Fire-wounded territories

Open Fire is a multimedia work that powerfully evokes the drama of forest fires in the Amazon. Its creator, Brazilian photographer, and activist Marilene Ribeiro takes analog photos of natural landscapes, burns the film originals with a lighter, and scans the result. The materiality of her images impacts the viewer more than any reportage or statistic could. And that is what she seeks: her work is a call to action.

By Alonso Almenara

Marilene Ribeiro will never forget the ” Day of Fire.” On August 10, 2019, a few months after President Jair Bolsonaro took office, Brazil’s most powerful landowners and farmers decided to set fire to the world’s largest rainforest systematically. The damage was so drastic that residents of Sao Paulo, a city 2,000 kilometers from the epicenter of the fires, watched the smoke from the forest turn day into night.

“It was a very explicit demonstration of violence,” recalls the photographer. “Four days after the fires started in the Amazon, I, who was in Belo Horizonte, had to travel to present a work in Rondônia. I couldn’t fly because of the smoke: all the airports were closed. It was a very aggressive thing to do and also a show of power. The businessmen told us: ‘We know that nothing will happen to us because the president is with us'”.

The following year, this ecological cataclysm was surpassed by a new record number of fires in the Amazon: 3,358 were registered in a single day, three times more than during the “Day of Fire.” A cycle of destruction that, as Ribeiro points out, does not stop no matter how many images of devastated nature reach the world’s television news.

