Looking for glimpses between the past and present

Photographic archives are part of Celeste Rojas Múgica’s raw material. For her, every time an image from the archive is revisited, it changes. It transforms. Under that premise, the Chilean artist developed Una Sombra Oscilante, taking records from her father, and Ejercicios de Aridez, where she combines images appropriated from various archives with others of her own. Celeste understands the image in both projects as a luminous meeting point between the past and present.

By Marcela Vallejo

Visual artist Celeste Rojas Mugica is surprised that her images are primarily in black and white. She says she works a lot in color, but eventually, the projects end up in monochrome. “It’s almost inevitable,” she says. Photography has accompanied Celeste’s life since she was a child; her father was a photographer and taught her to make images and develop them from an early age. That’s why she says she has always been a photographer, and now life is leading her to filmmaking.

For Celeste, it is fundamental to understand that her work is constructed from a precise place of enunciation. She is interested in talking about the territory and the history that runs through it, thinking about it, and asking questions about it. Her work is about Chile. It could be said that this artist’s work is closely related to memory, but it is not about reconstruction exercises. It is about reflecting on the exercise of remembering, revisiting, and forgetting and how this reverberates in the present.

The artist works with archives, perhaps the most important of which is that of her father. He was a militant of the Revolutionary Left Movement during the dictatorship and contributed to the movement with photography. That meant living in hiding and constantly moving, but he had to go into exile at some point. With her father, Celeste has not only had a privileged window to understand a part of her country’s history, but she has also had access to many images, narratives, and visual techniques.

