How we are supposed to live

One day, Chilean Carolina Aguero saw a sign of a missing girl at a station. She phoned, and her mother answered the phone. Carolina learned that she was a lesbian girl who was missing and began to wonder how she was supposed to live without harassment and violence.

Carolina was born in Puerto Montt and trained at the ARCOS Professional Institute in Viña del Mar. She exhibited in solo and group shows while teaching classes and workshops at the Cultural Park and the University of Valparaiso. Between 2013 and 2014, Carolina was part of the Latin American Living Artists auction in Miami, USA. Last year she released a compilation of books: transgender boys, transformism, and lesbian girls.

Carolina Aguero

How did ‘The imperfect image: between your word and mine’ come about?

This project was born because I entered the bus terminal to travel to Santiago one day, and I found a poster of a girl missing for several months.

I phoned because I was surprised by the very masculine clothing. The mother told me that she didn’t know if her daughter had left or was murdered and that she was a lesbian. That was why her mother was so scared and worried. I asked myself: how important is my identity, or what can I do with my body for these things to happen? Of violence, of being afraid. We are a bit more open, even though it has been a few years. We are creating stronger bonds.

I started to think that it was crucial to have a testimony based on lesbian, transgender girls. I am also a lesbian.

Carolina Aguero

I live in Valparaíso, a diverse city where many people come from other regions. Many leave their areas because of their sexual conditions. I began to photograph these boys and girls, and I wondered why they had to hide their identity, not tell their parents, be afraid, and never go back to their region or city because of their sexual condition.

