Looking at the world like a Kichwa child

Secreto Sarayaku is a transmedia project that explores the daily life and worldview of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku, originally from the Ecuadorian Amazon. We talked with Misha Vallejo, co-author of the work, about the collaborative aspect of this creative experiment with the community’s inhabitants.

By Alonso Almenara

For a work centered on the thought of a native people of the Amazon, Secreto Sarayaku is striking, first of all, for its experimentation with formats, technologies, and platforms: the project consists of a website, a photo book, a podcast, and an exhibition that was presented between November 2020 and March 2021 at the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Quito. It is an ambitious set made collaboratively by photographer Misha Vallejo and the original Kichwa people of Sarayaku: Vallejo’s images are combined with texts from the declaration of the “Kawsak Sacha” (Living Forest), where the Sarayaku present their cosmovision and formulate political demands, on behalf of themselves and nature.

These people are located in the province of Pastaza, in northeastern Ecuador, in the middle course of the Bobonaza river basin. It is an extensive territory with approximately 135,000 hectares, but 95% of it is occupied by primary forest, with a high level of biodiversity. Seven Kichwa community centers are located there.

This is not the first time Vallejo has embarked on collaborative work: this approach is present in projects such as Estados Foráneos (2012-2013), Manta Manaus (2015), Al Otro Lado (2015) y Siete Punto Ocho (2018)). But Secreto Sarayaku is where the Ecuadorian photographer has taken this principle further, blurring the edges of his authorship to achieve a work representative of a people famed for clearly expressing their interests and asserting their rights.

Sarayaku’s name went around the world in 2012, when the community and its leaders created a historical precedent in the region by confronting the Ecuadorian State, demanding a halt to the oil exploitation activities that the Argentine company Compañía General de Combustibles was maintaining in their territory, without authorization from the community. The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights declared that the community’s property rights, cultural identity, and survival had been violated and ordered the cessation of oil activities and measures to repair the environmental impact.

The origin of Secreto Sarayaku dates back to 2015 when Vallejo learned of a call for artistic projects from the Humboldt Association / Goethe Center of Quito, which sought to promote the creation of works that reinterpret the Kichwa philosophy of Sumak Kawsay (Good Living). He is 38 years old and was born in Riobamba. “I started in photography late, doing photojournalism,” he says. “Then I opted for documentary photography: the work I’m most passionate about involves the environment and identity. I’m also interested in working on what has become known as ‘glocal narratives,’ those super-local stories that simultaneously exemplify worldwide events. Secreto Sarayaku would fall into that category.”

After five-year research, going back and forth from Sarayaku, the Ecuadorian photographer presented a work that tries to capture the daily life in this community, its ancestral philosophy, and the coexistence of its traditions with the influence of the Western, modern, and urban world. The exoticizing idea of an Amazonian village isolated from the outside world is broken in photographs that explore, for example, the relationship of the inhabitants of Sarayaku with communication technologies or their vocation for digital activism.

Ecuadorian-Salvadoran curator and art critic Ana Rosa Valdez has described this work as “one of the most solid projects of contemporary photography in Ecuador.” In the words of the expert, it is “a tribute to the beings who resist in the Amazon, who affirm their existence against the extractivist sign imposed by state and business forces and by an urban society that, complicity or cynically, imposes with its ways of life a sacrificial logic to the ecosystems and jungle territories. It is a tribute that celebrates the self-determination of the Amazonian peoples”.

