Memories that the dictatorship could not erase

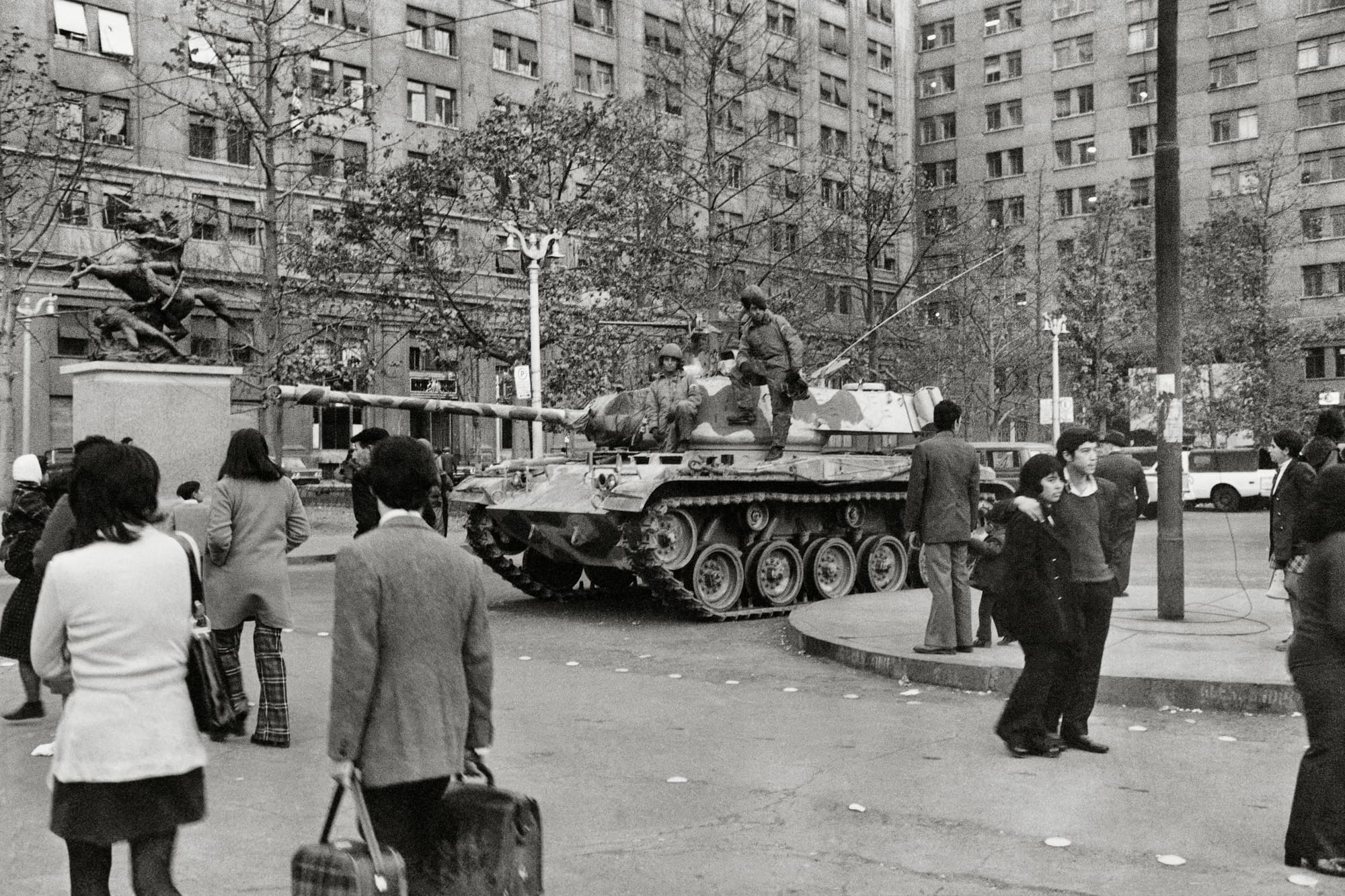

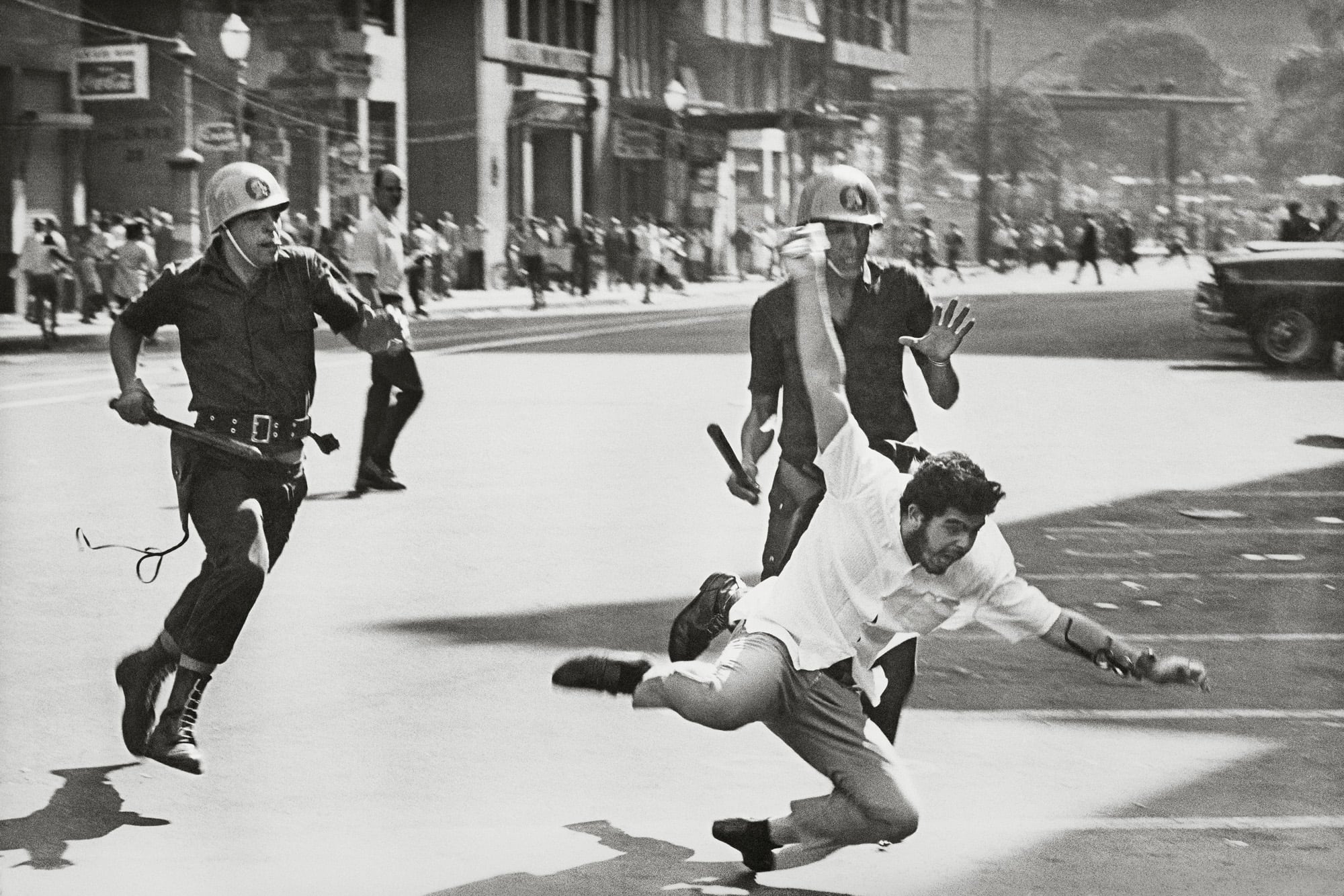

Half a century after the military coup in Chile, the images taken in Santiago by Brazilian photojournalist Evandro Teixeira are coming to light. Sent by Jornal do Brasil, the vast majority of his photos were censored by the military government, which controlled what could be published in the Brazilian press since the late 1960s. Organized in an exhibition about Teixeira’s work, the images deepen the understanding of what happened in the Chilean capital in September 1973, including the death of poet Pablo Neruda, whose causes are still debated.

