Even the walls will shout our rage

In 2019, Mexico was shaken by protests: women tired of the State’s ineffectiveness took to the streets to demand justice in cases of femicide and gender-based violence. In these marches, many scratched walls and monuments with feminist slogans. Diana Cano began to record them and realized that, shortly after the graffiti was painted, the authorities sent people to erase all the graffiti. That is how La Urgencia de Borrar and Borré las Paredes de las Pintas were born: two projects in which the photographer tries to preserve those words’ memory (and the power).

By Marcela Vallejo

“Ni una menos, ni una muerta más” (Not one less, not one more dead) is the verse that gave rise to the feminist slogan #niunamenos. It was written by the poet from Ciudad Juárez, Susana Chavez, who in 2011 was raped and murdered in her city. She did not get to see how the rest of us would shout this slogan throughout the length and breadth of our America. Her feminicide, like many others, has not yet been recognized as such by the Mexican State. In that country, on June 3, 2015, the first march was held with the slogan Ni una menos (Not one less).

Stories like that have populated the daily life of Mexico for years. In the last decade, the difference has been that women have begun to mobilize and demonstrate massively against these violent acts. Their demands have led to great advances and recognition at the legal and constitutional levels, but the numbers continue to grow. According to the National Observatory of Feminicides in Mexico, seven women were murdered daily in 2014. By 2023 that figure will reach 11 every day.

