Misses in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta

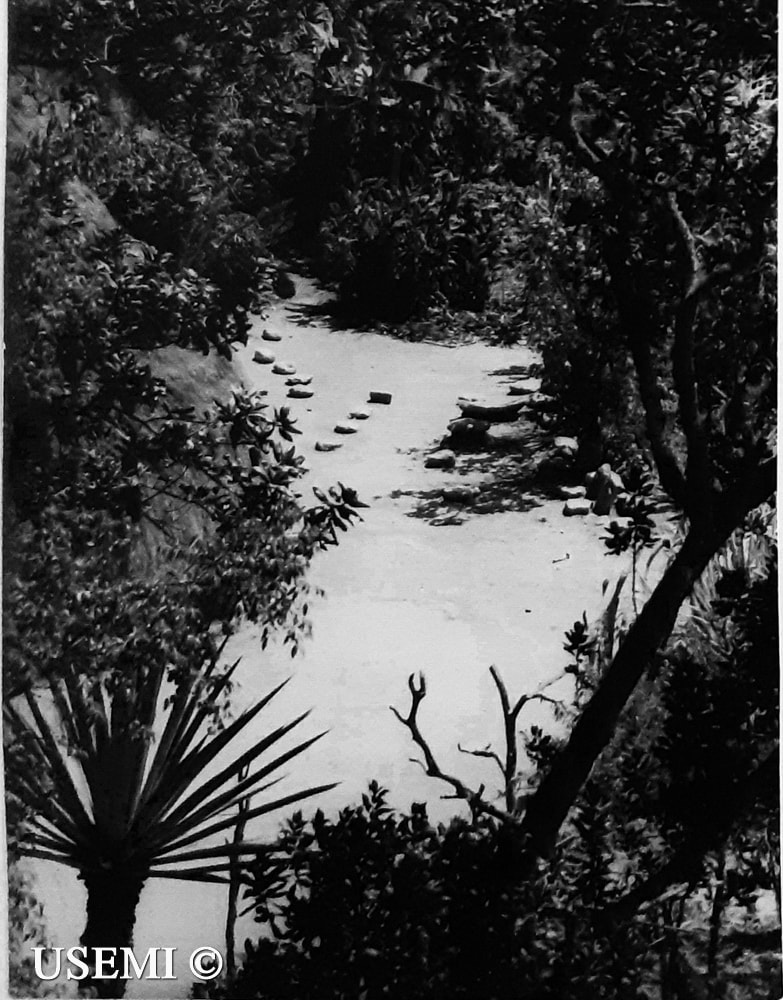

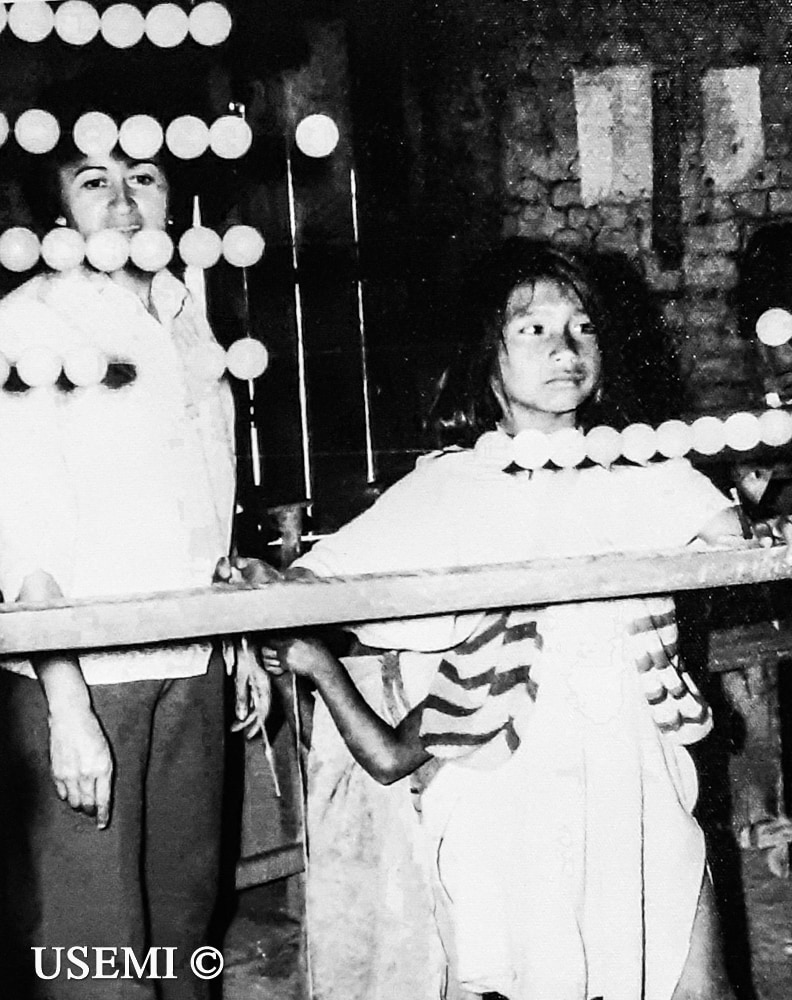

“From the 1960s to the 1980s, a diverse group of enthusiastic Señoritas, named after the Ikʉ (Arhuaco) and Kogi indigenous peoples, entered the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta and gave their lives to the social revolution: a revolution without weapons, but armed to the teeth of love, curiosity, and dreams. “

Juan Sebastián Zapata learned about the history of Las Señoritas, women belonging to the Secular Union of Missionaries (USEMI) in the middle of an anthropological investigation. The work that they carried out, although little known, was important: following the teachings of one of the founders of USEMI, Monsignor Gerardo Valencia Cano, and firm in the principles of the social doctrine of the church, they had a fundamental role in the organizational development of the Arhuaca community but also of the conservation of their customs, education, and health.

