Eunice Adorno: How to survive in community

In 1968 Eunice Adorno’s father was part of the student movement that mobilized to the Plaza Mexicana de las Tres culturas. That day the police beat and arrested thousands, and killed hundreds of students. Even now, it is not clear enough how many. This is known as the “Tlatelolco massacre”. She grew up with that story about her father. Maybe that’s why, thinks Eunice, years later and already as a consecrated photographer, she started to work in a project about a student’s house.

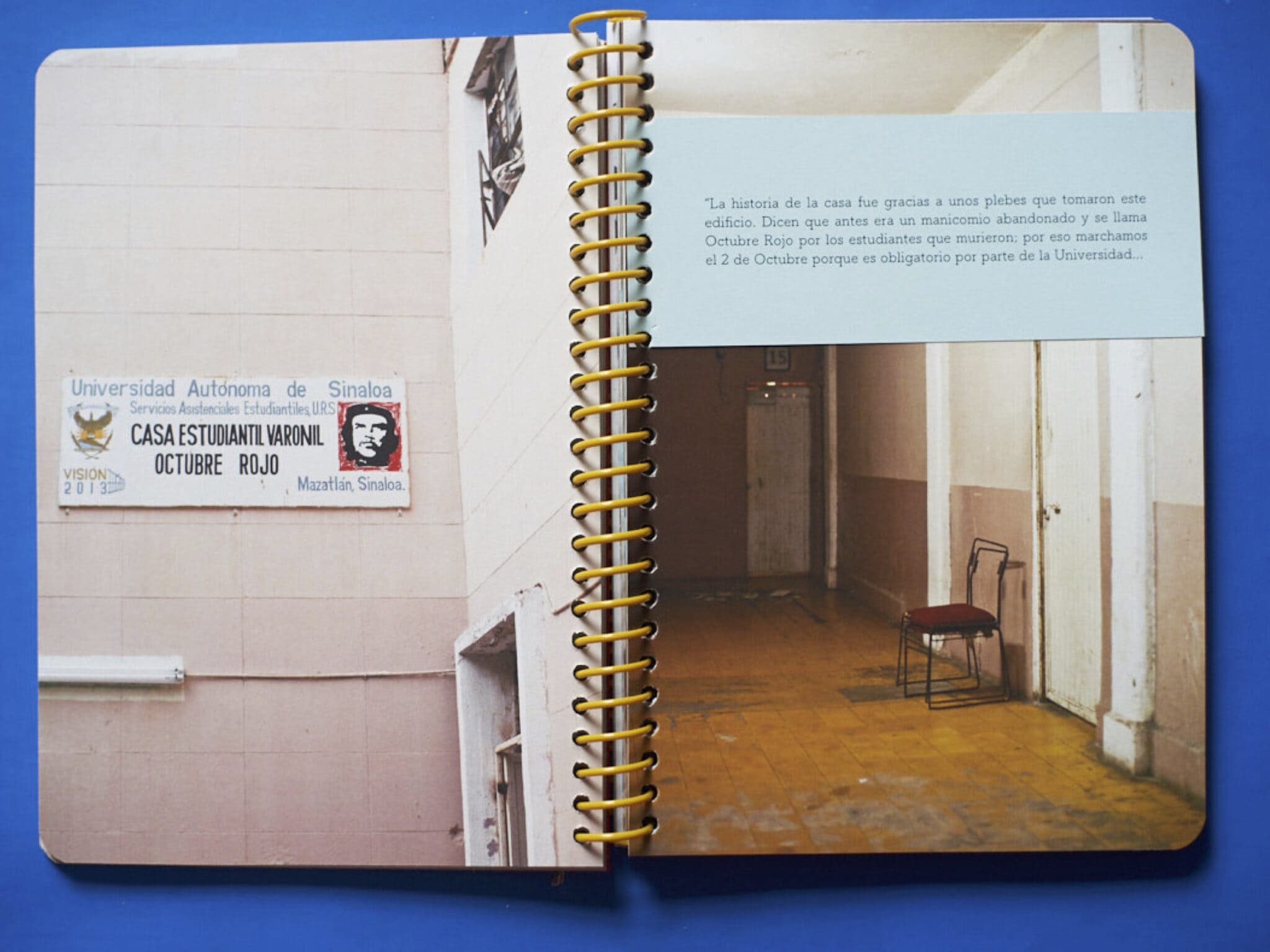

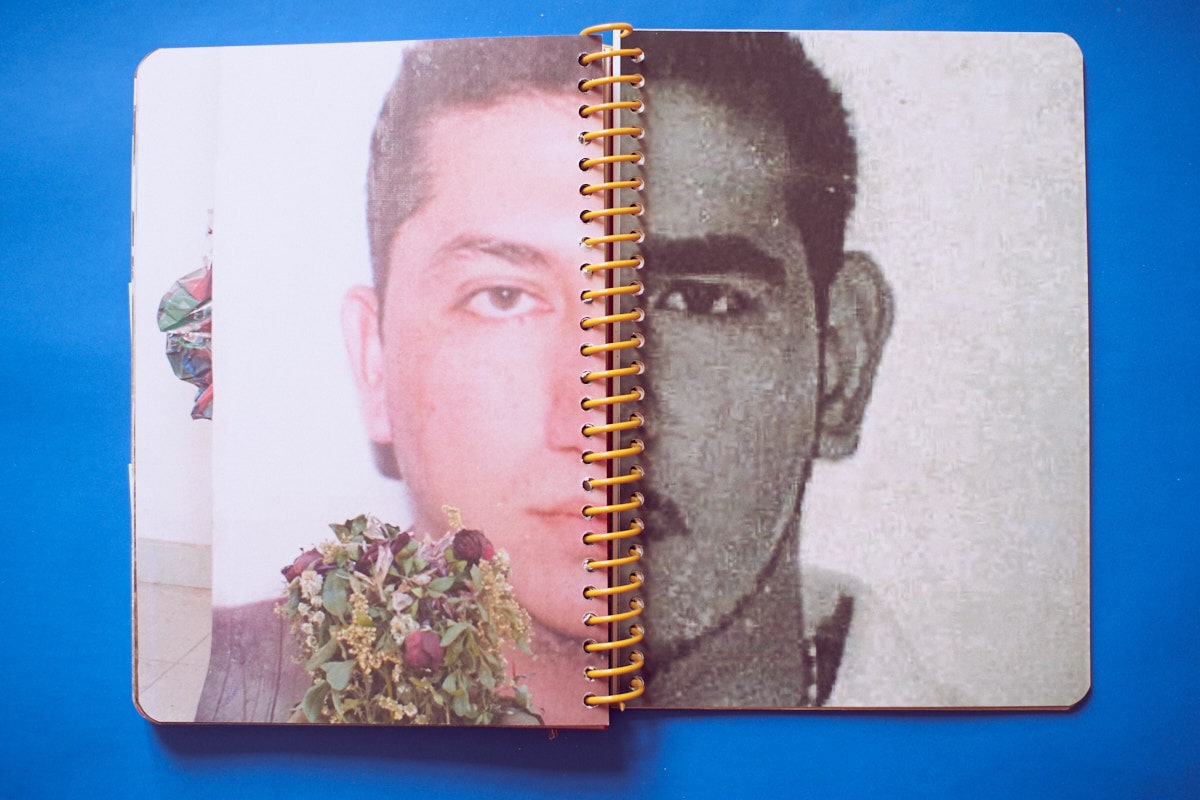

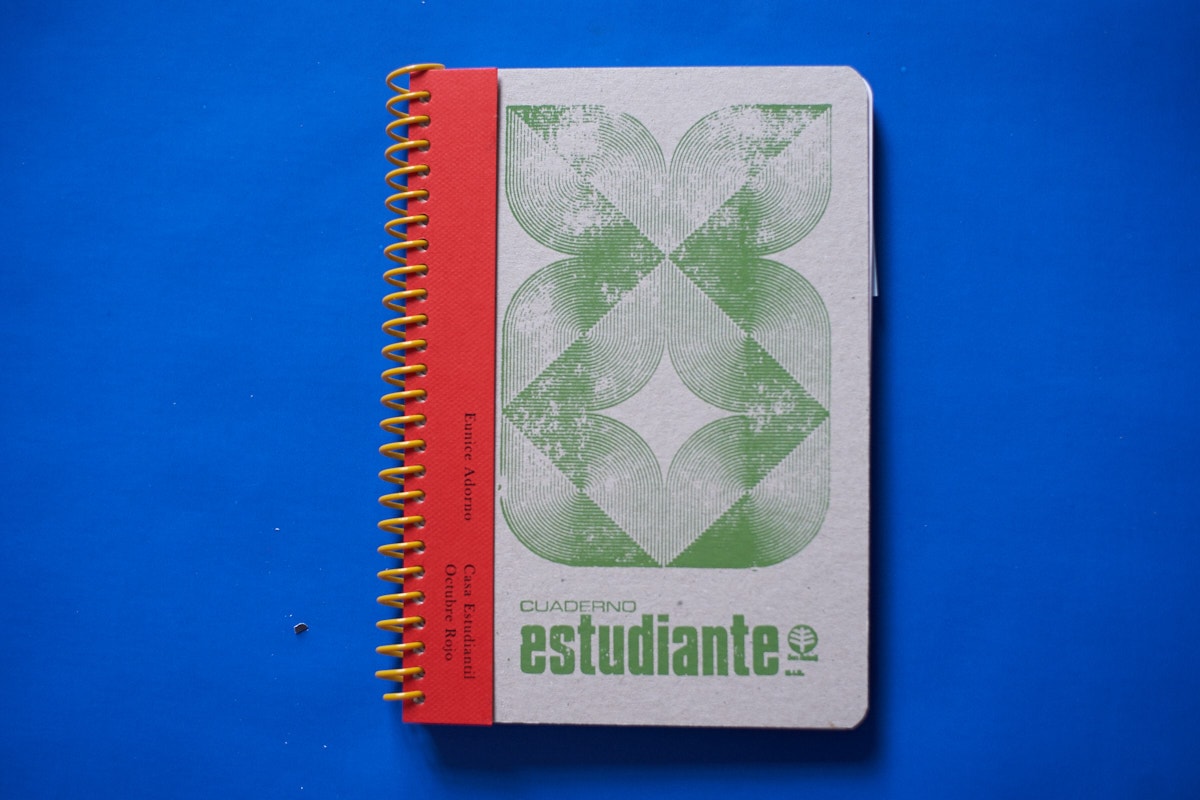

The result was a book, Casa estudiantil Octubre Rojo, a publication made by the sweat of a brow and product of six years of work in a student shelter in Mazatlán Sinaloa. What experiences must humble students go through to get to go to university? What is it like to organize their day-to-day when resources are scarce and violence appears all the time around them?

