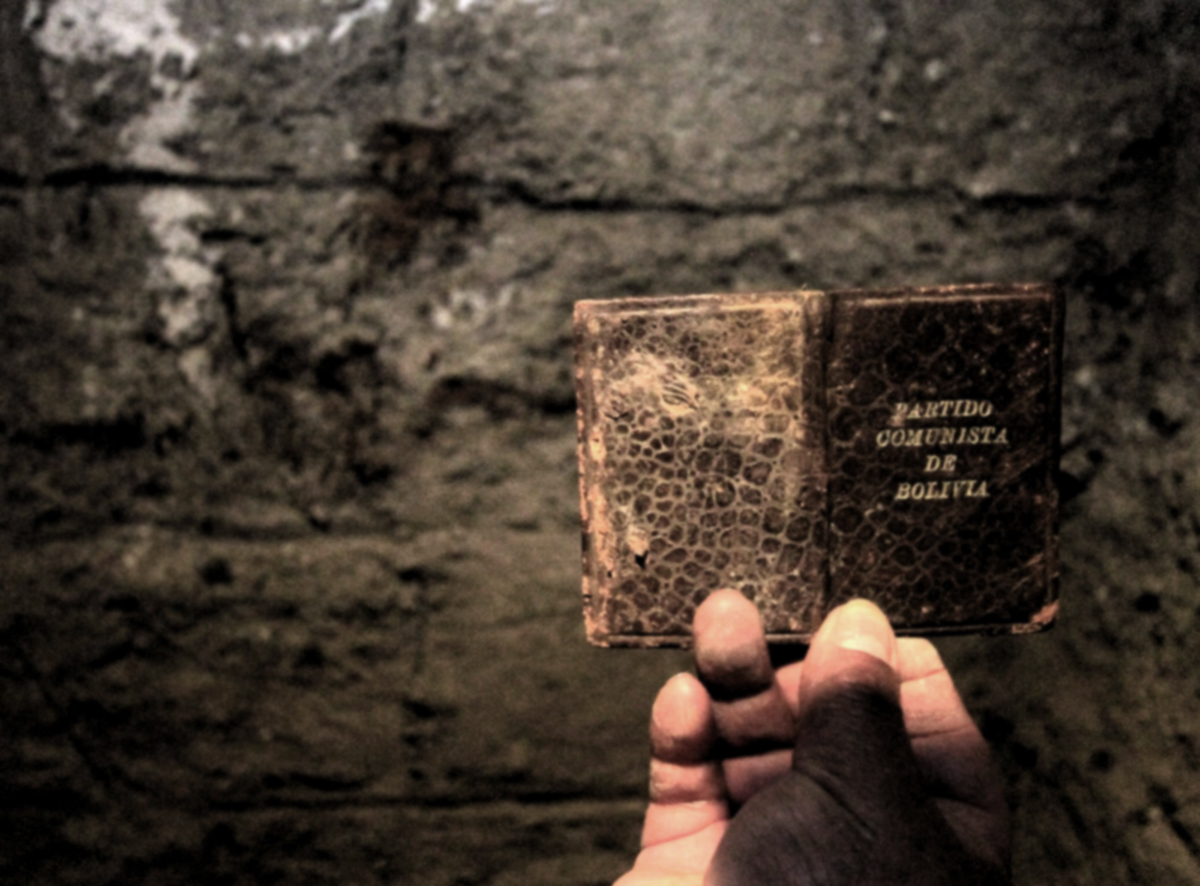

Bolivian photographer Wara Vargas discovers things everywhere. Like when she found a little leather notebook that says “Communist Party” among the debris of the Government Ministry, where they tortured during the dictatorship. She, also, makes discoveries in her own dreams: it was there where she visualized for the first time her emblematic photo series of cholitas underwater.

Wara studied Social Communication and she specialized in Press Photography at the Instituto de Periodismo Internacional José Martí in Cuba. She worked in Bolivian journalistic media, she has won awards and has exhibited her work in several countries, such as Brazil, Uruguay, Mexico, Italy, Germany, the United States, Colombia and Spain. She is also part of Ruda, a collective of eleven female Latin Americans photographers.

