Maíra Gamarra: the power of collective work

Maíra Gamarra is a curator, photographer, and researcher. She has a degree in Social Communication / Photography and a master’s degree in Latin American Studies. Only when she put all of that into play, at the same time and collectively, she understood what she wanted to do. Today she is dedicated to studying, researching, and analyzing Latin American photography. Maíra is Brazilian and the daughter of a Bolivian father, she always had an interest in the region.

For her, the power of collectives — especially when are women collectives — is to enable new debates that were previously hidden or closed. She celebrates questions such as “whom does this image serve?” or “who takes the picture?”, in addition to ceasing to be only white, privileged, and elite men who tell the stories.

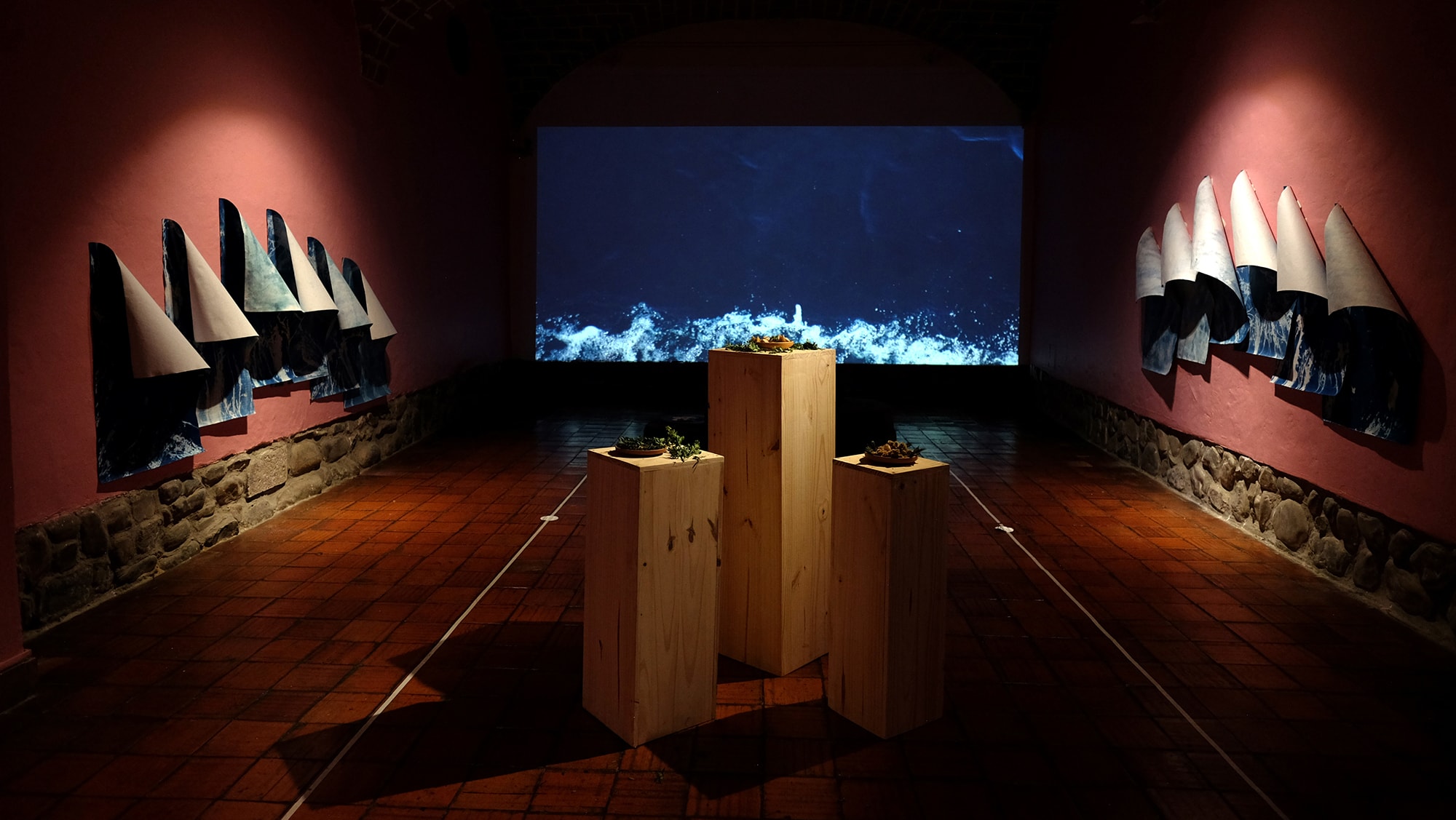

Exposición Ajayu de la fotógrafa Wara Vargas Lara, curaduría Maíra Gamarra y Gisela Volá

How would you describe the current moment of Latin American photography?