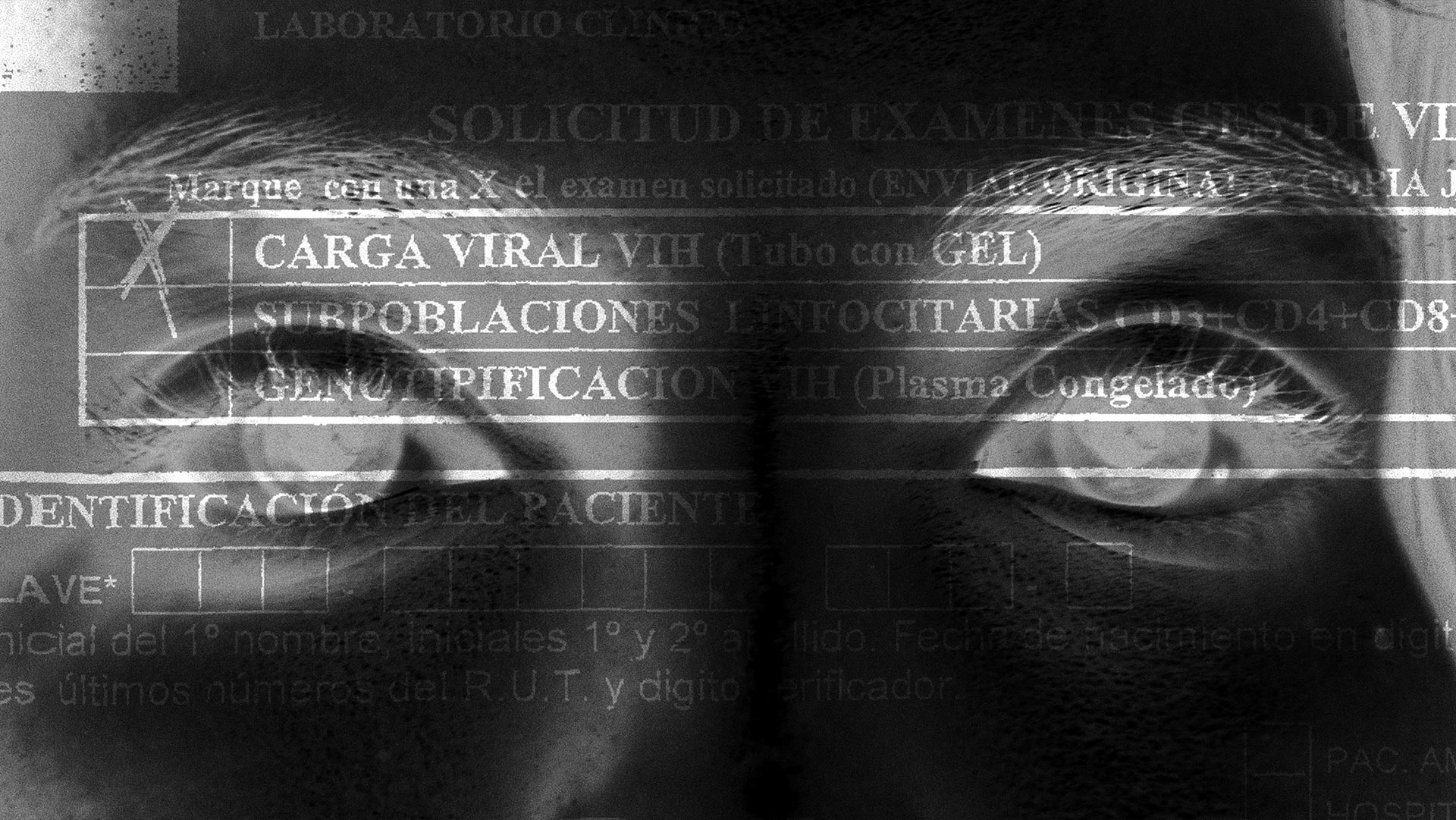

Eunice Adorno – Casa Estudiantil Octubre Rojo

Eunice studied photography at the Image Center, participated in the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass in Amsterdam and has more than a decade of experience in photojournalism. She was awarded the FONCA scholarship to young creators for several consecutive years and the Fernando Benítez National Culture Award in 2010. Among other things, she was also nominated for the Rudin Prize for Emerging Photographers (2012) and won the IMCINE economic incentive for writing a script in 2014.

Eunice Adorno – Casa Estudiantil Octubre Rojo

Eunice Adorno – Casa Estudiantil Octubre Rojo

How did you get to the production of the book Casa Estudiantil ‘Octubre Rojo‘?

