Ghosts of the Great Depression

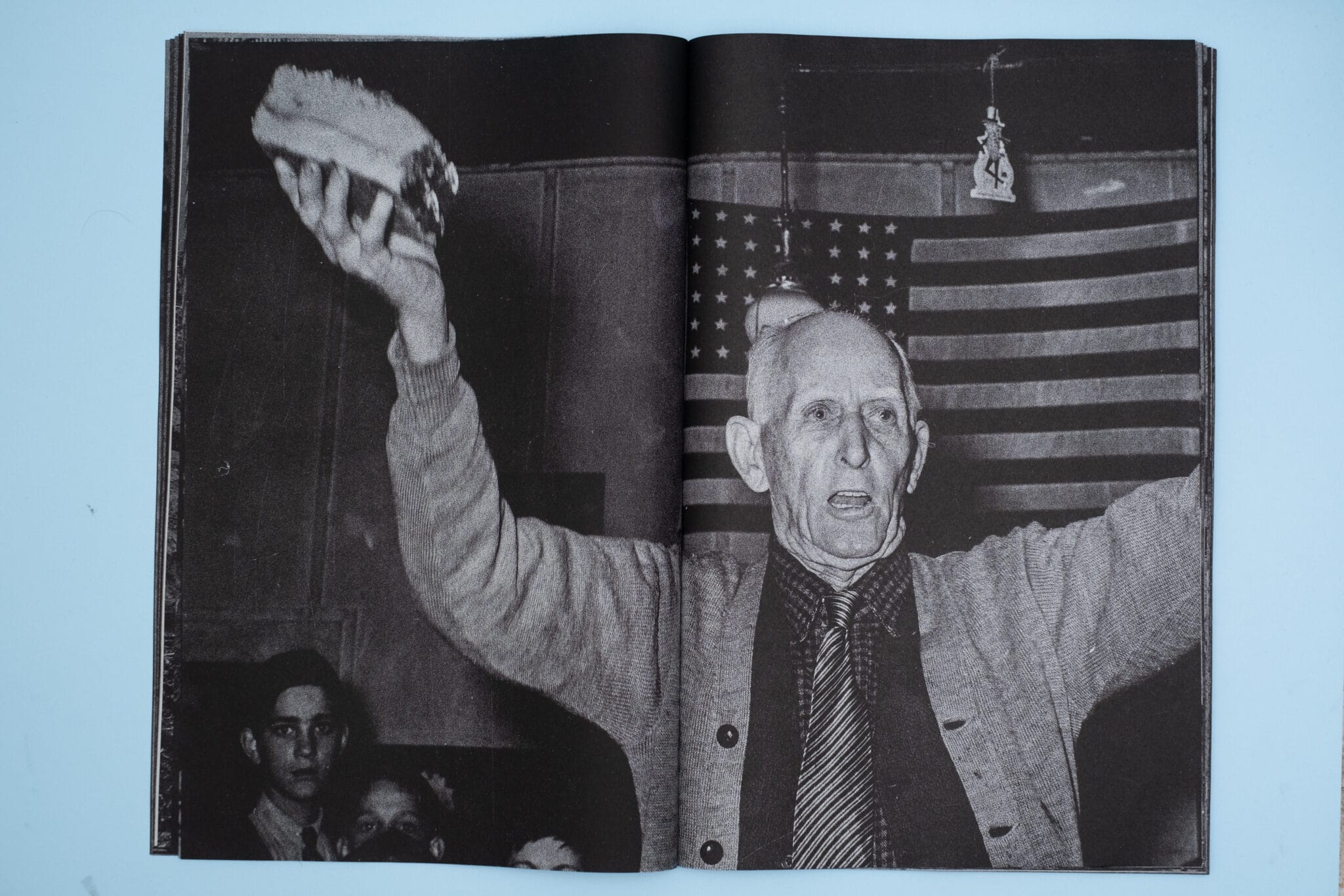

In Omen, a photo book edited by Jorge Panchoaga and León Muñoz Santini, the Crack of ’29 and the Dust Bowl become mirror images of the current crisis of American society. Made with materials from the Farm Security Administration’s mythical photography program, this combative book subverts, from the reframing and editing work, the ordinary senses of American identity that this set of images helped to cement.

By Alonso Almenara

The word omen -presagio, in Spanish- appears in the description of a dust storm in The Grapes of Wrath, John Steibeck’s great novel about the agrarian crisis of the 1930s in the United States. For León Muñoz Santini, that image stuck in his memory. He recalled it years later while excavating an archive of 20,000 negatives from the Farm Security Administration’s photography program (1935-1944) housed in the New York Public Library. Under the Mexican editor’s gaze, the tensions evoked by Steinbeck – and documented in that repository made up of thousands of portraits of impoverished farmers during the Great Depression – resonated with the discontents of Trump’s America.

Muñoz Santini is not the first person to note parallels between America’s past and present. Historian Karen Kruse Thomas has observed that the Dust Bowl of the 1930s is the closest antecedent to the current covid-19 pandemic. Like a harbinger of our world, it was a crisis that occurred suddenly, caused alarming respiratory distress, and spread with the rapidity of a virus.

Kruse Thomas explains that the phenomenon “was caused by farmers using new technology to break up the hardened soil of the Great Plains and open it to cash crop agriculture.” Because of the drought, the soil turned to fine dust absorbed by ‘black blizzards’ – “massive, unpredictable windstorms that derailed trains, choked hapless commuters, and infiltrated every crevice of homes and buildings.” As a result, half a million Americans lost their homes, and some 7,000 died of pneumonia.