She made a series about kawaii culture that, imported from Japan, promotes that every member builds their own character with their own identity. Until the middle of the last year, Wara portrayed traditional midwives in Bolivia for Nat Geo. But then a very serious political crisis began, which ended with an attempted coup and the resignation of Evo Morales. Due to the protests and the blockades it was difficult to access the area and then the pandemic arrived.

With the National Geographic COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists, Wara did work on blind workers in the quarantine and street performers whom she accompanied during the strict confinement. “They were closer together, because they are people who are generally on the street all year,” she says. There are almost thirty families, who live about ten blocks from Plaza Murillo and with whom she shared hours and hours, as if she were part of the house.

Once you said that your father taught you “the art of stopping time”. Why?

My father is a visual artist and a photography lover, he was crazy: He always had new cameras, all analog. He lent me the smaller ones, automatic ones, but he was teaching me how to handle a Konica. I played to be his assistant, it was to make me do some little things. As some cameras did not have a photometer, he made me some illustrations with suns so I could begin to learn, probably I was seven or eight years old. The NGO he worked at had a laboratory, I went in with him and we did together the photographic processing.

After my parents broke up, my mom and I came to la Paz. He would send me some monsters of analog cameras, all borrowed, then I would return them and send him the negatives. It was a relationship between we had between the two of us: He rwould pick up my negatives and send me the photos. When I finished school I told him that I didn’t want to travel and that I preferred a camera as a gift. It was a Konica, it had three lenses. With it hanging on my neck, I started the University.

How much of your work talks about the country’s history?

Bolivia has always been portrayed by foreign people who always had shown us as poor: cholas women on the street, selling. I think that in some way, the photography has been very elitist, it was done by foreigners or the same Bolivians who had modern equipment. And poverty sells, of course.