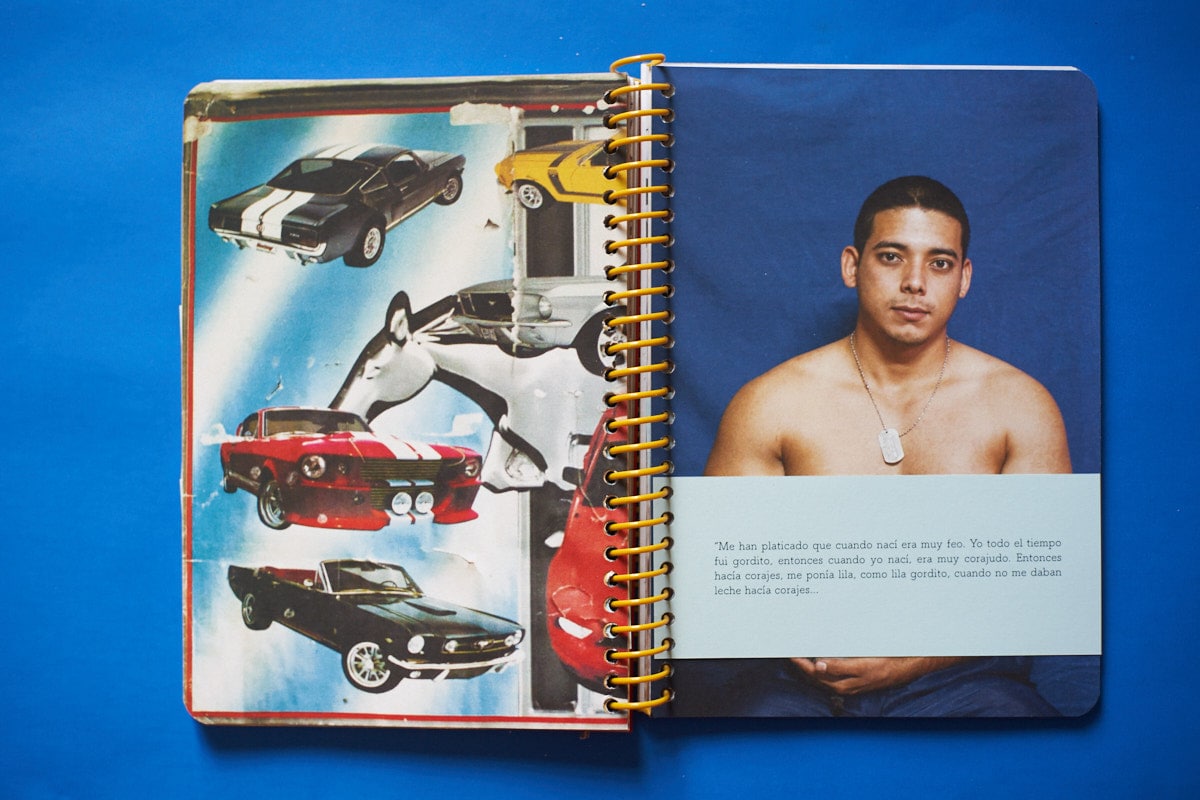

I was doing an investigation about the violence in Mexico when the “war on drugs” started. It was when this house came up and I stayed a long time. The book compiles all the documentary recordings that I made with young students from Mazatlán, Sinaloa, in northern Mexico. It is an area known for the drug trafficking loop, which has done so much damage to young people and education.