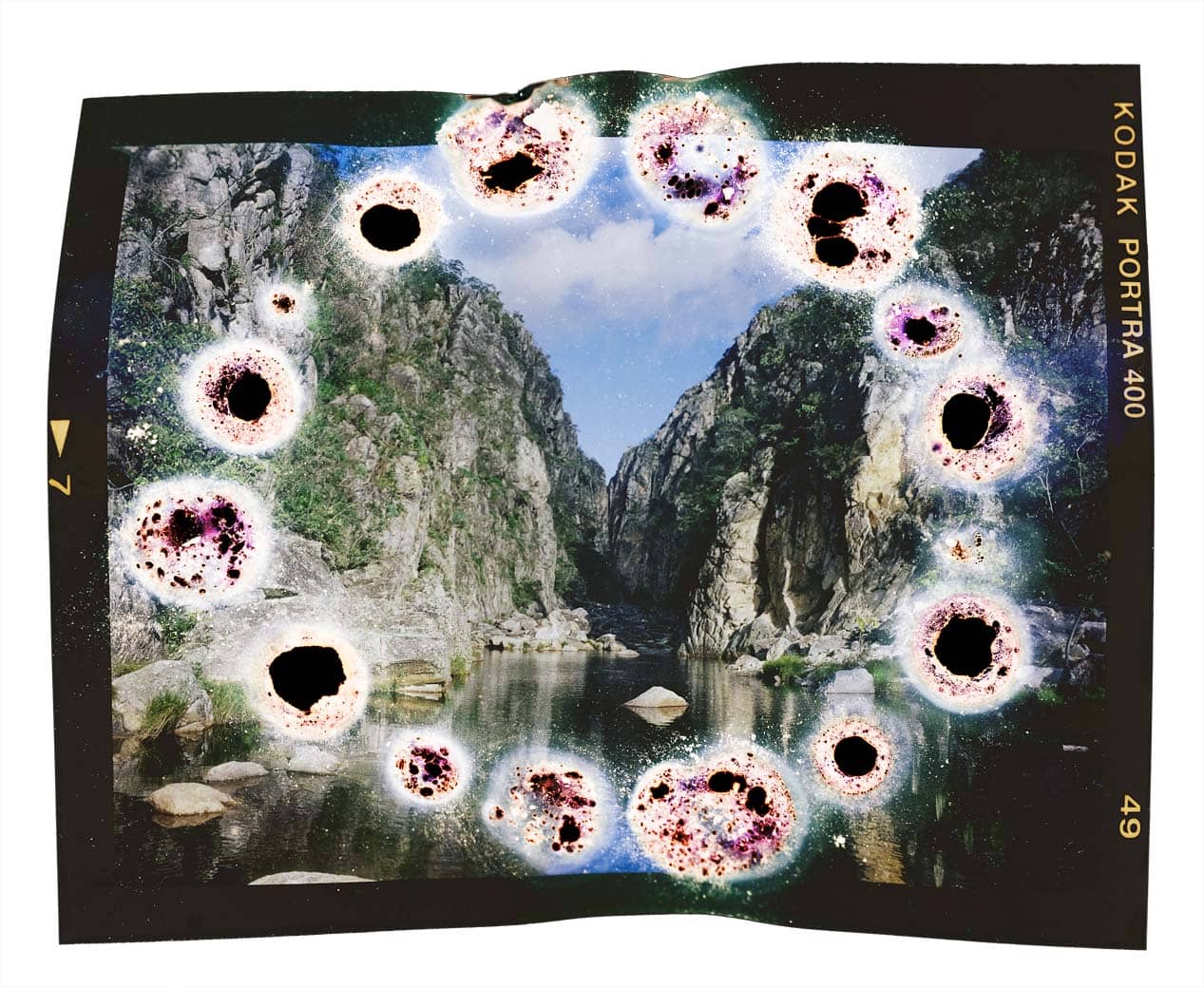

Dealing with this situation seems impossible. But that is what Ribeiro set out to do in the Open Fire project, a multimedia artwork in which photographic images of natural landscapes are intervened with fire, text, sound, and video. Winner of the Marc Ferrez Photography Award from Brazil’s National Arts Foundation, this work is currently on display at The Royal Geographic Society’s Playing with Wildfire exhibition in London. It was also selected last year to be exhibited at the Liverpool Biennial of Photography. A website shows the material virtually for those who cannot attend these events. The platform combines Ribeiro’s images of nature wounded by the fire with narrations recorded by the artist herself and texts made from news fragments, her writings, and social media posts.

“What interests me is that we stop being mere spectators of this horrendous reality and start acting, each in our way,” says the Brazilian photographer and activist. “We can be protagonists of what is happening, demanding, for example, better public policies. If we change our way of interacting with nature, in the long run, this situation will improve.”

As part of the preparations for a new edition of ECO, our meeting of photographic collectives that this year will focus on ecologies, territories, and communities, we talked with the artist about this experience designed to encourage discussion around a problem that every year seriously affects natural and cultural spaces in Brazil. It is a visually striking work and a political bet in which the Brazilian photographer believes deeply. So deeply that she is willing to burn the film originals of her photographs to send the message.

How was the Open Fire project born?

As an artist, I have always been interested in raising issues or perspectives that I consider politically influential, which have to do with the environment and the relationship of human beings with nature. In fact, I have dealt with the subject of forest fires in previous works; I am very interested in them because in Brazil fires have a very strong political role. Most of these fires, mainly those that occur in the Amazon, are caused by human beings to gain ground in the forest. They happen every year and damage the natural areas until they eventually have no reason to be conservation sites since they have lost their biodiversity.

In this way, businesses can be started in areas that had been protected, such as agriculture, cattle ranching, or mining ventures. And since it is always challenging to determine who started the fire, fire has become a straightforward weapon. Just start it and let the violence happen.

“Brazilian businessmen today do the same thing the conquistadors did: they use fire to destroy the houses of indigenous communities, which are often built with flammable materials such as wood and dry leaves because that is what they have at hand. Fire is used to destroy, create terror, force people to leave their homes in terror, and then kill them.”

Esto viene pasando en Brasil desde hace mucho tiempo: es como una estrategia de guerra. Una guerra de ocupación de territorios. Esto ocurre además, muchas veces, en situaciones de conflicto relacionadas con demandas de los pueblos indígenas para que éstas tierras sean reconocidas como áreas originarias. Se trata entonces de un antagonismo que tiene una carga histórica muy grande, que se remonta a la violencia ejercida por los españoles y los portugueses con respecto a las comunidades tradicionales vivían en estas zonas antes de la conquista. Y los empresarios brasileños de hoy hacen lo mismo que hacían los conquistadores: utilizan el fuego para destruir las casas de las comunidades indígenas, que muchas veces están construidas con materiales inflamables como madera y hojas secas, porque es lo que tienen a la mano. El fuego es usado para destruir, para crear terror, para obligar a las personas a salir despavoridas de sus casas, y luego matarlas. Es una situación específica, histórica, política, de violencia con el uso del fuego.

That happens apart from natural fires. However, these other fires, not caused by humans, are also a growing danger, right?

Indeed, with global warming and the droughts we are experiencing, these ecosystems are becoming much more vulnerable to fire, whether natural or not. That is, not only is it easier to damage them, but the fire of any origin often becomes uncontrollable and more dangerous. That happens not only in Brazil but all over the world. Last year, for example, there were very destructive fires in Spain, California, and British Columbia, Canada.

