Earth likes blood

Photographer Gianni Bulacio was born in Jujuy, the northernmost province of Argentina. He had always had the concern to tell the stories that surrounded him. Since it was difficult for him to do it with words, he decided to “shout it out with images” and chose the camera as the tool. Little by little, he was studying the rituals, trying to understand their meanings, their origins, and the syncretisms of which they are the result. He discovered, suddenly, that the offerings also include blood.

He has a degree in Photography from the National University of Tucumán, Argentina. He works as a reporter, is a contributor to the Associated Press and Reuters, as well as a contributor to UNHCR, the United Nations. He received the first prize in the Museo en Los Cerros photography contest in 2012, the first prize in the 2015 World Nomads ‘Great Scapes’ contest, and an Honorable Mention in the Jujuy province art salon in 2019.

Gianni Bulacio

How did you decide to tell stories close to you?

It was conscientious. I always liked being able to tell what my world is like, the place that surrounds me, its culture, its beauty. From the beginning, I was interested in being able to tell from the rites. For example, rituals that take place beyond the hill. I take many photos of the mountains and the hill. I think you have to know how to think about it, with your time, to understand the wonders. I was always terrible at telling it with words, so I was interested in being able to shout it with images.

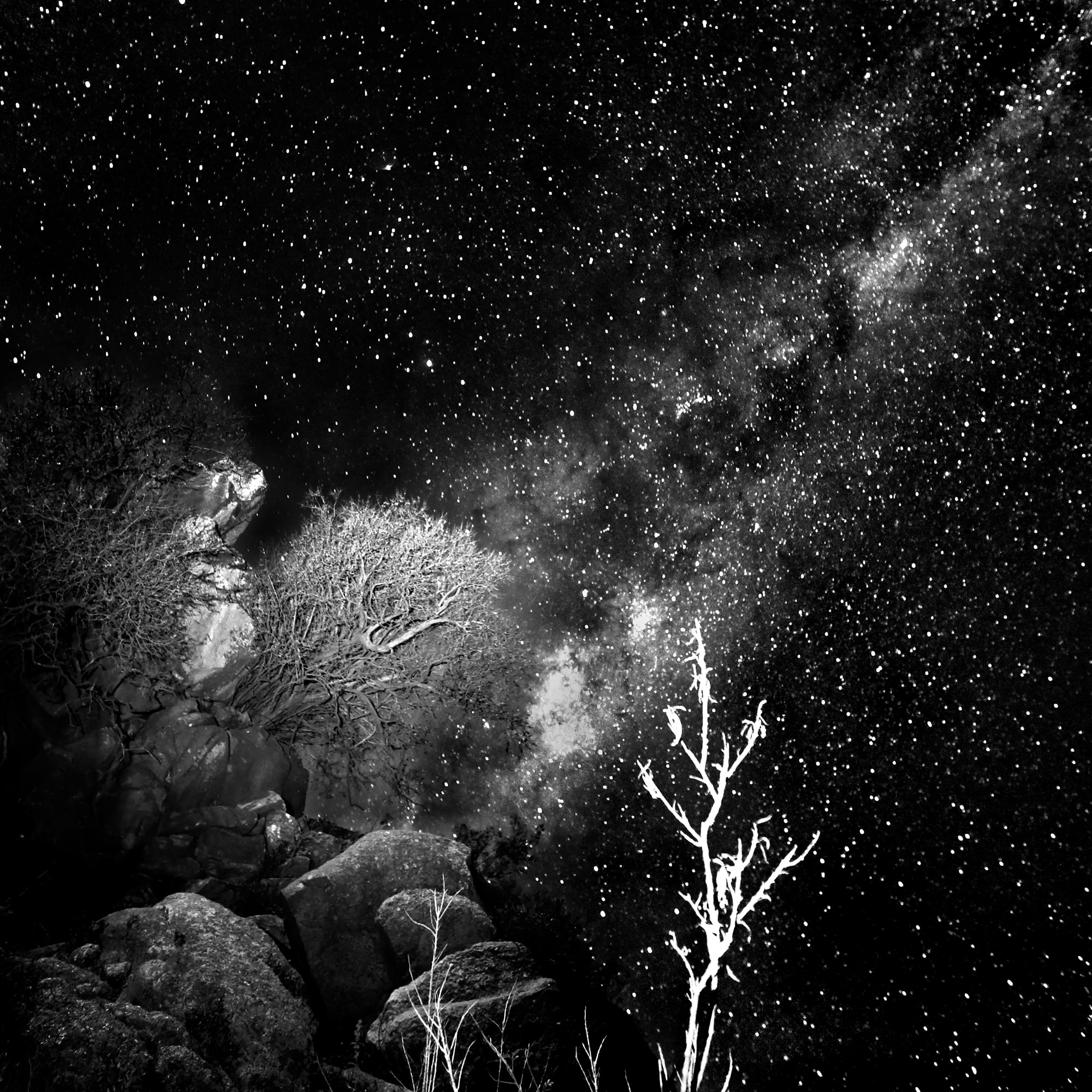

Scream the beauty and scream, too, the silence of this place. This is how some projects are born like my book Sueño. My book was born from the contained cry, from the necessity to tell my place intimately, to talk about the mountains’ soul. I think that all my work is about the need to be able to tell my place. Not only Jujuy but, in general, the Andean culture.