By Miguel Vilela

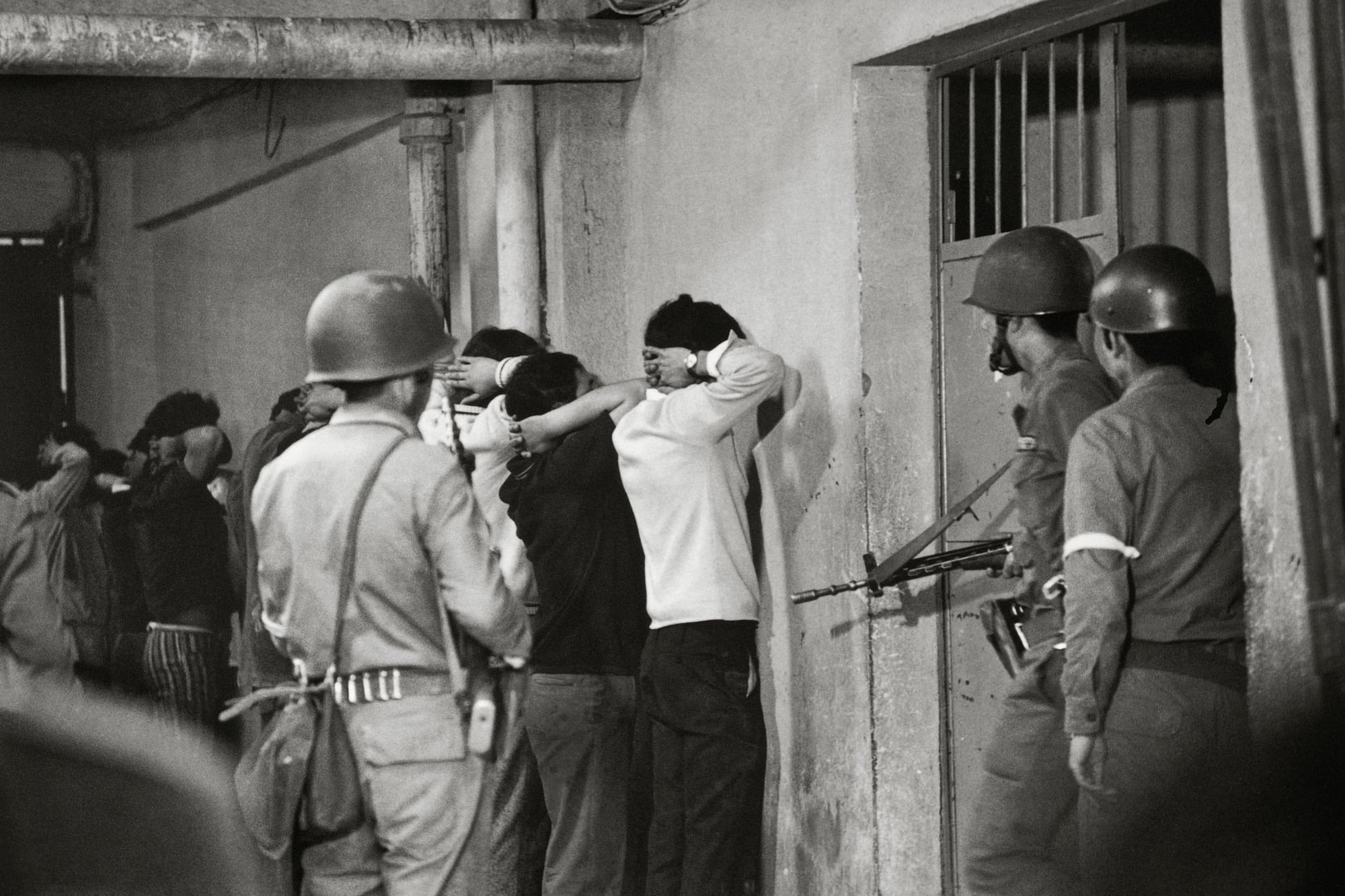

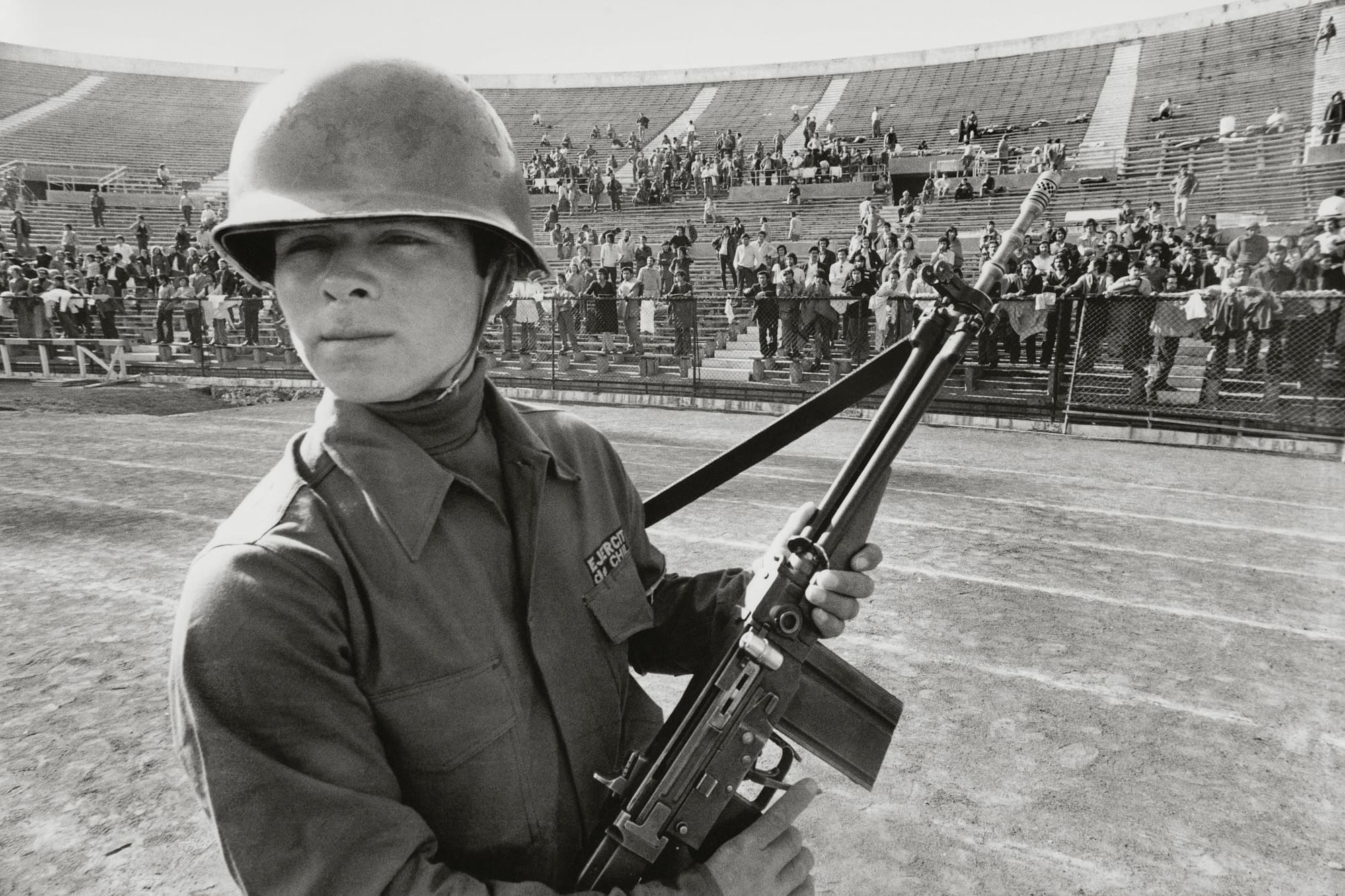

“The colonel took the journalists to the National Stadium to say that everything was fine, that the students there were being well treated, and that nothing was happening to those boys,” photographer Evandro Teixeira recounts about his experience as a photojournalist days after the military coup perpetrated by Augusto Pinochet and his accomplices in Chile. “But we knew terrible things were happening.”