I believe we are living in a very interesting moment of democratization of photography, due to the greater access to devices (mainly, the cell phone), as well as a greater awareness of the place of enunciation, or a broadening of the audience. There are more voices. Different people and communities that were long on the sidelines can now communicate through photography, a profession that has always been elitist and masculinized. On the other hand, we see the broadening of debates about important issues such as the “decolonization” of knowledge, practices, and, of course, the image. But, above all, from the imaginary, which is where everything begins. Those kinds of issues have been spurring much-needed changes. But we still need to broaden and deepen these debates in the field.

We also began to discuss and think about what images we make and, actually, what those images contribute to. There are new reflections and discussions about the uses and appropriations of photography, its power and impact, and the immense responsibility we have as creators and disseminators of images. Who does photography? Why do they photograph? Whom do you photograph for? Whom does it serve?

Exposición Ajayu de la fotógrafa Wara Vargas Lara, curaduría Maíra Gamarra y Gisela Volá

Since the middle of the last century, Latin America has assumed a strong political and critical stance in opposition to the hegemonic and colonialist system of our societies, which also operates in the field of photography. Now, we are witnessing a resumption of these positions and greater visibility of issues that were already manifesting the agendas of some groups, such as the black movement, the feminist movement, or the Latin Americanist movement. So today, they have more force and scope, due —in part— to the social, political, and technological transformations that we are experiencing on the continent. This allows us to experience the democratization of photography and communication in general, which is changing the way of telling stories and of those who access them. Just as the discussion from the global south is strengthened, valuing our roots and peoples. That leads us to overcome that discourse that we are the periphery to create new geopolitics in which we recognize ourselves as an important and influential region. In reality, as the region that has made possible the wealth and success of others from its exploitation, which never ended.

We are witnessing a tremendous setback in Latin America in political and social terms. What is happening in Colombia and Brazil. What happened in recent years in Ecuador, Chile, Bolivia, and Venezuela. Photography is affected by all this, we are not on the sidelines of all this mobilization. In addition, photography has its role in all these demonstrations and is used by different forces to convince or give credibility to political speeches, whatever they may be, there is no way to avoid these debates. These and other discussions allow us to have other subjects photographing, telling stories from their points of view, experiences, and territories. Different people assuming their narratives. No longer allowing anyone to stole, exploit, or exoticize their images. No more serving ideas that do not represent them.

And also, we, women who are increasingly aware of race, class, and gender inequalities, occupying streets, political spaces, and jobs that were not allowed before. We are telling or recounting our versions of events, even showing what happens to us from home. It was the space for women, but veiled. So, now we see narratives making the different forms of violence we suffer visible or deepening issues such as motherhood, demystifying it. Changing narratives from our bodies, opposing the “ideal patterns” imposed, from the processes of self-knowledge, autonomy, acceptance, and recognition of our powers. Today we discuss issues that were taboos and we perceive that we are not alone. But it is still a long and slow process.

However, in my research, I observe with surprise that one of the great problems is that many photographers hardly think about the images they produce. They want to photograph but do not want to think and problematize what they do and how we cannot separate the photographic production of all these questions. So there we understand better what the problems of the image are, what the problems of photography are.

Exposición Ajayu de la fotógrafa Wara Vargas Lara, curaduría Maíra Gamarra y Gisela Volá

Do you think that social networks can contribute virtuously in this debate?

