Mangrove forests for Buen vivir

Mangrove forests are among the most biodiverse ecosystems in Colombia. Being between the land and the sea, they serve as a bridge that allows the life of thousands of species of animals and plants in Bahía Málaga, in the Colombian Pacific: it is also home to Afro-descendant, indigenous, and mestizo communities. A home that today they defend from illegal logging and excessive extractivism.

By Juan Arias

“What can I tell you about the mangrove? Well, since I was tiny, it was my mischief; I was going to study. My mother thought I was in school, and it was a lie. I was out there hanging out with my brothers and sisters, and the mangrove is a huge emotion for me. It is something that has no meaning. One imagines it but can not measure the greatness of the emotion that the Raicero (the forest) can give us”.

Like this, Liliana Salazar responds, whose livelihood comes from extracting mainly a mollusk called Piangua (Anadara Tuberculosa) in the forests of Bahía Málaga in the Colombian Pacific. This leader, together with other women who live in the collective territory of the Consejo Comunitario (Community Council) of Bahía Málaga – La Plata, created an association of the Piangueras to continue working without damaging the mangrove forests. That is very important to them: the mangrove is a tree highly resistant to salt water; it prevents erosion and minimizes the impact of waves while providing protection and habitat for multiple species. In times of climate crisis, the Piangueras of Bahía Málaga know the importance of balancing the conscious exploitation of their resources and conservation.

“We were children, and my mother took us with her so as not to leave us alone in the house, and that’s where we learned to work the shell. I was about six or seven years old,” says Patrocinia Torres, another woman living in the collective territory. Since she was a child, her life has revolved around the extraction of Piangua, the source of subsistence for her entire community. For the more than 150 families that live in this forest, the Piangua is an easily accessible product, a source of protein and income due to its rapid commercialization.

Matilde Mosquera and Ana Cristina Murillo, women piangueras from the community of La Plata,

Bahía Málaga.

Matilde Vergara and Auranelly Días, women piangueras from the community of La Plata, Bahía Málaga

Aerial view of Bahía Málaga

The Bahía Málaga – La Plata Community Council is the result of a struggle of more than 400 years in the territory by Afro-descendant communities. It was only recently that they managed to extend the collective titling of the land to a total of 38,000 hectares, thanks to the commitment of its inhabitants to conservation. “It was conserved not to attract attention; it was conserved to continue living here,” says Saúl Valencia, current legal representative of the Community Council and one of the young leaders who represent the generational replacement. In the absence of the State, the leader admits, they have had to rethink different sustainability models. The premise is simple: “To build a dignified life to continue living in the territory.

The problem is that this territory, attached to the district of Buenaventura as a rural and dispersed population center, according to the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística – DANE is one of the many that double the figures of deprivation of opportunities for its inhabitants: illiteracy 14.1%, low educational achievement 48.3%, long-term unemployment 43.5%, among other worrying statistics.

Ana Cristina Murillo, also a community leader, will never forget the sentimental value these mangroves have for her and her family. When she was eight years old, at this same time of year, she caught about 40 dozen Pianguas; with this, her family made a living. Murillo hopes that the new generations of her community will retain this practice but at the same time will be able to achieve the progress that was denied to her, her parents, and her grandparents.

Matilde Mosquera walks with her gear to fish and make measurements on the piangua sharecropping in La Plata.

Piangueras women group return after a day of collecting and measuring the Piangua resource.

Rooting to the mangrove forest generates a direct nexus of coexistence with the ecosystem. And it is from this nexus that Santiago Valencia, leader and tour guide, affirms that the struggle does not stop. Extractive activities such as mangrove logging make the territory changeable and bring new challenges. Liliana Salazar knows that the impact is not limited to cutting the trees but also the damage caused by pollution from this extractive activity.

