Latin America is an overcrowded prison

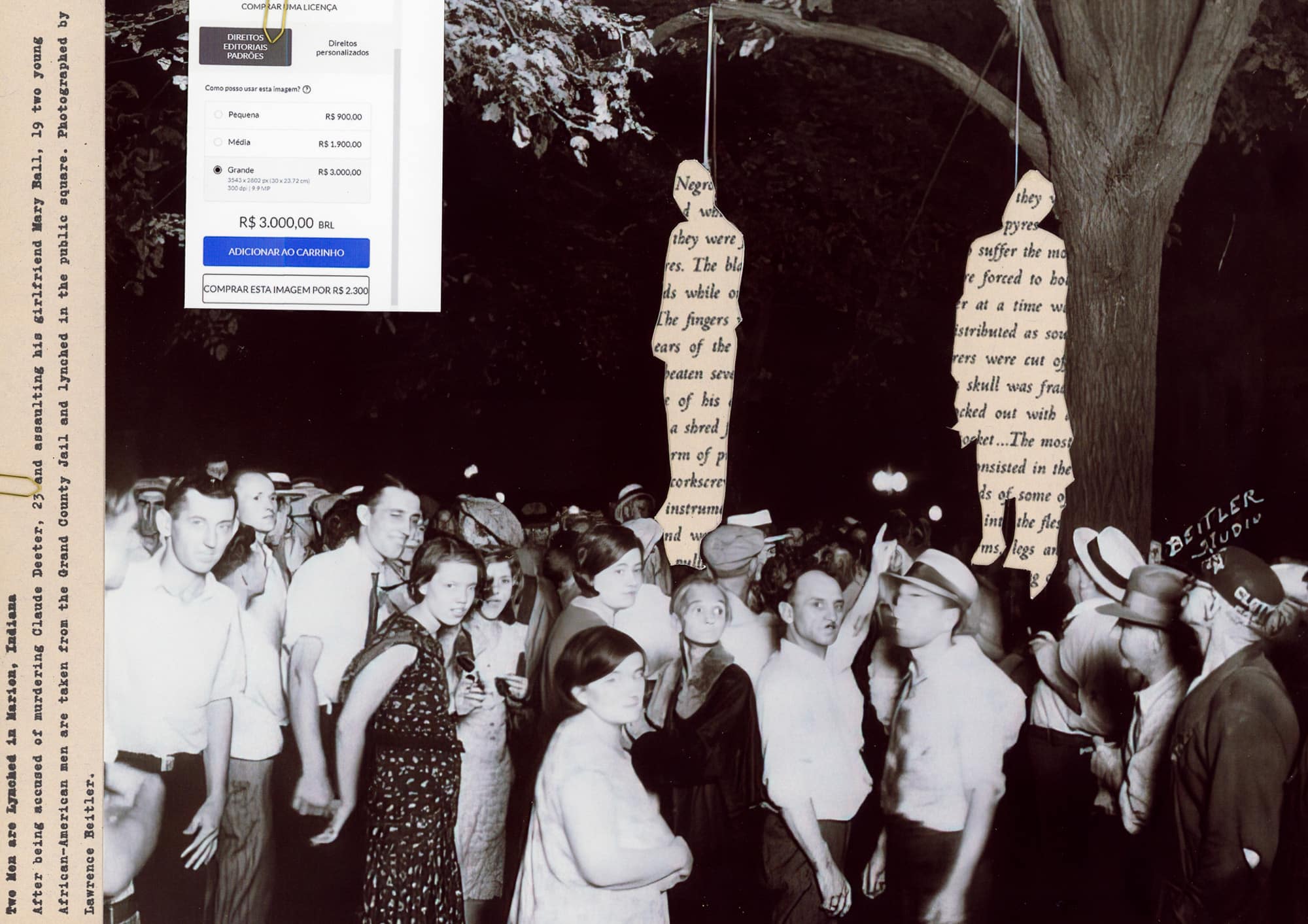

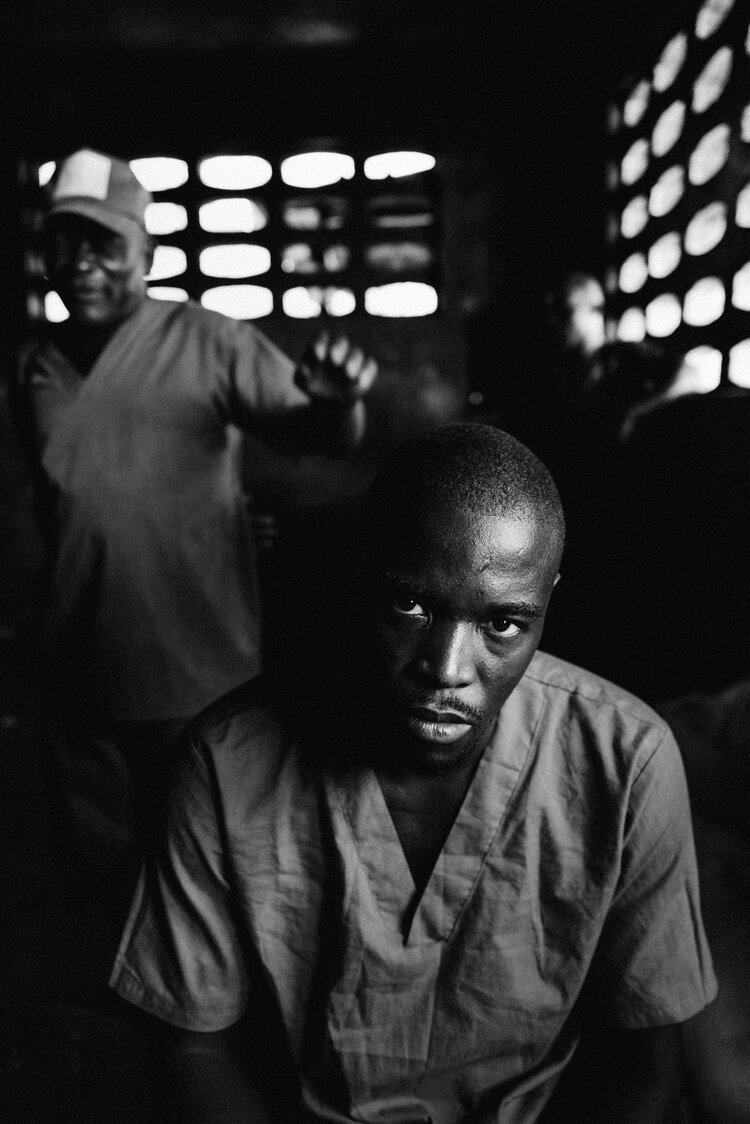

There is enough data to confirm the barbarism committed within the prison systems of almost every country in Latin America. Nevertheless, reports of torture, deaths, inmate health conditions, incarceration rates, and prison capacity continue to increase: since 2000, the prison population has grown by 74% in Central America and 200% in South America. To put a face to these figures and restore some humanity to the millions of people deprived of liberty and dignity, Brazilian photographers Thiago Dezan, Erick Dau, and Francisco Proner, members of the Farpa agency, visited 18 prisons throughout the continent. This is what they saw.

By Miguel Vilela | Photographs by Thiago Dezan, Erick Dau and Francisco Proner / Farpa

In addition to language and culture, there is an everyday reality throughout Latin America: the precariousness of prison systems and the brutality in treating prisoners. Except for Belize, Chile, Suriname, and some Caribbean islands, all Latin American countries have a prison capacity exceeding 100%. In Brazil, the largest country in the region and with the third-largest prison population globally, the occupancy rate is 143%. Of the 1,381 prison units, 276 have an occupancy rate of over 200%. In El Salvador, where the prison population has increased almost fivefold in the past 20 years, the occupancy rate is 237%. In Haiti, it’s 454%. In Bolivia, it’s 263%. In Paraguay, it’s 172%.

But these numbers, collected by the World Prison Brief website, fail to convey the horror of what happens inside these prisons. With this in mind, photographers Thiago Dezan, Erick Dau, and Francisco Proner, members of the Farpa agency, created the project “o Desse lado do muro” (On the Other Side of the Wall).

In a phone interview, Thiago Dezan explained that their motivation, along with their colleagues, was to carry out in-depth work that wouldn’t get lost among the thousands of daily stories that appear in newspapers. Above all, they also wanted to restore some humanity to the millions of prisoners, the vast majority of whom are incarcerated for drug-related offenses, condemned to a kind of death but forced, as Dezan recounts, “to continue in their bodies, living a life in filth, without food, without anything.”

