Looking yourself through others

A decade ago, Argentine-Mexican Mariela Sancari abandoned photojournalism to start her path: thinking of her works and photobooks as autobiographical devices but loaded with imagination. Moisés and El Caballo de Dos Cabezas are examples of this search. Mirror games where she reflects, at the same time, a part of her history and that of others.

By Marcela Vallejo

After five years working for the newspaper Reforma, Mariela Sancari decided to resign and start a more personal path. It happened in 2011 when she entered the Contemporary Photography Seminar at the Centro de la Imagen in Mexico City. That, Sancari says, was the beginning of her autobiographical exploration: since then, she began to think of her works and photobooks as family albums. Not like the traditional ones, with pictures of relatives or some birthday. They are, instead, searches for memory, imagination, and, above all, stories that could be.

For Sancari, self-referentiality is a way of thinking, a path to self-knowledge. Although, her photos don’t need to be self-portraits. The important thing is that they allow her to imagine and think. Thus, one that interests her is to break the relationship with the referent: photography sometimes remains trapped in the idea that it faithfully represents what appears in the image. By breaking that relationship, possibilities open up for the gaze, where the creation of meaning begins.Achieving this also implies “thinking not only about what the images contain, but also how they are presented.” Sancari has explored this last factor through the editing of photobooks.