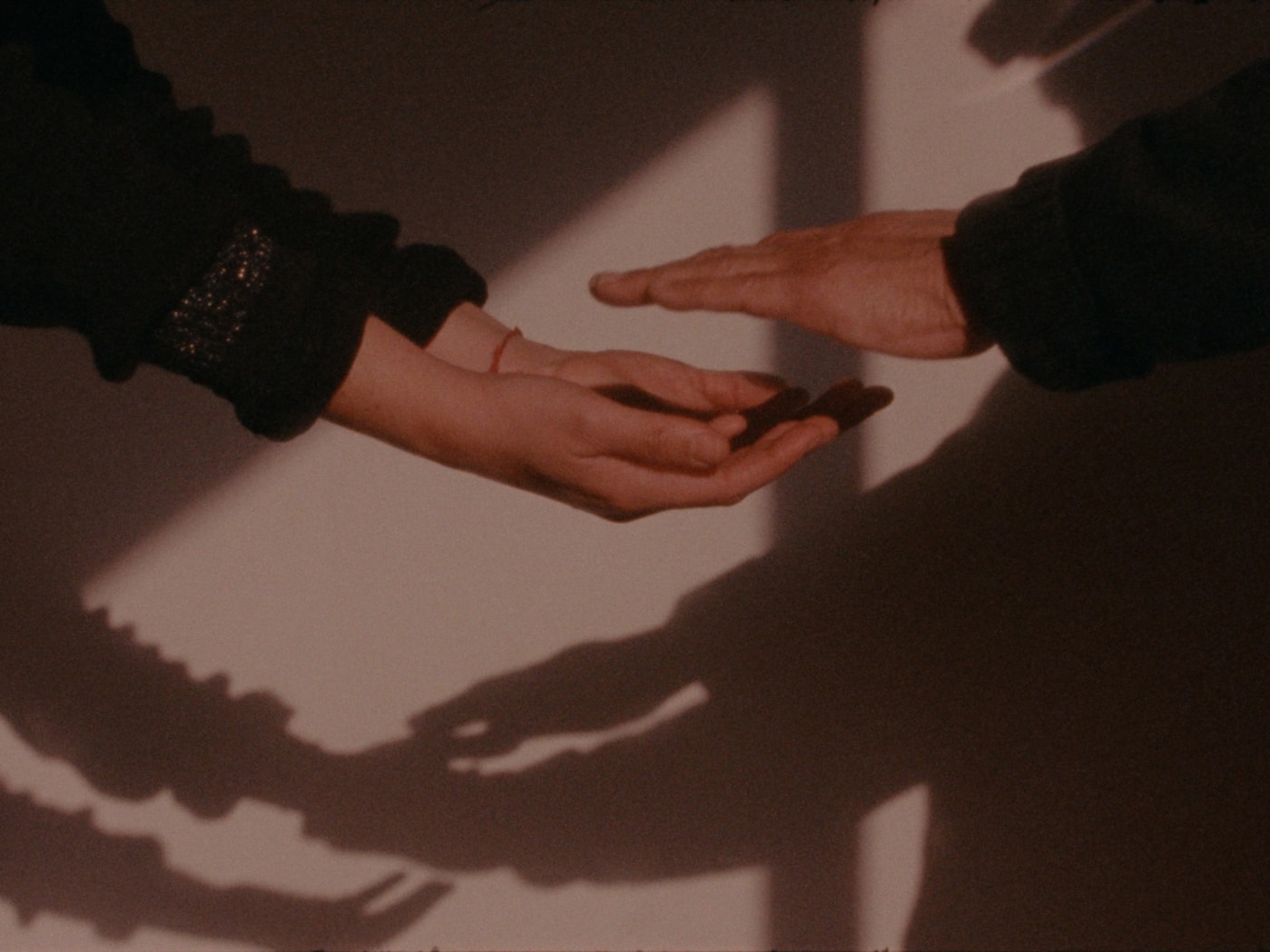

Her dad has been an excuse to see the past and understand and ask questions. With him and his archive, Celeste developed the project Una Sombra Oscilante, which is based on “a series of questions about the unrepresentable, but through the idea that in the photos there is an imaginary vanishing point, something is possible to materialize.”

