Photographer Sebastian Lopez Brach adopted two pumas. There are not pets and nor it is an eccentric story: he visits and takes care of them in a reserve where they save their lives. Both of their parents were killed and those two pumas didn’t have any form to learn about survival on liberty. Sebastian’s mission is to feed them, give them medicine, and, above all keep them fit. On visits, he invents games, he hides the food for them to hunt it and he thinks in a lot of waysfor not let them drop on the abulia and the stress. Interacting with pumas is a form of dialogue with the nature and to link with his own animal side

That daily and lovely contact with the wild amplified the questions that Sebastian has always had. He was born in Rosario, on the banks of the Paraná river, the second longest river in South America after the Amazon. Is a brown river that comes from Brazil, cross around Paraguay and Argentina to finally descend to Buenos Aires. Like many people from Rosario, Sebastian grew up around this river of double life: from one shore there is the industrial and harbor city, the second largest of Argentina. On the other side, the islands, the mount and the wetlands, where since he was child knows how to get inside to explore his bond with the nature.

In the pre-pandemic era the plan was to work in different wetlands of Argentina together with the photographer Sofía Lopez Mañan. They have had already gone to the Iberá estuaries in the northeast of Argentina, documenting the flora and fauna of the zone. They had a scholarship of Nat Geo and plan to travel around all La Plata basin.

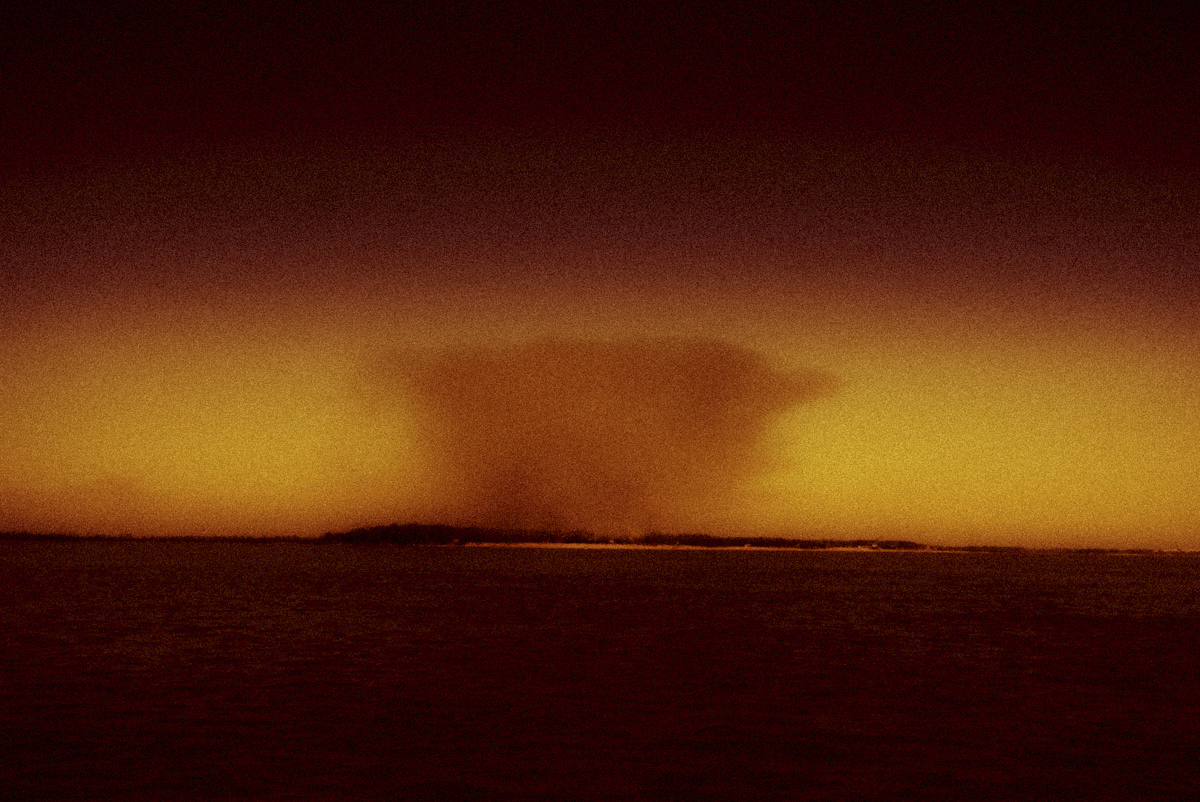

The pandemic immobilized them, but to Sebastian it has a plus: one morning, he woke up and his street was full of smoke. From the other side of the river, his world was burning. In June the fire spotlights in the islands reached to 3.000. A lot of those forest fires were intentional, those were made to increase the agricultural and cattler frontier or to speculate on the sale of land. At the time of this writing, more than 200 thousand hectares have already been lost.