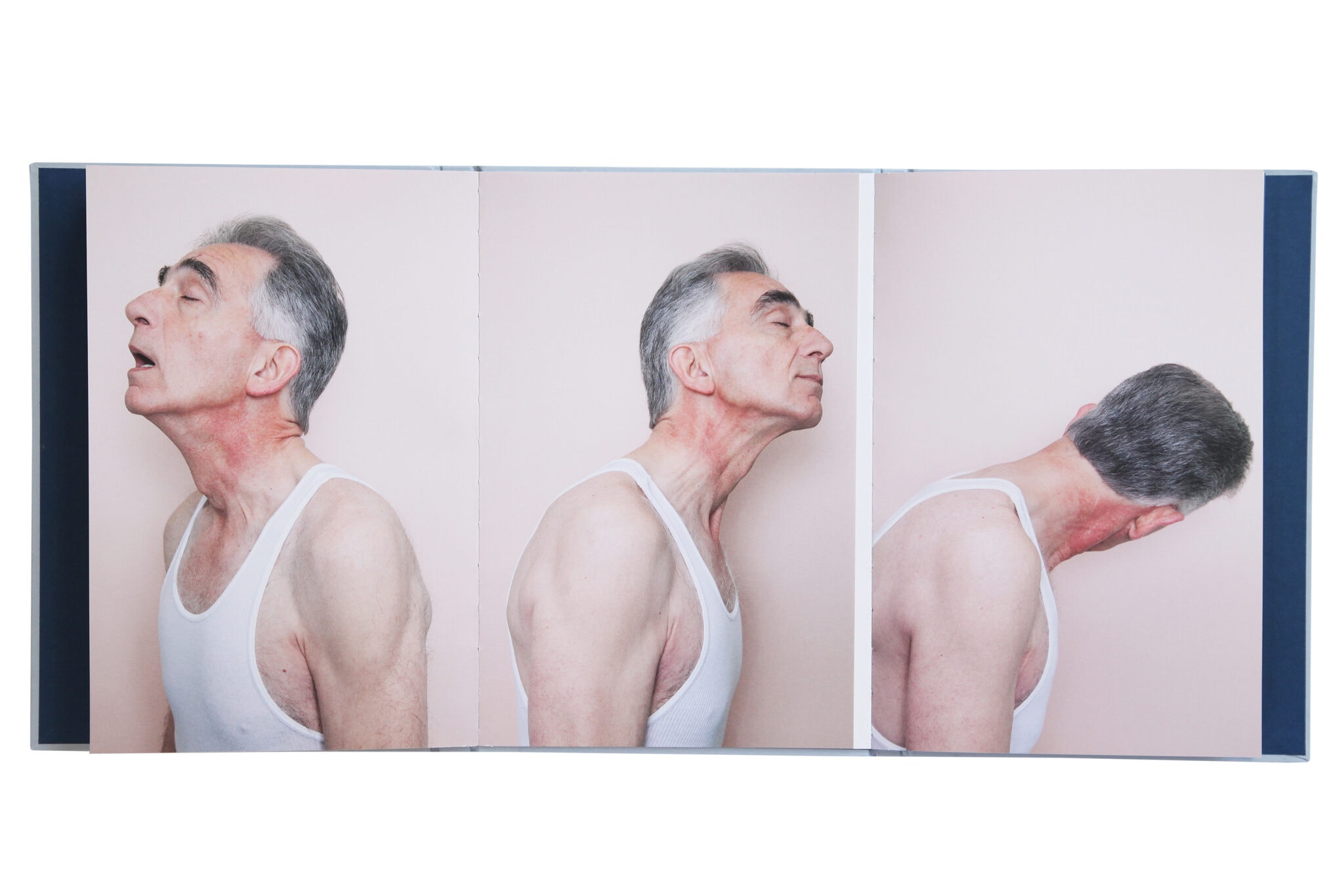

Mariela has at least two very recognized works in the form of photobooks: Moisés, published in 2015, and El Caballo de Dos Cabezas. Representación en Diez Actos, published last year. The first is one of the most exciting photo books published in the previous decade. It is composed of portraits of men of 70 years, the age the photographer’s father could have if he were alive. They are men who share features, and their pictures build a possible image. The book’s layout makes us play to find something in all the pictures and, at the same time, not in any.