Teixeira arrived in the country with international correspondents who attempted to enter shortly after the military coup on September 11, 1973. However, with borders closed, they were held between Argentina and Chile for nine days and only managed to land in Santiago on September 21.

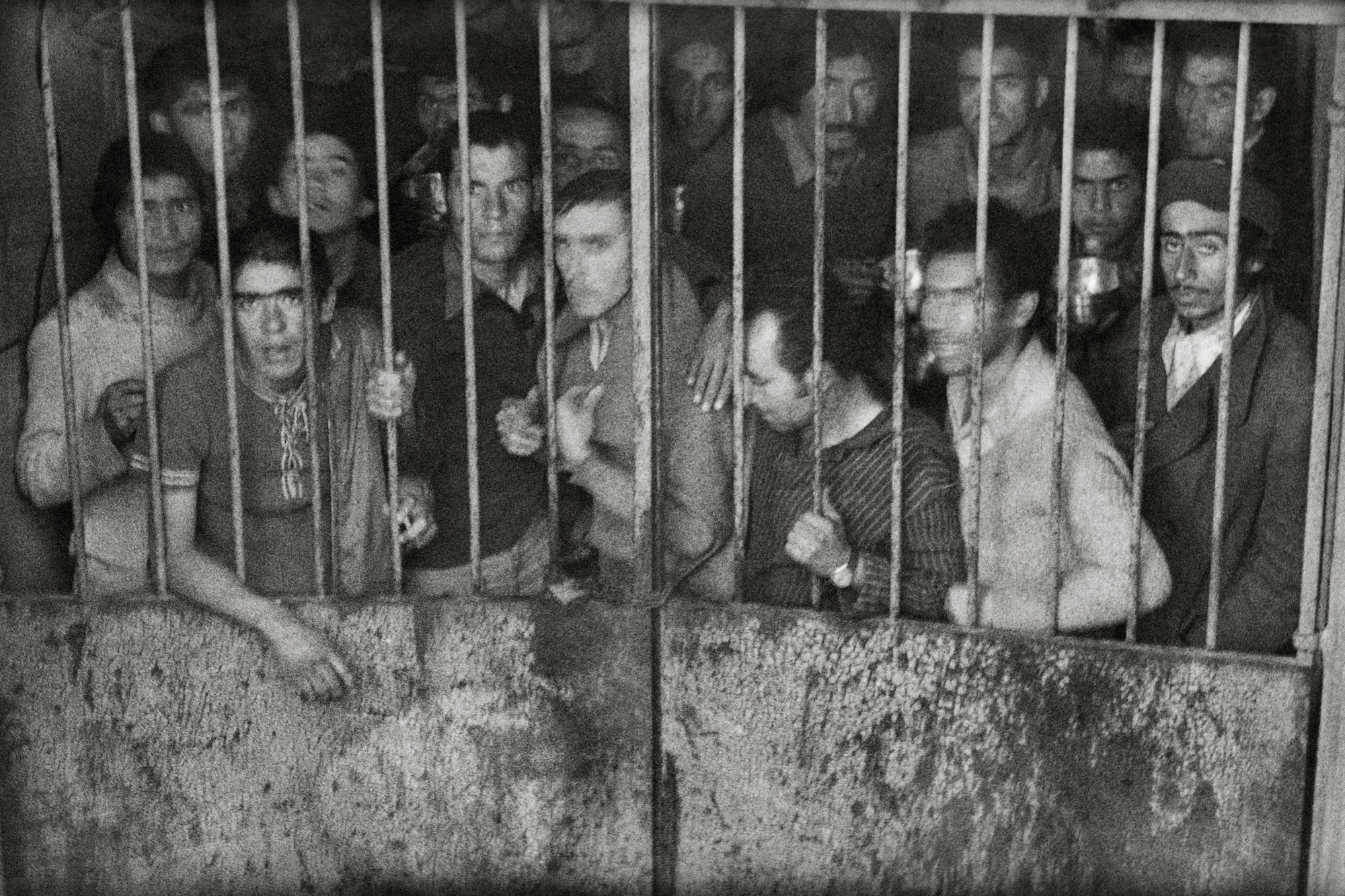

In the capital, Teixeira and his colleagues participated in an official visit to the National Stadium of Chile, where political prisoners were held, and reports of human rights violations emerged. The military intended to refute complaints of mistreatment and show that political prisoners were being well cared for. But that was not what Evandro Teixeira documented.

Due to the military’s disorganization, the journalists arrived at the same time as a truckload of prisoners. Teixeira, who knew the stadium from covering the 1962 FIFA World Cup held in Chile, managed to evade the group and access the underground area. There, he saw young students crammed into cells, rifles pointed at them, hands on their heads, facing the wall. “I ran down with the camera in my hand, and suddenly I saw that gate, with the imprisoned students suffering, and then those others leaning against the wall. All of them were shot,” he said in a conversation with journalist Dorrit Harazim during the exhibition “Chile, 1973,” which was displayed at the Institute Moreira Salles (IMS) in São Paulo until July 31, 2023.

Despite the horror witnessed by Teixeira, few of the images he captured were seen at the time. Out of the more than 300 photos he took over about 20 days outside Brazil, only seven were published in Jornal do Brasil, the outlet he worked for. After all, Brazil was also under strong repression. Censors appointed by the military government monitored newspaper production from newsrooms. They vetoed any narrative that went against the interests of the dictatorship and the collaborating neighboring countries, some of whom are said to have included Brazilian torturers with electric shock machines at the National Stadium in Chile.