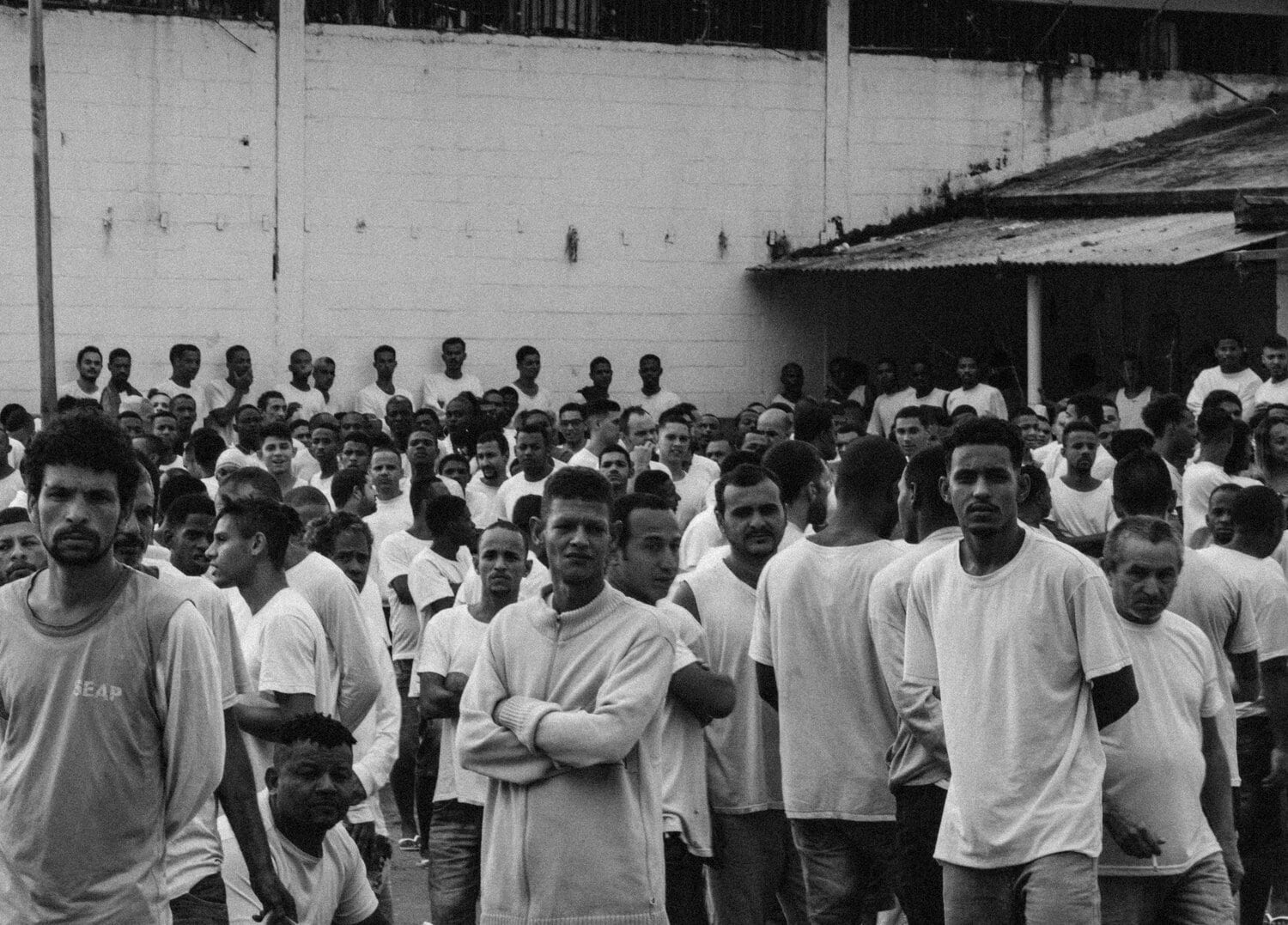

So far, the group has visited 18 prisons throughout Latin America, often following the work of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. The result is strangely similar images of people eager to be photographed so as not to be forgotten.

In the essay published on the agency’s website, the location in the photos is not indicated because it doesn’t matter: “It’s as if one prison ends and another begins. They are different countries, but as if all the prisons were one nation, where humanity no longer holds as much value.”