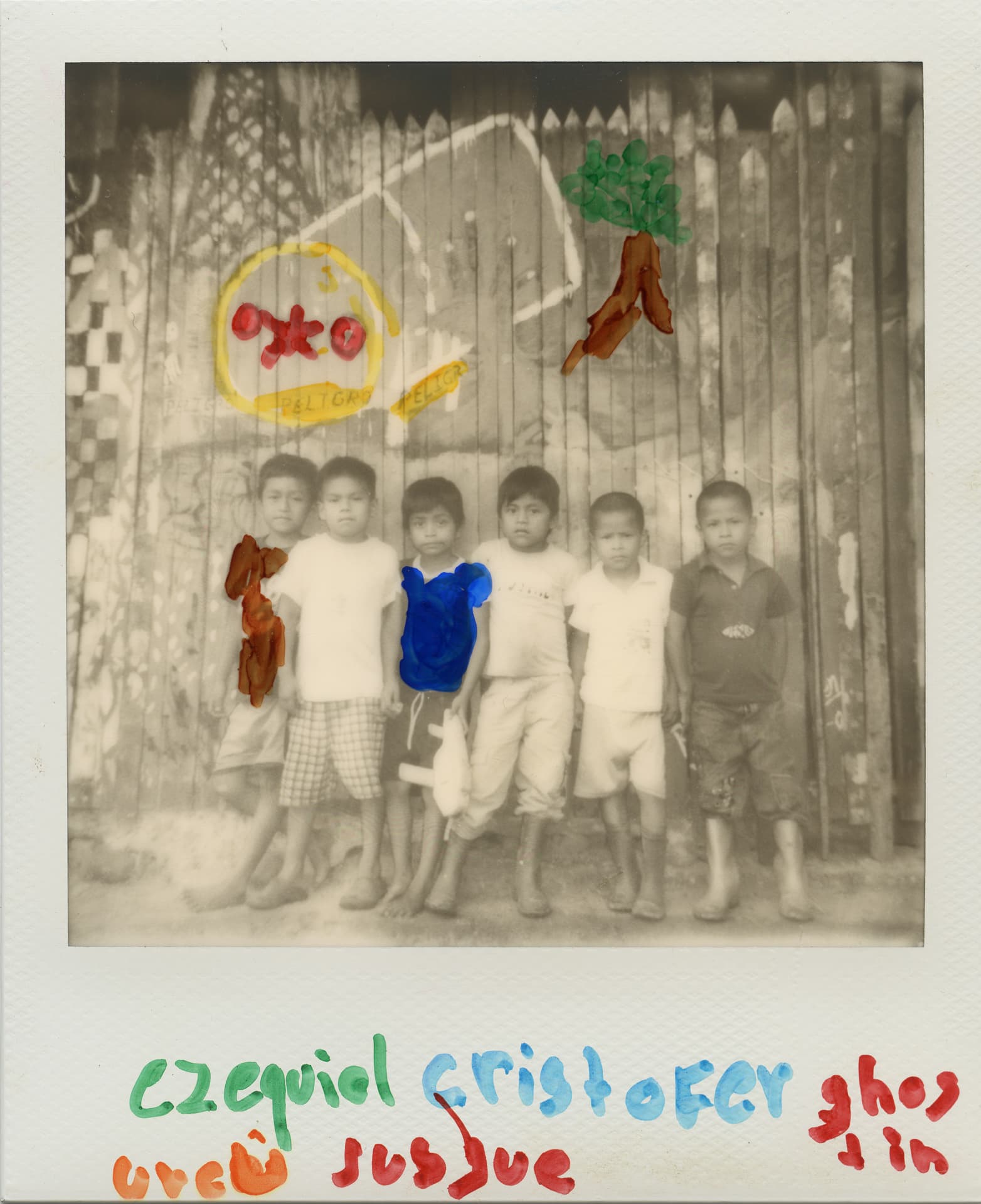

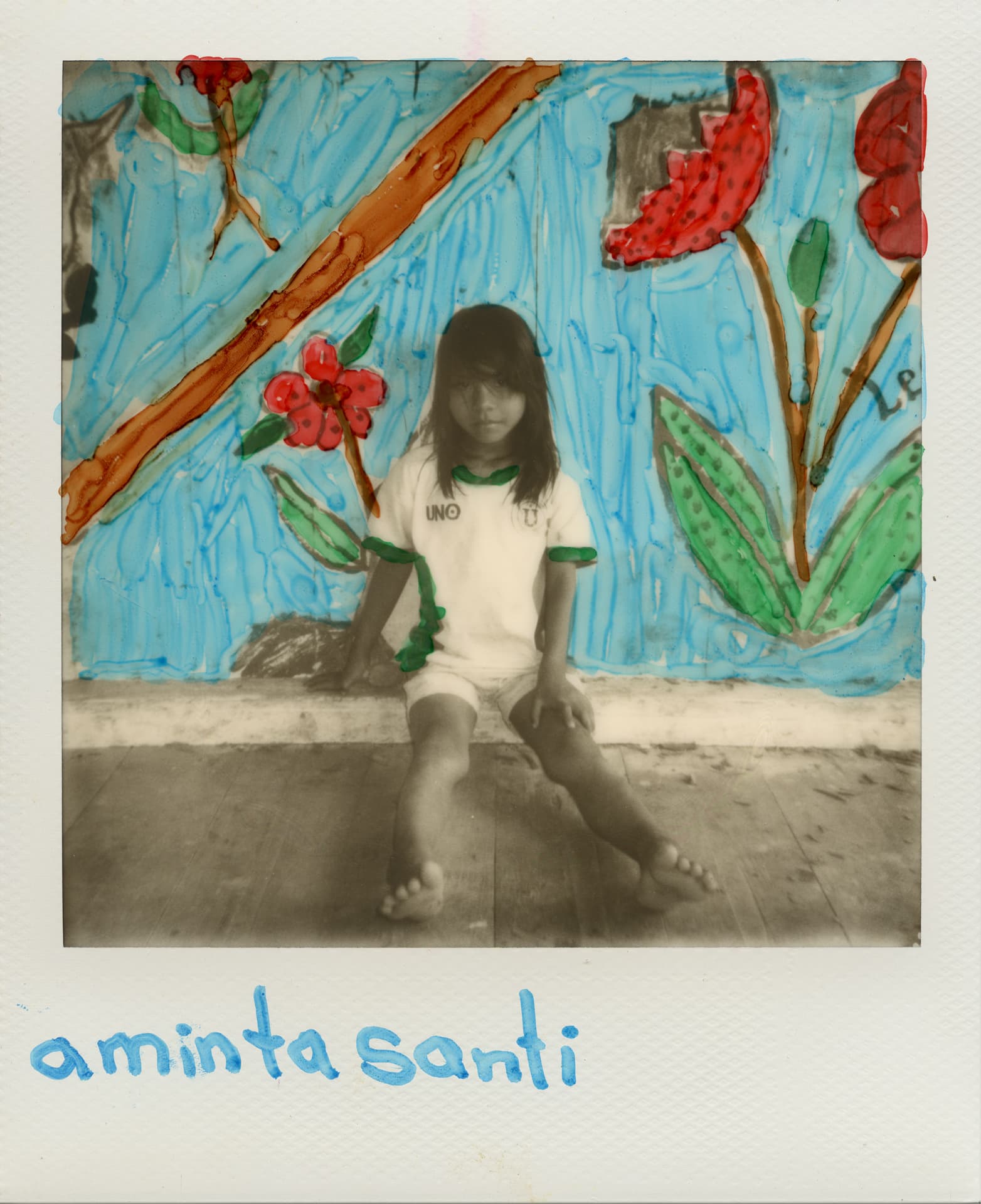

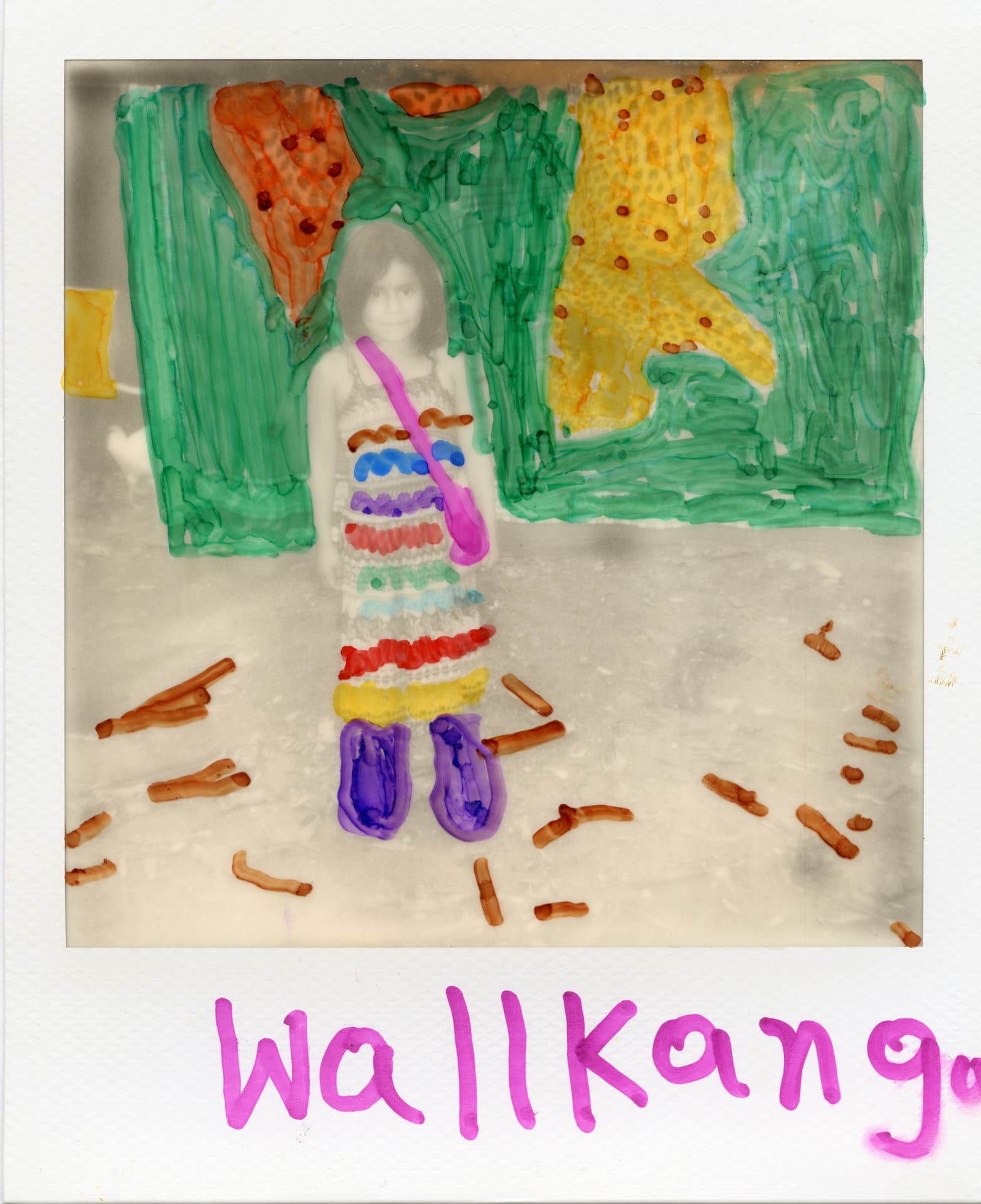

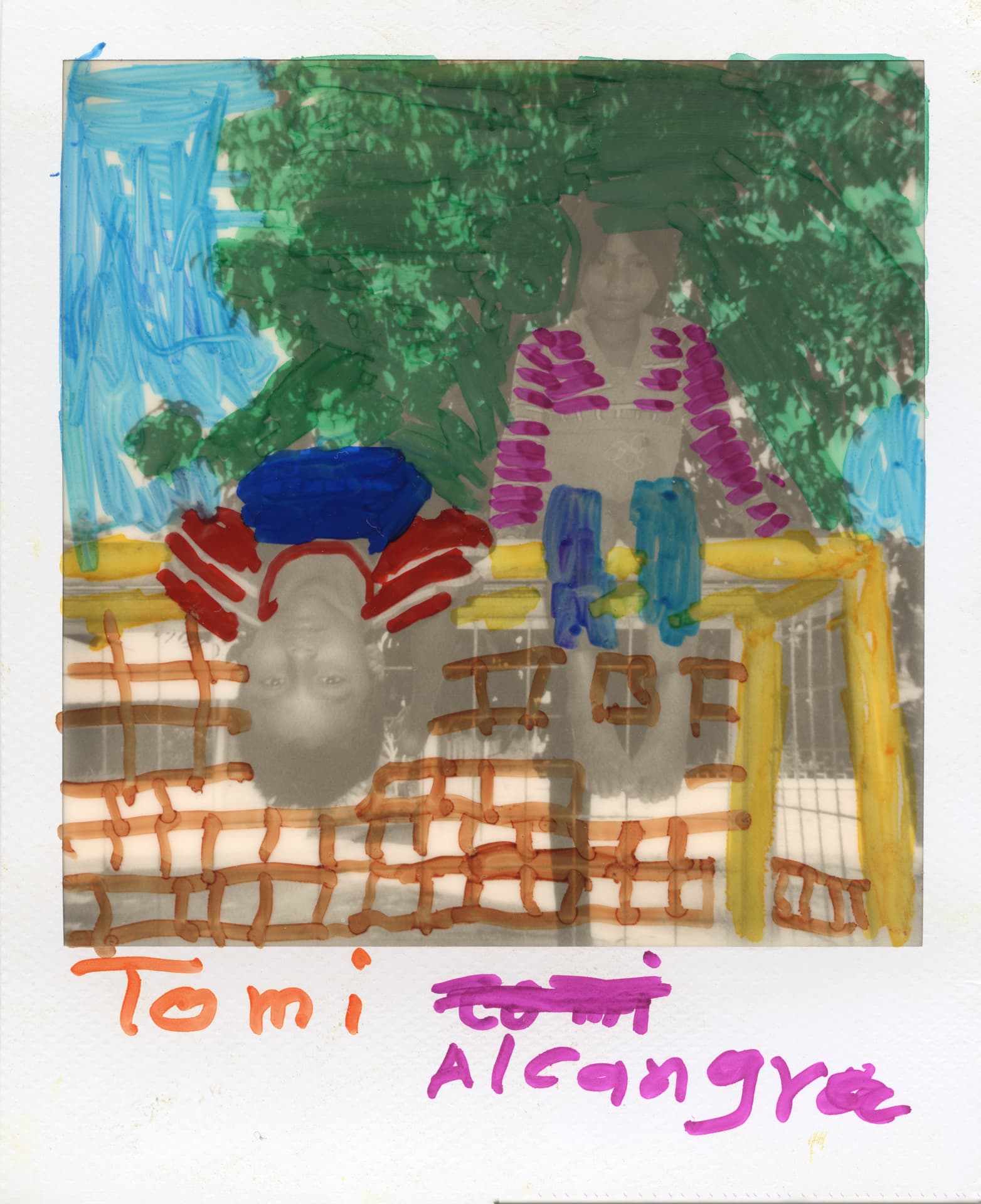

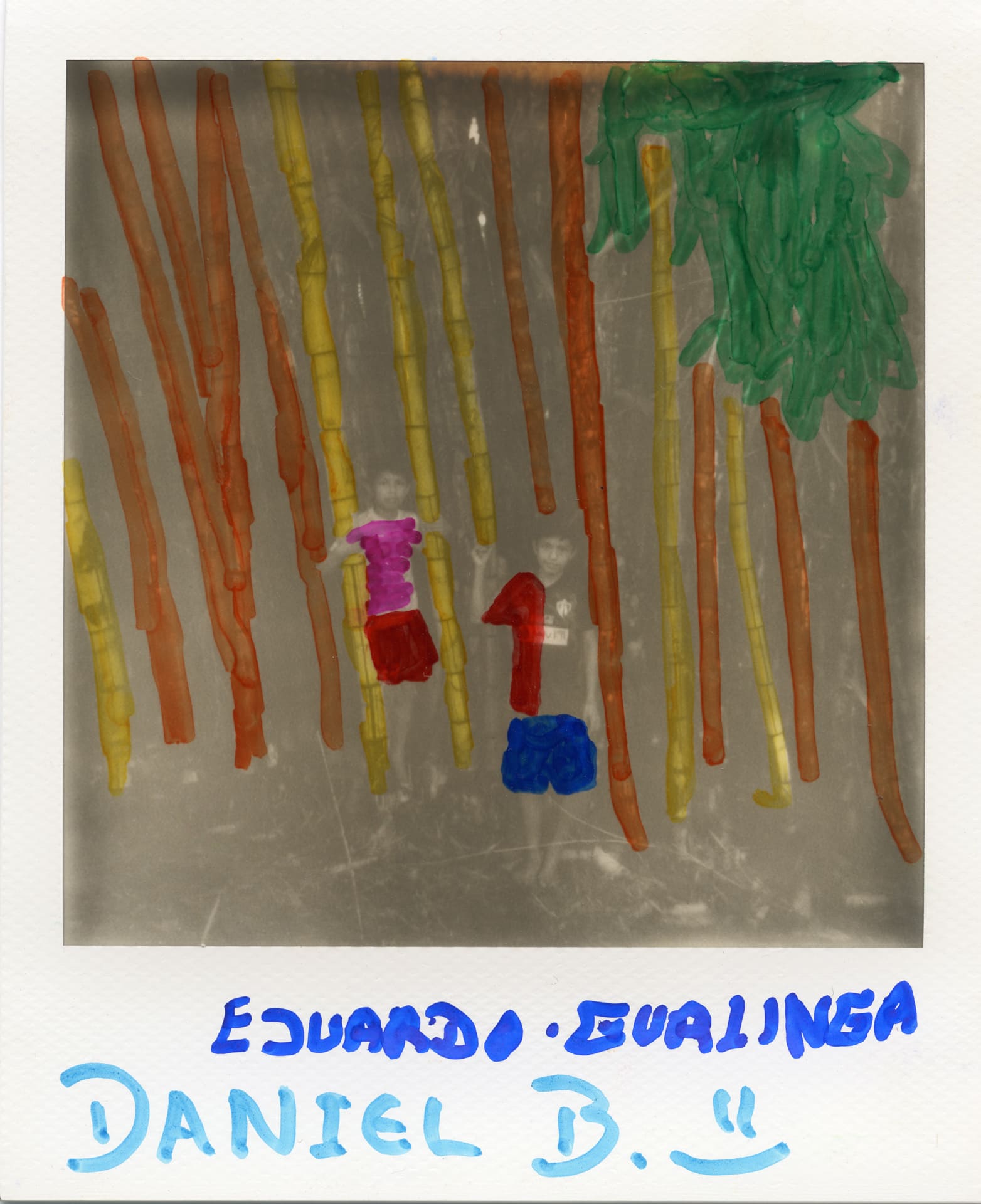

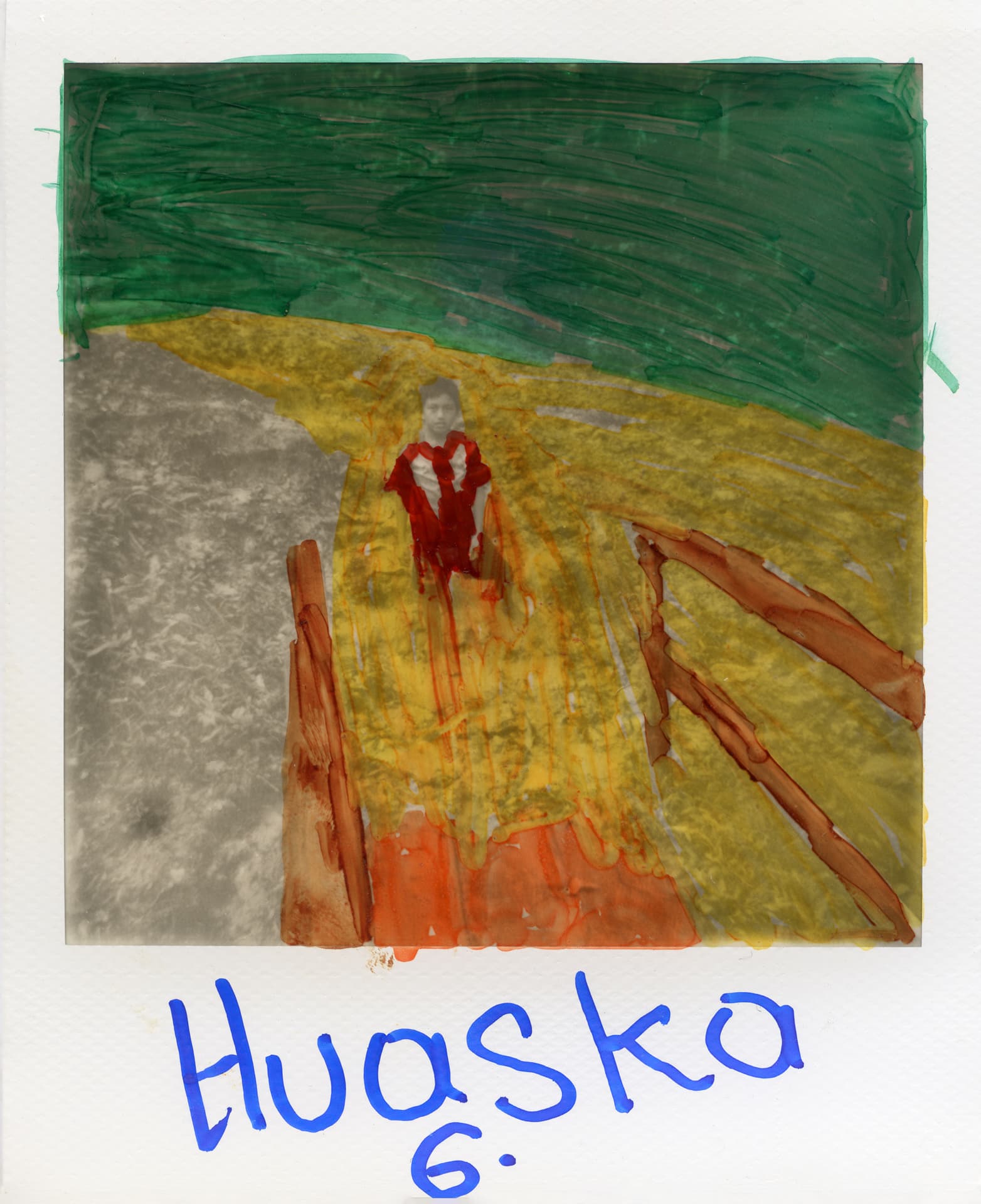

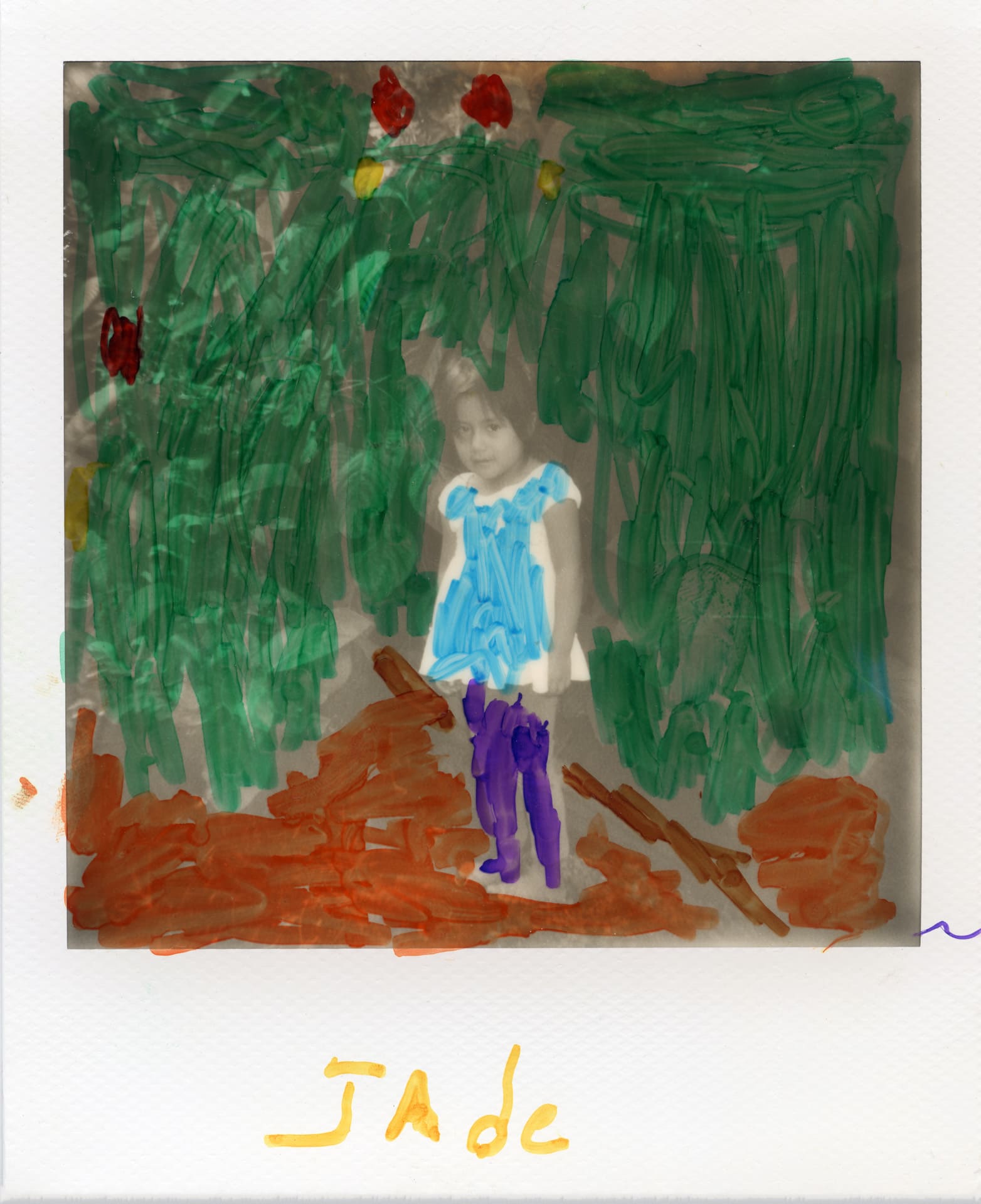

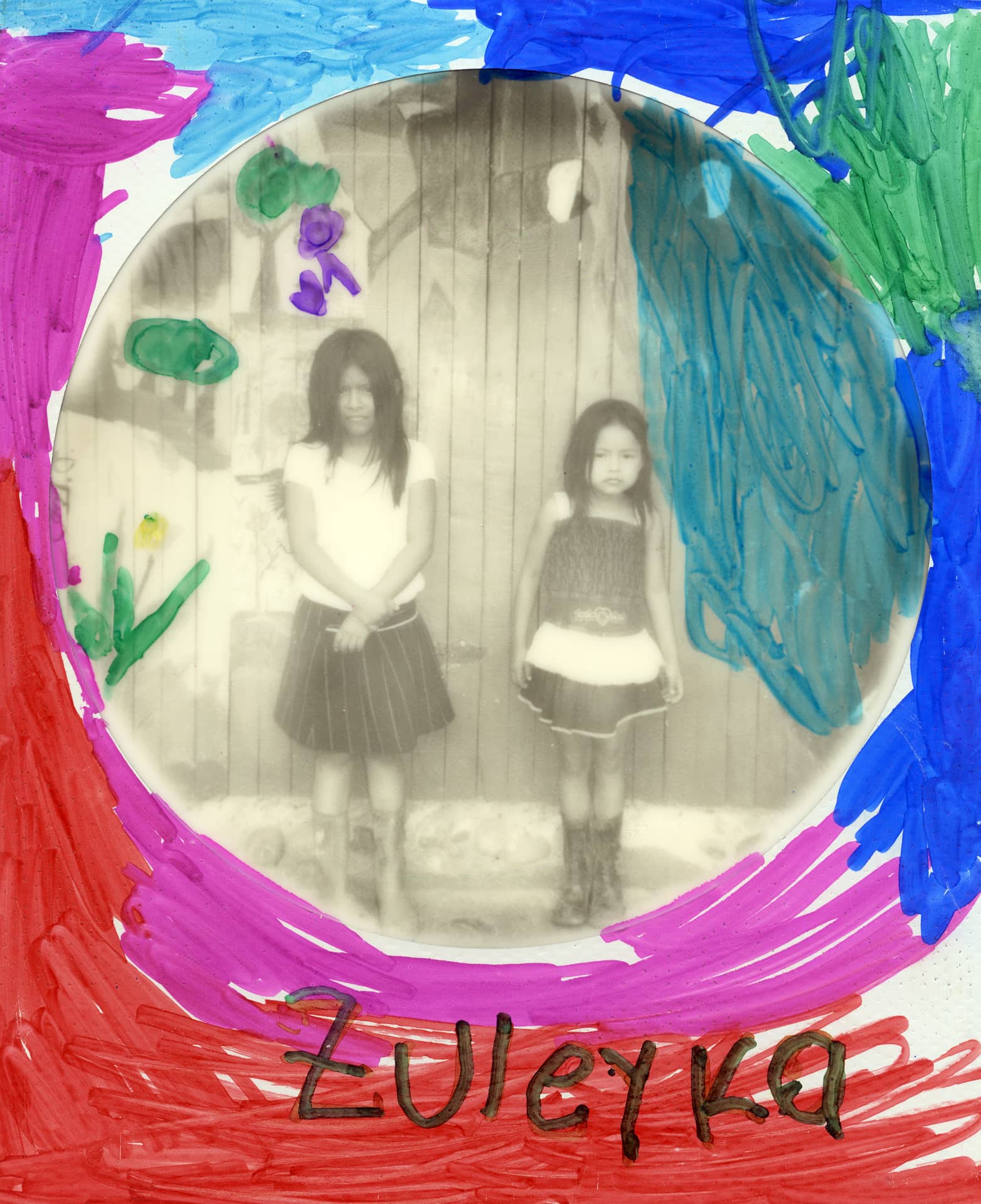

In this interview, we talked with Vallejo about the collaborative aspect of his work, accompanying the text with a series of his portraits of children from the Sarayaku community who intervened by themselves. In the 2020-21 exhibition at the CAC in Quito, these images hung suspended on a wooden panel, falling like rain. To see them,” observes an Artishock reviewer, “it was necessary to bow slightly like someone bowing.