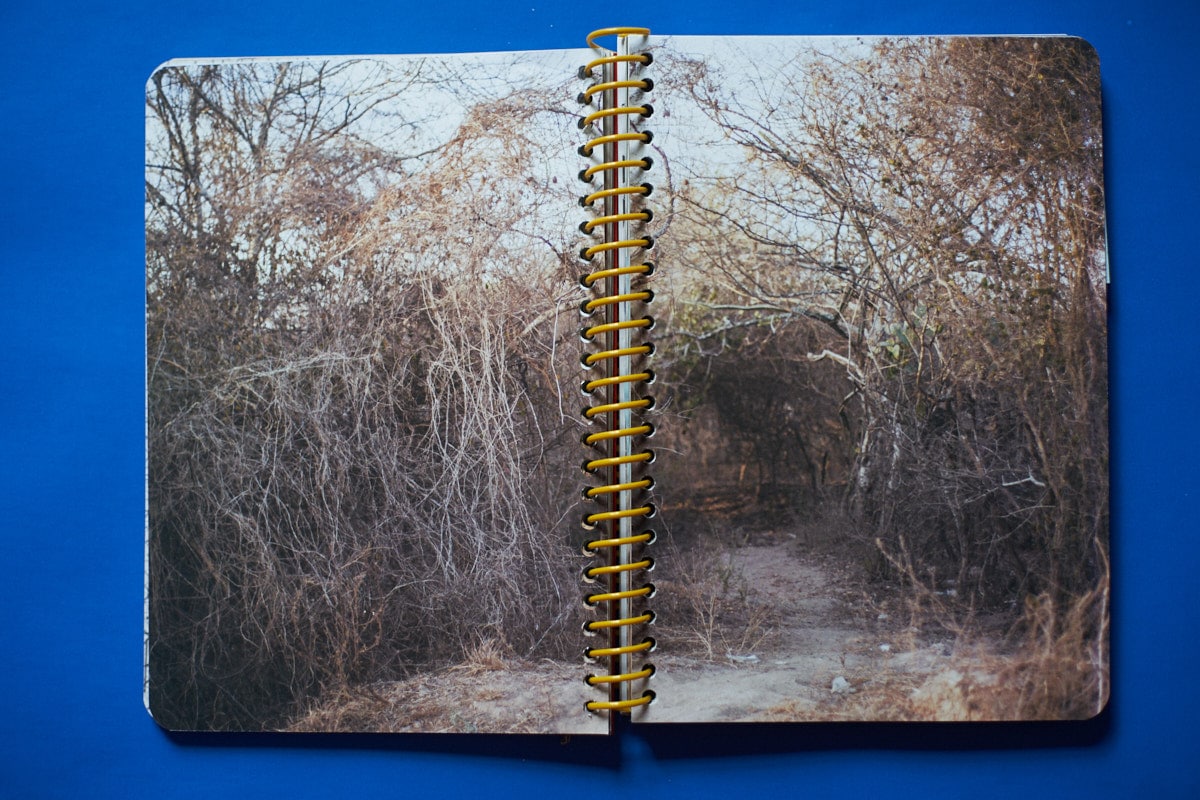

I worked from 2012 t0 2016 (then they threw up to make a park) in a very precarious House, with only male students. It was called Octubre Rojo. Is a reflection about how to survive in a community, what are the students in Mexico 50 years after Tlatelolco. Also, to talk about education, about the young death that exists through crime. Also about the death of the countryside. In the countryside, there is not work anymore.

This house had a very bad reputation, it was poverty. Poverty annoys. It was downtown, they always wanted it not to be visible. They were young children of farmers, fishermen, who survive as they can to study at the university.

Eunice Adorno – Casa Estudiantil Octubre Rojo

How did you get to this story?

My dad was part of the student movement, he was a very young student who was disenchanted with how it is a repression of a great movement. That feeling was always in my house, those anecdotes of the dirty war, fear, the feeling that the students were coming. I always had a very intimate question. I feel that it influenced a lot in the way of being and the way of seeing the world of my father.

Doing this social project on this site was, for me, very special. A student house is a place, a refuge, it is a kind of family home where students sleep. In our history, ’68 was a great blow to Mexican students. My father was also in the Plaza de Tlatelolco where many students died.

After that great movement, a liberal trend came, wanting a new man. When being repressed by the army, its importance also begins to be in other states of the Republic of Mexico that makes the students, in some way, also stimulate themselves, continue with a fight so that the university is democratized.

The idea was created that if you were a low-income student, you couldn’t go to university, because you had to rent a place to sleep if you came from a ranch. Then the student houses, united with the workers, were demanded by the government. It was about taking those abandoned spaces or abandoned hotels. Beyond sleeping, a self-managing organization is made: what are we going to eat? How are we going to organize ourselves to sleep? It is a symbolically very important thing in our country.

What ideas have you learned from this project?