Shortly before that, it happened in Australia, and in Brazil, there was a powerful fire in 2020 and 2021 in Pantanal, a plain near Paraguay. That region is famous worldwide for its mega biodiversity. And it was arson because many cattle ranches in the area wanted to expand even more.

But the problem is that because there was an extreme drought, control was lost, and it was a horrific situation. I have never seen anything so substantial, and the images went around the world. Because in the Amazon, there are fires every year, but this was the first time that the pictures were shown on television: you could see videos of jaguars and monkeys burned. It was a very horrible thing. And the territory affected was vast: an area of forest equivalent to half of Switzerland burned in nine months. Nine months. It was challenging to put out the fire because of the drought.

I understand that, in addition to climate change, another factor has impacted the increase of fires in the Brazilian Amazon: the environmental policies of Jair Bolsonaro. Is this so, and what is the current situation? Has this trend been reversed with Lula in power?

There was indeed an increase in fires during Bolsonaro’s time in power. While part of that increase is due to climate change, it is clear that the former president’s discourse has also been an indirect stimulus. Bolsonaro often declared no interest in nature and promoted mining, cattle ranching, and soybean cultivation in these areas. He said his project was to transform the Amazon into an economic power in terms of extractives but not in terms of biodiversity or cultural wealth. In other words, he thought the same way as those in the agribusiness sector who supported him.

These entrepreneurs are only interested in growing their land to have more cattle, production, exports, and money. They don’t care if to do so. They destroy nature or the territories of traditional populations who live from more sustainable activities such as chestnut production or hunting. And it was precisely because of this kind of thinking that I started to imagine the Open Fire project in 2019.

Bolsonaro was elected in 2018 but began his term in January 2019. That year, when the fire season arrived, which everyone knows, and goes from July to September because they are the driest months, something unprecedented and very worrying happened. The government itself encouraged the fires. That’s where the title of my work comes from, “Open Fire,” which in English has the double meaning of “open fire” and “shoot.” On the one hand, it is the idea of burning everything, but it also refers to war, shooting and killing without mercy. And that is what is happening in Brazil. It is a cycle, something that happens every year. With Bolsonaro, it was worse, but it kept happening.

“What interested me with this work was the possibility of starting a dialogue with society about what we have lost over the years with this cycle of violence. I wanted to emphasize the idea that these are irreversible changes. The question was then: how to account for the magnitude of the destruction? How to represent that which for future generations will have ceased to exist?”

What is the population’s response?

Commonly the newscasts report forest fires in July and August. At that time, everyone is shocked and talks about it, but the season passes, everyone forgets about it, and the following year it starts again. And it does not happen only in the Amazon. I talk about Amazon because it is a name that everyone knows internationally, but the same thing happens with all Brazilian ecosystems.

Let’s talk about the photographic treatment you give to this subject. Could you describe your methodology?

What interested me with this work was the possibility of starting a dialogue with society about what we have lost over the years with this cycle of violence. I wanted to emphasize the idea that these are irreversible changes. The question was then: how to account for the magnitude of the destruction, how to represent that which for future generations will no longer exist?

Using statistics, for example, seemed very abstract to me. Talking about 10,000 soccer fields burned doesn’t necessarily go far; it’s hard to imagine. You know it’s gigantic, but it doesn’t impact you as much as the materiality of the destruction. So I came up with the idea of working directly with that materiality, destroying the photographic representation of natural landscapes.

To achieve this, I work with a medium format film, a size large enough to expose it to fire and control the result to some extent but also small enough to make the damage visible. Anyway, I must say that fire is a highly unpredictable element. It gets out of control very quickly, as it happened, in fact, in the Pantanal crisis. So my idea was to work in a way that would allow me to encapsulate those meanings of destruction, lack of control, and irreversibility, as well as the impossibility of accessing those natural landscapes in the future.

I want to end this interview by discussing your experience as an artist living between South America and Europe. Does this condition inform your work in any way?

I am Brazilian but have lived effectively between Brazil and England for a long time. It’s a kind of nomadic existence that I’m interested in maintaining because my idea is always to use my perspective from Brazil to talk about global issues. This is the case of forest fires or the problems associated with hydroelectric dams that I dealt with in previous work. Both have to do with climate change, which affects us all. I speak as a Brazilian, then, but I make great efforts to bring this message to the global north because people here influence too much what happens in Latin America.