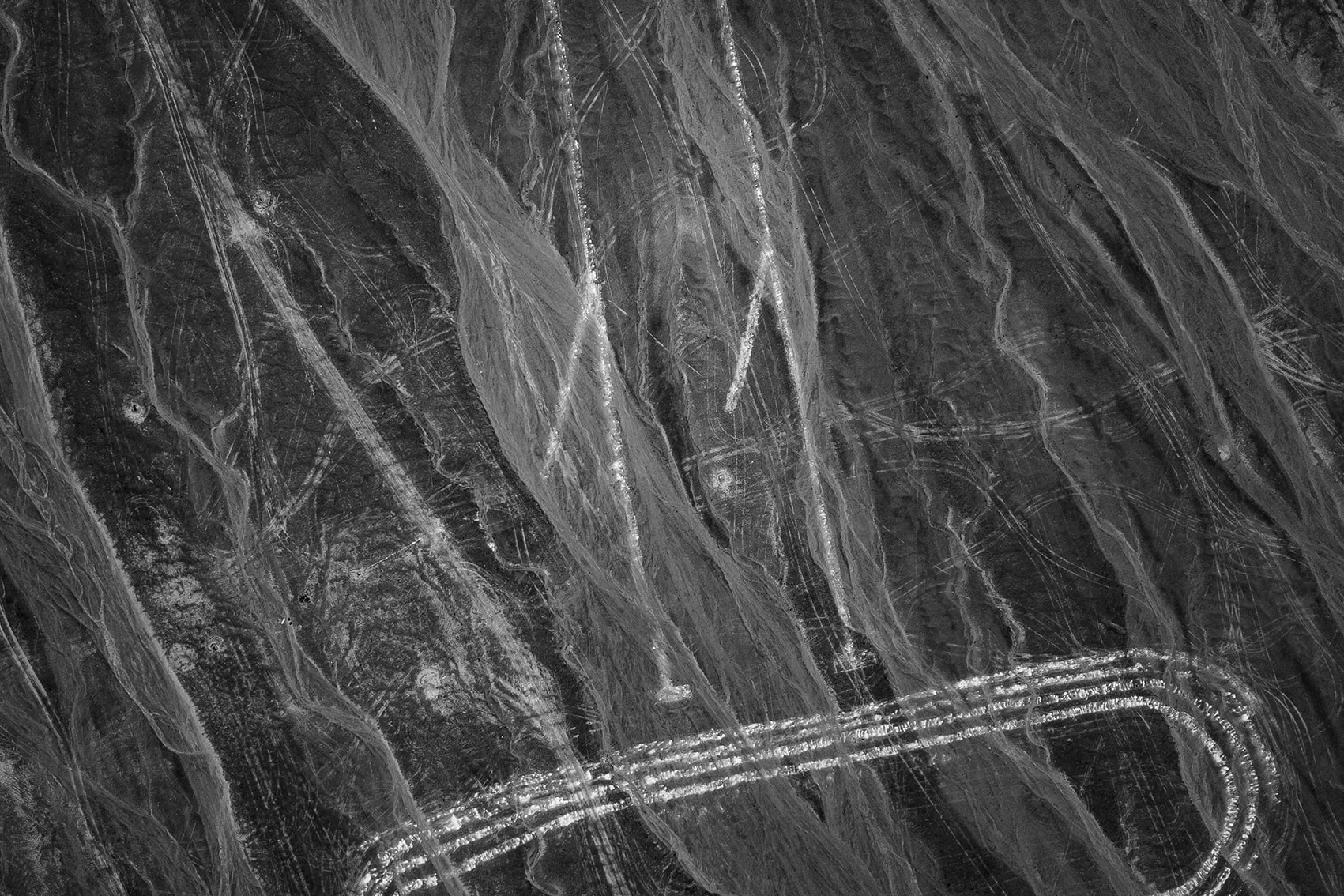

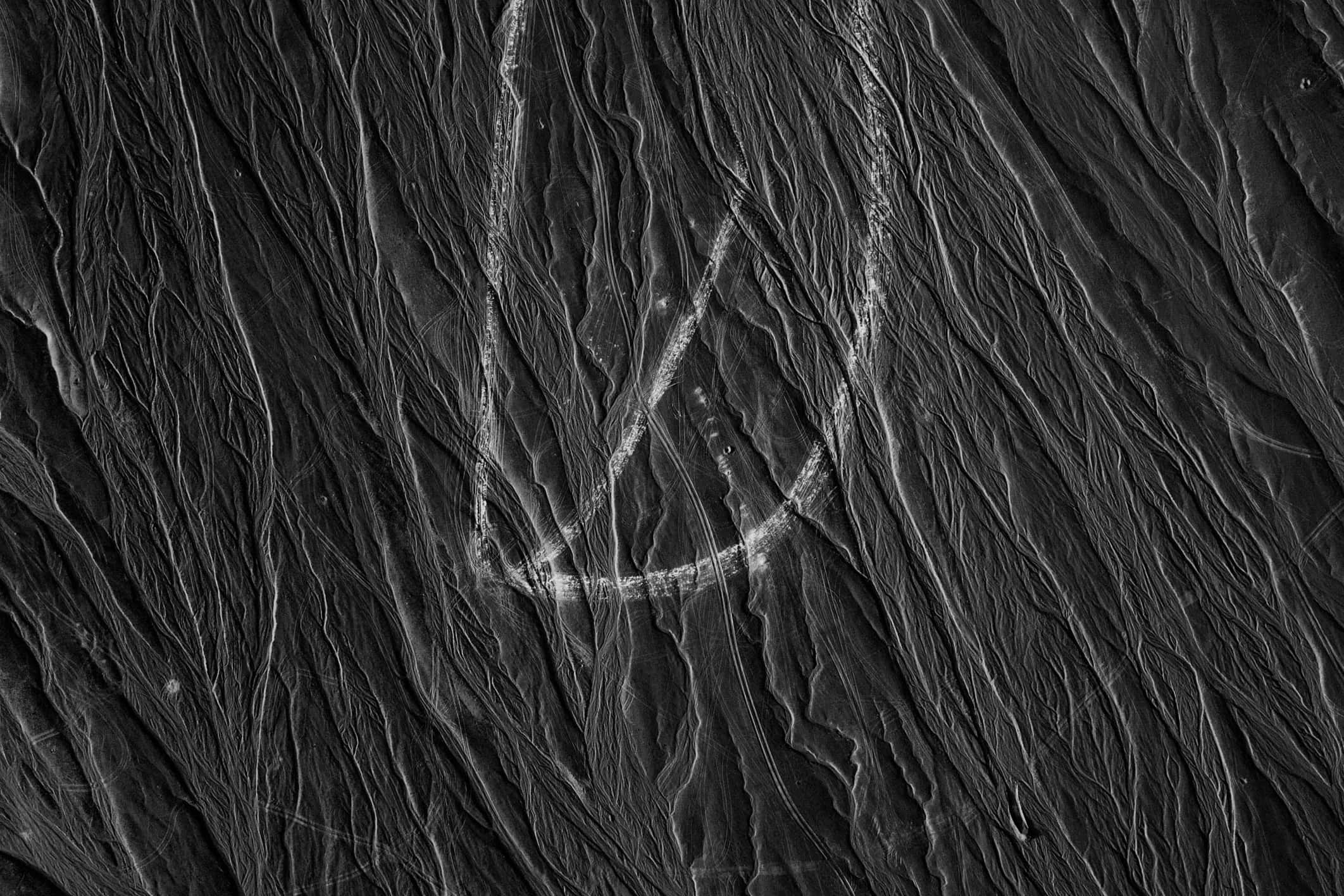

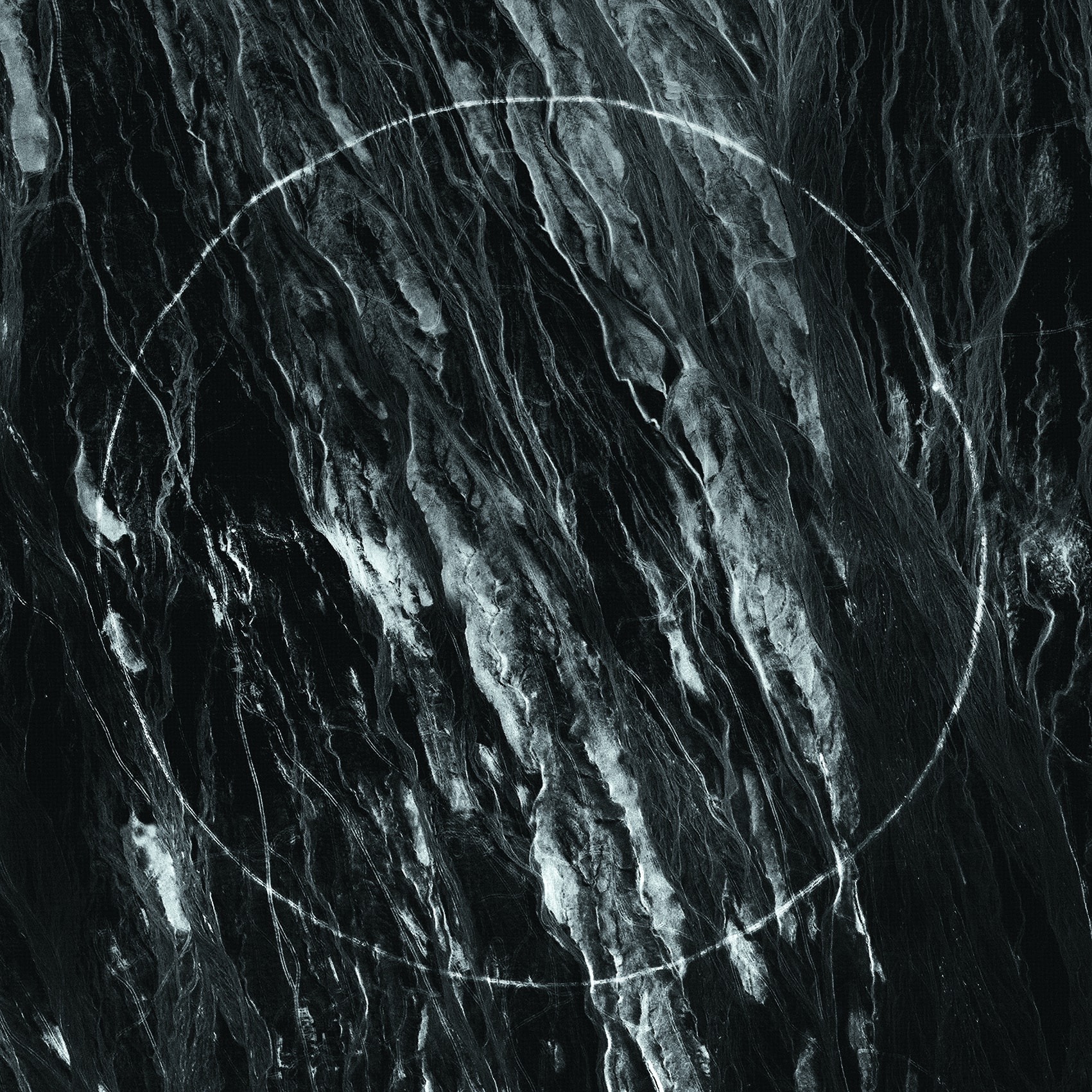

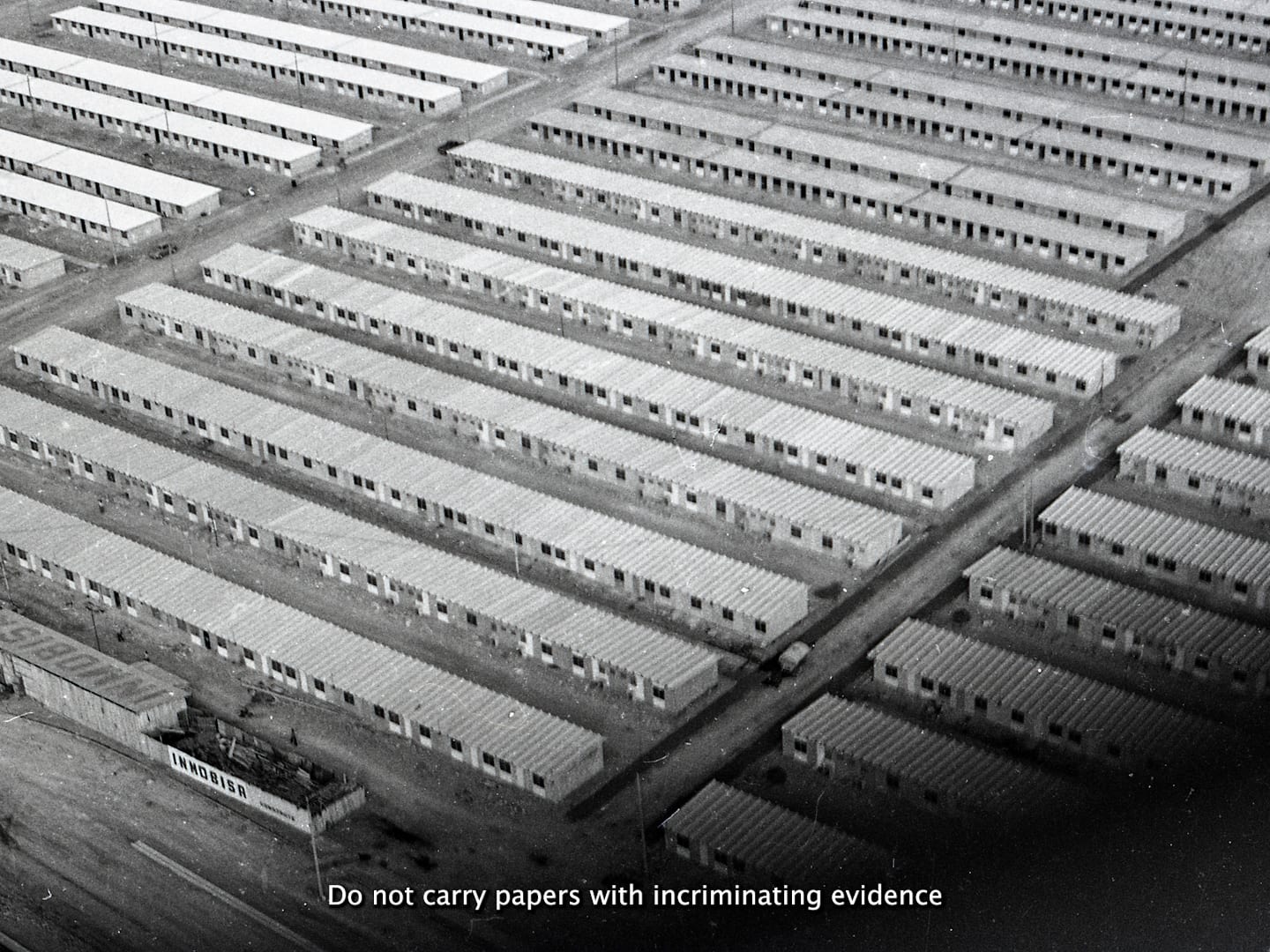

The work of appropriation of archives also led her to make Ejercicios de Aridez. This work has as its starting point the following: “In 2011, a woman, a member of a group of relatives of the executed in Calama, Chile, received an anonymous envelope with the image of a huge bald knife traced over the Atacama Desert. On each side of the hilt were traced and petrified the numbers 73 and 78, and a perfect circle of approximately 600 meters in diameter”.

The Corvo (a curved sable) is the Chilean armed forces emblem. Why did this woman receive this image? Who dares to make such an intervention on the territory? Ejercicios de Aridez has several facets: an installation, a website, and it has become an object of mediation to speak through memory, the past, the present, and the future.