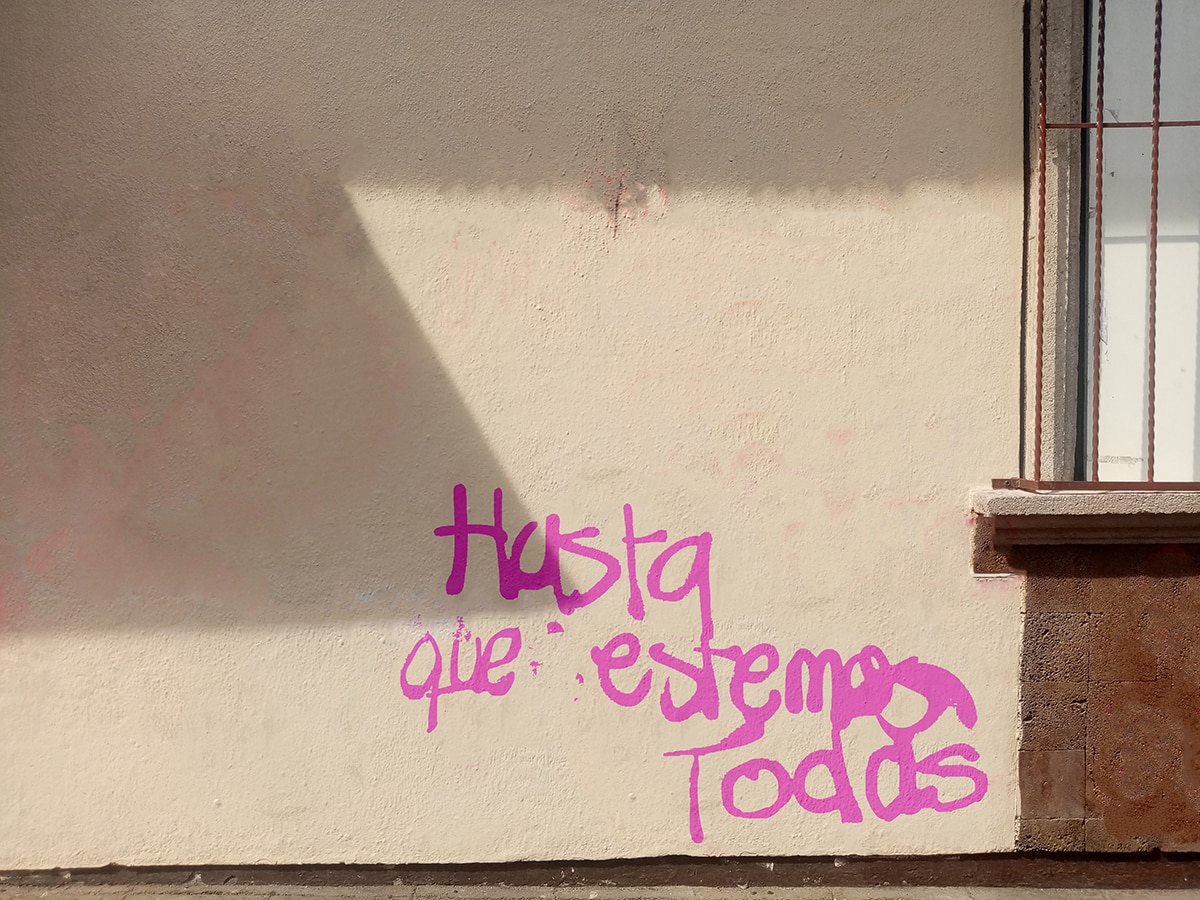

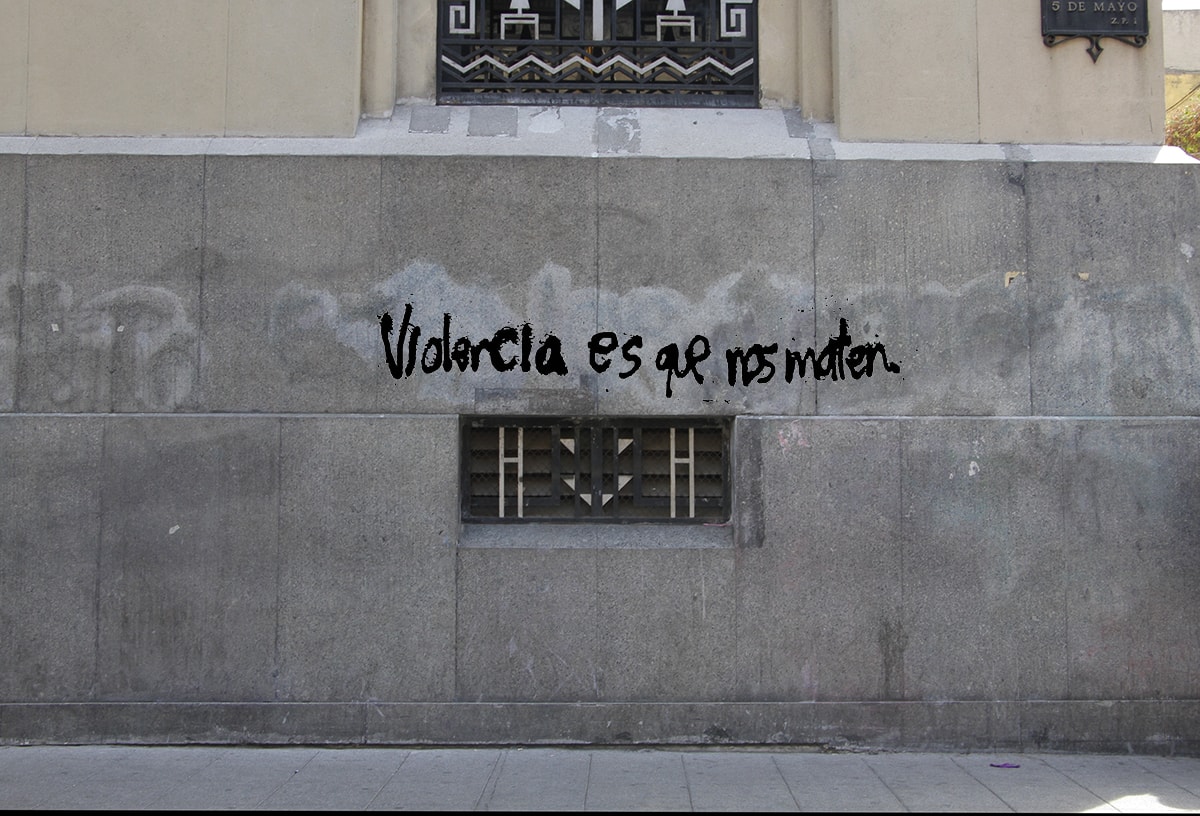

Situations like this are what has led many to protest. On August 12, 2019, a huge demonstration of women took to the streets of Mexico City. In their wake were a trail of pink and violet frost, graffiti on walls, broken windows and doors, and the echo of their voices demanding justice. In previous days there had been another case of sexual violence committed by police officers, this time against a young minor.

The women’s fury was felt when they learned that even though several days had passed after the incident, the police officers responsible had still not been charged and were still in their posts. The mobilization continued, and with each demonstration, more and more graffiti appeared on the walls.

The practice is not new and was not born in that week of August. But it intensified, and at the same time, the indignant responses of the authorities, the media, and the most conservative voices of opinion were felt by women. “Those are not the forms” was one of the most used expressions to criticize the graffiti on walls, doors, windows, and monuments. Many of these graffiti disappeared in the following days. With layers of paint, they removed what many called “stains.”

Seeing how quickly this happened led Mexican photographer Diana Cano to record the before and after: the pristine wall and the scratched wall. Two projects have emerged from this initiative, one still in progress and entitled La Urgencia de Borrar and the second, with which Diana edited a photobook called Borré las paredes de las pintas.

It is, in the words of its author, “a project that tries to reflect on the immediate erasure of graffiti in the public space—thinking from the emergency of feminicide and gender violence in Mexico. I find it a very violent fact that the next day or a few hours after the march, the cleaning staff arrives to remove all the denunciations and slogans. I erased the graffiti on the walls has more to do with the recovery of this visual memory that is erased.”

Thus, the two works have different objectives, although they arise from the same situation, and both reflect on the action of erasing. Diana affirms that “erasing has to do with a political positioning, that is, what we want to enter and what we don’t want to enter the discussion. I take up the idea of erasing under this idea of silencing legitimate protests regarding our security, laws, injustice, and many things we have been demanding.”

The reading of many social sectors against graffiti is that they delegitimize women’s protests. By not following the institutional channels, the message is “in the wrong place.” And that was the justification for criminalizing those who demonstrated. “But we know that the graffiti,” says Diana, “are instruments. From an ineffectiveness and deafness on the State’s part, these actions activate and make the demand possible.” In the case of her book, she changes the way of understanding erasure by removing the walls; This no longer becomes a “tool for silencing protest but a strategy for the visibility of demands.”

For Diana, the treatment given to the protest is the macro reflection of what happens when state agents must address gender-based violence. “When a woman is raped or when a person is raped and tries to approach these instances, we are almost always received in the same way: we are judged, we are questioned about how we were dressed, what we were doing, what time we were in the street. When we massively protest in the streets, they try to change the discourse, making us believe that many of these demands are unimportant or that we are exaggerating.”

Taking to the streets in protest, going out to shout for justice, and scratching walls is also a way of appropriating a space not designed for women: public space. If something happens to us in the streets, we are the first ones responsible for “being alone,” which is generally equivalent to being without a man.

“These are things that we have been learning socially and culturally,” Diana points out. “When we occupy public space alone, it seems synonymous with availability. The protest also concerns a legitimate claim to occupy the public road to defend our rights.”