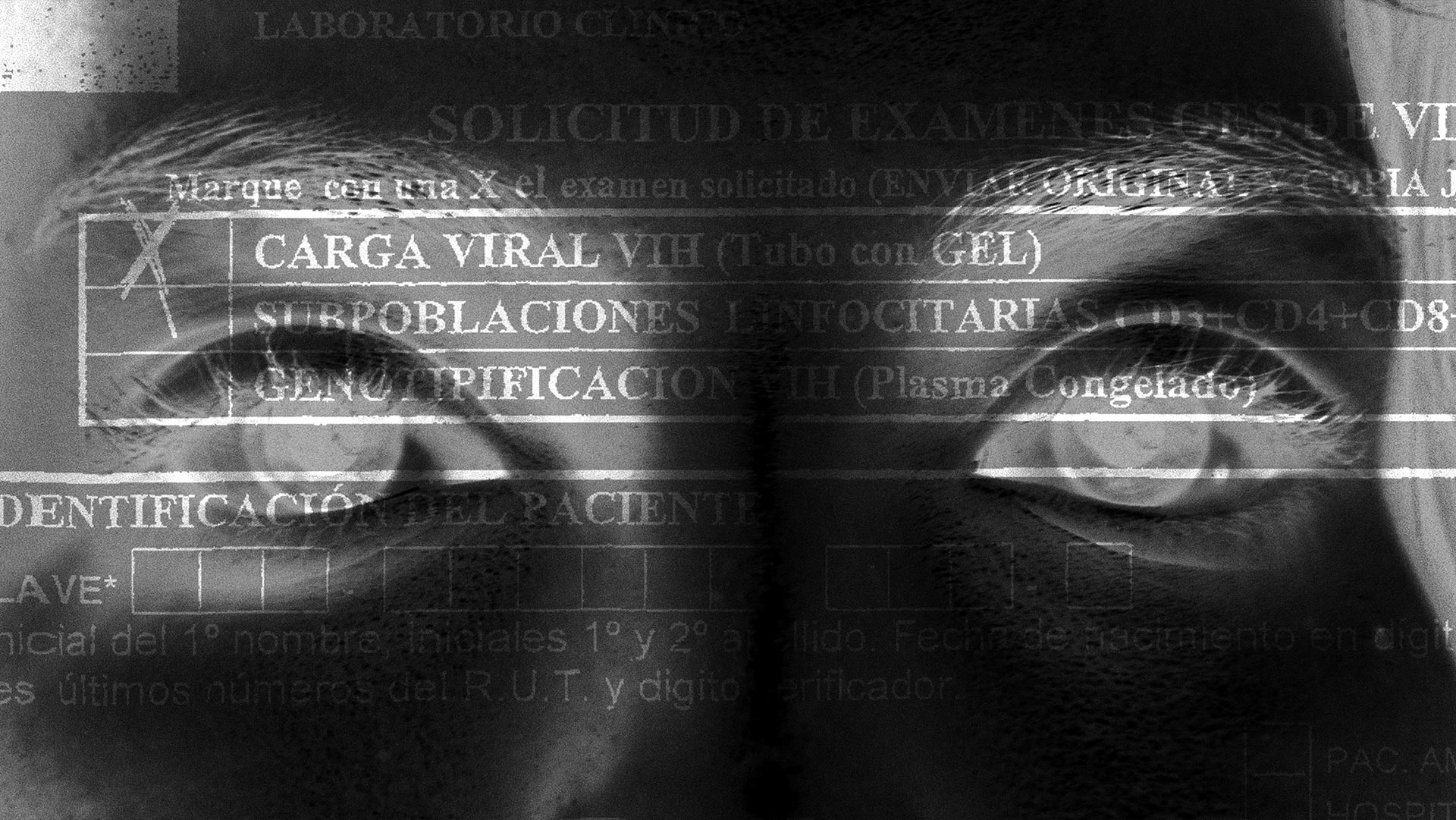

Thiago Dezan/Farpa

Francisco Proner/Farpa

“We decided to create this essay by blending photos from prisons in different locations because it was as if one was an extension of the other. There was no place we visited where we could say it was a model prison where people had access to work or education. It’s as if one prison ends and another begins. They are different countries, but all the prisons were one nation, where humanity no longer holds as much value.”