For Celeste, memory exercises go beyond the reconstruction of the past. Thinking about what happened, revisiting archives, and reliving memories can materialize ideas of utopian worlds and other ways of being and being in the world.

“I’m interested in thinking [memory] not as something static or as nostalgic, but rather to draw on the mechanisms of memories to think about the present and to think about how archives, reading them in the present, are also reconfigured, transformed, are elements that are in constant movement.”

When discussing your work, some tend to frame it in the construction of memory. Do you agree with that way of understanding it?

My work generally has a particular interest in memory or what I understand as memories, not as a single concept. I’m interested in thinking about this issue, not as something static or as nostalgic but rather as resorting to the mechanisms of memories to think about the present and to think about how archives, reading them in the present, are also reconfigured and transformed; they are elements that are in constant movement.

In that sense, for you, is memory constructed or reconstructed?

Human beings can’t remember everything. It is inevitable. I think it is a combination because there are things we cannot control, we cannot determine what we are going to remember and what we are not going to remember, but we know that we cannot remember everything. Moreover, memory has a very random way of configuring itself in our brain and is determined by subjectivity in contact with the world.

Memories are also collective and part of social processes in which we place specific memories over others based on what we think or desire. This somehow unstable capacity of memory, for me, is something interesting and not a problem in negative terms.

Your work has a strong basis in photographic archives. How do you understand archives, and what do you look for in them?

I’m interested in looking at the archive from a critical and situated perspective. I think that the place from which I enunciate myself is relevant. It’s not the same to work with archives; I somehow feel it’s not my place to work because I have a place in this world, which is loaded with a series of issues.