The Death of the Poet

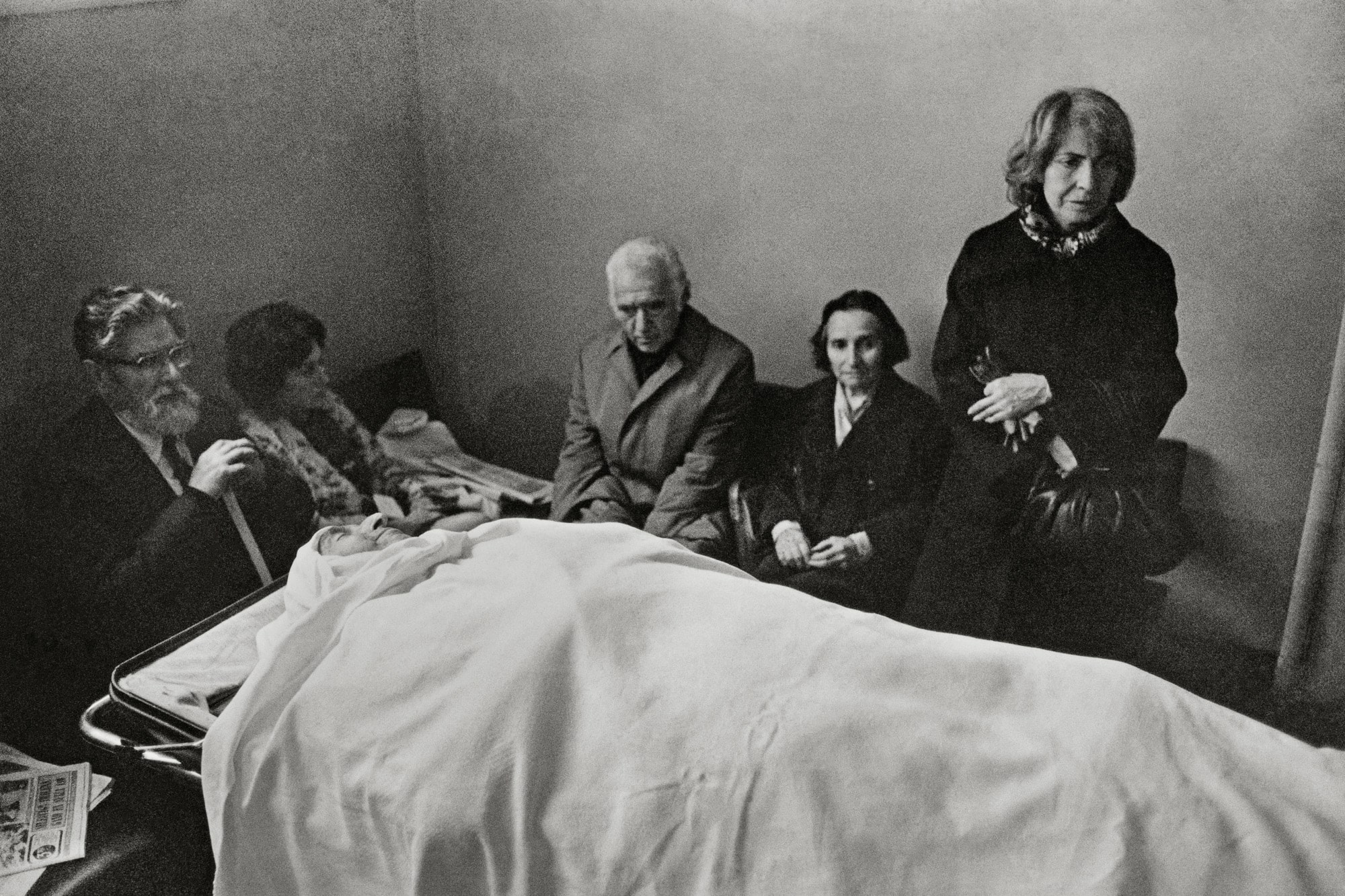

Also unpublished for a long time were the images that Teixeira captured of poet Pablo Neruda the day after his death at the Santa María clinic in Santiago. Thanks to the typical perseverance of a good photojournalist, Teixeira managed to be the only photographer who documented Neruda’s family next to his body before leaving the hospital. The day before, Teixeira received news that the poet was hospitalized and rushed to the clinic. He recalls that the clinic director quickly opened the door and allowed Teixeira to see the poet and his family, but he couldn’t take any photos.

On the night of Neruda’s death, Teixeira learned the news, and the following morning, he returned to the hospital. “I have to get in. I have to get in no matter what,” he said during the conversation. His persistence paid off: the photographer seized a moment of carelessness from an employee and managed to enter. Inside the clinic, after photographing Neruda’s body on a stretcher in a narrow hallway, he was able to introduce himself to Neruda’s widow, Matilde Urrutia, reminding her of the images he had taken of her and the poet years earlier in Bahia, during their visit to Brazilian writer Jorge Amado.

“Stay here,” Neruda’s widow is said to have told him, “your presence is significant at this moment.”