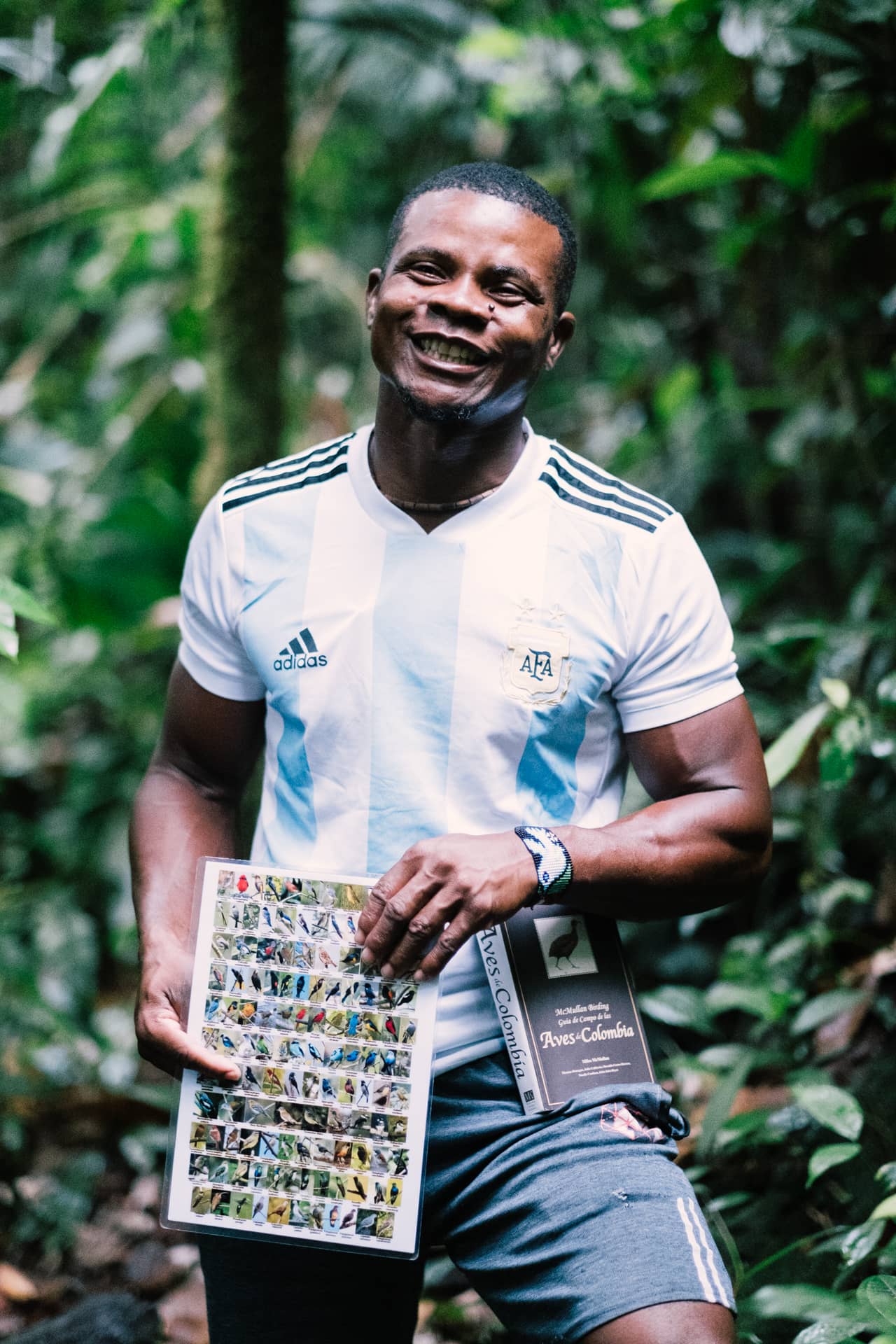

Logging has been controlled in the collective territory, despite being a potential source of income. It is by raising awareness that families have been able to migrate to other sources of income that do not impact the ecosystem. Yeferson Martinez, forester and bird-watching guide, says that he used to see wood with his father in the past. Today, thanks to the Community Council, he has minimized this activity’s environmental impact by cutting trees that take hundreds of years to replace. Now the community seeks to practice other forms of subsistence in harmony with the territory, such as environmental services and ecotourism.

Yeferson Martinez, former commercial sawyer and now birdwatcher in the community of Miramar.