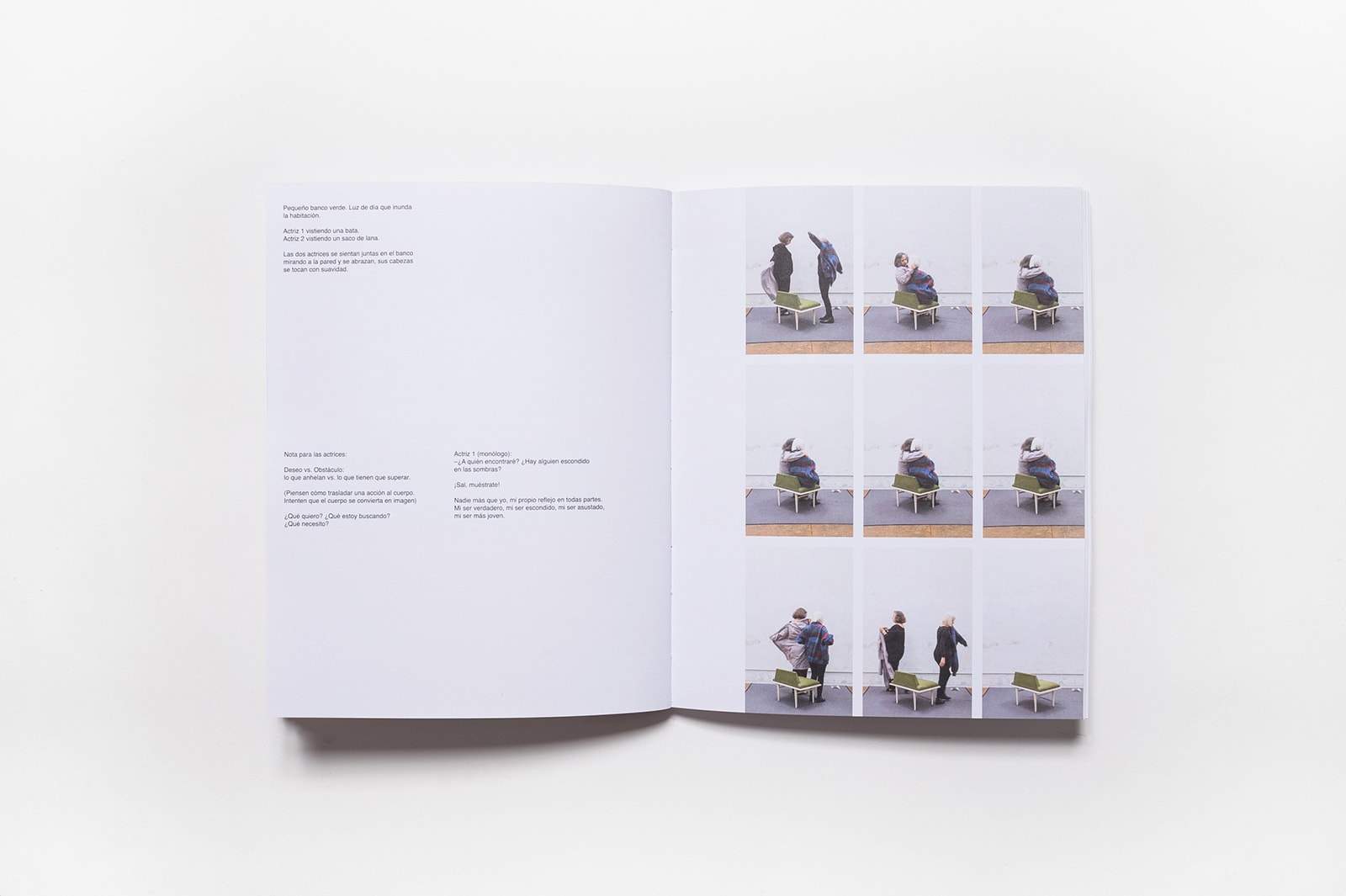

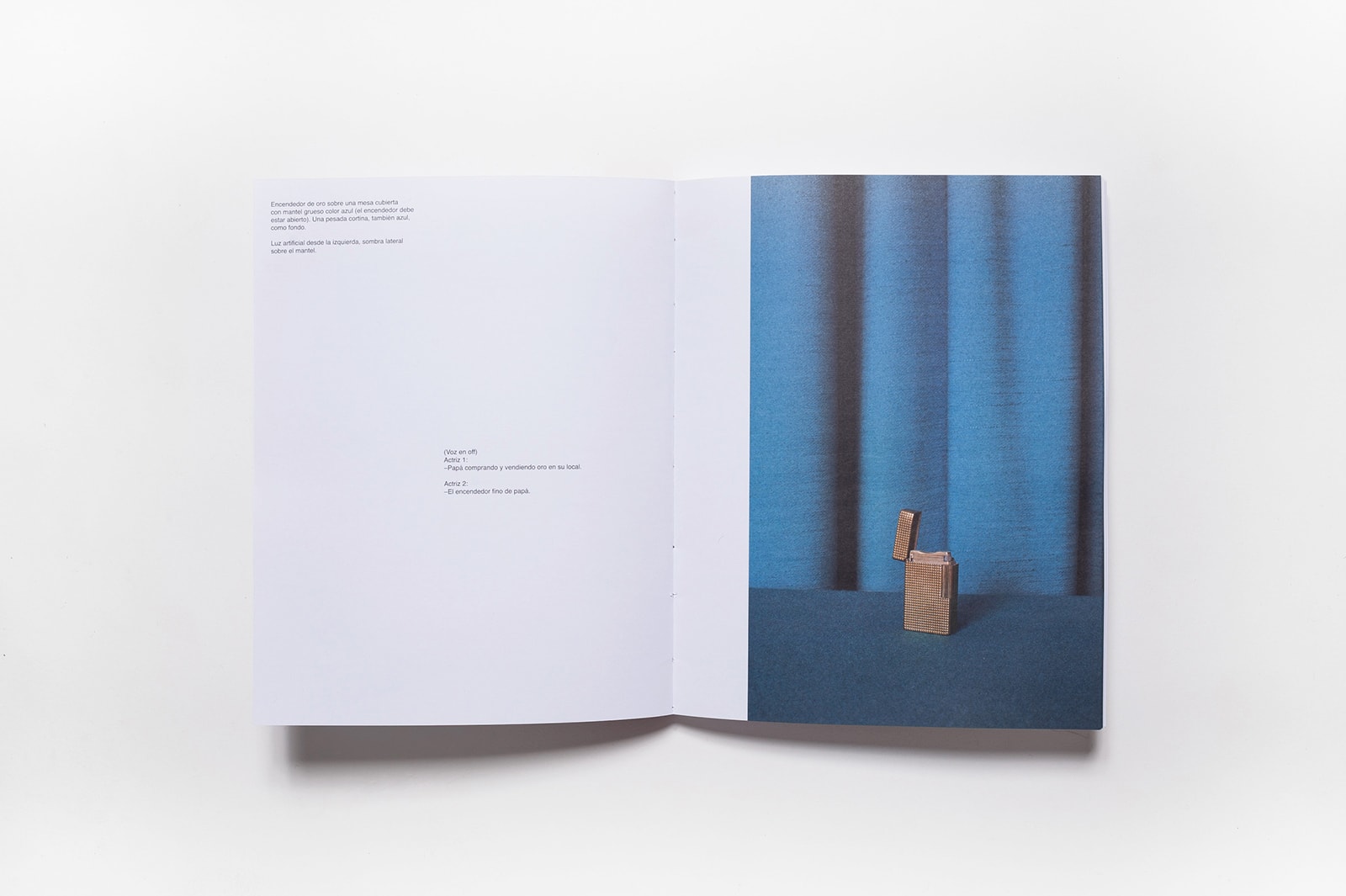

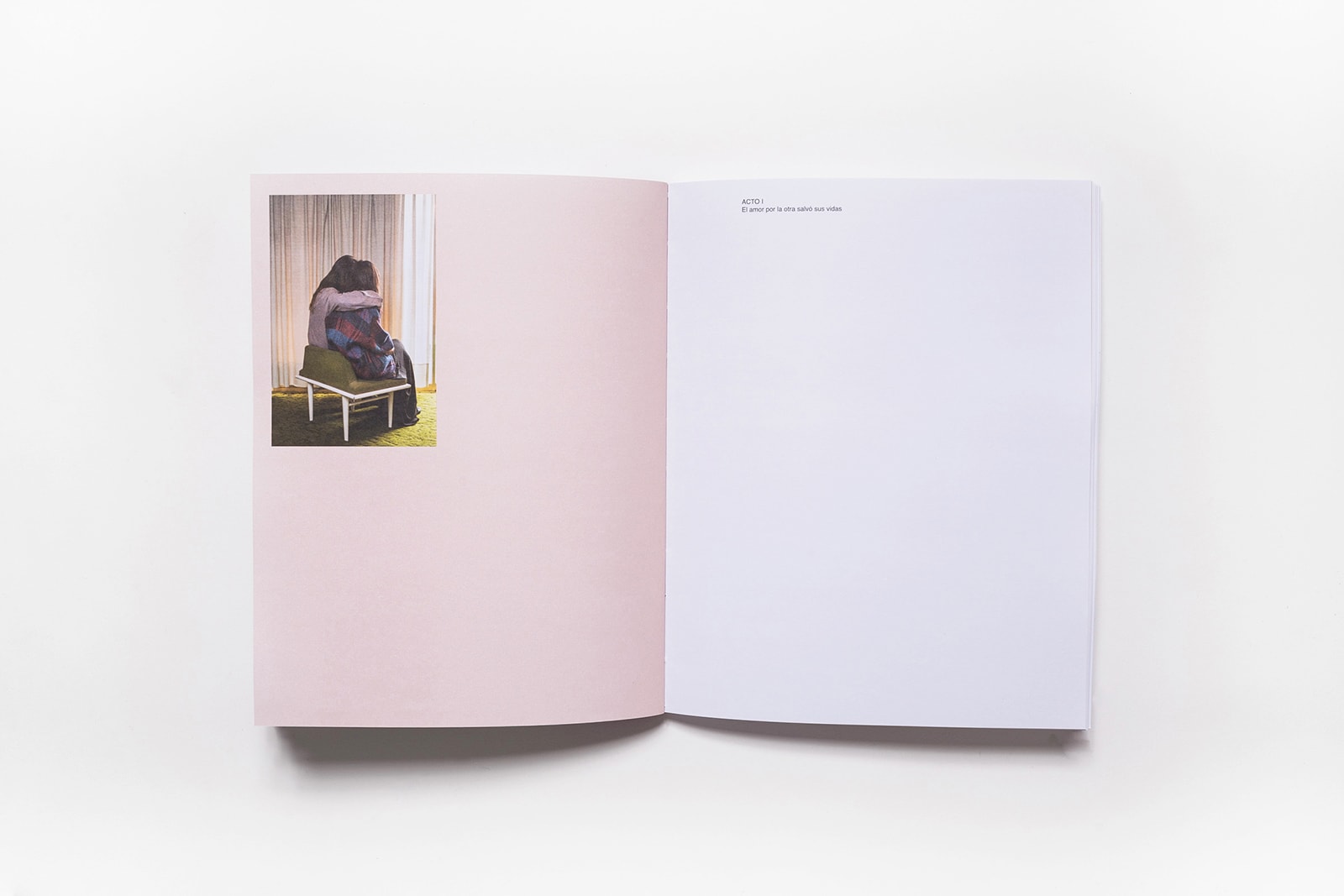

In El Caballo De Dos Cabezas, Sancari revisits a series of the same name she made during her time at the Photography Seminar. It is a self-portraits series with her twin, which the artist turns into a performance in this book. For her, this book is a device. It is presented as a script to direct actors whose bodies will form the images she and her sister made years ago.

