In the Mexican east, in the Costa Chica, there is the afro-mexican territory. This area emerged during the colonization process, when the Spanish brought enslaved people from Africa. They only had few days of rest during the year, which they used for join around and remember their roots. They look those days to practice their customs and traditions that were normally censured in their dailylife.

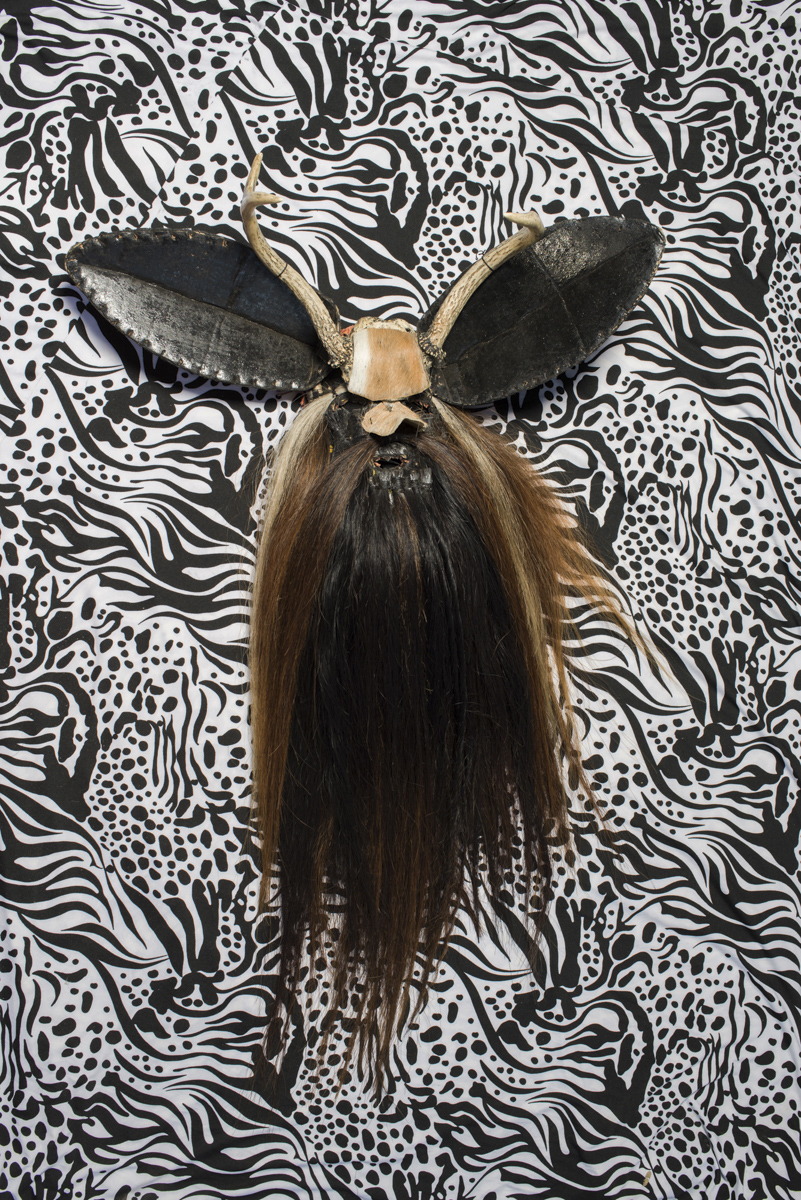

“La danza de diablos” (the devils dance) is a ritual dedicated to the Black Ruja God, to whom the enslaved people pray for their liberation. At the beginning of the dance the god was invocated with respect and reverence to the scream of ¡Urra! There are twenty-four dancers divided in two columns. At the beginning the dancers were all males. But now, even there are few, the females come to dance too.

“La danza de los diablos” is a dance of struggle and rebellion, the manifestation of a cultural force that was brought by the repressed afro descendant people. The church didn’t accept them and didn’t allowed them to dance for their saints or their god. For this reason, they decided to dance for the devil. Like that, they created an identity of the devil that is represented through the masks. The sounds and choreographies that were made are the result of syncretic traditions with an African origin in a fusion with the indigenous traditions, giving rise to the emergence of the first afro Mexican traditions.