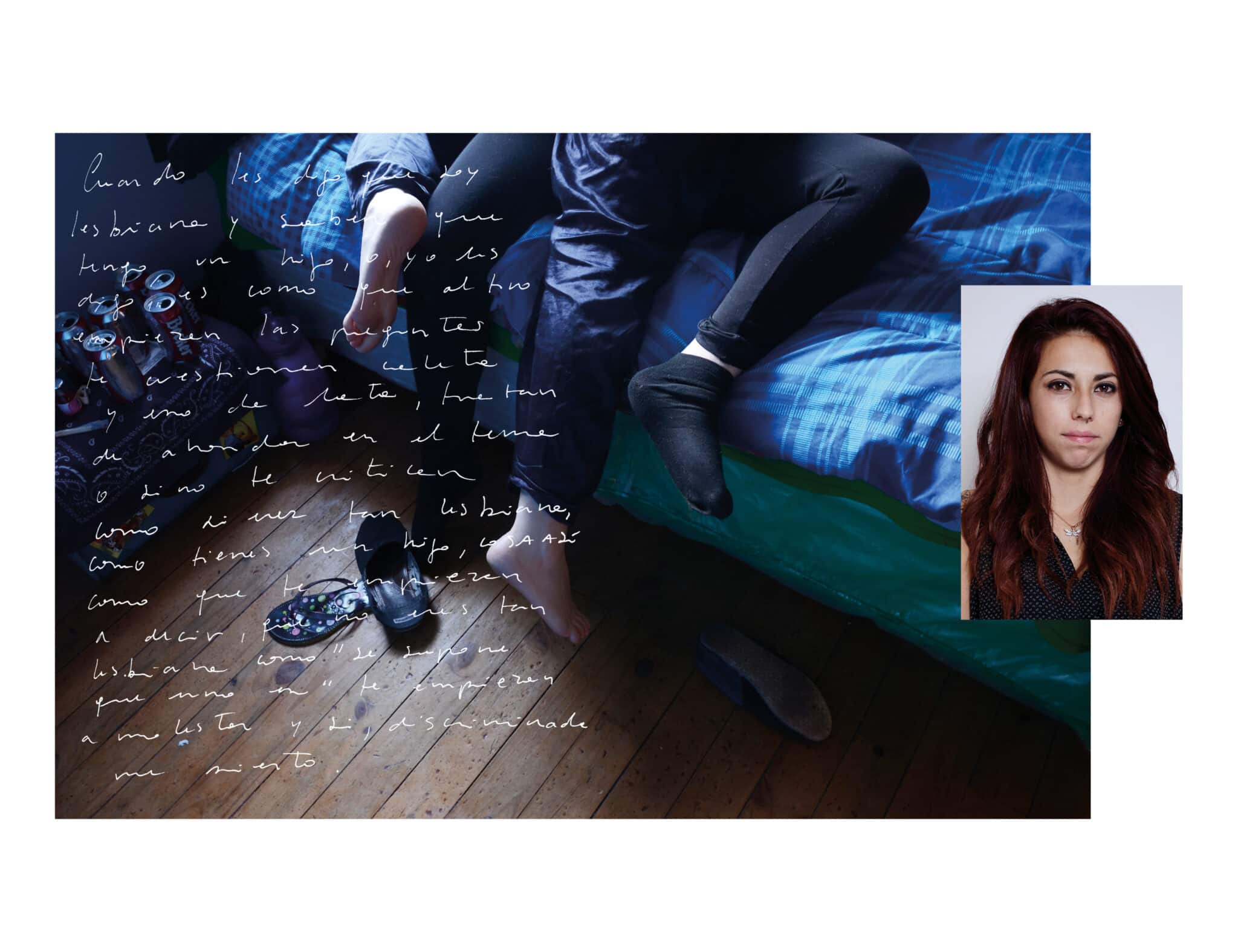

I decided to get close to some girls. I take the time to get to know the people I will document. I come to them, and I try to build trust. We become friends, and I start to look into their personal lives. My idea was first to portray their spaces and how lesbian couples lived. Then I rethought it from another point of view, from the hiding, the back, girls who, because of their working conditions (because they worked in childcare or a bank), could not say that they are lesbians because it generates prejudice.

I started to make portraits in the studio, and I proposed not to show their faces. Still, they left a writing testimony about how they were inserted into society and lived their sexuality or lesbian life. Another testimony also emerged, and I worked with the audiovisual. Some of them were interviewed: about how it was as a child until they grew up. The back has to do with hiding, having to be constantly afraid.

What surprised you the most?

A girl who, as a teenager, was very aware that she was a lesbian fell in love with a friend who was gay. She told me about the prejudices surrounding being a mom and a lesbian and how others questioned her about “how much of a lesbian she was.” In the end, stereotypes always emerge.

The second story that struck me was of another girl who, at 14 or 15, told her mother that she liked girls, and her mother attempted suicide and locked her up until she was 18.

I’m with the camera, and sometimes I interact; sometimes I’m just silent. The bond is intense: I am still in contact with some of them, and some have decided to be transgender. Talking about non-conformity makes a super-strong bond.

Is ’74 Nudos’ a series that talks about healing?

The project came up while traveling through Latin America. I had been embroidering for a while. I arrived in Peru and learned about the more decorative embroidery, about Jesus cards. I realized that there was a wave of violence from 2015 onwards.

I wondered how many times we have felt violated and afraid of the street. You can’t be late, because if you are late and a man wants to rape you, it’s your fault. The violence within the family is hidden, or the violence when you are psychologically abused. I began to realize that nobody wants to talk about these things. People were afraid to express themselves. I started to photograph my mother, friends, and close circle; I wanted to know what was happening to them and what they felt. I asked them for a phrase, and I began to embroider on their photographs based on that phrase.

There is a Latin saying about braids: when you have a lot of internal pains, you start to braid them to leave the pains in those braids. I started little by little. The testimony is super important: you talk about their lives and show their faces and pain.

The project started because a friend asked me if I could take a photo of a 12-year-old girl. I have never worked with minors, but her mother was going to accompany her. Her uncle had raped her.

’74 Nudos’ is named after the 74 femicides in Chile between 2018 and 2019. And the embroidery portrait is “an act of fixing the memory through needle and thread.”