Juan Sebastián Zapata, sociologist and anthropologist, Daniela Rocha, clinical and legal psychologist, Santiago Dussan, artist, and Daniel Velásquez, filmmaker, came together to investigate and tell the story of Las Señoritas en la Sierra. At this moment they are in the post-production stage of a documentary feature film that aims to tell a good part of the story and make these women and their work visible. For all those who want to know a little more and support this initiative, the team launched a vaki.

How did you come to this story?

Juan Sebastián: I came to the Sierra in 2015 as a sociology intern with the Kankuamo indigenous organization and I was quickly delighted. The Kankuamo live on the southeastern slope of the Sierra and above them live some indigenous ikū (Arhuacos). For the master’s in anthropology, I decided to do a thesis on how this society is organized today. Investigating the social transformations, the influence of the Capuchin missionaries is evident, who made a thousand and one mistakes thinking that what they were doing was the best for the indigenous people.

So I learned that there was a very different mission: the Secular Union of Missionaries (USEMI) and I saw an interesting vein to investigate because it is also quite unknown. So we got together in an interdisciplinary team made up of Daniela Rocha, Santiago Dussan, Daniel Velásquez, and myself.

So what was this about the Secular Missionaries?

Daniela: USEMI was made up of missionaries who were educated by Monsignor Gerardo Valencia Cano, a bishop who worked in Buenaventura and was one of the founders of the Union. He relied on the social doctrine of the Church to work with the people. Thus, instead of seeking to “bring the word of God” to the territories, what he did was to recognize in poverty a series of Christian values that lead to self-giving. From that thought, he created a group that had missions around Latin America. A group of women arrived in the Sierra, invited by the Capuchins, who did not know who they were welcoming.

At the time there was an important peculiarity and that is that they were single women, but they were not nuns. It was a rare situation and that is why the communities began to call them Las Señoritas, the name we chose for the documentary. They lasted 20 years in the Sierra working with the indigenous people.

What kind of women were Las Señoritas? Who could be secular, single, and go on a mission to places like the Sierra?

Juan Sebastián: USEMI was made up of two very particular types of women: those from wealthy families with a Catholic ethic of service and women of popular origin who had an affinity with that missionary vision of dedication to the poor. Monsignor Valencia, they say, had clarity and what he did at the beginning was to target women from Catholic families who could economically afford to go to the jungle.

Daniela: We have found that a part of them came from important paisas families of the time. In an interview, it came out recently that Noél Olaya, one of the thinkers of USEMI, spoke to them about ‘Christian atheism’, something that we are understanding, but that referred to how to maintain the Christian values of dedication, but not necessarily a specific deity.

In other places, the Church, with its social doctrine, played an important role in supporting ethnic organizational processes. Did the Señoritas have a similar role in the Sierra?

Juan Sebastián: the first young lady who arrived in the Sierra did so as an Indigenous Affairs official and not as a lay missionary. She then started bringing USEMI. From this dual role, she was the interlocutor with the State. USEMI’s work with Incora for the delimitation of the Arhuaco Indigenous Reservation was fundamental. They were the bridge of communication.

You have told in your networks that you have a lot of information collected among that a large photographic archive. How have you thought about making the documentary?

Daniela: This documentary mixes the audiovisual, the anthropological, and the psychological. We collected 1200 photos from the USEMI archive, we have documents, letters, primers, books, as well as 45 cassettes with recordings of both important meetings with the government and with very important people, even nights of songs and guitar. We want to transport viewers back to that time while we narrate the reunion of the current ikū community with USEMI, because despite its importance there is a lot of silence around.

Finally, we want to show how this process of compiling the archive has been for us, interviewing Las Señoritas who still live, and indigenous people in the area. We want those three lines to come together in a big braid, allowing the viewer to be an active participant in the story.

Juan Sebastián: it has been difficult due to the amount of information we have. At that time and due to the distances, they communicated with letters, we have the intellectual production of 20 years of a large group of people. It was like his WhatsApp, they told things like “the jean I bought for Fulana was too big for her”, or “the bishop of Valledupar is telling us that what we do is guerrilla activity”.

Daniela: yes, at this moment we are refining the information, and we have discovered some points of tension, such as: being a woman and working in the Colombian reality of the 60s, also taking into account the indigenous culture; the whole thing about the political persecution and the way they had to come out. They encouraged the indigenous people to confront the Capuchins and seek to get them to leave the Sierra, but in the process, they also had to leave because they were missionaries.

For all those who want to support this project, the vaki is still open. Undoubtedly it is a deep investigation about a little-known part of history. Maybe it is due to the time, to the place where Las Señoritas acted, since they were women at a time when such a work would hardly be carried out.