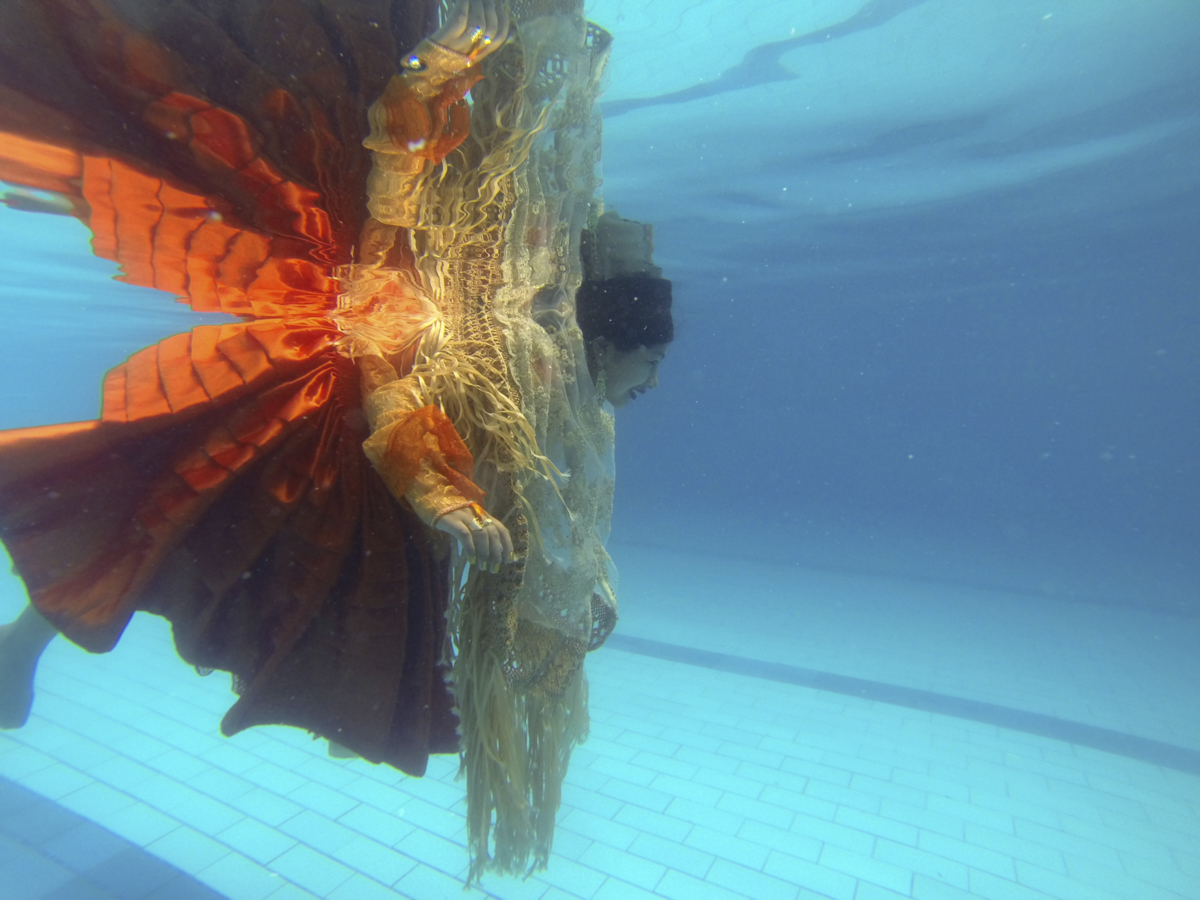

Sueña (dream) came out very intuitively, it was not planned. I had a dream where I saw the cholas muses floating. I thought: “Wow, that has not been seen, we hardly see the cholas on TV”. Until recently, been a chola was not a good thing, I have some friends that take off their chola dresses to go to the university because they were discriminated against a lot. Having a chola grandmother was the worst that could happen to you. I think that over the last years this was camouflaged by the Anti-Discrimination Law. But some time ago, some hidden videos were known in Santa Cruz, in which a cholita sat in a very VIP restaurant and, although they did not throw her away, they did not attend her. Although now there is more inclusion, more cholitas on tv and deputies cholitas.

There were never any cholas on fashion advertisement, they only appeared as housewives or humble people, ruined in their lives. Those were the stories that they told us. I think that the visual is very important because it is forming the image of these children who, perhaps, are in a circle in which they think that if the mom is a farmer (which is not bad) all your aspirations cannot go further.

How was the work process?

It started six years ago, I get it with time. Because either I did not have a pool or did not have the equipment. But I always came back to this idea. One time they sent me to take photos to the first model agency of cholitas, and I said “wow, at last!”, it was a top agency, the super luxury cholas. Unlike the western models, who are all straight, here they were told: “you have to show your hips, you have to contour more”. The lap of the skirt has to be very rough because the fabric has to move.

Under the water it was complicated, and it was an interesting training. It was three months of work where we put our heart into it. The bombín (hat) is very expensive, it costs like a thousand Bolivian pesos [140 US]. They were so excited the first time we went, that the second time they wanted to put the bombín underwater. Later we dried it until the next time. They said “¡I am going to get in with my jewellry, and me with my shoes!”

And what happened after submitting the work?

I didn’t know what I had done until I uploaded my photos to the website, I didn’t realized the potential of Sueña. We did a sample of the series in the La Paz cable car and I understood the dimension of it when I saw a little girl carried on the back of a cholita, whose eyes were filled with light when she saw the photos. It is about breaking up the imaginaries of the poor chola or the domestic worker. Also, there are those who think that the only way to fit in this world is to dress Western.

The other day I saw two cholitas about fifteen years old, something that I had never seen in my entire life. They were luxurious, the girls were beautiful, it was the day of love. They took selfies with a stick! I was shocked, before, girls and adolescents did not wear cholita dresses.

In this one you made the cholitas talk under the water; in another work you managed to make the walls speak, how was it?