Unfortunately, I don’t think so. I am too realistic, although I always try to be optimistic, the truth is that I do not see that it is so. It seems much more complex to me. We live in big bubbles, whether in the real or the virtual. You find many ways to hold onto your beliefs, your worldview, to keep seeing what you want and how you want. I believe that this is related to a long process of colonization and also to that reactionary outpost that we see so strongly in Latin America. Networks are a powerful tool that does allow us to access previously impossible content or keep in contact with people in different parts of the globe, something that, for example, was essential for strengthening the networks of Latin American photography. So obviously, they have their strength and scope, and we cannot underestimate that. We cannot deny that the ways of communicating are changing very fast and the networks now have much more impact and influence on our lives and decisions, but I don’t think it is from hence the possibility of real change. Even because that can be a very dangerous thing to do, networks can also be a tool for mass manipulation. I don’t think the majority of people are aware of how much logarithms affect our behaviors and ways of thinking and relating.

Tejiendo redes en medio del abismo, exposición del I Festival de Fotógrafas Latinoamericanas – FFALA / Curaduría Maíra Gamarra y Joana Mazza

A central axis in your work revolves around the role of the collectives, how did you get to them?

At the end of 2010, a colleague (Ana Lira) went to a photography festival in Turkey. When she returned she decided to gather some photographers to share her experience. It was a very powerful meeting of women who made photography their work and their expression. Then, we went on to meet weekly and in a very spontaneous moment we decided to create a collective, the “7Fotografía”, and a blog to expand for other people the themes and issues that we were interested in putting into perspective, there we began to write and discuss photography.

It was in parallel an interesting moment of the mobilization of the collectives in Brazil. That was between 2010 and 2011, ours has been the first large specifically photographic collective formed only by women. In a very short time, the blog gained visibility and then we transformed it into a website. That demonstrates the power of the collectives because by bringing together people with different experiences, visions, and abilities and also being able to access their particular networks and unite them, the thing gains another texture and dimension. We understood that it was a collective to think about photography. A collaborative meeting between women who find in this space a place for exchange, aesthetic experiences, research, concerns, questions, and reflections. The group initially consisted of six photographers and is currently made up of myself, Isabella Valle, and Priscilla Buhr. But we always seek to act and expand the limits of the collective, with the collaboration of different invited people, further expanding the multiplicity of perspectives on and from photography. We have always been interested in enhancing the possibilities of thinking and acting in a network.

Over the years, we have been forming as a collective of criticism, curatorship, and cultural production, organizing events such as the Mesa7 festival, held in Recife / Brazil and had five editions. In addition to other projects, such as book presentations, exhibitions, conferences, workshops, portfolio reviews, text production, etc. We worked intensively until the end of 2015. February 2016 was our last activity. In 2019 we organized ourselves again to hold an event that should have passed 2020, due to the pandemic we delayed it, but we are still going to produce it. So from that experience, my particular research interest arises, as an individual search for questions that I wanted to delve into.

Tejiendo redes en medio del abismo, exposición del I Festival de Fotógrafas Latinoamericanas – FFALA / Curaduría Maíra Gamarra y Joana Mazza

Why did you choose the field of writing and reflection?

Reflecting on and writing about photography begins with the collective. It is also from that experience that I discovered that research interested me much more than photography. It stimulates me to think about the image and the field of photography, why we do what we do, and the impacts of what we are producing on society. The power of the image is tremendous and I think that we have not discussed it enough yet, we have not deepened discussions. Little by little I migrated and with time, I realized that what stimulates me is to create meeting and reflection spaces (physical, virtual, or even in the text) around photography. I want to make visible the works I am interested in and want to discuss. In addition to encouraging these image producers to become aware of their power and to do so with more responsibility every day.

On the other hand, I am the daughter of a Bolivian father and I always had a strong connection and understanding about Latin America. So, when I started to study photography, my interest quickly turned to the region. I realized that we did not have those regional references, at least here in Brazil (later, I understood that it did not happen only here). At that time, I also got to know the São Paulo Latin American Photography Forum and I realized that there is a whole universe to discover. My research begins very spontaneously, but its development goes a bit because of the need or responsibility that I felt to present to others everything that I had come to know. So, in 2016 I carried out two projects in this regard: the Mira Latina platform and my master’s degree on the Latin American photography network, which we talked about so much in the different editions of the Forum, and I understand with the progress of the research that we could not talk about a single network because there are many networks, parallel and transversal networks that move photography and that is where its power lies.

Tierra Incierta – Maíra Gamarra

Tierra Incierta – Maíra Gamarra