-You were born in a city that grew up in front of the river, it’s visible on your photos. How does this particular landscape influenced your work?

I am very careful with my way of life in relation with the river, in basic and trivial things like the use of industrial washing powder, for example. I always wonder what kind of lifestyle we have, how we live and what impact does this have on the environment. Perhaps that is why it is very confortable to me and intimate for me to work from my relationship with the nature and the environment, with the river, with that water. In the last years I was able to channel this to the social and to work on how the human cohabitates with nature. I try to understand how the human being coexist with flora and fauna, and in particular with Paraná river: what kind of behavior the people around the river have and what they modify. For example, there is a lot of distance between an islander and a city dweller and I ask myself what is the relationship of each one with the territory, the one that ends being part of our identity.

– You’ve been working with the fires on the islands for several months, how did you find out they were burning?

I woke up one morning and it seemed like a tremendous foggy day, but no, it was smoke. I have a constant communication with the families on the island, especially with Oscar, a man I have known since my childhood, and that now he probably is around 65 years old. He is one of this people that have a typical life on the island: he wakes up, prepare some mates, turns on the radio, and watch to which side the wind runs and at the night he does the same: he watches the sunset and the moonrise. He was the first to write me: “they are setting fire on our island”.

– You came with this project about the wetlands and along with the pandemic came the fire. How did that changed your work?

In first place, it touches me very deeply and I had to overpass a lot of strong emotions that to this day I still feel. In the beginning there was a shock: I was working about the wetlands and I ask myself ¿what can I do? Do I change and cover this? When I get myself free I started to commit myself on what was happening, trying to inform to as many people as possible. So I tried to make an image database and started to spread it through networks, because there are lot of mass media that to this day don’t communicate about this topic. Even the president does not talk about the fires.

-You are very used to take pictures of nature, how does the fires changed the landscape?

Not going too far, in my house and in the neighborhood we have very tall trees and by now is normal to see flocks of hundreds herons escaping from the fires and nesting on the city. That’s impressive. I am recording everything from the beginning. I have been taking pictures for six months now and I had the opportunity to overfly the island two times, and I saw how something so green and full of life started to turn out in a black pampa The panorama generated by that destroyed landscape and that black pampa becomes ever wider. The visual field starts to get open, it expands. I have come to see a cemetery of snakes, and you can hear the flames, the rustling of the plants. Is a deafness noise. You can hear the horses, the cattle, the birds burning, trying to escape. That sound of the animals burning is something I will remember for the rest of my life.

-And, how does the human landscape change?

I am working with families from the island and the importance not only of the environment, but the cultural heritage, the customs, their traditions, and the spiritual connection they have with the territory and the water. The fire is reaching their homes. The last Sunday some environmentalists of the Multisectorial Humedales, warned that the fire was reaching the homes of the families in Boca de la Milonga. There is a community of people who lives and were born there. We made a call for volunteers: we found boats, naphta, water, supplies and we managed to save the house of Don Benito, a widower almost 95 years old. The flames exceed the five meters of height. You were four kilometers of distance and you could feel your skin tight, it was a very risky plan and on some sections we had to let the fire advance. It was unstoppable.

– And can you take photos under those circumstances?

Sometimes it happens to me that I see some fellows lifting buckets and running away and I think: do I take the photo or carry on a bucket? That Sunday I was with my camera but I have too my pants rolled up with my foot stuck in ashes and trying to turn off the fire. I put my body as long as it is within my reach, because I think about my daughter too, I try to take care of me. And I believe that before of beeing a photographer I am a rosarino trying to stop the the destruction of his own ecosystem.

It sounds very hard that way of thinking.

I have to be aware and fall on the reality, no matter how hard the blow may be. I don’t know if I will come to see ever again this landscape full of life in its maximum splendor. By now it is a black pampa, a dead landscape. And the river is very contaminated because of the cities from wich it descends and the downspout is impressive, is losing a lot of caudal. If I am honest, I don’t believe that this is reversible, I do not believe that the river will come to what it was. I feel that the river is receding and that hits me so hard. We go back to same thing: the landscape constitute us.