I work with archives that are mainly photographic documents. When I speak of a critical perspective, I mean that these archives with which I work have this capacity. On the one hand, to allude specifically to something that has happened and is a document of the real and of history, but at the same time, it can become something else, and every time we look at it again, it can be something else.

So I am interested in thinking about these materials in this double dimension: in their capacity to refer to an era, to a document, to a fact, to specific conditions of production, to particular events, but at the same time, in their capacity for transformation or the performative power they have to offer us always another possibility as long as we look at them again and put them about the now. To a certain extent, the archive is like a body in movement. The challenge, or what is interesting, is to think critically about the relations between both possibilities.

I understand that a large part of your work is based on the archive of your father, a leftist militant during the dictatorship in Chile. How do you approach it, and which other archives do you work on within the project of Una Sombra Oscilante?

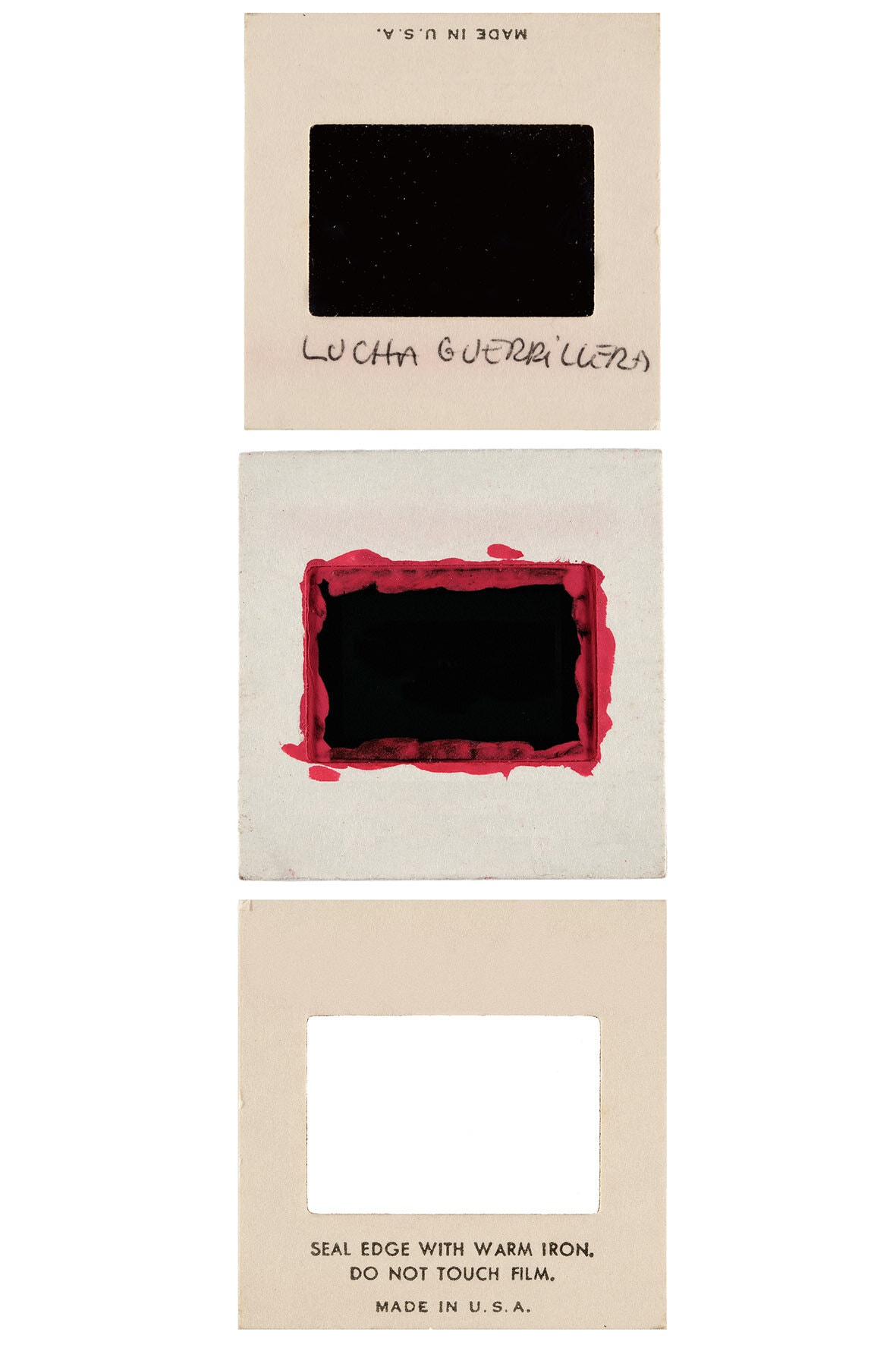

In the case of Una Sombra Oscilante, it is a project with several parts. I am now in the post-production of a feature film -my master’s project-. In this case, I work with a series of photographs that comprise the archive of photos my father took during his years of militancy during the Chilean dictatorship and exile. The exciting thing about this archive is that it refers not only to the existing images but also those that don’t. There are many of the photos that my father took during his years of militancy during the Chilean dictatorship and exile. There are many photos my father took that no longer exist, and I am interested in thinking about how to summon them and how to demand that invisibility.

