Memories in the shadow of a dictatorship

In 2023 it will be 50 years since Pinochet’s coup d’état: an event whose aftermath is still perceptible in the social outburst that shook Chile in 2019. Using newspaper clippings, photos from the family album, contemporary portraits, and snapshots of recent demonstrations, Eric Allende explores the weight that the political history of his country has had on his family. With Project 226, he has set out to reveal how disappointment over a future that never came-or over the unfulfilled promises of the neoliberal model-has shaped the lives of several generations of Chileans.

By Alonso Almenara

Among Eric Allende’s earliest memories is a photograph of his grandfather Alfredo greeting Salvador Allende. “My uncle worked in a factory that the president visited, and that’s where he met him,” says the photographer, who, despite having the same last name, says he is not related to the former president. “I remember that photo from when I was a child: it was always in the house, in a good place, proudly displayed.”

For a long time, Eric lived with his maternal grandparents on the outskirts of Santiago, at number 226 of a street called Lastenia. They lived an hour from the capital, where the urban area ends, and the rural area begins. “It was a very poor place in the seventies, pure countryside. But there were still cells, as they called them”. He refers to armed groups that opposed the Pinochet regime after the military coup against Allende in 1973. Although he understood, from an early age, that his whole family was leftist, politics only concerned him in adulthood. After all, they didn’t talk about these issues at his grandparents’ house. To the point that Eric spent the first twenty years of his life completely unaware of an essential part of the lives of his closest relatives: militancy. “I couldn’t imagine my mother with a gun,” he says.

It changed when Eric began studying photography in high school. “One day, I was asked to do a journalistic assignment, and it occurred to me to deal with the period of the dictatorship. So I interviewed my mom. It was powerful because I found out things I never imagined about her: she told me that she had been part of the Communist Youth in the early eighties”. And he adds: “One day they blindfolded her and took her to a secret place, in a forest, she doesn’t know where. That’s where she learned to shoot.”