The great exploration of Sancari revolves around the construction of meaning and understanding how images work. In her reflection, very close to image theory, language, and feminism, the senses are not closed. Dialogue is only possible from photographs if they open doors, raise questions, and allow imagining. This implies a particular way of thinking about creation: meanings are not given. On the contrary, photographs can be an invitation to create them.

The Chilean philosopher Andrea Soto Calderón expresses this more eloquently in the essay included in the artist’s latest book: Mariela Sancari’s work develops “unexpected ways of seeing, to see what has not been seen.”

Since you started your career in author photography, your works have had a self-referential and autobiographical focus. It’s curious after coming from photojournalism. Why did you take that path?

It arises a bit as a necessity and a bit also in response to coming from photojournalism. In that field, my experience was quite coercive because any attempt I proposed to do authorial work, think from personal narratives, or include autobiographical elements, was frowned upon. In 2011, when I presented myself at the Contemporary Photography Seminar of the Centro de la Imagen, I did so because I knew that was a space where students could explore that image much more freely.

In addition, certain circumstances in my life and that of my twin sister made our plans not be fulfilled as we had thought. I’m talking about the suicide of my father, to whom I refer to my work very openly, and although I would not say that my work is about that, it is a constant.

I approached art with a need to understand and elaborate on things that had happened that were still happening, and I couldn’t find another way to make sense of them.

It was then that you chose the image to achieve it.

Yes, in the beginning, the image and current practices are related to the image. Not only not strictly taking pictures, that is something that I still do, but less. I link the image to thought, body, and action to overflow the notion of an image or what could be thought of as strictly photographic.

A few weeks ago, in an interview with Maya Goded, she said that photography is a path of self-knowledge, but in her case, she travels it in encounters with others. In your self-referential practice, is it possible to think that you travel that path in a meeting with yourself as another?

Yes, everything is mediated, crossed, and even articulated by fiction; it is in that encounter between the image, fiction, and self-referentiality where I see myself. But not literally, it’s not a mirror; it’s not explicit. There is an elaboration: I am looking at myself through it.

I subscribe to the idea that all works are autobiographical. It doesn’t matter if it’s an essay that would seem very distant from our contexts at first glance. I would still consider it autobiographical because it arises from the gaze, interest, and subjectivity of the photographer, the artist.

So I don’t deny the autobiographical component in work, I think about the different ways I can articulate this component. Considering that our work is autobiographical does not mean including ourselves in the images or strictly speaking about our family’s history. Undoubtedly it also means seeing the world, and seeing others, but always from our perspective.

In an interview, you said that you are interested in self-referentiality, not as content but as a way of thinking. How does that work?

For example, my father’s suicide has been present in all of my work, but I do not consider any of my work to be about my father’s suicide. It’s something there that permeates, comes back repeatedly, and has determined my life, my sister’s, and my family’s in general, but my work is not about that. I try to approach self-referentiality as a way of thinking in the same sense that Maya said: as a path of self-knowledge, a form of understanding processes and certain things that have happened in our lives.

I say it in the plural because it’s not just my life. It’s my life concerning others and how that makes sense in specific contexts, situations, and moments. Self-referentiality doesn’t have much to do with that – which seems more like a prejudice than anything else – of looking at our navel as if that were something to avoid. For me, it’s a way of processing, and there’s no way of elaborating our personal and singular stories without understanding them in the context of the community. We exist because others exist too. In that encounter, this thing we’re trying to understand takes on meaning.

“All works are autobiographical. It doesn’t matter if it’s an essay that seems very distant from our contexts. I would still consider it autobiographical because it comes from the photographer, the artist’s gaze, interest, and subjectivity. To consider our work autobiographical doesn’t mean including ourselves in the images or strictly speaking about our family’s history. It means looking at the world, looking at others, and seeing ourselves in that exercise of looking.”

How do you put it into practice in the images?

Self-referentiality is vital in contemporary art, but it’s not always easy to understand. In modern art, self-referentiality is very common, but it’s not discussed openly. Perhaps because of the prejudices I mentioned earlier. Talking about things that have nothing to do with self-referential elements seems more critical. This conception unlinks our stories and extraordinary lives from a larger context; it depoliticizes our existence.

