When the WHO said that Covid-19 had pandemic status, governments around the world took different decisions: confinement, isolation, sectorized measures, intermittencies. The recommendations of the scientific world were also diverse and sometimes contradictory. There was only one thing that states, science and popular knowledge agreed with: you had to wash your hands. But: what about those who don’t have access to water? The Peruvian Mexican photographer Musuk Nolte asked.

That is how Historia del agua en el desierto (Story of the water in the desert) was born, a multimedia project that illustrates the water problem in the popular neighborhoods of Lima and the different solutions that arise between what the State provides, what the market decides and what the neighbors plan. The coverage was presented with photos of Musuk, journalistic texts by the Argentine journalist Gloria Ziegler and the design of Vera Lucía Jimenez. According to the study, more than 700 thousands people live without access to water service in Metropolitan Lima and El Callao.

In all these years, Musuk traveled around several countries and worked, especially, in the Amazon and the Andes. When the world was paralized by the pandemic, he asked himself some questions. “I think there is a global reflection, from the Brazilan or the American who travel to Singapore or Africa and in this context it wasn’t possible. We assume that we have to represent the other and this has been a kind of moment of self-criticism, of looking at where we are standing and what we are doing.”

So he looked around him and he realized that water (or rather, the lack of it) was a good way to talk about the real problems that run through the society to which he belongs. This work received the support of the COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Journalists and the Pulitzer Center and tells about the lack of tanker trucks, tanks with locks to prevent theft, contamination, health problems, homemade water pumps and the walks with heavy buckets. In the areas where he worked, he noted that “the virus was too abstract from the fact to get some water or food”.

How did you come to tell the story of water?

When the conjuncture of the pandemic happened, there was the uncertainty of what to do in the midst of the limitations. Normally, people had the idea that stories are far away, outside, that one has to travel. This was to start thinking around the environment where you live. I had to rethink what theme connected with what I was doing before, related to human rights, identity and the environment problems. Above all, thinking that I was interested in addressing the virus problem not from the conjunctural incidence (hospitals, confinement, masks) but thinking about what things are structural problems that propose me to trace a development of the project in which the incidence of the virus was the focus of interest but that it was a topic that could continue to develop in the following months.

I started from the conjunctural: the main thing that the government proposed was that you wash your hands for 20 seconds. Lima is a collapsed city in terms of the people it can receive, it has grown exponentially in the last 30 years and has grown towards extremes. Having been created on a desert, many communities have been settling in peripheral areas where there is no access to drinking water but there is no access to water naturally: a waterfall or a river. So I started asking myself that question: How do these people with very restricted access to water protect themselves from the virus?

Was it a reality that you knew before?

I knew the areas before because I worked in a newspaper for over four years and that let me visit the city almost in its totality and learn about the problems in Lima. I began with a concrete idea of working in a community, but through the process I realized that I needed to include a little more and in a more general way, so I asked myself how I could find two extreme opposite points of the city that can represent this problem. Santa Rosa (north) and Villa María del Triunfo (south). Those were places that I had visited for other themes, for example a report on tuberculosis, another on problems of housing access. It was shocking to see how fast they have grown in the last decade. Particularly the last year. It is a city that is growing, it is a critical issue, there are many more people than can be supplied.

Starting in the 50s, a more constant migration began to be seen, but between the 80s and 90s the bulk came, that large number of people mainly from the Andes, a little less from the Amazon, but also from the north and south coast. Today the city of Lima has a third of the national population.

How were they coping with the lack of water?

It is a problem that came before the pandemic. On one hand, there was the state’s measurements that were that families buy water from the tanker trucks. The water price fluctuated depending on the demand and supply. In the pandemic, they decided to provide it for free but they did not have enough tanker trucks and there was a lot of demand, so they had to hire some trucks.

Water tanks are placed on the roads, mostly made of dirt or sand, many of them unsuitable for storing water for human consumption. The lucky ones, can get a water pump and makevery poor connections to make to get it home. The vast majority carry it in buckets. This also brings a lot of other problems: for example, there is theft of water and even some tanks with padlocks. There are other contamination issues, so sometimes they let it settle for two or three days but it still brings stomach problems. Also, sometimes, the water becomes cloudy and is no longer drinkable. In Lima it hardly rains but it is a very humid city and there were some projects to trap the fog and thus be able to store that water, mainly to water the small gardens or wash clothes. Water is never wasted: after cooking it is always used for something else. Creativity is a means of survival.

Another great paradox is that, in the context of compulsory confinement, in the area that was “one more” of the problems and things they had to overcome, but it was not one of the main ones. The virus was too abstract compared to getting water and food.They are very impoverished families who live day by day and who have come to inhabit these territories out of necessity. Although there is also a serious problem of land trafficking, corruption, etc.

Another situation to highlight are the common pots that began to form a few weeks after the mandatory confinement, where what was had as food was gathered and cooked collectively to be able to resist the situation.