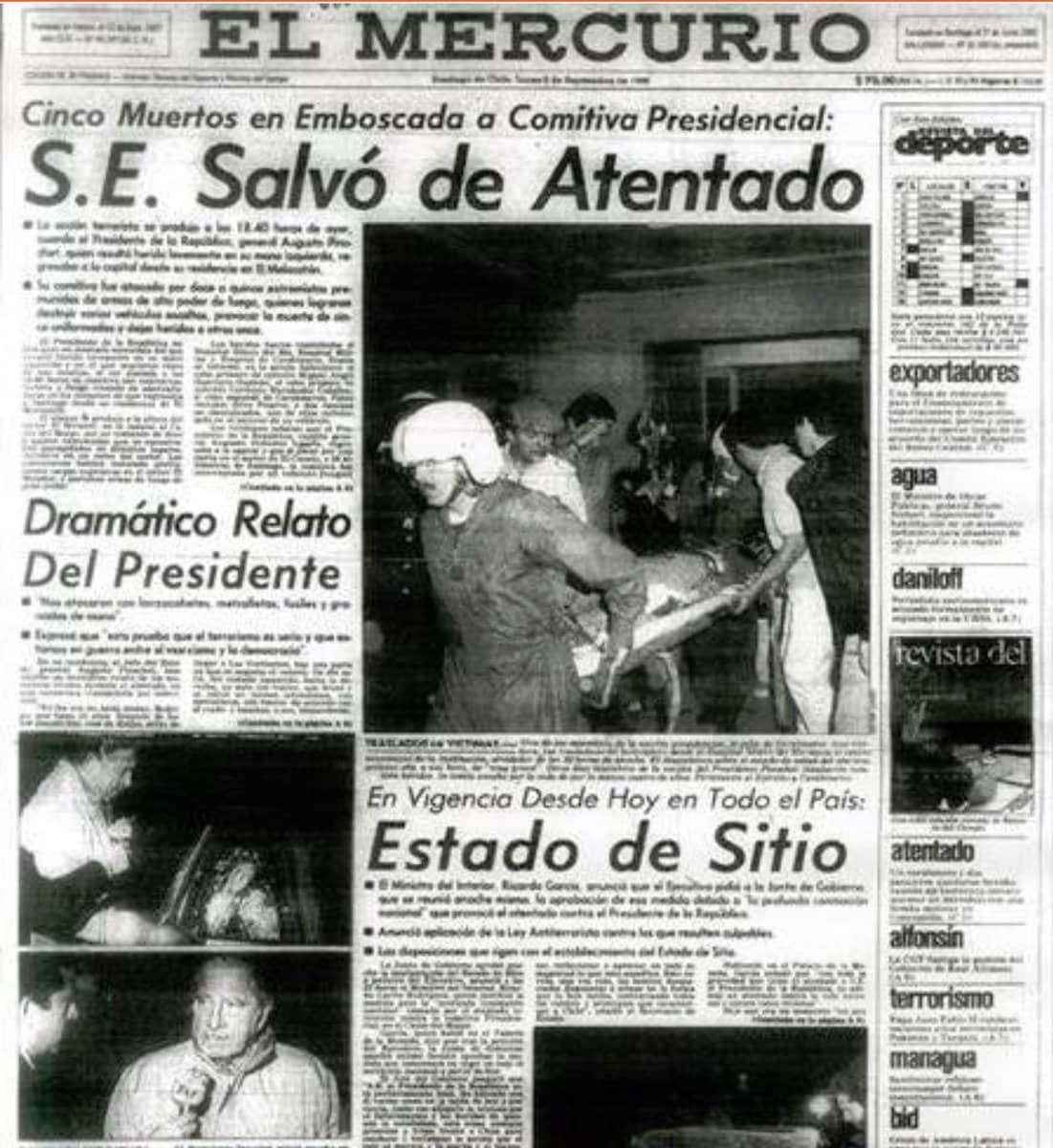

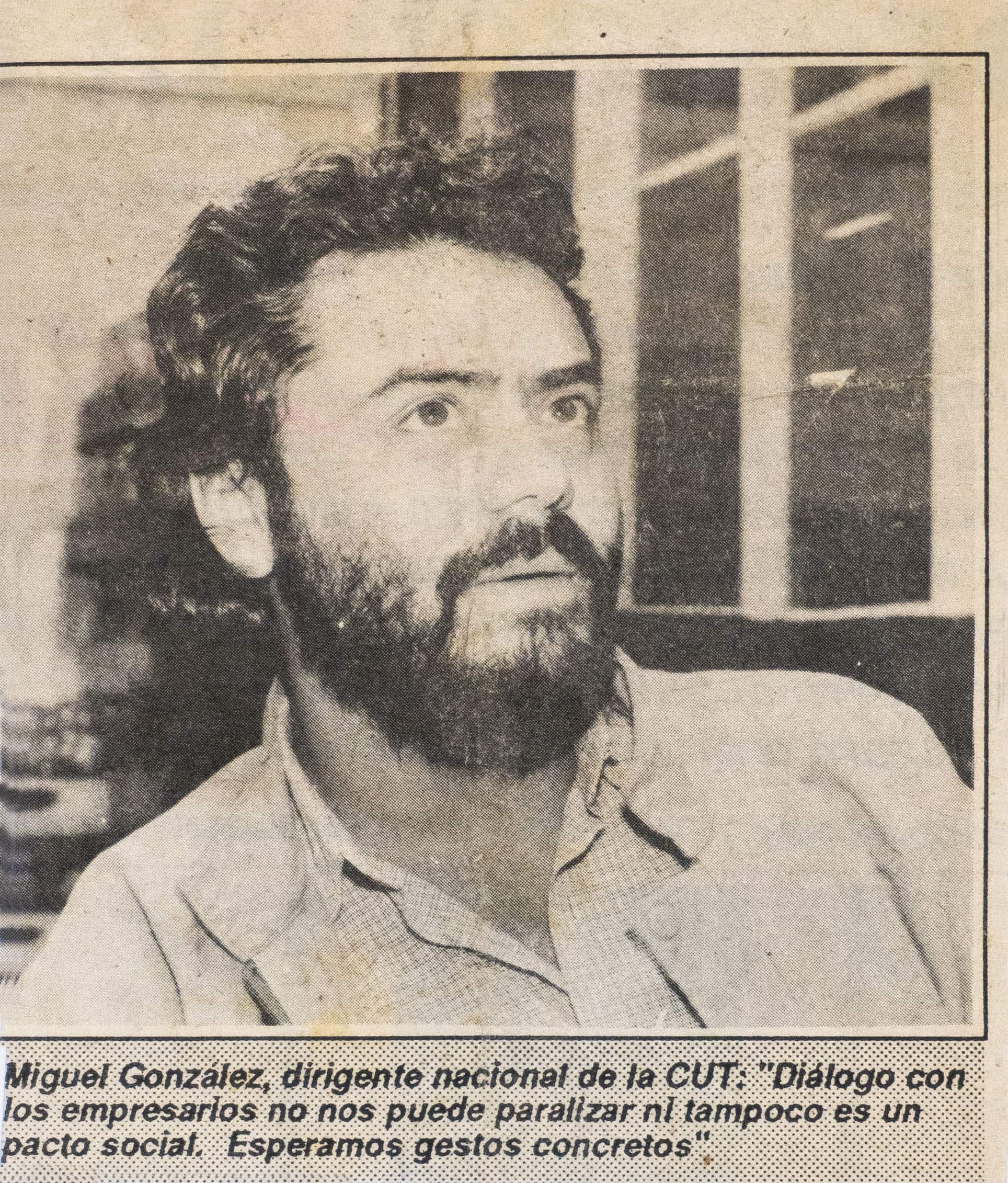

Eric learned the same day that his maternal grandfather had worked in the reconstruction of La Moneda Palace after the attack that ended the life of Salvador Allende on September 11, 1973. Also that two of his uncles had gone to Russia to study. “I have some newspaper clippings in which my uncle Miguel appears: he was from the communist party, he was a union leader. He was arrested a couple of times; nothing serious, fortunately”. Suddenly he understood that his whole family had actively opposed the military regime.