Lujan Agusti is photographer and visual artist. She was born in 1986, in Puerto Madryn, Argentina, but she was working in Mexico when the president of United States, Donald Trump, applied the policy of “Zero tolerance.” She had got there to portray religiosity and popular festivals, but she found herself with the drama of the migrant families. And at the border she learned about the Mascogos, the afro descendant community on the northernmost of Latin America.

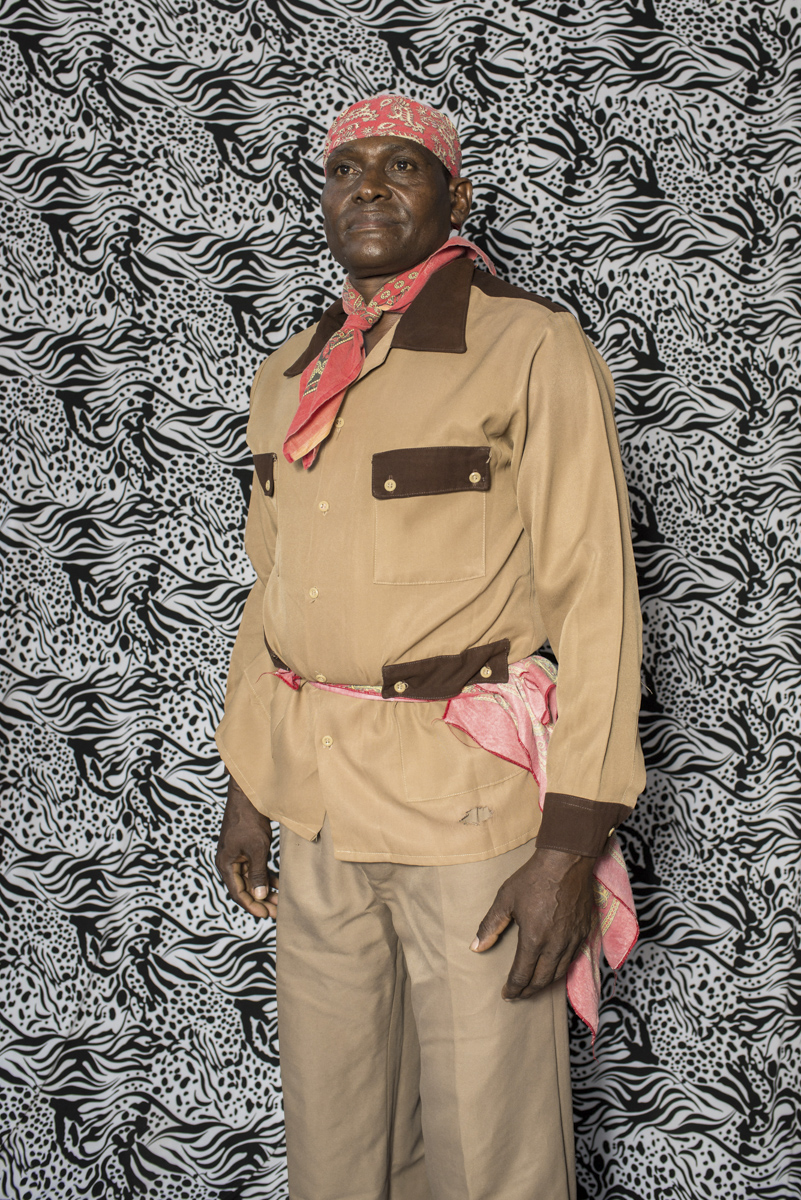

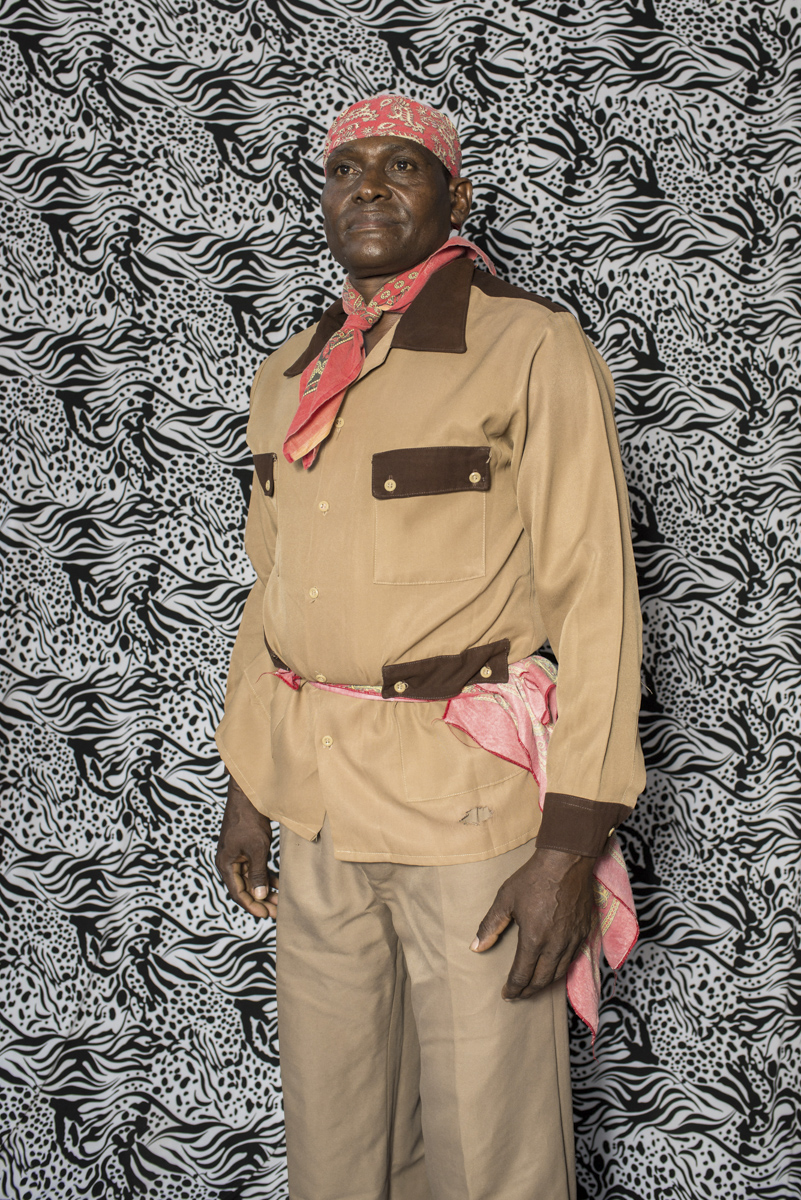

The Mascogos are a community that left behind the U.S. on the middle of the 19th century, running away from slavery. They crossed into Mexico with the condition of protecting the border, between Mexico and the U.S. which was very diffuse. They settle down in the municipality of Múzquiz the Mexican reflect of Texas. Something like the exactly line where Latin America begins. Today, around seventy families live there, they dedicated to planting and raising cattle. They have a reputation of really good riders, and they never give names to horses. Every June 19th they celebrated the slavery abolition on the other side, in Texas. They dress vintage, eat typical foods and dance. “They commemorate their roots”, Luján says .

Before approaching something new, Luján studies respectfully. She nurish herself with some of the questions made by feminisms about roles, and the place that each one occupy to think over their actions and their present. She works with an impetus of a female traveler and the questions of a photographer capable to look her own practice critically.

“It was thought before that the photographer’s position was one of a hero, who comes to reveal the true,” she says. As a female photographer, is not about trying to go hunting: “It is not like you go with a clear objective and you come back with a result, as if it were a capitalist transaction.”

“I believe that there is a form of work that comes around with objectives and results, to being successfull or not. To take the photo. I think that the photographic projects most enriched are the ones that let us make questions. The ones that make us explore, reflect, know and learn of whom comes on the way. It is to understand that the projects moves alone and what we have to do is follow them.”

After that trip and with all those concerns on her back, she returned to southern Argentine to work with her own culture. She wanted to explore some nearly stories in that silent Patagonia. “This is a incredible territory, to me it needs other voices” she says.

There are 9639 kilometers in straight line from Ushuaia to Coahuila. From “the northernmost point to the most austral point, I took a jump that encompasses everything”, she says. From the windy, cold and cloudy end of the word, Luján thinks about photography: “What we do, with luck, is to open some questions that let us understand the world that we live in and to try that our work comes to be a contribution.”

-¿How was your experience in Mexico?