For example, many of those photographs had to disappear at a particular moment for security reasons. Or also, as my father was a photographer for the Revolutionary Left Movement, they were photographs that were not intended to be preserved at the time. But many photos do not exist because the same transit of the exile and the return of himself fleeing from his history have made them not be there.

And in the case of the project Ejercicios de Aridez?

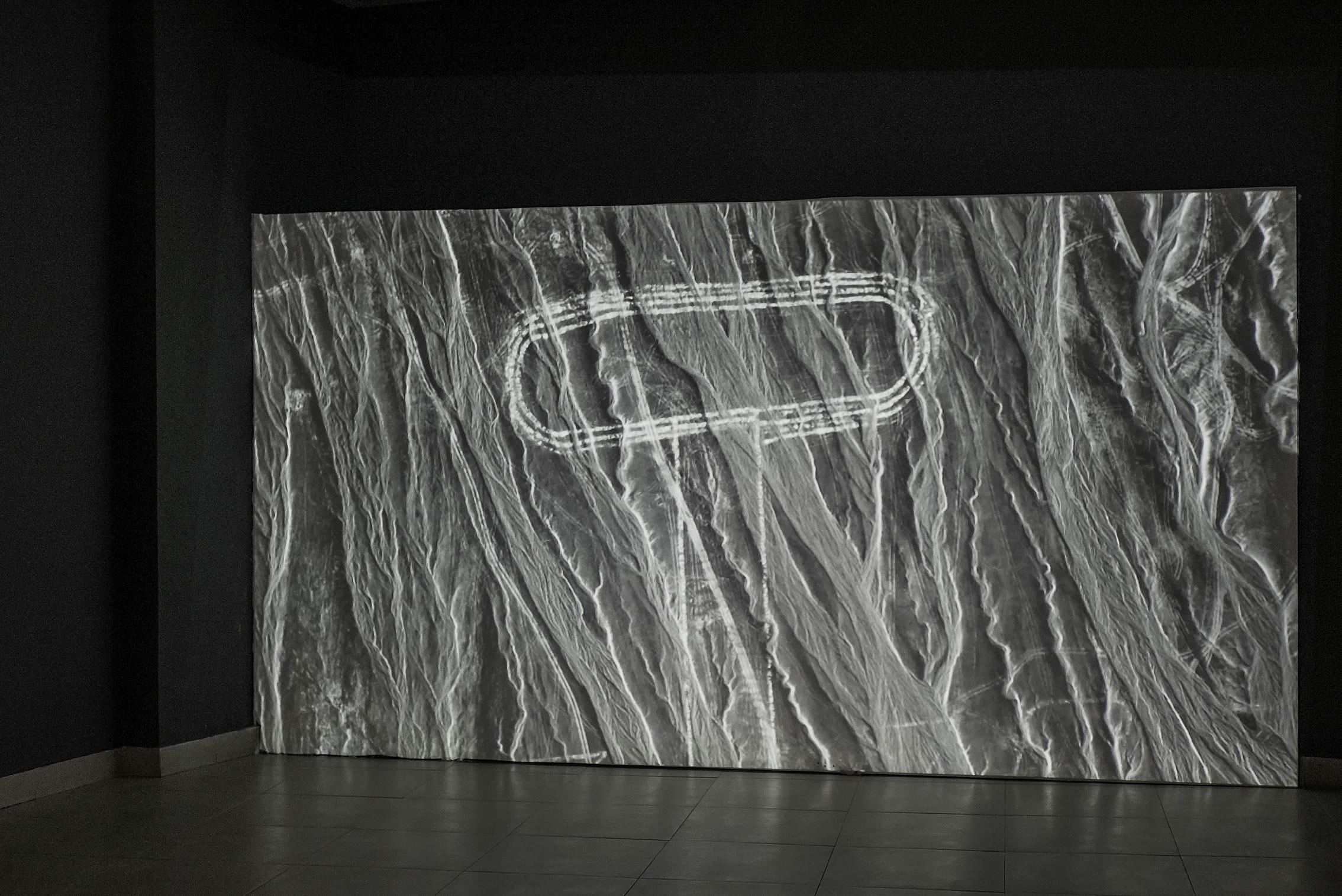

Ejercicios de Aridez works on a relationship between documents of different origins. That is to say. There are Google Earth files with satellite captures of a specific territory, archive photographs of exhumations of bodies of disappeared people, and images I produced in the present. When you see it exhibited, the work does not refer to which images are mine and which are not, but there is a kind of communion and interrelation of these elements.