Thiago Dezan/Farpa

Francisco Proner/Farpa

Beyond daily news and sensationalism, how do you see photojournalism’s potential to improve this situation?

There is an excellent effort in documenting so people can feel some of the pain, suffering, and despair in this situation. It is very different to read a text or know information without having a visual representation of what that means compared to seeing an image of a hallway filled with injured or amputated people, without access to medical care, or with a damaged colostomy bag. I believe that creates a strong impact and moves people.

You present content that becomes harder for responsible authorities to question because it is something wholly exposed in front of you. Therefore, photography and video have the fundamental role of showing reality and making it undeniable. When you have photos, for example, of a cell with 100 people where only 20 can fit, and the prisoners have to weave their makeshift nets with plastic bags to sleep hanging over each other so as not to have to sleep on an unsanitary floor, those images surpass any legal description that a lawyer could make about the situation.

There is also the work of raising awareness in society, and through photos, it is easier to show the pain people feel and the lack of dignity with which they are being treated.

Thiago Dezan/Farpa

Is there a specific story that has marked you?

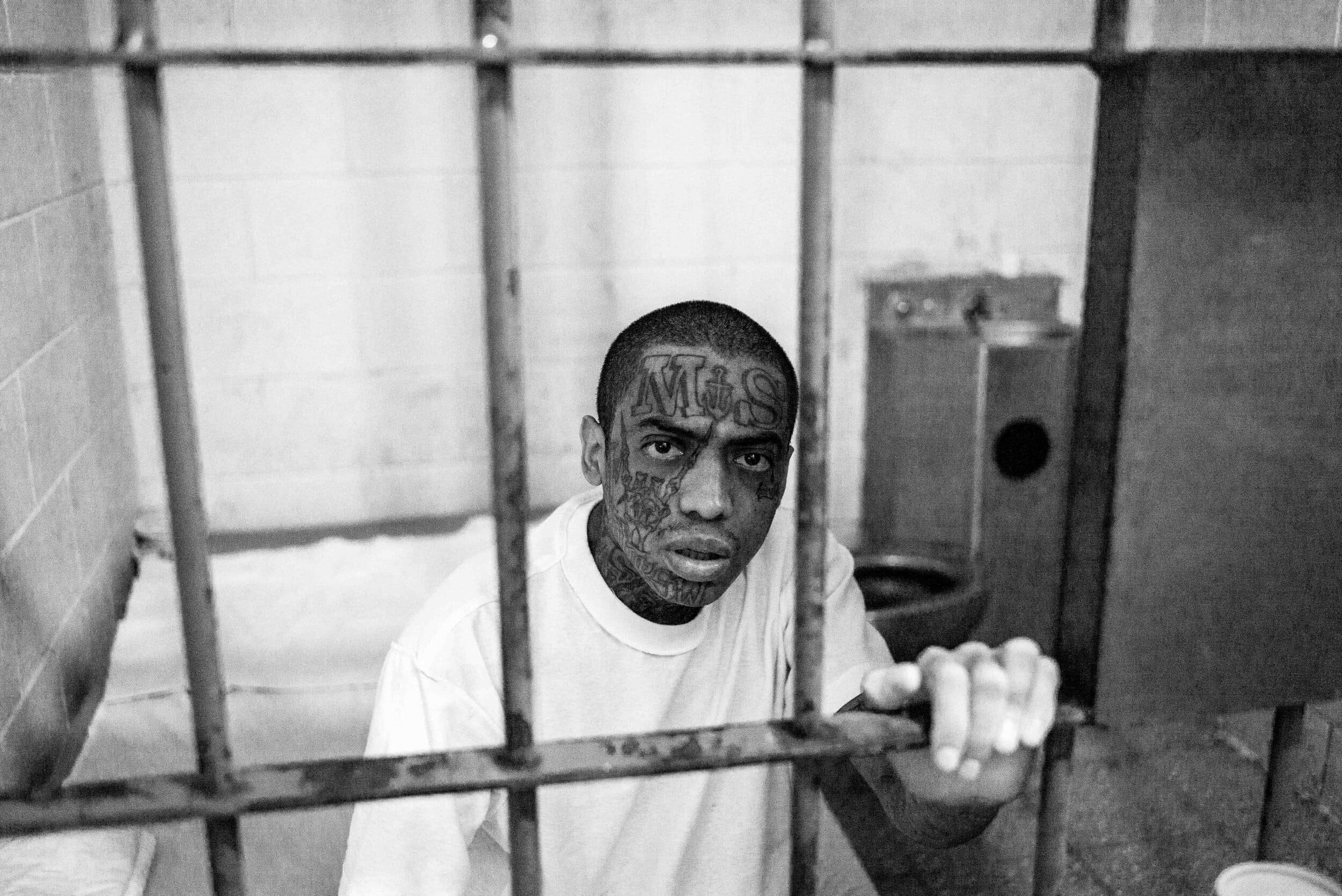

I visited five maximum-security prisons in El Salvador, which was very tough. When I went there in late 2019, they had gone five years without receiving any visits. So, neither their relatives nor their wives, mothers, or children, no one could see them. They didn’t know if they were alive, dead, sick, or okay.

Therefore, these people were pleased to have someone capture images because people want to be seen and remembered.

They told me, “It has been more than five years since anyone in my family saw me, so take a picture of me and put it wherever you want. Maybe someday someone can see me, look at my face, and remember me.”

Nobody wants to be forgotten, and that is something that hurts a lot. In addition to being in a situation of extreme discomfort, extreme lack of respect, and loss of dignity, the person also fades from people’s memories, and they start forgetting how you were, your face looked, your voice. Through these photos, we managed to show many people around the world the situation they were living in.

Thiago Dezan/Farpa

Francisco Proner/Farpa

“It is very different from knowing information without having a visual representation of what it means compared to seeing an image of a hallway filled with injured or amputated people, without access to medical care, or with a damaged colostomy bag. That creates a strong impact and moves people. You present content that becomes harder for authorities to question because it is something completely exposed in front of you.”

Is there anything you have learned in this process? Any idea or perspective that you had that changed?