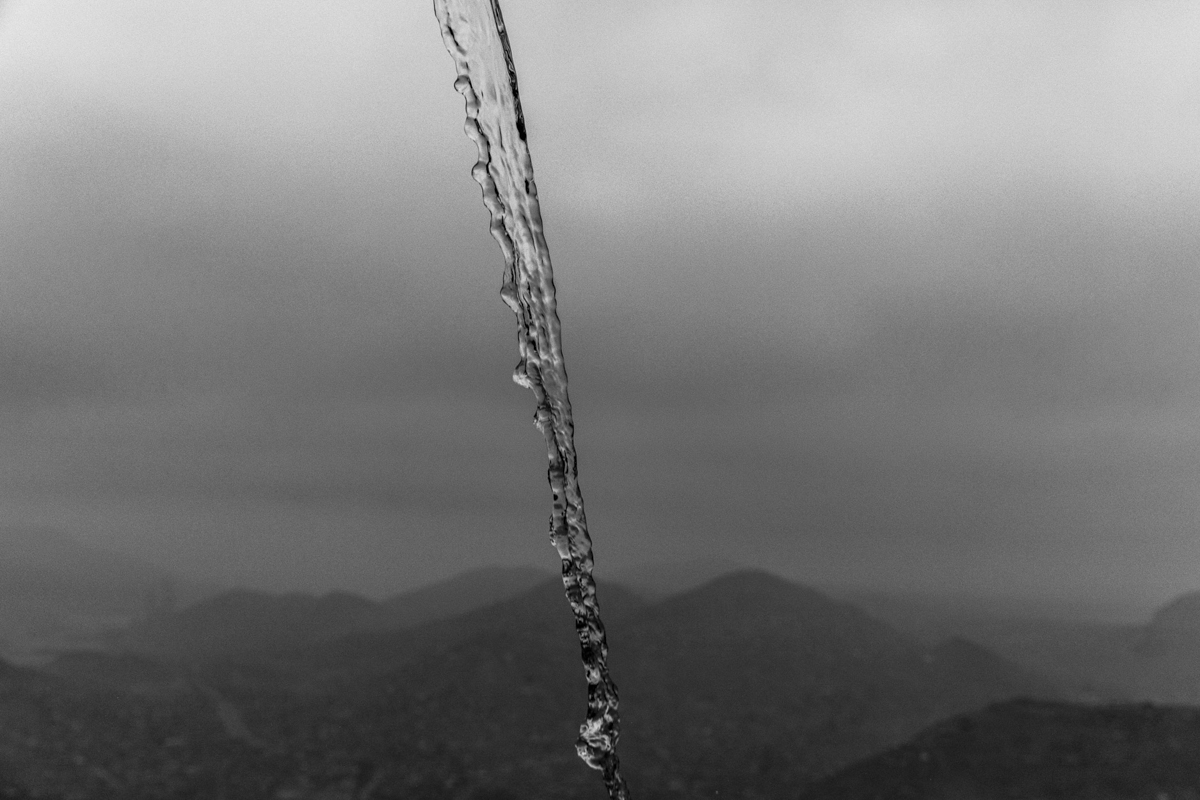

Why are the photos in black and white?

I feel there is a projection of that visual dialogue with what the content can say. Also there are images that were to be takena long time in different locations, and then I was interested in unify the work to concentrate on the situations. Sometimes the color distract the viewer. There are some images in which everything was dense, totally gray, as sometimes it is Lima when it is cloudy and there was not much difference between black and white and color. That was a paradox of using that language.

How did you choose and report the stories?

I worked with the journalist Gloria Ziegler, who is Argentine and resides in Perú. She had done a report about water. I was passing her the contacts that i was making, this was because we were trying to expose to the minimum who went but also to who welcome us. In the web, the written report is the common thread and the photos find a contact point. There is a structure that goes beyond the singular: we wanted to go in depth to try to provide information to portray how Lima is in that situation, how the water arrives, the difference in access that exists in areas closer to the city. capital or further away, the difference between what different families pay. There’s a more macro look at the water issue, and the pandemic issue comes in and out. The main axis is still water.

What continuities do you find in the different projects you have done?

In general, I think there is an interest in getting closer to working with communities, human groups organized for different reasons. In the background there is always a question in relation to how different social problems are carried out: human rights, equity or identity issues. In fact, the project in which I worked the longest is for families of the disappeared as a result of the internal conflict between the 1980s and 1990s, which is precisely what caused one of the great migrations to the capital. Not that there is a direct connection but, indirectly, everything somehow does.

Is the project finished or in progress?

In the first stage, as far as Lima and the pandemic are concerned, it is finished. To understand where the water comes from, you would have to go to the Andes and find the locations where it is born and see that route, how it encounters various pollution problems for various reasons, mainly due to mining. Working on that could make an interesting counterpoint. Sometimes one is not aware of how sensitive the connections are in nature and how what happens in the Amazon or in the Andes is ignored, without realizing that everything is connected and that sooner or later the effects will arrive.

Also thinking not in the moment of the pandemic but how the city is going to be reconfigured. Something that happened is that a few weeks after the state of emergency, many began to return to their home towns: the city ceased to be the promise it was. From one day to the next they were left without work and chose to return, where they had their mother’s house or a place to farm. I think the water issue is going to be key: the city continues to grow demographically. At some point there will not be resources for everyone and cities will reconfigure.

Musuk Nolte is 32 years old, was born in Mexico and grew up in Lima. He studied photography and specialized in contemporary photography at the Centro de la Imagen in Lima. He won several awards, such as the Eugene Courret and was awarded a scholarship by the National Fund for Culture and Arts (Fonca), the Master Class of the World Press Photo in Latin America and the Magnum Foundation, among others. He also published books: PIRUW (along with Leslie Searles they recorded Peruvian festivals, traditions and landscapes), Flor de Toé (along with Versus photo, a path to a parallel dimension in the jungle), Sombra de Isla (tells a side B of Cuba) and La resistencia del silencio (on political rhetoric), among others.