A flat land with rainforests and swampy plains. A flooded savanna where birds, snakes, felines, rivers, streams coexist. But, also and fundamentally, what is in the plains are women and men on horseback. There, in this geography that Venezuela and Colombia share, is born a very own idiosyncrasy: the rider culture.

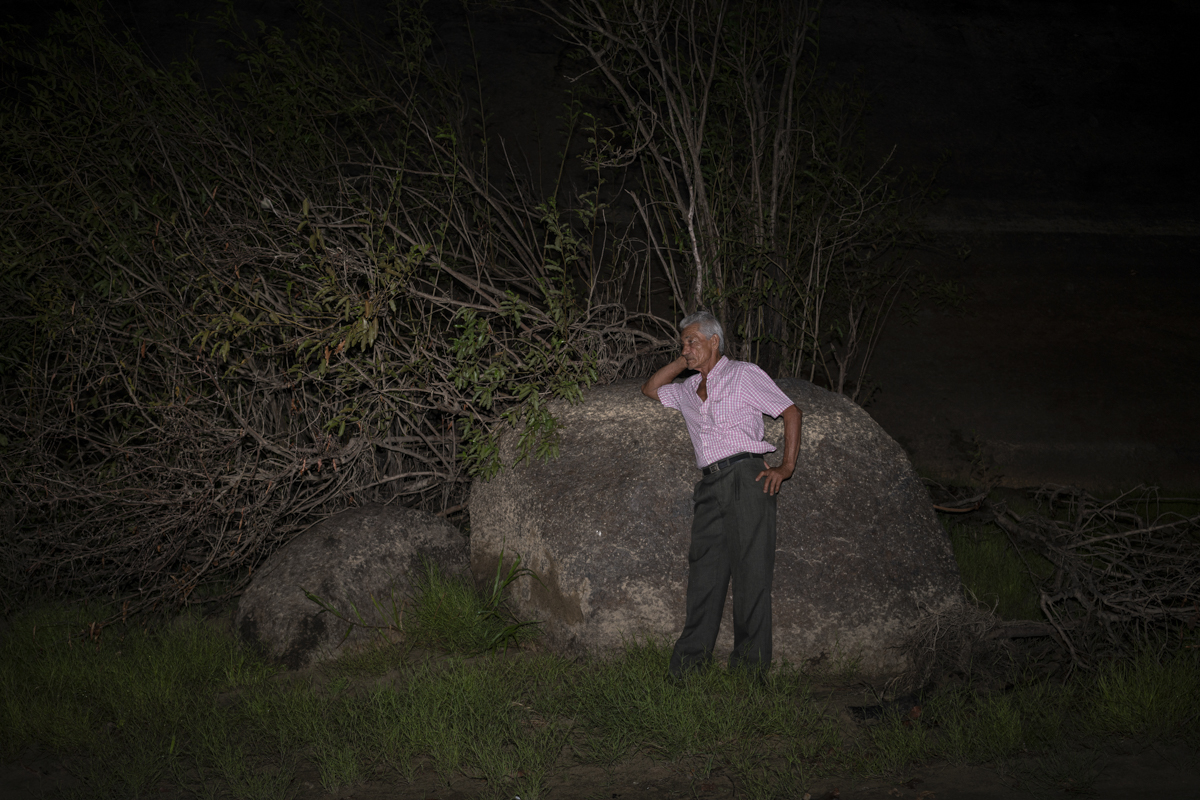

The challenge that Juanita Escobar faced first was to understand the territory in its intimacy: inhabit it at its own rhythm and then portray it. In 2007 this self-taught Colombian photographer left her natal Cali to move to the department of Casanare, part of the Llanos Orientales region.

Ten years later, Juanita still lives in the Llano, throughout all this time, she learned to ride: “the gallop of the horse planted me in this land”, she told about this experience that lead her leave her old life. “I was twenty years old, with a few days at the university that soon I changed for the school of life that opened up for me in the immensity of the plain. I learned my way of life riding a horse” she wrote.

Juanita won the Colombo-Swiss National Photography Award in 2009 with her project Gente-Tierra. Among other works, she also published Llano (a book with forty of her photos) and was coauthor of Silencio: un llano de mujeres.