Thus arose the idea of 226, a photographic project that reconstructs the history of the González-Muñoz family -Eric’s family on his mother’s side- taking as a central element the coup d’état that reconfigured Chilean society five decades ago. An event that, in a certain sense, does not lose its contemporaneity since it was the bloody rite of initiation with which the first neoliberal regime in the world was established, as Marxist theorist David Harvey points out.

“I was interested to see what they did apart from fighting: they also had happy moments because, as a family, they held back. And to those old images, I added photos of the 2019-2020 outburst I took myself. Ultimately, it’s about the same process, a long process that starts in the seventies. Because although the dictatorship ended, social inequality continued. We fought for the same problems they did: better health, housing, education.”

For the Chilean photographer, documenting the violence that sealed that transition is still essential: his generation cannot afford to forget state terrorism, arbitrary detentions, censorship, and disappearance. But his work takes a different route: he focuses on small personal stories, the daily struggles, and silent tragedies that were also part of the resistance to Pinochettism, as well as the disappointment, the immense frustrations brought by the return to democracy.

“The dictatorship lasted so many years that not everything was a struggle; there were also family moments. I was interested in exploring how my family lived that time, using the few photos I have been able to rescue from that process,” says Eric. “I was interested to see what they did besides fighting: they also had happy moments because, as a family, they held back. And to those old images, I added photos from the 2019-2020 blowout I took myself. Ultimately, it’s about the same process, a long process that starts in the seventies. Because although the dictatorship ended, social inequality continued. We fought for their same problems: better health, housing, and education.”

He didn’t expect it would be so challenging to get information: his uncles still find it difficult to talk about that time. “I don’t think they feel shame, but maybe they want to forget it. Because they all made sacrifices.” Eric comments that although all his relatives fought in a dictatorship, none knew precisely where the other was, as they belonged to different cells. “They had to burn books and pamphlets because the police raided them. At one point, they told me that they took all the men in the neighborhood. One of my uncles was detained for about two months”.

No one disappeared among the González-Muñoz family, but the harassment of the forces of law and order accompanied them for years. “They told me that Rubén, a person I knew from the neighborhood, was detained here in Cerro Chena. They had him tied to a post for two days, naked, and he heard how they raped a girl. These terrible situations must have happened a lot. And they are strong. When they told me about it, I wondered how you get back on your feet after living through such a tough experience.”

Among his most immediate family members, the story of his aunt Juani affected Eric the most. “She had to sacrifice raising her daughter to concentrate on fighting. She told me it was tough to be a union leader as a woman then. It was a world of macho men. So one of those great sacrifices was raising my cousin, who had to be left with a neighbor, an aunt, or other relatives to take care of her. Their goal was to overthrow Pinochet so my cousin would have more opportunities than she had. Perhaps because of that difficult situation, my cousin started using drugs at 14”.

And he adds: “I believe this story has not only happened to my aunt but to many families in Chile. Families who perhaps, thank God, did not have people arrested or disappeared but who made great sacrifices to fight against Pinochet. And I think I also understood this because I had to live through the process of the social explosion. Unfortunately, there were many wounded, and those are the best-known stories, but there are many other stories of anonymous people who lost a lot to assert their rights and seek a better country”.

When mass protests broke out in several Chilean cities at the end of 2019, the fierce repression by the government of Sebastián Piñera brought reminiscences of the state violence the country experienced in the 1970s and 1980s. For the González-Muñoz family, the connections between the two processes are transparent. “It is true that the problems had been accumulating for many decades and that the different governments were not and were not capable of recognizing this situation in all its magnitude.” Said Piñera in a speech in which he lamented the 18 citizens’ death at the hands of the forces of law and order.

With 226 -a project that will soon become a publication-Eric Allende seeks to contribute to ensuring this barbarism is not forgotten. And the sacrifices of those who have been fighting for decades in Chile for the exact causes can find an echo of solidarity among the new generations.

“When the referendum took place, we talked a lot. After being turned off for many years, it is as if they have become active again. Because when the dictatorship ended, everyone imagined a better future, and in the end, it was not like that. Chile continued to be a right-wing country, many things were privatized, and social issues did not prosper”, says Eric. The disappointment, in his words, “was gigantic.” But as terrible as the repression was, this new process, still underway, is for the Gonzalez-Muloz family a reason for hope. “They told me they liked seeing how the young people had lost their fear. Then they supported everything they could. We went from not talking politics to marching together; we joined the protest.”