We often take for granted the freedom to move, to go from one place to another, considering their innate rights. But when you see these people who have sunlight for one hour a week or who are cramped in a cell that measures two meters by one and a half, you begin to value the possibility of movement, taking a trip, going out, having a conversation with a friend, having access to pen and paper to write down your thoughts.

These things are taken away from incarcerated individuals and make us reflect on our lives.

There was a lot of talk about quarantine during the pandemic and how difficult it was to stay at home without being able to go out. But these people were already confined long before the pandemic. And not just for six months but for years and years, without any prospects of it changing.

That impacted me greatly. If you compare it, the experience of confinement seems like child’s play. These individuals don’t have the right to sunlight or to receive visitors. They don’t even have the right to exist. It’s like a form of almost a death penalty, but a death of your humanity: you still have to continue in your body, living a life in filth, without food, without anything.

I saw a person, for example, who, when you looked into their eyes, had a specific power and aggression in their face, which might have made you fearful if you saw them on the street. But inside a medical cell, they were utterly emaciated. You could see their bones protruding from their skin, almost dying from malnutrition. That is something that has a profound impact.

A prison had photos of all the prisoners in the pavilion. I saw a picture of a guy when he entered. He was overweight and robust, and seeing him in front of me, he didn’t look like the same person because of how much weight he had lost.

Francisco Proner/Farpa

Are these situations similar in all the prisons you visited throughout Latin America?

Yes, we decided to create this essay by blending photos from prisons in different locations because it was as if one was an extension of the other. There was no place we visited where we could say it was a model prison, where people have access to work, to produce something to pass the time, to education. That is very rare and very basic in all the places. It’s as if one prison ends and another begins. They are different countries, but all the prisons were one nation where humanity no longer holds as much value.

In the essay on the website, we don’t indicate which country each photo is from because it makes no difference. Everything is overcrowded. The food is rotten and horrible in all the places. There is no access to legal counsel anywhere, and medical advice is also tough to obtain.

Erick Dau/Farpa

Did you know why people were incarcerated there?

We avoided asking about the specific crime a person committed to avoid further marginalizing someone already in a complex situation. However, most crimes in Latin America are related to drugs, trafficking, or sometimes drug consumption, depending on the context. Even when individuals are part of a gang or a band, they are also involved in drug trafficking. Therefore, drugs, being criminalized, generate an informal market that becomes a source and subsidy for crime. It’s always present in their lives.