“[The Kichwa] asked me: what will you leave to the community in exchange? In all my career, and I say this with shame, I had never thought about that. They were obvious to me: Western man has visited indigenous communities for centuries to obtain knowledge or profits. They go to extract compounds from the plants they patent and sell without leaving anything to the communities. And we anthropologists and documentalists have repeated that scheme: we extract knowledge with which we obtain prestige.”

How did you get involved with the Sarayaku people?

I was curious about this community that, in 2010, gained a lot of recognition after suing the government of Ecuador and winning the legal battle two years later. It was the first time that an indigenous community had won a lawsuit of that magnitude against a national government. I was very interested in getting to know them, so when the call from the Humboldt Association came up, I proposed a project based on the Kichwa philosophy of good living. It is an ancestral philosophy born in Kichwa communities but was later appropriated by Rafael Correa’s government, almost turning it into a campaign slogan. So that in Ecuadorian society, it became frowned upon to talk about it, which seemed absurd to me.

In 2015 I was finally able to travel to Sarayaku. It was not easy to enter because it is a community that functions like a state: it has a president, vice president, a governing body of Curacas (indigenous chief), and even a communication department and a biology department, which are like ministries. It is pretty bureaucratic, and you need a permit to enter. But the admission process was exciting because besides the obvious “who are you?” and “what are you going to do?” questions, I was asked something that left me thinking long and hard: “What are you going to leave to the community in return?”