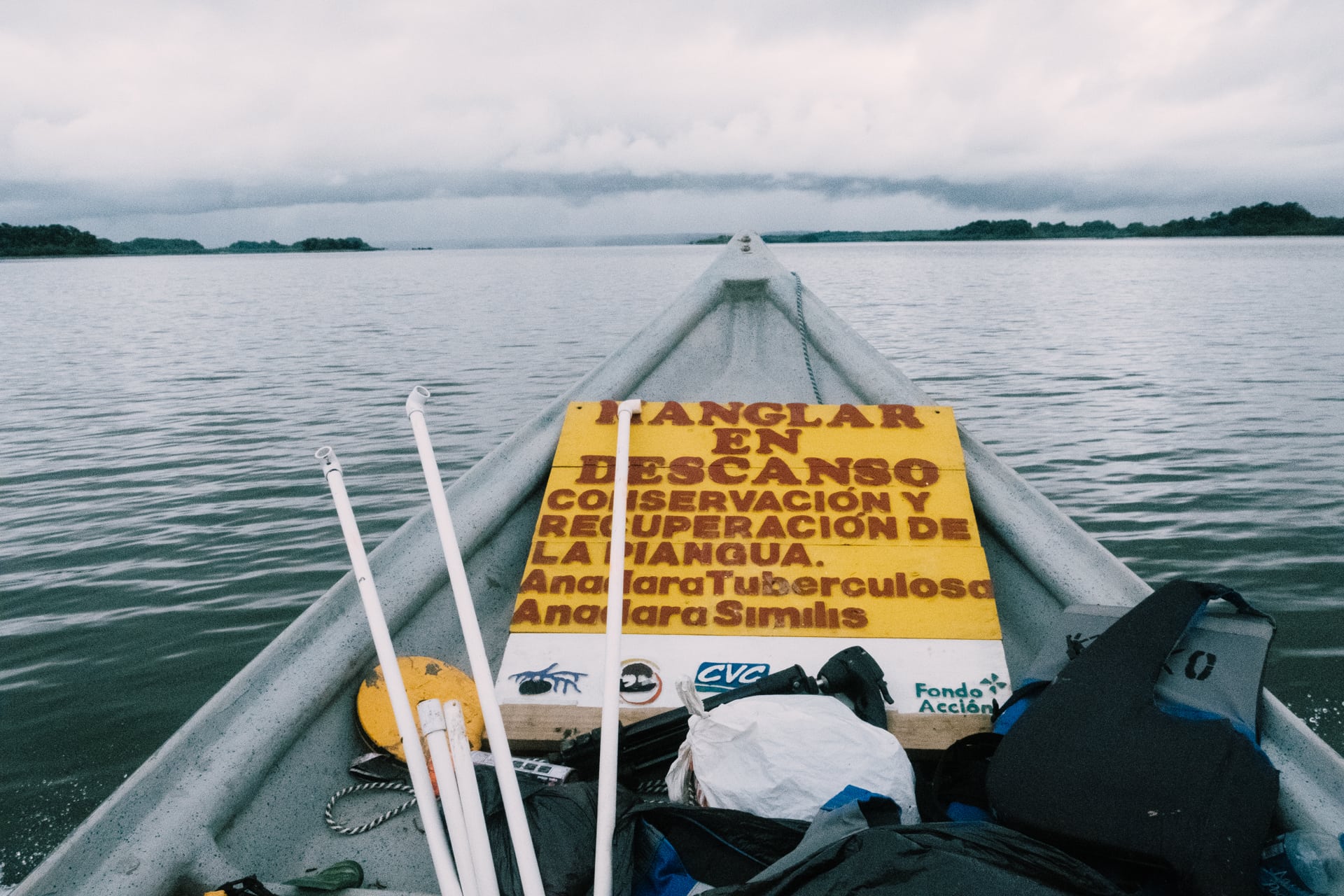

In addition to logging, this community faces an imbalance in the ecosystem generated by the excessive extraction of Piangua. “We are taking a lot for outside people, and they are taking a lot of the small Pianguas. That is destroying the mangrove,” says Patrocinia, whose concern coincides with that of the community: given the depletion of these mollusks, voluntary closures are necessary to conserve the resource.

The pianguimeter. Research and conservation tool developed jointly by the Universidad del Valle and the community of Bahía Málaga to protect the pianguimetro resource.

Matilde Mosquera is the legal representative of the piangueras women of Bahía Málaga. She assures that this association benefits her and unites the four communities. With 161 members, all carry out the fishing activity, respecting the guidelines created through community processes and internal regulations.

All this process has had women’s leadership: they have empowered this initiative with their vision of conservation under the premise of living and subsisting. “Whoever comes to take advantage of the resources must submit to the internal regulations, which are a minimum of ten years of healthy coexistence. They also have to control the territory for ten years to be able to declare themselves as beneficiaries of the territory and be able to use it sustainably,” says Saúl Valencia, representative of the Community Council. “In the Pacific, there is no such regulation through ordinary law; they are internal regulations designed by the communities to exercise governance over our territory.”

This sign is part of the community’s initiative to indicate to other community members that the mangrove is under voluntary quarantine to encourage the growth of the Piangua.

Matilde Vergara contemplates the landscape of Bahía Málaga as she walks to the mangrove swamp. She divides her time between the Piangua activity and raising her children.

Liliana Salaza and Matilde Vergara take shelter from the drizzle, which comes and goes intermittently this time of year in Bahía Málaga when they go out for pianguar.

La Plata Community Council is an example of coexistence with the biodiverse territory where long-term community cohesion processes play an essential role. They are the basis for external governmental and private programs or initiatives to have the necessary conditions to guarantee their continuity. “Today, women in Bahía Málaga know how to value what we have,” says Auranelly Díaz. “We thank our parents who taught us that we had to take care of it. If today we have for our children, it was because they conserved first.”

For her, the responsibility key of the community today lies in an ancestral struggle for a good life. And she demonstrates it in a way that summarizes that bond rooted in their culture: singing.

*This report was made possible thanks to the Environmental Journalism Fellowship, which is part of the United for Forests initiative led by the Foundation for Conservation and Sustainable Development (FCDS) and the Norwegian Embassy. And with the support of the United Kingdom and European Union embassies and the Andes Amazon Fund and Rewild.