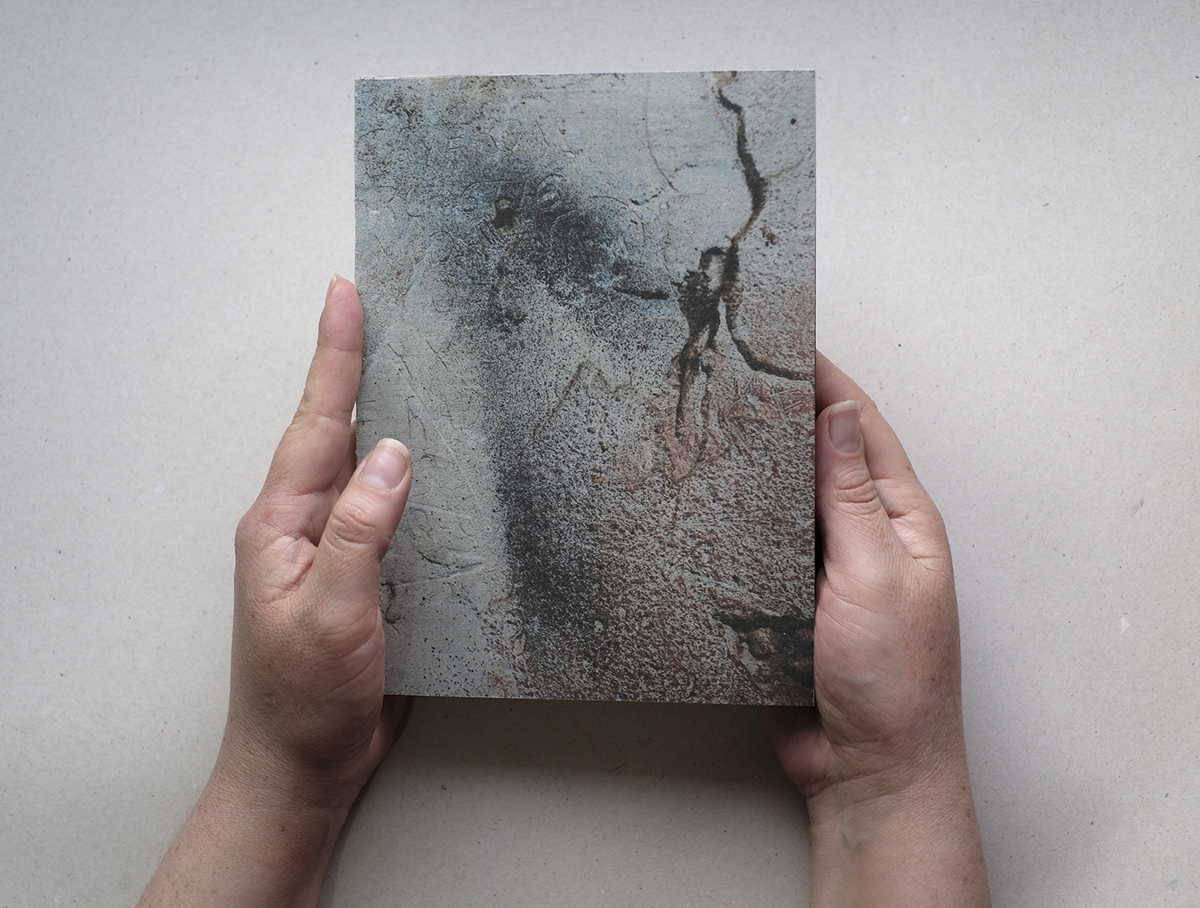

The project began in 2011 when in Bolivia, during the government of Evo Morales, they discovered some hidden basements in the lower part where they tortured people. They invited the press because it was going to become a museum of historical memory. I worked for a newspaper, and although I studied that process, it was the first time I felt how strong it was. That day entered journalists and the victims that were tortured. They didn’t know what that space was because they came there blindfolded. Only when they entered did they recognize it: while they were walking, they were crying. A lady had to sit down.

That day was a shock even for me, every wall had inscriptions made with rocks. In some parts it was written in blood. Elsewhere it says “here we were tortured”. It was written with fire, I suppose with a lighter. They felt that they were going to pass away and wanted to bear witness. I took photos of the people that came, of some walls and then we left. But before that, I went away from the row and I was kicking the ground because there was rubble, newspapers from that time. Among all that, a small notebook appeared, which says “Communist Party of Bolivia.” I took a photograph of it.