I do it in different ways. Moisés is an example of how self-referential works are not always necessary to feature ourselves and our bodies. I always think that in Moisés, while we see portraits of men who are now the age my dad would be if he were alive, in reality, they are portraits that do not represent the portrayed. In that sense, it breaks or tries to break the relationship with the referent. The pictures try to restore or compose an impossible image of a person who is no longer there. What we have are operations to think about self-referentiality.

In the case of El Caballo de Dos Cabezas. Representación en Diez Actos, I take up the self-portraits I did with my twin sister many years later. So I invite non-professional actors and actresses to embody the images, that is, to make their bodies become those images that my sister and I made. In Moisés, there was a search through similarity. However, I summoned the men I photographed based on a supposed resemblance to my father in El Caballo de Dos Cabezas. Representación en Diez Actos, I try to break that: I work with people of different ages, men, women, and non-binaries.

There is no intention for these people to have any physical resemblance to my sister and me. What is sought is a kind of hypothesis that is not proven: bodies. However, they are socially determined, and not blank canvases can resignify images even from those determinations and the traces that conform to us. In other words, how the body’s operation to become an image resignifies a sense that the idea had before.

It is an attempt to approach others. Becoming an image of mine, my sister again does not try to make a replica. We explore what happens when we reproduce an image from our singularities and how that image changes its meaning. This work is mainly an investigation into the functioning of ideas, about the contexts and conditions that give sense to a photo and the possibilities of changing them.

“The book is often understood as the end of a process. Publishing used to be seen as the culmination of a career. You had to have a certain background to publish. The book still carries notions of fixity, finality, and stability that do not interest me. Thankfully, that has changed. To approach a book as a device, as a script for a performance, is to consider it as part of a process, as an unfinished object. The work happens when the book is activated when it is activated.”

Why the need to revisit and update interests?

When I learned to work with what can be called author photography, I understood that if we filled images with symbols, viewers would be able to decode certain things. And while those symbols allowed for a certain polysemy, in reality, the possibilities were quite limited; that is, we created the meaning of those images a priori.

We were managing how elements with symbolic and affective charges were placed in the image so that whoever saw it would understand more or less the same thing. Now, I can’t continue thinking of images in that way because at least what it does is cut off the dialogue.

My revisitation of this series of self-portraits with my sister and all my research has to do with the functioning of images and with something that Andrea Soto Calderón, a Chilean philosopher based in Barcelona, calls the performativity of images. My exploration seeks to move away from unique and given meanings of images and to imagine ways of enabling new ones.

El Caballo de Dos Cabezas. Representación en Diez Actos, your last book, is where you collect much of this reflection. How did you plan it?

The whole book is presented as a script to carry out a performance. There are the “original” images and the representations. One thing that interested me, related to what we are talking about now, is to present the book as a device. I also explore instances that are not final in the book.

Often the book, as a material object, is understood as the end of a process. In the past, a book publication was seen as a career culmination; you had to have a specific background to publish. Fortunately, that has changed, but notions of fixity, finality, and stability that do not interest me still adhere to the book. Instead, I try to confront them.

Then, to present the book as a device, in this case as a script to carry out a performance, is to consider it as part of a process, as an unfinished object. The work happens when the book is activated, brought to life, and put into action; there, the book stops being the end of something and transforms.

In the book, there is an essay by Andrea Soto Calderón in which she talks about the performativity of images and what is in the subtitle: “from the transition of the fixed image to the performed image.” Could you expand a bit on this idea of performativity?

My way of understanding it is to analyze how images acquire meaning, that is, what are the devices and the contexts that influence what we read: how certain elements are understood, how certain representations are used to say certain things.

Judith Butler analyzes this when she talks about performativity. For her, that is the basis of the construction of sexualities, defined in our societies from repetitive gestures that are entirely arbitrary. This repetition builds fictions of identity but also, in performativity, nestles the possibility of change and rupture. We may have to divert our gaze towards that power, towards the possibility of shaping something. Not only in understanding what the repetitions do at the level of anchoring meanings but also how they can enable an overflow of those meanings.

That also has to do with accompanying what social movements propose. I am interested in making my practice permeable to what we discuss collectively, what we try to understand, and what we share among many.

In that sense, the notion of not posing definitive statements is essential, but of formulating questions, of including doubt in our practices, inhabiting more of those gestures instead of continuing grandiose narratives.