In your book Llano you state that telling that story is telling yourself. How do you re-read this statement today?

My dream was to tell deep stories with the camera. I arrived wanting to tell stories, to become a proffesional photographer. I wanted to do documentary or photography direction in the cinema, and I started working there as a technician. One thing that I found when I went to the Llano was still photography. I became a photographer and also I connected with a culture in a very deep way. I was young, I came from a city, Cali, where I used to walk side to side. I did not imagine in advance that it would be so many years. Upon arriving and photographing the fauna and flora, I felt “I want to stay here”.

I learned a lot through my great work fellow Francisca Reyes, an anthropologist, she took me at that pace, to that way of drawing a route of investigation. I say that telling this story is telling myself because there have been many years in this place, riding a horse, learning things, and learning to look and tell stories. I was very young, I came from a city, Cali, where I walked side to side but to arrive here was to learn that I wanted to keep walking but here and that was great and still is. All the stories that I tell are from this territory, the closest and the long term ones.

How do you feel that your way of photographing was changing during this time?

At the beginning there was a lot of change because when I started, the same thing happened when you write: It’s easy to see the changes over the first six years. In the book of women, Silencios, compared with Llano and the last works, the difference is abysmal. The focus on the first book was to construct profiles and I put more emphasis on writing, testimonials and information. The photos were a record, to show women, and to point objects of the culture. There was an introspective and intimate atmosphere, but it was not manifested in the photos. Now I feel that all of this is not only in the words, but the photo also embodies it.

¿How was this path?

The idea is to build atmospheres by joining the photos, as in the cinemas. One learns to tell stories and to create with more awareness about the rhythm, the atmospheres, the main elements of a character, a story or a problem. It has to feel this transition of the story, it has to be reflected in the story.

Your work is marked by the intersection between gender and territory, how is that search?

My first book (Silencio: Un llano de Mujeres) was my way to arrive and getting to know the territory. And it was through their trades, from their time and their friendship. It was not only over the action, the meat, and chores, but a plain of a normal life, of family and cultures. That link was made by women, that link in a way of being with that territory from various perspectives, reflecting on machismo and roles. It was an exercise of being in a place in an open way, with time to the stories to come out.

Of the four departments that make up the Colombian Eastern Plains, you have traveled two and are going to work in the others: can you say that you are in the middle of your trip?

Yes, in fact I would like to live here. I am almost living in a town that remains on the shore of the Meta river and I move to other places to make stories, but this is my place. Now I am on a project: I want to start a community newspaper with eight young people and strengthen the written and visual narratives to tell chronicles. In the first place I want to do it with a few close people and see how to move forward.

How do you cross a territory like the one you are portraying?

My dream was to know the Amazon and the Orinoquia of Colombia. It’s like half a country and is really difficult to get to know this culture and this territory. I had two great masters: the anthropologist and photography director Sofi Oggioni, she took me everywhere; we got a work in the Llano for six months where all was by water and we had to document it, she on video and me on photo. At that time, she had to return because she has a daughter and need to continue working. Our ideal was to stay and tell stories from photos and audiovisuals. Go over rivers, the flat land with tropical forests around because they are plains like the pantanal, flood plains where all the species are in the savannah boxes there are birds, cats. Knowing that territory and the rhythm of the people who inhabited it was like “Wow”. I wanted to see and know but through looks, through people and the love for that territory and a way of exploring it. It was also for this reason that on horseback I was able to feel another rhythm and find stories with more time.

Howis the rider culture?

I feel that perhaps we are very familiar with the horse from the cultures that came to America and that errant way of getting the territory. The fixed point is the horse and from there a life is planted or made, one looks at the horizon, a family is built, a sense of old age, of love, of the relationship with the land. I think the latter is the key: errant cultures in the sense of turning in the same circle. They are mobile but they are not cultures that are related to sedentary lifestyle, but to be moving. Here the riders are riders of tropical savannas. They are not only from the plain where there are grasslands. Before, they were called in the Colombian plain “horseback Indians”. It is a binational culture with Venezuela, in fact there is much more flat land there, much more territory and another roots, more national.