An oscillating shadow is a project that has involved constant dialogue with your father. How have you worked on this dialogue beyond the image?

The book of Una Sombra Oscilante, edited by Asunción, contains images from the archive. Now and then, there are small fragments of e-mail correspondence we had over the years, in which I was working with the archive, but my e-mails do not appear, only his, and it is understood that he is responding to someone. The film, which is in post-production now, is a work where my father is on stage and is the only character. I am behind the camera, I never appear, but there is a game between us. There is my voice and his constant. It’s like a game around photography, a dialogue between the history of a country and the ways of making images.

What does your dad think of all this work?

My brother is a writer and writes a lot about my dad. So he is a bit used to it, but he is a very low-profile person. He has always been very embarrassed about the fact that his children are so interested in him. Actually, it is also an excuse; the figure of my father allows us to think about a historical moment in a series of conditions and situations that crossed and crossed a country.

But precisely because of the conditions in Chile, my father was frightened by the fact that we were working on his own history for a long time. In Chile, the armed struggle movements at the time or of the revolutionary left until today are not experiences that are vindicated from the present. Such people like my father have had to live historically with the idea of hiding, somehow maintaining clandestinity.

Ejercicios de Aridez is a project that generates a lot of intrigues. It all starts with the photograph that the activist receives: an aerial image of a vast Corvo drawn on the desert floor. Why do you think she received that photo?

There is nothing obvious because there is also a lot of ambiguity in all this data or information due to this country’s conditions that have not judged those responsible. In Chile, there are more than 4000 disappeared bodies since the last dictatorship; there are pacts of silence, so there are many things that we do not know with certainty why they happened, but this was probably intimidation in the context of a trial that was taking place. This woman is a relative of a person who was executed politically, and the knife is an emblem of the Armed Forces.

Probably, they drew this image not to intimidate but to feel the right to mark the territory in this way with such premeditation, violence, and brutality. And yes, the facts surrounding this project are very intriguing. The project does not seek to give an answer but rather to place us in that state of intrigue and confusion about how to surround an enigma and the most brutal violence that can exist.

Surrounding it in what sense? Because I believe that it is something that precisely cannot be understood.

The project aims to make it evident that there are things that we will not be able to understand because they are so brutal that they escape our understanding. And at some point, it is good that this is so because if we were to fully understand those minds capable of thinking something like that, we would become those minds.

The distance we have is because of our space with exercising horror, so there is something ungraspable in a mess, indescribable, indecipherable. The project seeks to place itself in that uncomfortable place and also to persevere in searching for answers knowing that we will not find them anyway.

In La Dimensión Desconocida, by Nona Fernández, something that caught my attention is a reflection she makes in which she wonders if, at some point, we will be able to wake up from the dream of horror and if when we wake up, we will be able to recognize what we have done. That first person strikes me. It makes me think a lot about whether we can involve ourselves in these forms of violence in this way. She is from a different generation than yours, but I would like to know if you feel involved in this way.

We are all involved because we are social subjects. But I know that I am not responsible for these crimes. I don’t know exactly what she is aiming at, but I believe that repairing, transforming, and enabling other possible conditions in the present corresponds to all of us. When I told you about situated thinking, I also meant that this corresponds to all of us from our places.

So, that sense is responsible, but I am also clear that there are structural conditions that make that there are those who have more power than others and have committed the crimes they have committed precisely because of those mechanics of power and for being in places where I am not, nor would be, nor am I interested in being. So my practice is in another place and seeks to raise other discourses.

I don’t know if I read this before or after delivering the Truth Commission Report here in Colombia. In the delivery, Father De Roux, the director of the Commission, asked why we allowed this to happen. And I have thought a lot about this question, could we have stopped it?

That question enables reflection. If that question does not appear, everything else around it probably does not appear either.

When I talk about the mechanics of power and all these structural conditions that made it possible, for example, a dictatorship like the one in Chile, I am aware that this meant a blow to the experience of many people, which annihilated in literal and not so literal terms those people involved.

Considering all the forces mobilized to do a project as complex as a dictatorship work for 17 years, you have to think about things. It was a project of great complexity and sophistication. But the correlation of forces was abysmal, so holding the communities responsible for something that completely exceeded their possibilities is absurd.

Now yes, I believe that the commitment to our history and our processes is fundamental, which is why I am someone who vindicates what my father and mother did. I am interested in continuing to summon it, studying it, and thinking about it, even in terms of what was done wrong, because we should not romanticize those experiences either.