I went to travel and to learn, and in between I applied to a seminar in the Centro de la Imagen, which had an interesting program. I did the seminar, it lasted a year, and from there I began to construct for and I ended up staying there several years more. It was an enriching experience, I learned a lot, it is an incredible country. There I started to work with projects interconnected with the strong presence of the catholic religion on the mexican daily life. Catholicism prevails but when you learn more, you will see the diversity, mostly for me, I came from an agnostic context and I felt interpellated.

I arrived at the border between Mexico and U.S. with the photographer Tamara Merino to do a project for National Geographic and the IWMF. We wanted to portrait what was happening at the border. A great number of latinos with a legal edge were deported to their originals countries and their children were staying in the U.S., as if they were prisoners. A craziness. The initial intention was to work with an indigenous community connected with the Mascogos.

The Mascogos community is disappearing. They live on poverty and their situation is more hidden. Their history is very interesting because they come from U.S. and travel to Mexico looking for a refuge and the Mexican State lets them stay with the condition of protecting the border. Now, a lot of them live between Mexico and U.S. And today, seeing the condition of the border, the youngest migrate to U.S. for study or work and the community in Mexico is getting smaller and smaller.

-How do these trips influence your way of seeing photography?

Mexico opens my mind on a personal level, on a level of experience of my life and my work. Everytime I went to a town, I entered on a different word with traditions, culture, festivals, rituals and a context very nurturing and stimulating for working.

But even thought I feel that mi practice is respectful, mindful and responsible, it can get better. I came to realize that a lot of times that I arrived to a place, even if a have been reading, I arrived with a lot of ignorance, and that makes me doubt about my practice. In that moment I started to feel a necessity to be more responsible, more than nothing in not to believe that because one reads about the community or a place, one believes capable to documented it and to talk about it and for it.

Over time I understood that this was not enough. It is always complex to talk about stories that are not ours and to be the voice of other people. I don’t know if there is a general answer to everything: every case and every story are unique and comes from different needs and forms of being addressed.

-For a lot of female and male photographers it is difficult to think that way.

They are on the defensive line, I think. There is a point where if you don’t start to be aware, you will have to put on an armor and play dumb. I try to be attentive to observe those practices and try not to repeat them. In the context of what corresponds to me as a female photographer, I have processes to not go hunting and I think a lot about that.

I want to be more respectful and careful with the topics that I choose to photograph. A little because of this question of make us in charge of our own privileges and our power position of being photographers. For a lot of time it was though that the position of a photographer was one of an hero that comes to reveal the true, but behind this a lot of times there are bad practices.

-Is this your own reflection or it is made with others females photographers?

I am part of a collective called Ruda Colectiva, we are Latin Americans of varied origins and cultures, and this type of discussion is very common. We talk about very specific issues like white feminism, the place of the afro descendant women on the feminism and that lead us to think about our own works and the roles we play. Somehow what we do, hopefully, is to open new questions that let us understand the word we live in and we try that our works comes to be a contribution.

-With these reflections, has your manner to approach the projects changed?

When I believe that I am going to approach a topic of which I don’t know anything, I try to inform me as much as I can, I read, I talk to the people I with am going to work, with female fellows that can enlighten me.

– Why did you decide to return to Ushuaia?

Somehow that process made me return to the Patagonia to develop some projects and highlight what have to do with my culture. The Patagonia is an incredible territory and I think it needs to have others voices, and that is important to try to coordinate works that generate interest in people that don’t even know where it is. I came to realize that here too, are a lot of silenced problematics.

– What project are you working on now?

I really wanted to come here and I looked for the way to come and work in my business. Certainly I could have find work as photographer but what I really wanted was to do documentary photography. For that I had to generate the possibilities.

I applied a for a National Geographic scholarship and I am doing an enviromental project about peatlands, a typical wetland that occurs in the melting process of glaciers. When the glacier is retried, those peats are formed and that generate important consequences for the absorption of carbon dioxide. When they are extracted, in the process they go down the drain, and are used like combustibles and have other functions.

I came here to develop this project that talks about the connection of the community with the peat bog. A lot of people don’t know what a peat bog is. As for one this a day to day problem, it cost a lot to identify what really matters around yourself. Going out and coming back helps me a lot. Now I want to make projects here.