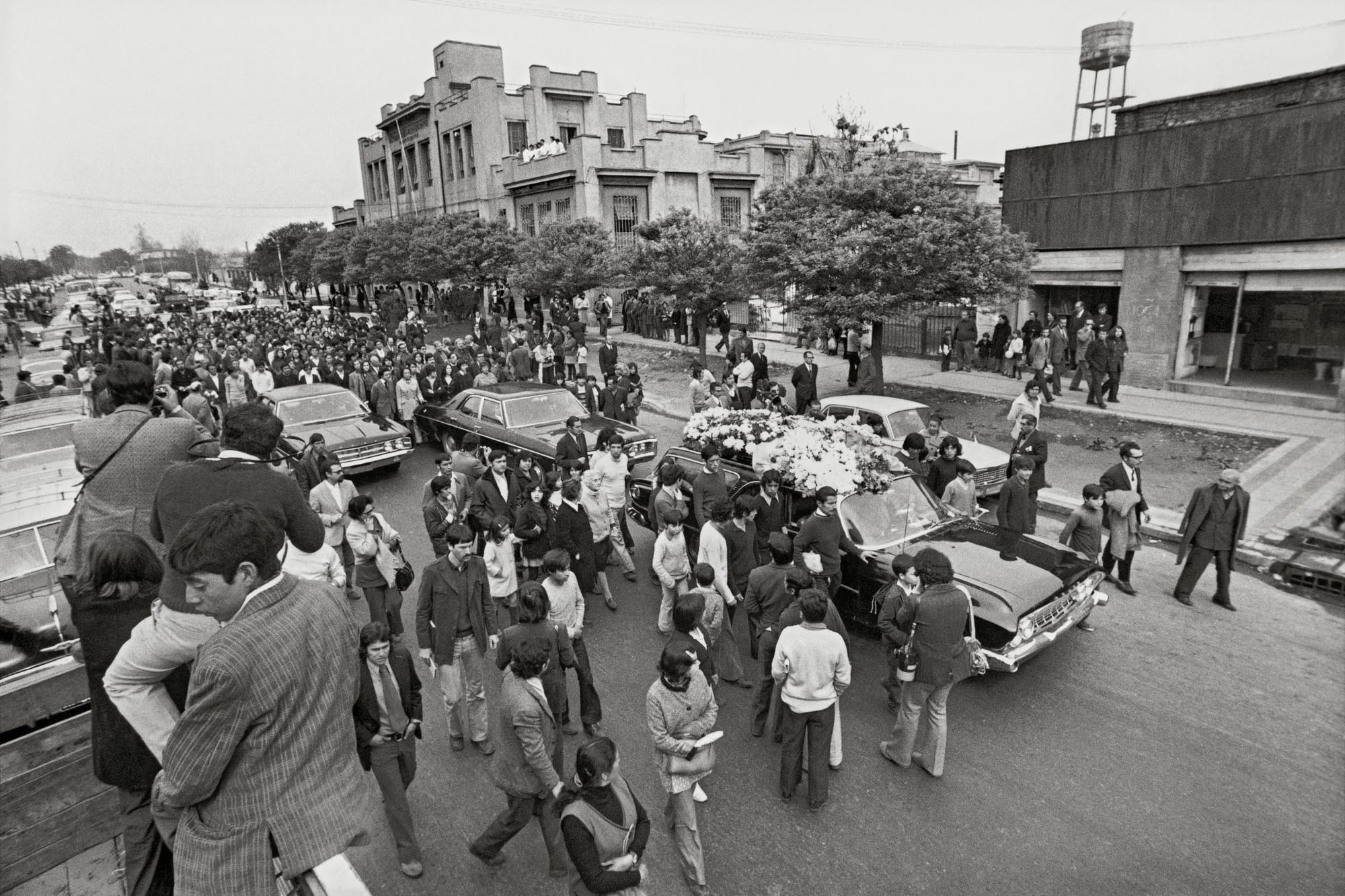

Teixeira was the only photographer who captured moments of the family in the clinic and accompanied Neruda’s body from there to his home, where he was laid in state. “We left, and there was no one in the streets. But then, as the hearse carried the coffin and we walked behind, people began to arrive, singing ‘The Internationale’ and shouting, ‘Neruda lives! Neruda is not dead!’ It was both emotional and sad. I felt the pain of seeing a Nobel Prize-winning poet, an international leader, being destroyed and killed by Pinochet’s madness.”

To reach the house, which the military had invaded and destroyed, they needed to cross a small stream in a forest. However, the soldiers had bombed a dam, turning the stream into a river. Teixeira recounts suggesting and helping to construct a makeshift bridge using doors and other pieces of wood to carry the coffin across.

Later, at the General Cemetery of Santiago, a multitude paid tribute to the poet, despite attempts at sabotage by the military junta. General Pinochet, who had barely made public appearances since the coup, called a press conference at the time of the burial, likely to draw the attention of journalists in the country.

“I told Pinochet to take a bath and continued accompanying Neruda in that incredible coverage, which was both sad and wonderful,” Teixeira recalls. “I sent the material to the newspaper, and I think one photo was published because everything was censored.”