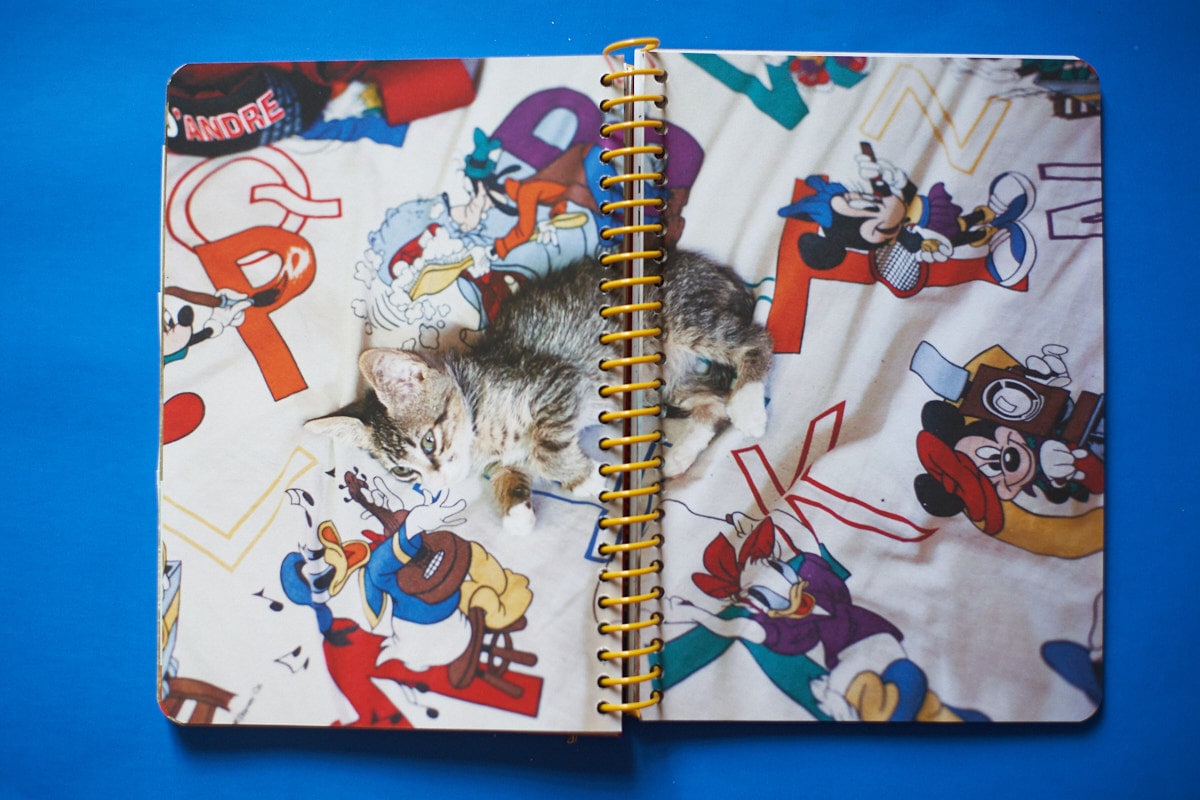

The construction of patriarchy, violence, orphanhood. They leave their ranches because there is nothing. After all, life in the countryside is very difficult, there are super radical climates. I think I will always remember this resistance. To resist is also do it in the face of poverty, in the face of many difficult factors, and even so they continued studying. That will always be there. Being able to go to very desolate, lonely places in Sinaloa. Feeling somehow safe with them, we made great empathy and great friendships there.

There is a whole community working there. Many of them went to the project presentation, now I am handing out books, trying to understand a publication when a project ends and is having a life of its own.

You had previously published Mujeres Flores, a study on the daily lives of Mennonite women from Nuevo Ideal and La Onda, two communities in Mexico. You won the Fernando Benítez National Prize for Culture in 2010. Would you say that it includes a gender perspective?

Mujeres Flores made them call me to do work on women, Octubre Rojo is also a look at masculinity.

In Desandar you have also worked with the history. Specifically with files, fragments, documents to reconstruct the stories of women of the Mexican Liberal Party. How did it come about?

Somehow I was interested in finding the archive of pre-revolutionary women and how these women, their speeches, their professions, are trapped in institutional archives where there is no classification of them. All the archives are always directed to men, it is very interesting how this history of struggle in the revolution is trapped in this institutional thing and remains totally in the documents. That is another search that I have with them. It led me to reflect on other forms of representation, how to look for other languages, installation, video, the plastic arts.