In the words of historian Donald Worster, that humanitarian crisis revealed the “fundamental weaknesses” of American society but also offered “a reason and an opportunity for substantial reform.” Created by the Roosevelt administration as part of the New Deal, the Farm Security Administration was the agency that reshaped the crisis-ravaged rural sector. Today it is remembered mainly for the vast photographic archive it produced between 1935 and 1944: about twenty photographers were called upon to portray what was happening in the countryside. Among them were Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, and Roy Stryker, who directed the program.

It is not difficult to understand why this initiative is considered one of the milestones of modern documentary photography. The set includes an image like Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, an iconic portrait that captures the despair of Florence Owens Thompson and her children in a camp for farmers who lost their crops. The expressiveness of Lange’s work does not leave Muñoz Santini indifferent. But what interests him is to dissociate these photos from the hegemonic narrative built around them: mainly about triumph against adversity, division, and catastrophe in American society. A report that not only contrasts with the country’s legacy of violence outside its borders: it also invisibilizes and excludes its citizens, discarding some of them as valid subjects of the photographs.

That is why, for Muñoz Santini, the most exciting part of the archive occurred in the margins, corners, and areas where the main subject is lost from sight, and the unexpected happens. Nothing now prevented him from appropriating the archive, reframing it, and using it against its original function to tell a different story of the United States.

Getting into the kitchen through the back door

León Muñoz Santini and Jorge Panchoaga met in 2019 when they were invited by the Centro de Fotografía de Montevideo (cdF) to lead an editing workshop at the EN CMYK meeting. Both are founders of influential imprints in the Latin American photobook scene: Muñoz runs Gato Negro in Mexico, and Panchoaga, the publishing house Croma in Colombia. Working with high school students, they experimented for ten hours called Su búsqueda no produjo resultados, made with images from the cdF’s photo library. The book is unique in that it not only explores the archive’s content but interrogates its gaps critically, contrasting them with the history of Uruguay.

“In our searches, we were surprised that certain words yielded no results,” Panchoaga recalls. “No terms like ‘migration,’ ‘tango’ or ‘prostitutes’ appear. Nor did ‘missing persons’, even though Uruguay had a dictatorship that disappeared many people.”

Jorge Panchoaga: “We decided to sneak into the kitchen through the back door and eat what was in the fridge. We feel we have every right. They have set up dictators, intervened in societies, and participated in the extermination of populations. What interested us was to intervene symbolically in U.S. history, pointing out what is in the back, what seems to be hidden but is there, and that also consolidates today’s world.”

Panchoaga explains that questions and methodologies emerged from that workshop that remain active in Omen. Phantasmagoria at the Farm Security Administration (1935-1944), his second book edited with Muñoz Santini: How do institutions remember? What are they interested in placing? And to what extent do they influence collective memory?

“The original intention was to repeat the procedure of Su búsqueda no produjo resultados, but with more time, and using material from another Latin American archive,” says Muñoz Santini. “We tried. Jorge tried at the Biblioteca Pública Piloto in Medellín, and I tried at the Fototeca Nacional in Mexico and the Museo Archivo de Fotografía; we were completely ignored. For the Mexican editor, “that speaks of another of Latin America’s backwardness: the levels of accessibility and digitization of archives in general, and photographic archives in particular, are not ideal.”

The New York Public Library houses a fraction of the negatives produced by the Farm Security Administration’s photography program. The primary collection, ten times larger, is housed at the Library of Congress. But this repository is still an enormous universe, and one of its great attractions is that the photos have been scanned in high resolution and placed on the institution’s web page, free of rights.

For Muñoz Santini, “there are interesting and unintended consequences of reaching this archive and touching such a gringo history from Latin America. And the fact is that it has generally been the other way around. Panchoaga is emphatic: “We decided to go into the kitchen through the back door and eat what was in the fridge. We feel we have every right. They have set up dictators, intervened in societies, and participated in the extermination of populations. We were interested in symbolically intervening in American history, pointing out what’s in the back, what seems hidden but is there, and that somehow also consolidates today’s world.”

Making sense of the catastrophe

Panchoaga and Muñoz Santini acknowledge that the book has limited circulation so far. The first edition, which appeared late last year in Mexico, is already out of print. A second edition, in a slightly smaller format, was published by Penumbra Foundation in New York. The third edition is being printed and includes adjustments and a handful of additional pages. They have been small print runs, but this will be corrected by the fourth edition, which will appear next year from the Spanish imprint RM.

One of the most enthusiastic reactions to the project has come from the New York Public Library itself. The institution is preparing to launch a residency and fellowship program to put its photo library to work. “They told us that what we had done with Omen was precisely what they are looking for,” recalls Muñoz Santini.

One of the Library’s curators, Paloma Celis Carbajal, wrote a review of the book that is worth quoting at length:

“They carried out their excavations at home during the endless confusion of pandemic confinement. During those days, we all watched in horror as images appeared in the media showing the growing tensions and discontent in a society that seemed to be at its breaking point. Images of our current climate are evoked when we look at this collage: the endless cycle of abuse of African Americans by law enforcement; the suffering of the sick and disabled who have not been cared for by a failing healthcare system, and the growing poverty and precarity for many in this time of deep economic crisis. Despite all this, Omen, though bleak, gives me hope. After all, we can make sense of even the toughest moments in this country’s past. We can discover new approaches to interpreting our present through the eyes of others, which leads us to question our current path as we find ways to imagine a better one.”