What does Sueño narrates?

The book is born from the desire to tell a territory, a place. It was conceived as a sensory journey experience, but with the drama of a dream. Starry nights, many landscapes, and also portraits of girls and boys appear in the book. Somehow, I see in their eyes the brightness of the stars. It makes me think that it is the brightness that comes when someone dares to dream infinitely. It was born from an initiative of the hills, which I had already been doing. The idea was born in a photobook workshop at the Museo de Los Cerros, dictated by Julieta Escardó. There we were going to learn, to think, three days of a beautiful process with our work.

The selection was a bit difficult, it was a process in which a lot of people, opinions, heads were involved. I opened the game to all the workshop participants, even to Julieta. I came with photos of boys and girls dressed in typical cultural costumes, typical of what is said so much about the magical realism of the Andean culture. They are children dressed in tinkus costumes, caporales costumes, saya costumes, and different dances. It occurred to me to mix it with the landscape because it seemed like a good way to tell the territory in a dreamlike way.

The idea was that it was a book that could fit in both hands. I had made a small book once, four centimeters by four centimeters. Many of the people grabbed it and held it to their chest, with both hands, like that gesture when it seems like something very beautiful to you. So, I also wanted this book to have a little bit of that and I wanted it to be a book that travels, that accompanies you.

Why did you focus on offerings?

I was born in Jujuy and raised in the Andean culture. Since I am very young I make offerings to the earth. That is why I was interested in inquiring about them, to understand more about the Andean worldview. I began to travel through the communities and discovered the Casabindo party. My interest is in the ancestral consciousness, the land, the people. Casabindo fascinated me, that party drove me crazy, that mixture between the ancestral rite and the Church stuck there with its processions and its virgins. Casabindo is a festival that takes place every August 15 and is of the Virgin of the Assumption.

In addition to the procession and the dance of the samilantes, there is bullfighting (de la vincha) in which a bull with a bullfighter enters an arena. Unlike Spain, what the bullfighter has to do is snatch a headband that he puts on the bull, with silver coins. And nothing more. The bull is not killed, injured, or harmed. And that headband that the bullfighter manages to snatch, will be an offering to the Virgin in demonstration of faith and courage. At the same time, the samilantes dance with lamb’s quarters, and that is also given to the Virgin and the Earth.

I kept investigating and found that in many of the Andean countries offerings for the land are made. I traveled to Bolivia to meet the Fiesta del Tinku, which in the Quechua language means encounter. It is a meeting that has the character of an offering. About 80 communities come together and, between typical clothes and a lot of chicha, they fight to offer their blood to the earth.

They are fights that occur between communities. Men fight, women fight, children fight. There is no winner. There is no loser. They face. They split their faces. They bleed, hug each other, and each one returns to their place. This put me before a new type of offerings. So far, I had seen food. There the people offered their blood. I began to discover that the Earth likes blood.

My research drifted to that side. I returned and found a book in the library in Buenos Aires that talked about another ritual that is done in Peru, which is also an offering of blood to the earth. I traveled to Peru, always with my interest to see what this ritual was about.

It is a ritual in which communities come together on top of a mountain, five thousand six hundred meters high, which is quite high. I had to train for several months. A battle is fought there. They go up, on one side of the mountain there is a coalition of communities (two or three communities) and, on the other side of the mountain, another coalition of communities. They face each other in the center, there is like a small valley. There are two thousand people against two thousand people and stones are thrown with slingshots.

You also made a documentary.

I made a documentary because when I went to Tinku I felt like I was getting lost a lot just taking photos. I was interested in being able to capture the music or the songs, the dances. I recruited a mate, who knew how to film better than I did, and the two of us left. We prepared our armor, helmet, and went into battle. I was interested in resuscitating them from within. I am always interested in telling things from privacy.

I had seen that there was no such record, they were all videos from afar, with a lot of zoom. I said “come on, whatever the Pacha wants: if we go out, we go out and if we don’t go out, we don’t go out.” It was difficult to get there, but we spent a month there sharing with the community and building this documentary based on very simple questions such as: “What does it mean to give blood to the earth?”, “Aren’t you afraid to go into a ritual battle of that magnitude?”, “What happens if they have a friend in front of them, they throw the stone at him?”, “What is the role of women?”

The documentary, Hierve la sangre is about questions, about they telling about this ritual and the offering of blood. Many people from another culture can see them as barbarians. The comments, sometimes, are like a misunderstanding. But, in essence, the belief is that if you give your blood to the earth, the potato, the tomato will grow better. If you live in the mountains, you depend purely and exclusively on the land: you need to hold on to those beliefs. Just as people, on the other hand, believe in God or in Allah. It is important to be able to give back to the earth what it gives you, to be able to thank him. For the Andean culture, it is very important to thank the Apus, who are considered the spirits of the mountains.

The ritual has been insane. Luckily we were able to go back to tell about it, but many people do not have the same luck. They say that when you are there, in the middle of the battle, your blood boils. I named it after that.