In my professional career, and I say this with shame, I had never thought about it. They were very clear: they told me that Western man has been visiting indigenous communities for centuries to obtain knowledge or profits. For example, they go to the jungle to extract compounds from the plants they patent and sell without leaving anything to the communities. The same happens with oil, minerals, and timber. And we anthropologists and documentalists have repeated this scheme: we extract knowledge with which we obtain prestige.

After thinking about it for a while, I told them that I am a photographer and could lend them my photographic work in exchange for whatever they needed during my stay. And that’s what I did: the first day, they asked me to take pictures of a catalog of medicinal plants they were preparing. That day I learned a lot about botany. And from then on, I traveled to Sarayaku until 2021, which was the last time I went, and I remember that we did some photo workshops for children.

These trips have given me the possibility to strengthen ties with the community, especially with José Miguel Santi, who was the one who received me and who is now the head of communications of Sarayaku. We have forged a friendship, and I must say that he played an essential role in the project, as he did many of the interviews that appeared on the website. He did them in Kichwa, something I could not have done.

Where did the idea of making a website come from?

When we did the photography workshop with the kids from the community, I realized that they were all using their cell phone cameras. They handle technology quite well to communicate what is happening in the territory. That motivated me to make a web page in this activist logic of looking for a simple way to reach as many people as possible. We all know that photobooks and exhibitions are for a small audience: we wanted something easy to access and free. But we didn’t stop at the project’s website: one of our ideas with José Miguel was to create an Instagram account for Sarayaku. That account has remained a communication channel managed by the community: they report on their festivals and crafts and even discuss issues such as mining and oil exploitation. They already have a website and an official Twitter account managed by the communications department. They even have a meme page on Facebook that is amazing.

E·CO/23]

This work is one of the inspirations for E-CO/23], the new edition of our meeting of photographic collectives, which this year will have as its thematic axes: Ecologies, Territories, and Communities.

Through this call, we are interested in gathering stories of sustainable development, community movements, and ways of inhabiting the land in the community to achieve new narratives built from the plurality of collective creation.

Each selected project will receive support of 5,000 euros for its production. The tasks can be presented by existing collectives or by groups of people working in collaboration for this project in an interdisciplinary way.

The selected groups will participate in a collective process of production and reflection that will be accompanied by pedagogical support with specialists in the themes.

Once the production stage is completed, the project results will be presented in one or more exhibitions that may rotate and on the digital platforms of Fundación VIST, the AECID, and the participating Spanish Cultural Centers or the institutions they designate. The aim is to consolidate networks for creating and circulating visual narratives in Ibero-America.