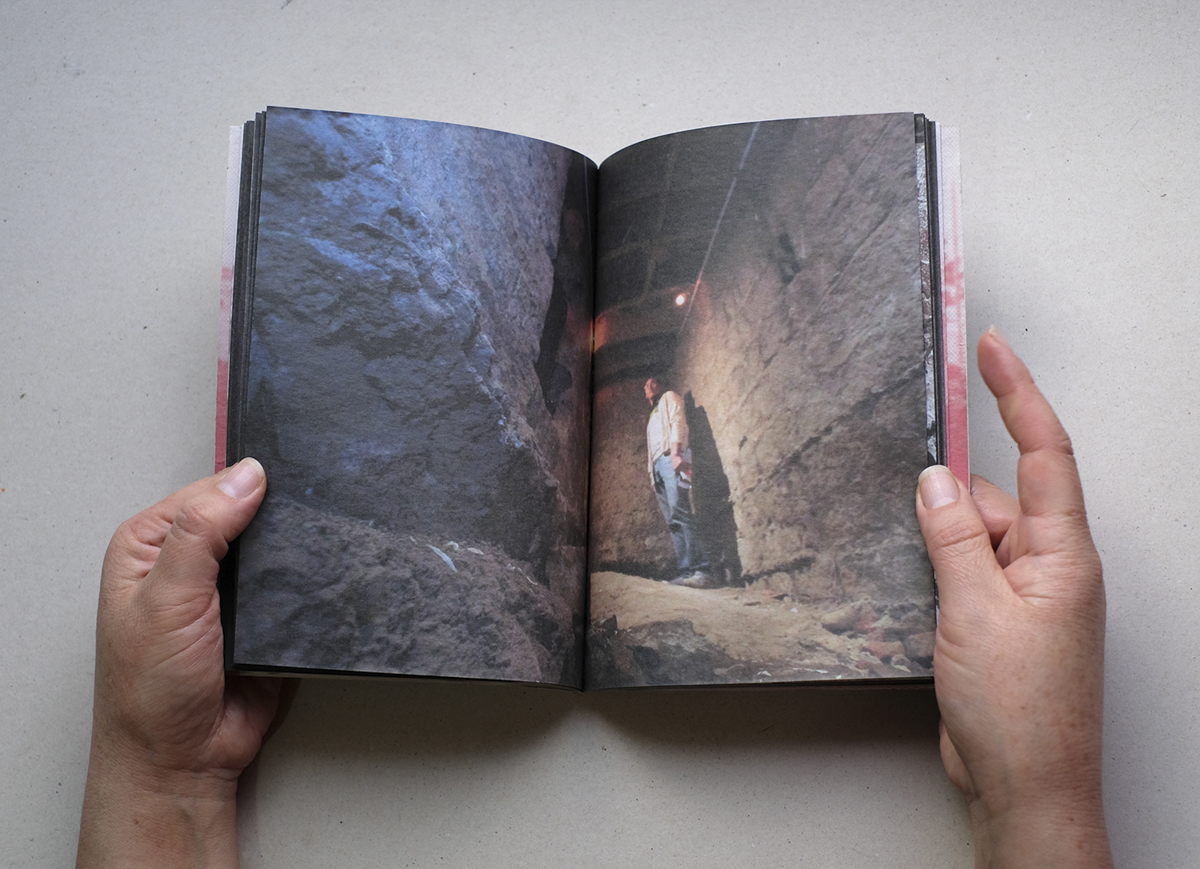

And that’s where the project born? How did it become a book?

Yes, I sought to give voice to those walls, I started to contact the associations and I began to accompany them. I did several series for the newspaper, with some interviews, other works from the tent where they claim their rights. Little by little it was setted. This year I decided to finance it and produce it as a fanzine, it has come out of quarantine. I sew them, I print them. One of the stories told there is that of Don Julio, a lifelong militant. He died during the protests when the President resigned. As some other militants had already died, I thought: “It can’t be possible, they’re all going to die and we won’t have the book.” The book was born out of that urgency, the only objective was for family members to have it. In the audiovisual presentation of the book, a testimony recorded some time ago is still heard, in off. It is Julio’s voice.